Abstract

This study examines the sovereignty claims of the Greek Cypriot Administration (GCA-Republic of Cyprus), Turkey and Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus as littoral states in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea regarding the delimitation of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and the Continental Shelf (CS). Although the GCA (as namely Republic of Cyprus) is a signatory of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), it has signed bilateral agreements with Egypt, Israel, and Lebanon. However, the GCA has neglected the existence of the frozen conflict in the island and is therefore faced with the reactions-challenges of Turkey and the TRNC after its decision to give licenses to MNCs and start the drilling process. Turkey and the TRNC have claimed their own sovereignty rights in regard to the Exclusive Economic Zone and Continental Shelf, which resulted in the agreements between TPAO (Turkish Energy Company) and the TRNC. Additionally, Turkey has started to conduct seismic surveys in the northern part of Cyprus and southern part of Turkey on the basis of the equal sharing principle. The lack of a comprehensive solution to the Cyprus problem is the basic source of the sovereignty dispute on the delimitation of EEZ and CS among Turkey, the TRNC and GCA, which is also reflected in the hydrocarbon surveys.

Keywords: Cyprus, Eastern Mediterranean, Exclusive Economic Zone, Continental Shelf, Energy

Introduction

The strategic and economic potential of the Eastern Mediterranean as well as its history makes it a source of contention for the countries in the region to delimit maritime zones which would shape the access to the discovered regional hydrocarbon resources. Conflicting political and legal claims are merging with old and new conflicts and have led to new geopolitical front in the Eastern Mediterranean where the disputes have grown to engulf not only Europe and the Middle East but also the Gulf, North Africa, and Russia at the same time. The unresolved Cyprus problem around the core issues of sovereignty, identity, and security as well as long-standing antagonism between Turkey and Greece are at the centre of the regional tension. However, Eastern Mediterranean crisis has gone beyond a bilateral regional crisis and transformed into a complicated international crisis in which the stakes are numerous including migration, disputed territories, competition for resources, law of the sea and power among many others. Considering sovereignty at the centre of the regional tension, this study aims at providing insights to understand how maritime jurisdiction areas can easily be a source of contention among states if natural resources are discovered in those maritime areas, and if the related parties have conflictual sovereignty claims over these areas. This fact can easily be observed in the hydrocarbon discoveries around Cyprus, which have instigated a political debate involving sovereignty implications. In this framework, different from the majority of other studies on this topic, this research aims to show that hydrocarbons are inseparable from the sovereignty context and the hydrocarbon debate is only a reflection of the sovereignty dispute between Turkey and Turkish Cypriots on the one hand, and Greek Cypriots on the other. In that sense, the natural gas discoveries around Cyprus have revealed the already existing disagreements among the related parties on the questions of sovereignty and sovereign rights to exploit those natural resources, which has ultimately resulted in the intensifying nationalistic rhetoric emanating from all parties. Basing on inseparability between international relations and international law in this issue; the first part of this paper provides a historical background and details on the emergence of problem. The second part shows the early signs of the Eastern Mediterranean crisis. The last part specifically discusses the positions of the GCA and Greece as well as the TRNC and Turkey in terms of the claims for a possible solution to the on-going crisis. Overall, it is important to acknowledge that under the unresolved sovereignty issue between the two communities, hydrocarbon discoveries in the disputed marine areas around the island of Cyprus would only intensify the current conflictual claims of the related parties on sovereignty and sovereign rights, both onshore and offshore.

Sovereignty

Sovereignty, as one of the core concepts of the international system, has been organised territorially for centuries and has provided states with the “right to territorial integrity and non-intervention in their internal affairs” (Krasner, 1988, p. 89). Referring to the supreme and absolute political authority of the states, it has also become critical for the protection of domestic order. Over time, sovereignty has changed due to the evolution of states different ways and at different rates (Nevers, 2015) and the relatively stable/constant interpretation of the concept with Westphalia has been challenged by the historical events of the 20th century. It has evolved as a way of resolving disputes over “ownership and control” (Caporaso, 2000). This fact is certainly true for the maritime areas of states, where the rights of ownership and sovereignty have merged to distinguish the economic sovereignty of the coastal state over resources located in the sea (Alah & Nezhad, 2017). Today, states are competing to expand their lands into marine territories and to be able to use different forms of sovereignty over those areas. In principle, the scope of sovereignty of the coastal states in maritime areas starts with a form of sovereignty that is similar to land territory and continues with the ownership and governance of economic resources under and beyond the continental shelf and EEZ (Alah & Nezhad, 2017, p. 1044).

Sovereignty in the sea has become extremely important in cases where the boundaries of the sea areas are disputed among littoral states as well as where such disputed areas contain hydrocarbon resources, as the international community has witnessed in the Eastern Mediterranean region in recent years. In this context, the debate about the hydrocarbon resources around the Cyprus issue essentially has a sovereignty dimension and has emerged due to the conflictual sovereignty claims of the related actors, i.e. Turkey, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), and the Greek Cypriot-run state, (which is internationally recognised as the Republic of Cyprus and will be hereafter referred to as the Greek Cypriot Administration (GCA)) and Greece over the overlapping sea areas. Under these conditions, state sovereignty in the sea areas is governed by 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which in most aspects is also considered as consistent with customary international law. In that sense, for states that are not party to the UNCLOS, customary international law would be the legal basis by which sea areas are regulated among the states.

As a sophisticated international treaty (Filis & Arcas, 2013), the UNCLOS codified some existing and already implemented rules and principles of customary international law; systemised rules of engagement that were previously based on the of nations (Çubukçuoğlu, 2014) and some new concepts have also been introduced. More specifically, it clearly defines the maritime areas of states and contains a legal regime that regulates the rights and duties of the states in terms of the use of their marine areas as well as their resources along with a binding procedure for resolving disputes among participant states. The scope of the rights and sovereignty of the littoral state depends on its clearly categorised maritime areas, i.e., internal waters, territorial sea, contiguous zones, archipelagic waters, exclusive economic zone, continental shelf, high seas, and international seabed areas. Among them, the EEZ and continental shelf will be the focus of the discussion in this research, considering the conflicting sovereignty claims made by the Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots over their EEZ and continental shelves as the main source of regional tension in the Mediterranean. Before examining in greater detail, it should be emphasised that the rights of the states regarding the EEZ and continental shelf are more restricted than those either in the territorial sea or in the contiguous zone. Both areas of a state can be accepted as “intermediate areas” that are not subject to the fullest sovereignty of the littoral state, which is given certain exclusive sovereign rights under the special regimes as stipulated in the UNCLOS (Gürel et al., 2013). Accordingly, the activities of all other states and/or non-state actors are dependent on the clear consent of the coastal state.

The EEZ is defined by the UNCLOS. Article 57 of the Convention defines the EEZ as an area “… beyond and adjacent to the territorial sea … which shall not extend beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured.” The EEZ of a littoral state is coextensive with its continental shelf for up to 200 miles. Since the EEZ is not considered to naturally exist from the beginning, it has to be explicitly proclaimed by the coastal state. Upon proclamation, the EEZ enables the littoral state to exercise its sovereign right of “economic exploitation and exploration of the zone”, the seabed and its sub-soil, in terms of both “living and non-living resources” as well as jurisdiction over offshore platforms and activities, including artificial islands, marine fisheries and scientific research (UNCLOS, Article 56).

On the other hand, the continental shelf is “the seabed and subsoil of the submarine areas that extend beyond its territorial sea throughout the natural prolongation of its land territory to the outer edge of the continental margin, or to a distance of 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured where the outer edge of the continental margin does not extend up to that distance” (UNCLOS, Article 76/1). The Convention enables the coastal state to exercise its absolute sovereignty over the exploration of the continental shelf and exploitation of “all natural resources … [which] consist of the mineral and other non-living resources of the seabed and subsoil…” (UNCLOS, Article 77). Different from the EEZ, all coastal states have and sovereign rights over their continental shelf, which is a natural right of existence for the state from the outset and does not depend on the express proclamation of the coastal state.

Although this appears to be a technical issue, delimiting maritime zones is also a political process involving legal, political, technical, historical, environmental and economic dimensions. It could become particularly problematic if the opposite coasts of states are less than 400 nm apart from each other, as is the case in the Mediterranean, and if the coastal states lack any pre-existing agreement. The problem becomes even more complicated if the opposite states have conflictual sovereignty claims over the same maritime areas, which is the core of the problem related to the hydrocarbon discoveries around Cyprus. Principally, under normal conditions, Article 74 and 83 of the UNCLOS govern the delimitation process in terms of the EEZ and continental shelf, respectively. Both articles urge the coastal states to settle on delimitation through a mutual agreement on the basis of international law in order to achieve equitable solutions. Where an agreement cannot be reached in a reasonable period of time, states are required to resort to dispute settlement procedures indicated in Part XV of the Convention. Part XV (UNCLOS, Articles between 279-299) promotes collaborative approaches for the peaceful settlement of disputes among parties before the decision is made to take the issue to forums such as the International Tribunal on the LOS, the ICJ or an arbitration panel to achieve a binding resolution (Filis & Leal-Arcas, 2013). In practice, however, the developments are far from the ideal expectations, as discussed in this study. Before them, the following part summarises Cyprus problem from a historical perspective as the basis of the current sovereignty conflicts.

Emergence of sovereignty allegations of the GCA under the shadow of the Cyprus Problem

As a small island located in the Mediterranean Sea, Cyprus gained its independence from the United Kingdom in 1960 and it subsequently became a republic on the basis of its multicultural structure.

The Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot Communities became the founders of the republic, whereas the Maronites, Armenians and Latins became the minority groups in the Republic of Cyprus according to the constitution of 1960. The republic was established on the basis of a multicultural and functional federative structure. However, the struggle for power among the communities emerged in 1963 with the attempts of Makarios to make amendments to the constitution, which were resisted by the Turkish Cypriot who claimed that they were against the nature of the republic. Therefore, intercommunal conflicts started in the autumn of 1963. As a result, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) adopted resolution 186 and deployed its forces under the name of the United Nations Peacekeeping Forces in Cyprus (UNFICYP) (United Nations Security Council Resolution 186, 1964). On the other hand, the Turkish Cypriot leadership left the government as well as the legislation organ as they perceived their lives to be in danger. Consequently, the Greek Cypriots assumed the sole leadership of the Republic of Cyprus after 1964. However, Greek Cypriot nationalists were not satisfied, and Nikos Sampson attempted a Coup d’état against Makarios’ government with the aim of unifying the island with Greece, which ultimately resulted in the Intervention of Turkey on the basis of the Treaty of Guarantee. Therefore, the island has since been divided into two parts and the Turkish Cypriot leadership declared the Turkish Federative State of Cyprus in 1975 for the creation of the Federal Cyprus State. Following that, high level agreements were signed between Denktas-Makarios and between Denktas and Kyprianou (1977-79). These high-level agreements articulated the bi-communal, bi-zonal federation on the island. However, the disputing parties could not reach a solution for the island during this time. Therefore, Denktas declared the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) in 1983. The newly founded TRNC was only recognized by Turkey and the UNSC adopted resolution 541, calling on its member states to declare that the TRNC was not legal and that they should not recognize any Cypriot State other than the Republic of Cyprus (United Nations Security Council Resolution 541, 1983)

The disputing parties came close to a solution with the Annan Plan in 2004, although the Greek Cypriot Community refused the plan offered in the referendum and the Greek Cypriot leadership succeeded in gaining full EU membership. The northern part of the island continued as a state in which the has been suspended and where the EU does not have any sovereignty.

Ultimately, the status quo has continued in Cyprus since 1974, and the situation can be defined as a frozen conflict and unsolved problem; however, this situation has led to the emergence of new problems among the relevant parties, namely Greece, Greek Cypriots, Turkey and Turkish Cypriots, with the discovery of potential new energy sources and energy routes in the Mediterranean Basin.

The GCA has specifically focused on energy issues since the beginning of the 2000s due to the increasing natural gas resources and consumption of Egypt in its coastline. In addition, the positive results generated by seismic research conducted by Israel in the Levant basin represent another factor that pushed the Greek Cypriot authorities to explore the potential hydrocarbon resources in the region. Eventually, Greek Cypriot authorities dedicated themselves to establishing the legal framework according to the international law with reference to the UNCLOS. Therefore, the Greek Cypriot authorities were increasingly motivated to search for hydrocarbon resources, which directly led to the emergence of the issue of delimiting maritime jurisdiction areas in the Mediterranean Sea, which is an important and delicate issue for several reasons, including economic, political, geo-strategic and energy resources. Under those conditions, delimitation of the Exclusive Economic Zone and continental shelf as well as sovereignty proclaims over the hydrocarbon sources in the Mediterranean Basin have emerged as the new problem of the communities and the guarantor states in the Mediterranean Basin as well as Egypt and Israel. Therefore, the Mediterranean Sea has witnessed an increase in the activity of coastal states who have the objective of extending their powers seaward.

Sovereignty conflicts among the littoral states in the Mediterranean represent one of the direct results of the disagreements on the delimitation of maritime jurisdiction areas, i.e., the EEZ and the continental shelf. Both the EEZ and continental shelf are crucial concepts of modern international maritime law. The UNCLOS defines guidelines for the responsibilities and rights of the states in their use of seas and establishes a rule of conduct over all maritime disputes between signatory parties. Despite the well written and clearly expressed rules of the UNCLOS regarding the delimitation of maritime zones, the crux of the problem is that Turkey, Greece, the TRNC and GCA are unlikely to agree on their interpretation of the convention regarding the EEZ and continental shelf delimitation in the Mediterranean. Moreover, the complexity of the Mediterranean geography leads to the overlapping of maritime jurisdictions among the coastal states with unending conflicts and instability in the region (Ece, 2017). Turkey’s non-party status to the UNCLOS, the lack of international recognition of the TRNC and the lack of diplomatic relations between Turkey and the GCA also aggravate the already existing problems.

Early signs of the accelerating crisis in the Eastern Mediterranean

Early signs of the Eastern Mediterranean crisis appeared as the result of a number of specific policies implemented in the GCA in cooperation with Greece. The reactions of Turkey and TRNC against them, as discussed towards the end of this part, have complicated existing conditions regarding the regional balance.

The maritime agreements of GCA in the Mediterranean

As an early initiative, the GCA focused on signing delimitation agreements with a number of littoral states. The first EEZ Delimitation Agreement was signed between Egypt and the Greek Cypriot Administration on 17th February 2003. With this agreement, both sides agreed on strengthening good neighbourhood relations referring to the UNCLOS of December 1982. According to this agreement, the parties agreed on a median line (Geneva Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone, Article 12, 1958) which is equidistant from the baseline of each state (Agreement between the Republic of Cyprus and the Arab Republic of Egypt on the Delimitation of the Exclusive Economic Zone, 2003). The median line and its limits are clearly defined, and the coordinates are indicated in the annexes of the agreement (Agreement between the Republic of Cyprus and the Arab Republic of Egypt on the Delimitation of the Exclusive Economic Zone, 2003. The most important article of the agreement is Article 2, which enforces the cooperation among the parties if the natural resources of one state extend into the EEZ of the other state (Agreement between the Republic of Cyprus and the Arab Republic of Egypt on the Delimitation of the Exclusive Economic Zone, 2003; see also Figure 1.1). Another significant dimension of the agreement is that it gives consent to arbitration if the parties are unable to find a solution in cases of dispute.

Source: http://www.marineregions.org/documents/I-44649-map.pdf

The GCA also signed similar agreements with Lebanon and Israel. After the rejection of the UN Annan Plan for the reunification of the island by the Greek Cypriot Community, the Greek Cypriot leadership succeeded in joining the EU with the name of the RoC, Although Turkish Cypriots accepted the Annan Plan, the acquis communautaire has been suspended in the northern part of the island. Therefore, the Greek Cypriot leadership has begun to exploit the international recognition it is afforded by membership of the EU. In particular, it has focused on rapprochement with Lebanon and Israel to determine its EEZ and has strengthened its sovereignty claims in the Mediterranean Sea. Hence, the GCA signed an agreement with Lebanon in 2007 for delimitation of the EEZ. However, the agreement has not been ratified by the parliament of Lebanon due to the close relations of Lebanon with Turkey, meaning that the agreement has yet to be implemented.

The Greek Cypriot leadership perceives the disputes among Israel and Turkey as an opportunity for rapprochement with Israel, because it has maintained a close relationship with the Arab world since the independence of Cyprus and at the Non-Alignment Movement rather than Israel. The improvement of diplomatic relations between the GCA and Israel was reflected on their agreement to share sovereignty and for delimitation of the EEZ in the Mediterranean Sea.

Eventually the parties agreed on the delimitation of EEZ and signed the agreement on 17th December 2010. The agreement contained five basic articles and annexes. The agreement clearly determined the geographical coordinates of the median line and limits among the two states (Agreement Between the government of the State of Israel and the Republic of Cyprus, on Delimitation of the Exclusive Economic Zone, 2010). The EEZ was determined with 12 coordinates ((Agreement Between the government of the State of Israel and the Republic of Cyprus, on Delimitation of the Exclusive Economic Zone, 2010), and the parties agreed to cooperate in the Mediterranean Basin and if any disputes emerged, their priorities would be to commence arbitration (see Figure 1.2).

The agreement was ratified in 2011, and the implications of the agreement are not only related with the economic exploitation of the Mediterranean Basin, but also the geopolitical and strategical priorities of Israel and GCA against Turkey (Israel-Turkey relations has strained since 2009 and then it became a catalayzer for rapprochement among Cyprus-Israel).

Although Greek Cypriot officials and the officials of other littoral states referred to the UNCLOS, they solved the EEZ problem with bilateral agreements, which are used more frequently by neighbouring littoral states for offshore zones. Therefore, they share the sovereignty among themselves in related offshore areas. Meanwhile, the GCA and Greece neglected the positions of Turkey and the Turkish Cypriots in their efforts. This fact shows that as opposed to the UN requirements, the GCA has excluded Turkey and Turkish Cypriots in the Mediterranean even if they are also among the littoral states. The solution of the issue in bilateral level, however, conflicts with Articles 59, 74 and 83 of UNCLOS all of which encourage the coastal states (also as stated in the previous parts) to resolve the delimitation conflicts “on the basis of equity and in the light of all the relevant circumstances, taking into account the respective importance of the interests involved to the parties as well as to the international community as a whole”. However, any bilateral agreement excluding Turkey and TRNC as the parties to the conflict violates the equity principle envisaged in the above mentioned articles of the UNCLOS.

Internationalisation of regional drilling

The positive results of the drilling conducted by Egypt and Israel encouraged the Greek Cypriot authorities to deal with the hydrocarbon issues more seriously. Therefore, the Greek Cypriot Council of Ministers decided to establish the Cyprus Hydrocarbons Company (CHC) as a national company in 2007 (Legal Status”, Cyprus Hydrocarbons Company, 2019a). However, the process of establishing this company was not completed until 2014. The main tasks of the company were defined as the management of the reserves in the EEZ of the GCA and facilitating the sharing of these reserves, maintaining ownership interests in a potential LNG terminal, and marketing the resources of Cyprus to maximize the interests of the country (Legal Status”, Cyprus Hydrocarbons Company, 2019a).

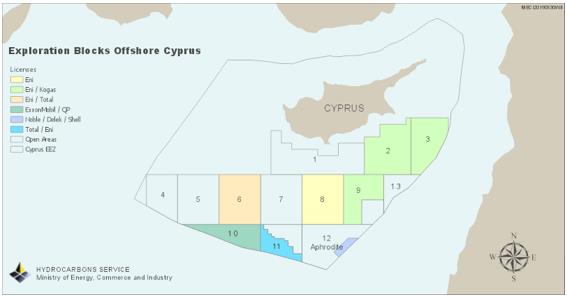

The Greek Cypriot authorities issued the first license in 2007 and then defined their offshore blocks located in the south eastern part of the island (see Figure 1.3). Afterwards, they awarded hydrocarbon exploration licenses to Noble Energy International LTD in 2008 (Cyprus Hydrocarbons Company, 2019b). The attempts of the GCA indicated that the Greek Cypriot authorities attempted to clear up the EEZ boundaries and expand it by focusing on bilateral agreements with the littoral states, i.e., Egypt, Lebanon and Israel. However, they did not consider the existence and rights of Turkish Cypriots as a partner of the island. Rather, they internationalised the issue as will be discussed in the following part.

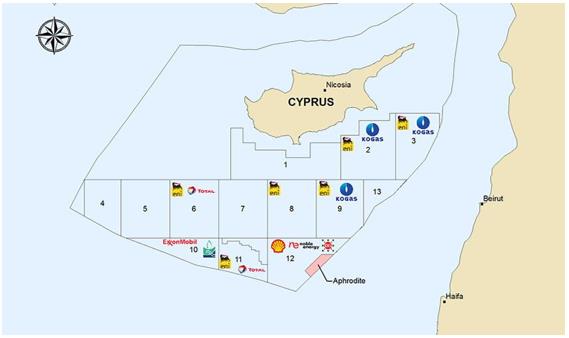

As a result, Noble Energy International started drilling in Block 12 and the first tangible results emerged in 2011. According to these results, Noble discovered almost 5-8 tcf (trillion cubic feet) of natural gas resources (Cyprus Hydrocarbons Company, 2019b). Subsequently, the Greek Cypriot authorities gave a second license to Noble to conduct exploration drilling in block 12 (Cyprus Hydrocarbons Company, 2019b; see Figure1.4). In spite of the appeals made by the Turkish Cypriot leadership to the UN institutions, the Greek Cypriot authorities have continued to license international companies and made them partners of the hydrocarbon resources of Cyprus. For instance, Total was awarded Blocks 10-11, the Delek group has cooperated with Noble in Aphrodite and confirmed reserves of 3.6-6 tcf. ENI International has started work with Total in Block 6 and Block 8, while ENI International has also cooperated with the Korea Gas Cooperation (KOGAS) and are working together in Blocks 2, 3, and 9 (Cyprus Hydrocarbons Company, 2019b). Additionally, Exxon Mobile and Qatar Petroleum started work in Block 10 in 2017 (Cyprus Hydrocarbons Company, 2019c).

East Med as “a new imagined project” and challenge to Turkey and Russia

The Eastern Mediterranean (EastMed) pipeline project has been supported by the EU Commission since 2015, and it is clearly stated that the project aims to develop the indigenous gas resources of the EU (IGI Poseidon, 2019). The project incorporates 1300 km of offshore and 600 km of onshore pipeline with the objective of delivering 10 Bcm (billion cubic meters) of gas per year (IGI Poseidon, 2019).. Although the project is represented as viable, it may be interpreted as costly when compared with the routes of Turkey, because it is clear that less offshore pipeline is required and less costs will be incurred based on the geographic features. On the other hand, Charles Ellinas (2018), writer for the Cyprus Mail, has argued that the project is doubtful, because 10 BCM billion cubic meters of gas can provide only 2 percent of the total European gas consumption.

Cyprus, Greece, Israel and Italy signed a memorandum for the construction of the gas pipeline from the offshore zones of Israel and Cyprus to Europe, where gas reserves were discovered in December, 2017 (Geropoulos, 2017).

The EastMed project was officially signed in December 2018 by Nicos Anastasiadis, the leader of the Greek Cypriot Administration, as well as Alexis Tsipras and Benjamin Netanyahu, Prime Ministers of Greece and Israel in Beersheba, Israel (Energy World Digital, 2019). Afterwards, these three leaders met again in Jerusalem on 20th March 2019 with the attendance of Mike Pompeo, US Secretary of State (Energy World Digital, 2019). Mike Pompeo underlined that the USA provided full support to the cooperation of Greece, Israel and Cyprus in the region and he brought attention to the prosperity and security in the region by highlighting the expansionist tendencies of Iran, China and Russia in the Middle East and West.

The EastMed project can be clearly evaluated as a challenge to Russia, China and Iran in terms of political and economic issues.

EastMed pipeline project is a challenge to Turkey. Considering it bypasses Turkey and excludes Turkish territory in its route to deliver gas from the Eastern Mediterranean to Europe, Turkey has been the leading actor to oppose it. Turkey sees the EastMEd project “as a tool for Turkey’s exclusion”.

The European Union estimates that the initial cost of the pipeline will be 7 billion Euros and then the companies will provide the necessary funds to finance the project (Tzanetakou, 2019). Facing with this cost and doubts about the economic feasibility of the EastMed project, it is not clear whether the project will be economically viable (see Figure 1.5). What has become clear is that the interest in the EuroMed project is based more on diplomatic and geopolitical reasons than on its economic feasibility. In addition, the project has also become a geopolitical challenge of the Euro Atlantic policies in the region, which are attempting to challenge the sovereignty claims of Turkey and the TRNC in the Mediterranean Basin.

Ultimately, the Greek Cypriot Administration is attempting to maximize its role in the Mediterranean Basin by taking endorsements from Egypt and Israel. The surveys do not clearly illustrate whether the hydrocarbon reserves are efficient or not; however, it is clear that there are sovereignty disputes among all littoral countries. Additional to this, Turkey’s initiative has challenged to this project by signing the memorandum of understanding with Libya regarding the EEZ in autumn of 2019, which enlarges the EEZ of Turkey and Libya in where the EastMed project was assumed to pass (Strategic Step the Eastern Mediterranean Equation: Memorandum of Understanding Between Turkey and Libya, Presidency of the Republic of Turkey, Directorate of communications, 2020).

However, recently Russian military operation in Ukraine and following this, emergence of tension between members of NATO and Russia reasoned to push western states to seek new alternative energy sources. According to this, Victoria Nuland, US Under Secretary of State, has toldjournal that there is no time and money to construct the EastMEd project and she pointed that Turkey should cooperate with Greeece, Israel, Egypt and Cyprus to transfer natural gas via LNG (Euractiv, 8th April 2022).

Therefore, Nuland has declared death of the project and encouraged new arrangements by including Turkey to end up dependency of Europe on Russian natural gas resources.

Reactions of Turkey and TRNC

Under the current political conditions on the island, Turkey and the Turkish Cypriot authorities have been raising their objections to the actions of the Greek Cypriots concerning the EEZ delimitation and offshore exploration on two basic grounds: the delimitation issue itself and the protection of the rights of Turkish Cypriots. Regarding the former, Turkey has defined the outer limits of its continental shelf in the Eastern Mediterranean as the west longitude of 32° 16' 18" E following the “median line between Turkish and Egyptian coastlines” (Note No. 2004/Turkuno DT/4739, 2004). In addition, by referring to the UN, Turkey has also registered its and sovereign legal rights and legitimate interests in this area arising from the confirmed principles of international law.

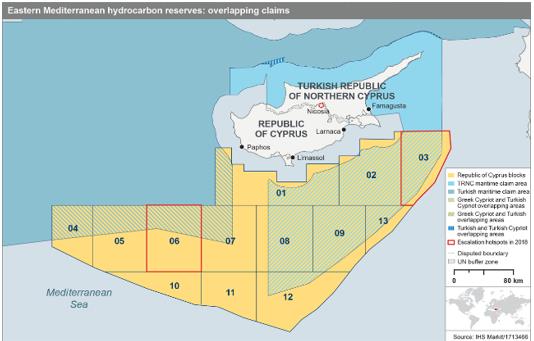

Referring to its declaration, Turkey argues that the EEZ that the GCA has claimed in the west almost completely clashes with Turkey’s continental shelf, and there is a partial overlap with the exploration Blocks numbered 1, 4, 5, 6 and 7 in the southwest (see, Figure 1.6). Additionally, other areas claimed by the GCA in the south fall within the jurisdiction of the TRNC according to the agreement on continental shelf on which Turkey and the TRNC put their signatures in September 2011. Therefore, Turkey has objected to and does not recognise the 2003 Delimitation Agreement between Cyprus and Egypt due to the fact that it ignores Turkey’s continental shelf rights in the region. Instead, Turkey authorised its national oil company, TPAO, to proceed with exploration of its registered continental shelf and provided a license and oil exploration permission to TPAO in the Official Gazette on 9 August 2007. From the perspective of international law, this was a tacit declaration of Turkey to the international community that it has continental shelf rights in these specified regions (Başeren, 2010). In other words, this is a disputed area in which Turkey is committed to protecting its sovereign rights based on international law and will not allow any unauthorised oil/gas exploration and exploitation activities by any other state or entity on its continental shelf (U.N. Doc. A/71/875-S/2017/321). Turkey has always been prepared to defend its national interests and rights against other states.

Turkey and the TRNC also oppose the actions of the GCA in terms of hydrocarbon developments and the delimitation issue on the basis of the sovereignty issue of the broader Cyprus problem with an emphasis on the rights of Turkish Cypriots in Cyprus’ maritime areas. In this regard, Greek Cypriots are neither legitimately nor morally competent to represent or to act on behalf of the Turkish Cypriots or the whole island. This extends to the signing of bilateral treaties by the GCA with the countries of the region, particularly those related to sovereignty including the delimitation of the maritime jurisdiction areas and conduct of gas/oil exploitation in the Eastern Mediterranean before a comprehensive settlement of the Cyprus issue has been achieved (U.N. Doc. A/61/727-S2007/54; U.N. Doc. A/68/902). All these actions reflect the exercise of sovereignty at the international level, which should have been jointly enjoyed by the Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots owing to their status as equal co-founding partners in the 1960 Republic of Cyprus. As was clearly expressed by the then President Mehmet Ali Talat, the Greek Cypriot side “represents exclusively the Greek Cypriot people and does not have any authority to negotiate and conclude agreements, conduct exploratory surveys, pass legislation or grant exploratory rights or exploitation licences on behalf of Cyprus as a whole” (U.N. Doc. 2009/216). Since they are equal constituent communities in the island, they have equal rights and say over the exploration for and development of all natural resources and maritime areas of the island of Cyprus. From this perspective, any unilateral action of the GCA and their attempts for delimitation of maritime jurisdiction areas in the Eastern Mediterranean and for the exploration of the regional oil and natural gas deposits are aimed at creating a in the region, which is totally unacceptable for Turkish Cypriots (U.N. Doc. A/61/1027-S2007/487). In that sense, along with the legal claims of Turkey, the TRNC has inalienable and inherent rights in the Mediterranean where any delimitation exercise must take the legal rights and legitimate interests of Turkey as well as the TRNC into consideration (Press Statement, 2011; Kaya 2019). Under the current conditions, two independent self-governing administrations exist in Cyprus, where each of them is exercising sovereignty and jurisdiction in its respective territories and each side represents itself (U.N. Doc. A/73/827-S/2019/297). Therefore, any unilateral act by the GCA specified above, and specifically the Delimited Agreement signed with Egypt, is “null and void and is not, in any way, binding on the Turkish Cypriot people or the island as a whole” (U.N. Doc. A/61/727-S2007/54).

In line with Turkey’s official statements and in response to the bilateral agreements of GCA with the third countries and to their exploratory drilling off the southern coast of the island, both Turkey and the TRNC have raised objections to the agreements that the GCA signed with Egypt, Lebanon and Israel and registered their objections with the UN. They also collaborated to take “reciprocal steps of equal significance” with the objective of restoring political balance in the region (Gürel & Le Cornu, 2013, p. 14). Turkey and the TRNC signed the “Continental Shelf Delimitation Agreement” on 21 September 2011. As Mehmet Dânâ, the then Representative of the TRNC, clearly stated in the Official Letter of TRNC sent to the Secretary General of the United Nations on 30 May 2014 This agreement was signed as a “preventive measure aimed at dissuading the Greek Cypriot side from creating any fait accompli in the region” (U.N. Doc. 68/902) and draws the line as the boundary between the southern coast of Turkey and northern coast of Cyprus on the basis of equitable principles and within the limits of international law as opposed to the median/equidistance line. At the same time, the TRNC issued hydrocarbon exploration licences to TPAO in seven blocks in the north, south and east of Cyprus called zones A, B, C, D, E, F and G. The last two clash with the exploration blocks 1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 12 and 13 of the GCA (Map 1). The delimitation agreement was followed by the signed between the Ministry of Economy and Energy of the TRNC and TPAO in November 2011. The contract authorised the latter to commence seismic research and hydrocarbon exploration as well as to drill and operate wells in the relevant blocks. Since then, Turkey has been active in the Mediterranean in its efforts to protect historical rights of Turkish Cypriots regarding hydrocarbon resources around Cyprus. Turkey conducts its seismic research activities in the Eastern Mediterranean mostly by its seismic research vessel mapping for potential future oil and gas resources in the disputed waters. Even the most recent NAVTEX of Turkey issued in December 2020 authorised it to carry out seismic studies (along with two other vessels, the and) until June 2021. These attempts of Turkey and the TRNC are, on the one hand, important in terms of strengthening the claims of the Turkish Cypriots that they have the right to an equal share with the Greek Cypriots regarding the hydrocarbon exploration and maritime jurisdiction. On the other hand, the clash between the seven exploration blocks of the TRNC in its EEZ and the GCA’s unilaterally delimited Blocks 2, 3, 8, 9, 12, 13 has complicated the already fragile conditions among the parties in the region.

Arguments of Greece/GCA and Turkey/TRNC for a viable solution in the Eastern Mediterranean

Since this study argues that a solution to the long-lasting Cyprus problem is the root of the current sovereignty conflicts in the Eastern Mediterranean, it is crucial to represent the perspectives/positions of both sides for a viable solution.

Perspectives of Greek Cypriot leadership and Greece

The Greek Cypriot Administration and Greece have always underlined the importance of the sovereignty of Cyprus and they refer to the 1982-UNCLOS, which was signed by the Greek Cypriot Administration in 1988 and entered into force in 1994 (Iperkiyou Ekseterikon Kypros, 2019). Greek Cypriots have tried to use their international recognition advantage and have underlined the importance of UNCLOS, which has not been signed by Turkey. Also, the Greek Cypriot Administration does attach any importance to the policies and treaties of the TRNC with Turkey due to the lack of full international recognition of the TRNC and accuses Turkey of conducting activities in the Mediterranean Sea that violate the sovereign rights of Cyprus. However, it is clear that such problems are generally solved by diplomatic means as can be observed in the historical international relations. Disputing parties generally try to use negotiation or arbitration or the International Court of Justice to solve their problems.

The Greek Cypriot leadership has always acted alone on the hydrocarbon issue and on the determination of EEZ and Continental Shelf of the island without taking the Turkish Cypriots into consideration. The position of the Greek Cypriot leadership is clear that they are not concerned about the vulnerabilities of the Turkish Cypriots when signing international treaties-agreements. This fact was exemplified in 2008, when Demetris Christofias became president of the RoC. This led to significant expectations across the island, because Christofias was perceived as a pro-solution leader. However, he did not change the approach of the Greek Cypriots regarding the energy issue during his presidency. Although Talat and Christofias agreed to establish technical committees and confirmed a comprehensive solution in Cyprus would be established on the basis of a bi-zonal and bi-communal federation, the Greek Cypriot authorities still granted Noble Energy International LTD an exploration licence for Block 12 (Özgür, 2017). This process clearly indicates that that the Greek Cypriot authorities do not care about the vulnerabilities of Turkish Cypriots with regard to drilling; however, they merely state that they will work for the benefits of both communities in regard to the hydrocarbon issue, as Christofias stated at the UN General Assembly, where he also underlined that revenues of the hydrocarbons would be shared by the constituent states (Statement of Demetris Christofias, 2011). Mehmet Ali Talat, (President of the TRNC, 2005-2010, supports re-unification of the island and worked for ‘’Yes’’ Annan Plan) pointed that ‘’Greek Cypriot leadership has always a conservative position and does not want to share the sovereignty with Turkish Cypriots, we may say similar things for Christofias as well (Interview with Mehmet Ali Talat, March, 2021). Talat has also argued that Christofias has come to a more moderate position at the end relatively with other Greek Cypriot leaders, however it was not enough (Interview with Mehmet Ali Talat, March, 2021).

Stefanos Stefanou, spokesman for the Greek Cypriot government also stated that “our sovereign right is not negotiable”, which referred to the position of the Greek Cypriot Administration in the Mediterranean Basin in 2011 (Gürel et al., 2014). Hence, following this statement, the government continued to award licenses and authorise companies to start drilling. The Greek Cypriot administration saw itself as the only sovereign under this status quo, due to its international recognition. Therefore, the Turkish Cypriots’ rights were postponed.

Nicos Anastasiadis replaced Christofias in 2013, and he also voted ‘’Yes’’ for the Annan Plan. However, he did not consider the Turkish Cypriots in the licensing and drilling process, and also underlined that energy is also an issue that concerns the EU and stated that the Eastern Mediterranean can become a reliable energy supplier (South EU Summit, 2019). Anastasiades has always underlined the necessity of a comprehensive solution in Cyprus and has used accusatory discourse regarding the presence of Turkey (South EU Summit, 2019).

Anastasiadis’ discourses are not different to previous leaders of the Greek Cypriot Community, who have consistently proclaimed the existence of one state in Cyprus and referred to the international law and UN Security Council Resolutions. Therefore, he has always believed that sovereignty applies purely to his government and also indicated that Turkish troops and ships conducting seismic surveys and drilling violate international law and the sovereignty of Cyprus. For instance, Kornilios Korniliou, permanent UN representative of the Greek Cypriot Administration, wrote a letter to UN Secretary General Guterres in March 2019 in which he protested Turkey’s seismic surveys in Blocks 1, 8, 9, 12 and reminded him that the government had already licensed blocks 8-9 for Eni and Total companies (Kathimerini Newspaper, March 6, 2019). Korniliou also said that Turkey’s presence in the related blocks violates the sovereign rights of Cyprus, which are stipulated by international law and he referred to the UNCLOS (Kathimerini Newspaper, March 6, 2019).

Mehmet Ali Talat also argued that East-Med project is not feasible economically, however Anastasiadis try to exclude Turkey from the projects by adding the major powers to process, which makes the problem more complicate (Interview with Mehmet Ali Talat, March, 2021).

The newly elected Prime Minister of Greece, Kyriakos Mitsokatis, made his first visit to the southern part of Cyprus and he focused on the Cyprus problem and the energy issue in his meeting with Anastasiadis. Mitsotakis also indicated that Turkey was the source of tension in the Eastern Mediterranean on the energy issue (Kathimerini Newspaper, 2019, July 29). Recently, Georgios Lakkotrypis, Minister of Energy for the GCA has repeated in an interview that Turkey’s allegations are not compliant with international law and underlined that the hydrocarbon issue has never been linked with a settlement of the Cyprus problem and emphasised that Cyprus designs its energy policy according to international law and UNCLOS (Cyprus News Agency, 2019).

Perspectives of Turkey and TRNC

Under normal conditions, the states involved in delimitation disputes are required to base their arguments on the law of the sea. In the Mediterranean case, however, the Cyprus problem itself also provides the basis for the legal arguments of all related parties besides the principles of the law of the sea (Başeren, 2013). Thus, the arguments of Turkey and the TRNC for a possible solution of delimitation of the maritime areas and hydrocarbon discoveries also reflects their positions in terms of the sovereignty debate in Cyprus.

As mentioned in previous sections, since Turkey is not party to the UNCLOS, delimitation in the region should be arranged on the basis of customary international law (Başeren, 2013). Accordingly, in delimiting maritime areas, Turkey and the TRNC base their legal positions on the principle of “equity”, which calls for consideration of all relevant circumstances and places emphasis the principles of proportionality of the length of adjacent/opposite coastlines and non-encroachment (Balık, 2018; İnan & Gözen, 2009). Moreover, referring to the semi-closed sea status of the Mediterranean, Turkey and TRNC hold their position in the spirit of international law of the sea, which says that the “states bordering an enclosed/semi-enclosed sea should cooperate with each other in the exercise of their rights and in the performance of their duties under this Convention” (UNCLOS, Article 123). Accordingly, delimitation of the continental shelf and EEZ in the Mediterranean, which is a semi-enclosed sea, should be arranged jointly “by agreement of all the related parties on the basis of principle of equity so as not to prejudice the sovereign rights and jurisdiction of other interested states/entities” (U.N. Doc. A/70/945-S/2016/541). Accordingly, Turkey, as a coastal state and concerned party, has the right to raise its objections in the context of the EEZ delimitation agreements that the GCA has signed unilaterally with Egypt, Israel and Lebanon.

All sources of the law of the sea (i.e., conventions/treaties, customary international law and decisions of international courts adopting delimitation on equity principle) support the arguments of Turkey and the TRNC (Başeren, 2013). The 1958 Convention on the Continental Shelf, 1982 UNCLOS and customary international law are of the same opinion that delimitation should be agreed among all actors by taking all relevant factors into consideration in line with the principle of equity and to reach to a just solution for all related parties. In addition, the ICJ also principally accepts that delimitation of sea areas in the disputed cases should be arranged “on the basis of the principle of equity” (Taşdemir, 2012). There are ample examples in international jurisprudence and state practices proving this principle. The most well-known ones include the 1969 North Sea Continental Shelf Case, 1977 England-France Continental Shelf Case and 1985 Libya-Malta Continental Shelf Case.

The insistence of Turkey and the TRNC on the delimitation through an agreement and negotiations by the participation of all relevant actors is compatible with their arguments on the sovereignty debate between the Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots. Referring to the fact that “sovereignty in Cyprus is emerging equally from the Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots” (U.N. Doc. 2019/2979), both Turkey and TRNC always insist that the sovereign rights of Turkish Cypriots are equal to those of Greek Cypriots over all resources in the land and sea areas of Cyprus. According to their position, delimitation as an issue is one of the dimensions of the comprehensive settlement of the Cyprus problem itself (U.N. Doc. A/63/828-S/2009/216). Without a settlement, the unacceptable and provocative steps of the Greek Cypriots disregard the legitimate and legal rights and interests of Turkey and the TRNC and introduce new conflicts to those that already exist among the relevant parties. To reverse such a scenario, Turkish Cypriots have always expressed their willingness to cooperate with the Greek Cypriots on the exploration and exploitation of the hydrocarbon resources of the island and have presented concrete proposals in the past. The latest proposal was presented by Mustafa Akıncı through the UN in early July 2019 with the objective of “turning the hydrocarbons issue into an area of efficient cooperation from an area of tension and conflict” (Presidency of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, 2019). This cooperative initiative envisages the establishment of a joint committee (with the purpose of exploring and exploiting oil and gas resources around Cyprus) with an equal number of representatives from both sides and would operate under the supervision of the UN with the EU taking part as an observer. Turkey fully backed the proposal considering that if it was accepted, it would “create a new cooperation era between the two sides, strengthen the regional peace, stability and cooperation and also create a conducive atmosphere for the settlement of the Cyprus question” (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2019). However, similar to the previous experiences on 24 September 2011 and 29 September 2012, the GCA turned down this renewed proposal and declined to discuss this issue with their interlocutors in the TRNC.

Caspian Sea delimitation model as a base for Eastern Mediterranean

Continental Shelf, EEZ and issues of NAVTEX have recently become reasons of the conflicts among littoral states in the Eastern Mediterranean. The parties try to maximise their own national interests in the region by signing bilateral treaties-agreements. However, such treaties don’t make contribution for solution of the problems in Eastern Mediterranean Basin. Even, such treaties make the problem more complicate. Therefore, Caspian Sea can be chosen as a functioning regime model and base for delimitation in the Eastern Mediterranean in where all littoral states (Russia, Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan) solved the problem by joining to the multilateral diplomatic conference in 2018.The littoral states had to solve the problem by negotiation for delimitation in Caspian Sea. Because the distances are less than 400 miles among the littoral states. Eventually, the littoral states in Caspian Sea had signed sui generis treaty which they accepted territorial sea for each state as 15 miles and can add 10 miles more and can reach to 25 miles too (Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea, 2018: Article 7). Additional to this, this convention suggests to the littoral states which they are with opposite coasts (Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea, 2018: Article 8).

The littoral states in the Eastern Mediterranean have similar ‘’geographic positions-conditions’’ with their neighbours as in Caspian Sea regarding the distances among themselves. These states; Egypt, Lebanon, Greece, Libya, Syria, Turkey, RoC (Greek Cypriots) and TRNC (De facto state-Turkish Cypriots) should solve the problem by diplomatic means at a multilateral diplomatic conference and then they may have agreement on the basis of sui generis conditions of the Eastern Mediterranean as the parties reached a convention in Caspian Sea. However, first of all, Cyprus problem should be solved comprehensively, or Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot leaderships should form a joint committee to participate a multilateral conference to solve the problem of EEZ and may be a kind of confidence building measure for the solution of Cyprus problem too.

Conclusion

Discoveries of natural gas in the Mediterranean are likely to reduce energy dependency of the littoral states and develop cooperative initiative on the regional basis. However, under the current conditions, the reality is far from this expectation due to the power asymmetry, diplomatic isolation and unstable relations among the regional countries that obstruct any attempt for reconciliation, effective consultation, and regional cooperation. Since the hydrocarbon issue is directly related to the sovereignty dimension of the Cyprus problem, any development in relation to the hydrocarbon discoveries in the contested waters around Cyprus has been amplifying the different positions of the parties on the maritime borders and sovereignty issues which eventually escalated the already existing tension. Turkish and Greek Cypriots have opposing claims and arguments in terms of the discoveries and use of hydrocarbon resources around Cyprus and the share of their revenues. The disagreements between them mainly emerge from the dispute over their sovereignty rights in the Mediterranean. This has in turn emphasised the most crucial question of sovereignty from a much more general framework. While the GCA argues that as the internationally recognised side of the island, they can conclude maritime border agreements with the third states and use its sovereignty-based rights to explore and exploit the existing resources in its own maritime jurisdiction areas even in the lack of a political settlement, the Turkish Cypriot leadership opposes the actions of GCA regarding the delimitation of maritime borders and discovery of the hydrocarbon resources around Cyprus. The latter argues that all Greek Cypriot actions in the region involve the “unilateral use of sovereign rights” on the international basis excluding the rights of Turkish Cypriots. Since the Turkish Cypriots are co-owners of this sovereignty by virtue of their equal status of being “one of the equal constituent communities” of the 1960 RoC, any unilateral action by the GCA is recognised a breach of the legitimate and legal rights of the former as well as their national interests.

Although regional challenges in the Eastern Mediterranean and national realities in the individual regional countries emphasise the need for cooperation, thus far, the discovery of energy resources in the Eastern Mediterranean has exacerbated the long-standing disagreements and deepened the existing stalemate between Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots. Since the Cyprus hydrocarbons issue extends beyond its economic, strategic, and energy-related matters, it has emerged as a fault line that is sustaining the sovereignty rhetoric of both parties. As a way of re-asserting the parties’ sovereign rights, the issue of natural resources around Cyprus reflects the long-established sovereignty conflict between Turkish and Greek Cypriots and has a clear impact on their claims in terms of their rights over the island’s resources. Thus, discoveries and explorations of those resources have revived the sovereignty conflict that has existed for many years. More importantly, sovereignty disputes are likely to continue in the lack of a peaceful comprehensive settlement of the long-lasting Cyprus problem that would meet the demands of both sides.

References

Agreement Between the government of the State of Israel and the Republic of Cyprus, on Delimitation of the Exclusive Economic Zone, December 17, 2010, Article 1, retrieved from https://www.un.org/depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/ PDFFILES/TREATIES/cyp_isr_eez_2010.pdf

Agreement between the Republic of Cyprus and the Arab Republic of Egypt on theDelimitation of the Exclusive Economic Zone, February 17, 2003, Article 1,https://www.un.org/depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/TREATIES/EGY-CYP2003EZ.pdf

Alah, K., & Nezhad, D. (2017). States Ownership and Sovereignty over Marine Resources. International Journal of Scientific Study, 5(4), 1040-1047.

Balık, İ. (2018). Türkiye’nin Deniz Yetki Alanları ve Kıyıdaş Ülkelerle Yetki Alanı Anlaşmazlıkları [Maritime Jurisdiction Areas of Turkey and Conflicts Related to Jurisdiction Area with Riparian Countries]. Kent Akademisi, 11(1), 95.

Başeren, S. H. (2010). Dispute over Eastern Mediterranean Maritime Jurisdiction Areas. Türk Deniz Araştırmaları Vakfı Yayınları.

Başeren, S. H. (2013). Doğu Akdeniz’de Yetki Alanları Sınırlandırması Sorunu: Tarafların Görüşleri, Uluslararası Hukuk Kurallarına Göre Çözüm ve Sondaj Krizi [The Problem of Limitation of Jurisdiction in the Eastern Mediterranean: Views of the Parties, Solution according to the Rules of International Law and the Drilling Crisis]. In S. H. Başeren (Ed.), Doğu Akdeniz’de Hukuk ve Siyaset (pp. 285-286). A. Ü. Siyasal Bilgiler Fakültesi Yayınları.

Caporaso, J. A. (2000). Changes in the Westphalian Order: Territory, Public Authority, and Sovereignty. International Studies Review, 2(2), 1-28.

Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea, August 12, 2018, http://en.kremlin.ru/supplement/5328

Çubukçuoğlu, S. S. (2014). Turkey’s Exclusive Economic Zone in the Mediterranean Sea: The Case of Kastellorizo [Unpublished master’s thesis]. The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. Retrieved on July 06, 2019, from https://www.academia.edu/9532225/Turkeys_EEZ_in_the_Mediterranean_Sea_ The_Case_of_Kastellorizo

Cyprus Hydrocarbons Company. (2019a). Legal Status. https://chc.com.cy/about-us/legal-status/

Cyprus Hydrocarbons Company. (2019b). https://chc.com.cy/activities/brief-outline/

Cyprus Hydrocarbons Company. (2019c). https://chc.com.cy/activities/#activities-in-cypriot-eez

Cyprus News Agency. (2019, August 11). No link between hydrocarbon activities and settlement talks in

Cyprus, Energy Minister says. Retrieved on August 12, 2019, from http://www.cna.org.cy/WebNews-en.aspx?a=ea2c755ad29846abab08f86 5514f6f7f

Ece, N. J. (2017). Doğu Akdeniz’de Münhasır Ekonomik Bölge: Sınırlandırma Anlaşmaları, Paydaşlar ve Stratejiler [Exclusive Economic Zone: Delimitation Agreements, Stakeholders (Parties) and Strategies Translation in brackets]. Journal of ETA Maritime Science, 5(1), 81-94.

South EU Summit (2019, January 29). ‘2019 Should Be the Year of Change – and A Change We Deliver’: An Interview with Cypriot President Nicos Anastasiades. Retrieved on August 2, 2019, from https://www.southeusummit.com/europe/ cyprus/2019-should-be-the-year-of-change-and-one-we-deliver-an-interview-with-cypriot-president-nicos-anastasiades/

Ellinas, C. (2018, December 2). EastMed gas pipeline increasingly doubtful. The Cyprus Mail. https://cyprus-mail.com/2018/12/02/eastmed-gas-pipeline-increasingly-doubtful/

Energy World Digital. (2019). Leaders of Cyprus, Greece and Israel signed on EastMed pipeline. Retrieved on March 22, 2019, from https://www.energyworldmag.com/ leaders-of-cyprus-greece-and-israel-signed-agreement-on-eastmed-pipeline/

Euractiv. (2022, April 8). Washington kills EastMed pipeline project for good. https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/short_news/washington-kills-eastmed-pipeline-project-for-good/

Filis, A., & Arcas, R. (2013). Legal Aspects of Inter-State Maritime Delimitation in the Eastern Mediterranean Basin. Oil, Gas & Energy Law Intelligence Special Issue, 11(3). from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256061151_Legal_Aspects_of_Inter-State_Maritime_Delimitation_in_the_Eastern_Mediterranean_Basin.

Geropoulos, K. (2017, December 5). Greece, Cyprus, Italy, Israel sign MoU for East Med gas pipeline. New Europe. https://www.neweurope.eu/article/greece-cyprus-italy-israel-sign-mou-east-med-gas-pipeline/

Gürel, A., & Le Cornu, L. (2013). Turkey and Eastern Mediterranean Hydrocarbons. Global Political Trends Center Publications. Retrieved on December 12, 2019, from http://www.gpotcenter.org/dosyalar/TRhydrocarbons_Gurel_Lecornu_2013.pdf

Gürel, A., Fiona, M., & Tzimitras, H. (2013). The Cyprus Hydrocarbons Issue: Context, Positions and Future Scenarios. PRIO Report, (1/2013), Retrieved on July 10, 2019, from https://cyprus.prio.org/Publications/Publication/?x=1172

Gürel, A., Tzimitras, H., & Faustmann H. (2014). East Mediterranean Hydrocarbons: Geopolitical Perspectives, Markets, and Regional Cooperation. Peace Research Insitute Oslo Cyprus Center (PRIO), Report: 3.

IGI Poseidon. http://www.igi-poseidon.com/en/eastmed

İnan, Y., & Gözen, M. P. (2009). Turkey’s Maritime Boundary Relations. In M. Kibaroğlu (Ed.), Eastern Mediterranean Countries and Issues (pp. 153-211). Foreign Policy Institute.

Talat, M. A. (2021. March 15th). Personal Communication [Personal Interview)

Iperkiyou Ekseterikon Kypros. (2019). Diefneks Nomiko Plasio. http://www.mfa.gov.cy/mfa/mfa2016.nsf/mfa83_gr/mfa83_gr?OpenDocument

Kathimerini Newspaper. (2019, July 29). End of Turkish occupation of Cyprus is 'top priority,' Greek PM says on Nicosia visit”. Retrieved on August 6, 2019, from http://www.ekathimerini.com/243074/article/ekathimerini/news/end-of-turkish-occupation-of-cyprus-is-top-priority-greek-pm-says-on-nicosia-visit

Kathimerini Newspaper. (2019, March 6). Cyprus protests Turkish activity in its EEZ. Retrieved on 2019, August 6, from http://www.ekathimerini.com/2383 50/article/ekathimerini/news/cyprus-protests-turkish-activity-in-its-eez

Kaya, İ. S. (2019, May 19). Turkey’s Legal Position in the Mediterranean. The New Turkey. Retrieved on July 18, 2019, from https://thenewturkey.org/turkeys-legal-position-in-the-eastern-mediterranean

Krasner, S. D. (1988). Sovereignty: An Institutional Perspective. Comparative Political Studies, 21(1), 66-94.

Nevers, R. (2015). Sovereignty at Sea: States and Security in the Maritime Domain. Security Studies, 24(4), 597-630.

Note No. 2004/Turkuno DT/4739 dated 2 March 2004 from the Permanent Mission of Turkey to the United Nations.

Özgür, H. K. (2017). Eastern Mediterranean Hydrocarbons: Regional Potential, Challenges Ahead, and the Hydrocarbon-ization’ of the Cyprus Problem. Perceptions: Journal of International Affairs, 22(2-3), 31-56.

Presidency of the Republic of Turkey. (2020). Strategic Step the Eastern Mediterranean Equation: Memorandum of Understanding Between Turkey and Libya, Directorate of Communications.

Presidency of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. (July 13, 2019). President Akıncı Made a New Proposal on the Hydrocarbons Issue to the Greek Cypriot Leader. Retrieved on August 02, 2019 from https://kktcb.org/en/president-akinci-made-a-new-proposal-on-the-hydrocarbons-issue-7073

Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2011, September 21). Press Statement on the Continental Shelf Delimitation Agreement Signed Between Turkey and the TRNC. Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved on July 26, 2019, from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/no_-216_-21-september-2011_-press-statement-on-the-continental-shelf-delimitation-agreement-signed-between-turkey-and-the-trnc.en.mfa)

Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2019, July 13). Press Release Regarding the New Cooperation Proposal of TRNC on Hydrocarbon Resources. Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved on August 02, 2019 from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/no_203_-kktc-nin-hidrokarbon-kaynaklarina-iliskin-yeni-isbirligi-onerisi-hk.en.mfa

Statement of Demetris Christofias. (2011). President of the Republic of Cyprus, At the 66th Session of the United Nations General Assembly”, New York, September 22, 2011, https://gadebate.un.org/sites/default/files/gastatements/66/CY_en.pdf

Taşdemir, F. (2012). Kıbrıs Adası Açıklarında Petrol ve Doğalgaz Arama Faaliyetleri Kapsamında Ortaya Çıkan Krizin Hukuki, Ekonomik ve Siyasi Boyutları [Legal, Economic and Political Aspects of the Crisis within the Scope of Oil and Natural Gas Exploration Activities off the Cyprus Island]. Ankara Strateji Enstitüsü.

Tzanetakou, N. (2019). East Med funding secured? Independent. Balkan News Agency. Retrieved on January 21, 2019, from https://balkaneu.com/east-med-funding-secured-2/

U.N. Doc. A/61/1011-S/2007/456; U.N. Doc. A/70/945-S/2016/541.

U.N. Doc. A/61/1027-S2007/487.

U.N. Doc. A/61/727-S2007/54; U.N. Doc. A/68/902.

U.N. Doc. A/61/727-S2007/54.

U.N. Doc. A/63/828-S/2009/216.

U.N. Doc. A/71/875-S/2017/321.

U.N. Doc. A/73/827-S/2019/297.

UNCLOS, Article 123.

UNCLOS, Article 56,

UNCLOS, Article 76/1.

UNCLOS, Article 77.

UNCLOS, Articles between 279-299.

United Nations Security Council Resolution 186, 4 March 1964.

United Nations Security Council Resolution 541, 18 November 1983.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 November 2022

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-998-6

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

-

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-156

Subjects

Eastern Mediterranean, economy, politics, energy, geopolitics, security, refugee crisis, nationalism, populism, democratization

Cite this article as:

Oğurlu, E., & Özsağlam, M. T. (2022). Reflections on the Sovereignty Dispute for Hydrocarbon Resources in the Eastern Mediterranean. In M. T. Özsağlam (Ed.), Politics, Economy, Security Issues Hidden Under the Carpet of Mediterranean, vol -. (pp. 1-29). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/BI.20221101.1