Abstract

During the COVID-19 crisis, several measures were implemented to limit the transmission of the virus including border control and movement restrictions. These measures have had a significant impact on the tourism industry and tourists’ behaviour globally. This paper aims to explore the impact of COVID-19 on the travel decisions of Malaysian millennials, as the key contributor to the tourism industry. A qualitative research method was employed with semi-structured interviews were carried out on the selected millennials for the data collection process. From the transcribed data, themes were developed using the constant comparative method of analysis. The findings highlighted a significant change in travel behaviour whereby, Malaysian millennials prefer to travel to local low-density destinations as opposed to overseas in the advent of the pandemic. The study also established a conceptual framework explaining the changes in the travel decisions of millennials. The two key factors driving the changes are perceived travel risk and travel constraints.

Keywords: Covid-19, Malaysia, millennials, travel constraint, travel decision

Introduction

The Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has affected almost all countries, with more than 56 million infected and 6 million fatalities globally (World Health Organization, 2022). The unprecedented scale of the impact was primarily attributed to inter-country travel, with the virus spreading from its epicentre in Wuhan, China, into a global pandemic (Teeroovengadum et al., 2021). In response to the pandemic, many governments have enacted territorial approaches via lockdown and travel restrictions to curb the spread of the virus (OECD, 2020; Tang, 2022). Notably, the restrictions affected global economies, particularly in the tourism industry. The COVID-19 pandemic is shaping up to be the biggest challenge for the tourism industry as the spread of the virus is invariably linked to travel (Joppe, 2020).

The Malaysian government implemented strict border control and several movement control restrictions from March 2020 to March 2022, limiting both incoming tourists and domestic tourism (Hanafiah et al., 2021; Hashim et al., 2021). The pandemic caused a 96.9% drop in incoming tourists in 2021 against pre-pandemic years (Tourism Malaysia, 2022) and nearly RM130 billion less in internal tourism consumption compared to 2019 (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2021). As the country was preparing to enter the endemic stage, leisure travel was encouraged, border control was lifted, and the tourism industry was allowed to operate with strict operating procedures (Hanafiah et al., 2021). Globally, millennials have been recognised as a crucial player in the tourism industry (Azazi & Shaed, 2020; Gengeswari et al., 2021). In Malaysia, 40% of the tourists are millennials (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2021), thus highlighting the segment’s importance. A critical question in catalysing the recovery of the Malaysian tourism industry is how the pandemic has affected travel decisions among millennials.

This study aims to explore the impact of COVID-19 on the travel decisions of Malaysian millennials via a qualitative approach. By presenting the perspectives of Malaysian millennials, this study will add to the body of knowledge and assist policymakers and industry players in attracting more millennial travellers post-pandemic.

Literature Review

The unprecedented pandemic outbreak has caught the interest of researchers from all disciplines, especially in tourism and hospitality studies (Ahmad et al., 2022; Gupta et al., 2023; Li et al., 2022; Mirzaei et al., 2023; Tergu et al., 2022). Mirzaei et al. (2023) investigated the changes in Iranian tourist behaviour post-pandemic and found that destination hygiene has become a motivating factor. Similarly, Shin et al. (2022) developed a framework explaining travel decisions. Nguyen et al. (2021) focused their study on the Vietnamese travel intention and concluded that the intention is influenced by perceived risk, perceived behavioural control, self-efficacy and subjective well-being. Among the most cited determinants of travel decisions are perceived risk (Bhatta et al., 2022; Fan et al., 2023; Tergu et al., 2022), perceived safety (Aebli et al., 2022; Md. Aris et al., 2021; Teeroovengadum et al., 2021) and structural constraint (Humagain & Singleton, 2021; Karl et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022).

Against the backdrop of the Malaysian context, limited studies were dedicated to understanding the changes in travel behaviour with the advent of COVID-19. Aziz and Long (2022) discussed the interplay between travel constraints, perceived travel risk and travel intention among Malaysians after the global health crisis. A similar study by Hanafiah et al. (2021) concluded that perceived health risks negatively impacted travel attitude and future travel intention. Interestingly, Dias et al. (2021) found that married respondents prioritised travel factors differently from single respondents. Malaysian married couples consider cleanliness, social distancing and mask wearing mandate as essential factors in travel decision-making. Following the limited understanding of the mechanism of Malaysian millennials' travel behaviour change, this study aims to fill the gap with this exploratory research.

Research Methods

This study aims to better understand millennials’ travel decisions by using an interpretivism paradigm, which focuses on studying “how individuals see, comprehend, and interpret the world” (Patton, 2002). This study employs the qualitative research approach that allows the researcher to understand the impact of the unprecedented pandemic on travel decisions. The nature of the study, which focuses on the changes in human behaviour, also suggests that an exploratory methodology is the most appropriate approach (Schreier, 2012).

In this study, six semi-structured interviews were conducted between May and June 2022 via Zoom and Google Meet platforms, allowing researchers to gather information from participants by posing relevant questions. The virtual interview is the preferred data collection approach in the post- pandemic era because it helps to minimise face-to-face interaction and limit the transmission of the virus (Sutherland et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2021). Secondly, this approach saves time and costs (Deakin & Wakefield, 2014; Saarijärvi & Bratt, 2021). However, the use of a virtual interview is not without its limitations. The interviewer will only be able to observe the interviewee and interpret the non-verbal cues to the extent to which the camera is positioned. Both parties must also have a stable internet connection with good quality microphone and camera (Saarijärvi & Bratt, 2021). In this study, the participants have been informed of the technological requirements ahead of the scheduled interview.

The six participants for the study were chosen via a combination of purposive and convenience sampling methods. Purposive sampling is predominant in qualitative studies because it zooms into the parties involved with the phenomenon of interest (Tie et al., 2019). The inclusion criteria for the study were: millennials born between 1981 and 1996 (Lindner, 2017; Siddharthan, 2014) and have travelled before the onset of the pandemic. Due to resource constraints, millennials amongst the researchers’ family and friends were identified to participate in the research which explained the use of a convenience sampling technique. Table 1 gives an overview of the participants’ profiles.

The sessions were guided by open-ended interview questions, which helped to ascertain if there were any changes to the post-pandemic travelling pattern and its underlying reasons. The questions consisted of travel preferences and experiences both before and after the pandemic. Probing questions were also asked when the initial response to the question was insufficient. For documentation purposes, the study relied heavily on several online software, Scre.Io for audio-visual recording and Rev AI and Amberscript for verbatim transcription. The transcripts were later manually checked and amended where necessary to ensure the accuracy of information.

Data Analysis

This study follows the grounded theory approach by adopting the constant comparative method in analysing the data (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Following the constant comparative method, data is dissected into smaller pieces in which they are continually evaluated for similarities and differences. Similar data are then grouped under the same conceptual category, and each category is further refined and finally consolidated around a core category. Corbin and Strauss (2015) posited that the core categories should be able to summarise the overall theme of the study. Data analysis was carried out through three constant comparative coding phases: open, axial, and selective.

In the first coding phase, each researcher studied the interview transcripts independently and assigned the open codes by scrutinising the transcripts line by line (Strauss, 1987). A comparison of the output revealed an extensive list of codes with huge discrepancies. Hence, the codes were revised through several discussions until consensus was obtained and the open codes were finalised. The procedure yielded a total of 40 open codes. O'Connor and Joffe (2020) highlighted that the number of codes identified must be controlled and should be aligned with the research questions. Extremely complex coding frames frequently include codes with a low frequency of occurrence, making it difficult for coders to become accustomed to the codes in assessing the data (Hruschka et al., 2004). MacQueen et al. (1998) suggested an upper limit of 30 codes, while Hruschka et al. (2004) suggested 20 codes. Following the recommendation, the open coding process was repeated to reduce the codes to 23.

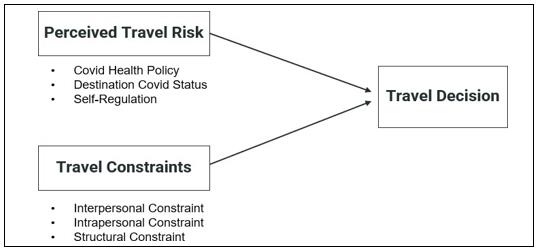

Next, the open codes were re-examined to identify potential relationships and similarities. The open codes with similar concepts were grouped in axial categories, which resulted in six axial categories. Codes lacking explanatory value or similar meaning were eliminated (Corbin & Strauss, 1990). The six axial categories are COVID-19 health policy, COVID-19 destination status, self-regulation, structural constraint, interpersonal constraint and intrapersonal constraint. Based on the constant comparative method, reiterative refinement was carried out continuously throughout the data analysis process. The final phase of coding was selective coding. This step was centred on linking the axial codes and identifying the core categories. As a result, the two most essential criteria for understanding the travel decision post-pandemic among Malaysian millennials were established.

Results and Findings

The data analysis process was driven by the quest to answer how Covid-19 has impacted the travel decision of Malaysian millennials. An in-depth data analysis highlighted two ways the travel decision has changed. First, the millennials are more inclined to travel within Malaysia. Below are the extracts of verbatim conversations with the participants.

“Before the pandemic, my travel history is a combination of domestic and international travel. Now, my travel pattern has changed where I only look into domestic destinations.” [Participant 1]

“Typically, I travelled both locally and internationally. But for the time being, I prefer travelling domestically.” [Participant 3]

“Before the pandemic, I travelled domestically six times and internationally once a year. Now, my travel decision has not changed and remained the same.” [Participant 5]

“With COVID-19, I travelled more domestically because I trust the SOP in Malaysia.” [Participant 6]

A survey by Tourism Malaysia (2020) also found that 71.3% of Malaysians favour domestic travel over international travel with the advent of COVID-19. Similar studies from various countries have come to the same conclusion, evidence that the finding is not limited to the Malaysian context. For example, Machová et al. (2021) found that the Slovaks predominantly prefer to travel domestically in the future as in the case of the Dutch (Isaac & Keijzer, 2021), Nepalese (Bhatta et al., 2022) and Korean (Lee & Han, 2023). Among the factors contributing to the change in travel preference are cost consideration and lower perceived risk (Machová et al., 2021; Yusof, 2021).

The second noticeable trend in the travelling behaviour of Malaysian millennials is the inclination to select destinations with a lower tourist density that are nature related. As highlighted by Participant 6, “I notice after COVID-19, I tend to go to places that I’ve never been before since the famous places like Penang and Malacca are very crowded, so I went to nature destinations”. Participant 5 also agrees, “Instead of going to the city centre, I will choose a nature destination with fewer people that are less crowded”. The preference for less crowded places has also been highlighted by several other post- pandemic tourism studies (Aydin et al., 2021; Bhatta et al., 2022). The data analysis shed light on the factors contributing to the changes in travel decisions, namely perceived travel risk and travel constraints. The selective codes and their subcategories are discussed further in the following section. All figures and tables should be referred to in the text and numbered in the order in which they are mentioned.

Selective Code 1 – Perceived Travel Risk

The first selective code identified following the data analysis is perceived travel risk. It is the tourist’s perception of uncertainty and potential adverse outcomes at a travel destination (Gupta & Sajnani, 2019; Gupta et al., 2023; Matiza, 2022). Three axial codes were grouped from the coding process to form ‘perceived travel risk’. The better the extent of COVID-19 health policy, COVID-19 status at destination and self-regulation, the lower the perceived travel risk is.

COVID-19 Health Policy

The most important consideration for the interviewed millennials was the national COVID-19 health policy, which reflects the extent to which the government enforces policies to limit the transmission of COVID-19. Should the government manage the pandemic well, the perceived travel risk will become lower, and tourists will be more inclined to visit the destination. One participant stated that the local government's stand would be considered when planning to travel overseas. Participant 6 travelled more domestically becauseAnother aspect often mentioned is the public vaccination mandate and mask- wearing policy.

COVID-19 Destination Status

An extension of the previous sub-category, COVID-19 destination status refers to the perceived protection at the potential travel destination facility. One indication is the number of active COVID-19 cases in the locality. Several participants mentioned that they would only consider travelling to destinations with low COVID-19 cases. Participant 1 highlighted that the option to travel internationally would only be contemplated ifAs part of COVID-19 destination status, Participant 6 mentioned the importance of vaccinating staff members to help tourists feel safer. In certain countries where COVID-19 vaccination is not mandated, tourism market players often have the entire fleet of staff vaccinated as a promotion to attract more tourists (Shah Alam et al., 2023). The final aspect of this sub-category is the enforcement of COVID-19 standard operating procedures (SOP) at the destination, as stated by Participant 6, “. Destinations that adopt COVID-19 SOP are preferable for Malaysian millennials.

Self-Regulation

Self-regulation is the affinity of an individual to voluntarily comply with COVID-19 measures such as wearing a face mask, though the government has lifted the requirement. Due to the increased awareness, several participants said they voluntarily wear the face mask and will continue to do so. Other examples of self-regulation include doing a periodic COVID-19 self-test and using a hand sanitiser. Below are the extracts of verbatim conversations with the participants.

“I do travel locally but with a lot of considerations. We have our PPE, our face mask is always on and the hand sanitiser is always with us”. [Participant 1]

“For me, I will still wear a mask since I strongly agree that a face mask is important in minimising the risk for COVID-19.” [Participant 4]

“For precautionary purposes, I will always do RTK. I will also ask my husband to do RTK as well.” Participant 6]

Selective Code 2 - Travel Constraints

The second factor influencing the travel decisions of Malaysian millennials is travel constraints. It is the factors that inhibit individuals from choosing a destination, spending more time at the destination, or reaching the desired level of satisfaction (Humagain & Singleton, 2021; Mei & Lantai, 2018; Shin et al., 2022). Based on the interview, three sub-categories of travel constraints were identified: intrapersonal, interpersonal, and structural. The findings are aligned with the Leisure Constraints Theory by Crawford and Godbey (1987), in which the factors impeding participation in leisure activities were explained.

Intrapersonal Constraint

The first sub-category of travel constraints is an intrapersonal constraint which refers to an individual’s psychological state that manifests in behaviour or the physical state that may influence travel decisions (Karl et al., 2021). The first aspect of intrapersonal constraint is travel risk perception. The risk perception was manifested in many ways by the participants, including;

“I do have a one-year-old daughter which I consider falls into the high-risk group. That is part of the consideration when travelling.” [Participant 1]

“I have three kids and two of them are below two years old and do not have vaccines. I will be more cautious whenever travelling because of my kids.” [Participant 3]

“If I go somewhere for vacation, my family and I will wear face masks, but what about others? I am not sure if other people are having illness or COVID-19.” [Participant 4]

Another aspect of intrapersonal constraint is attitude and preference. The advent of COVID-19 has made the general public more aware of hygiene. Many participants expressed their preference for destinations with good hygiene practices;

“I prefer destinations with good hygiene and cleanliness. Before this I didn't really mind about hygiene and everything but now I need to be more careful, hygiene is my priority now; hygiene and cleanliness.” [Participant 3]

“COVID-19 has made me take more precautions, taking hygiene more seriously.” [Participant 6]

Interpersonal Constraint

An interpersonal constraint is formed by social interactions and relationships with other individuals such as friends, families and colleagues that influence the preference for leisure activities. Specifically, the interpersonal constraint is the peer pressure that drives the travel decision. Participant 6 mentioned that peers influence the decision to travel, “As more and more peers travel, one will be inclined to travel, too.” As shown by Xie and Ritchie (2018), the extent of the interpersonal constraint depends on many factors, including age. The findings show that millennials are influenced by peer pressure in making travel decisions.

Structural Constraint

The content analysis of the participants’ transcripts also highlighted structural constraints or the intervening physical factors that inhibit actual travelling after the destination preference has been formed (Shin et al., 2022). First, all participants attested that social distancing practice is a critical consideration when choosing a destination and prefer to travel to a less crowded one. The importance of crowd density was highlighted by all participants “I will choose the location which is less crowded”, “Now we even go to staycation nearby our house but still we look for places that are less crowded”, “For domestic travel, I will go to places that are less crowded” and “I notice after COVID-19, I tend to go to places that I’ve never been before since the famous places like Penang and Malacca are very crowded”. The change in travel decisions is understandable since social distancing practice will be able to minimize the crowd and lower the risk of COVID-19 transmission (World Health Organization, 2022).

Another structural constraint quoted by the participants is service availability. In the face of the pandemic, many businesses succumbed to the pressure and closed their businesses. On the other spectrum, the business is still operating with limited services. Participant 6 pointed out, "I have a few favourite restaurants that I like to eat at when I go to Kuantan, but now they are closed”. Similarly, Participant 1 mentioned that not all facilities are available for use. The third sub-category is financial constraint. During the pandemic, many services charged higher to recoup revenue losses. The entry procedures for some destinations include quarantine and medical tests, which increase the overall cost. The excerpts below further stressed the point;

“Looking at the budget as well because, during this off-pandemic season, all prices hike up.” [Participant 2]

“I will choose a country with fewer COVID-19 procedures because for some countries you need to do a PCR test and I will avoid those countries because it is costly.” [Participant 5]

“If I want to go overseas, the flight tickets are very expensive nowadays.” [Participant 6]

Conclusion

This study explored the impact of COVID-19 on the travel decision of Malaysian millennials. The findings indicated that the tourism trends among Malaysian millennials has shifted towards new domestic attractions that are nature related with less crowd. This is in line with several other studies conducted outside of Malaysia (Lee, 2021; Spalding et al., 2021). More importantly, the study also established a conceptual framework for millennials' travel decisions. Factors influencing travel decisions have been identified, perceived travel risk and travel constraints. The framework is depicted in more detail in Figure 1.

These findings complemented the evidence-based research on the effects of COVID-19 on travel decisions. From a practical standpoint, it has highlighted the factors the millennials are considering regarding travelling. This enables the industry player to cater to the needs and preferences of the millennials and ultimately boost the tourism industry in Malaysia.

This study is subject to several limitations, all of which must be considered. First, the research is based on a qualitative design that incorporates responses from several Malaysian millennials and may not necessarily allow generalisation of the results. This study, however, offers a compelling argument by taking an exploratory posture to inspire more empirical research. In order to assess the pandemic’s effects on the tourism industry and the millennials’ response, robust empirical research is required. Future studies may operationalise the two core categories and their subcategories to enhance the literature further. Although some similar studies have focussed on the impact of health outbreaks on tourism behaviour, the magnitude of the present pandemic is almost unheard of in this century. Therefore, it is highly advised that measurement be developed to examine the effects of the outbreak and the corresponding changes in tourism behaviour.

The second limitation is the scope of the study, which was limited to Malaysian millennials. The findings may not be applicable in different contexts, and more factors may emerge that were not established in the current study. Future studies could fill this gap by expanding the target participant to cover the entire population or even based the study on a different geographical context. It is also crucial to keep in mind that the pandemic situation is continuously developing and that factors that are relevant now—such as the mandatory face mask policy or contact tracing mechanism, might not be as significant in the future. As a result, investigations that consider the temporal shift are more critical. More studies devoted to the COVID-19 pandemic would undoubtedly be needed in the future to ensure that literature accurately reflects its evolution and suggests strategies to lessen its effects.

References

Aebli, A., Volgger, M., & Taplin, R. (2022). A two-dimensional approach to travel motivation in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(1), 60-75. DOI:

Ahmad, N., Harun, A., Khizar, H. M. U., Khalid, J., & Khan, S. (2022). Drivers and barriers of travel behaviors during and post COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic literature review and future agenda. Journal of Tourism Futures. DOI: 10.1108/jtf-01-2022-0023

Aydin, B., Arica, R., & Arslanturk, Y. (2021). Yeni Koronavirüs'ün (COVID-19) Seyahat Risk Algısı Üzerindeki Etkisi [Impact of Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) on Travel Risk Perception]. Journal of Yaşar University, 16(61), 378-392. DOI:

Azazi, N. A. N., & Shaed, M. M. (2020). Social media and decision-making process among tourists: A systematic review. Jurnal Komunikasi: Malaysian Journal of Communication, 36(4), 395-409. DOI:

Aziz, N. A., & Long, F. (2022). To travel, or not to travel? The impacts of travel constraints and perceived travel risk on travel intention among Malaysian tourists amid the COVID-19. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 21(2), 352-362. DOI:

Bhatta, K., Gautam, P., & Tanaka, T. (2022). Travel Motivation during COVID-19: A Case from Nepal. Sustainability, 14(12), 7165. DOI: 10.3390/su14127165

Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3-21. DOI:

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research (4 Ed.). SAGE Publications.

Crawford, D. W., & Godbey, G. (1987). Reconceptualizing barriers to family leisure. Leisure Sciences, 9(2), 119-127. DOI:

Deakin, H., & Wakefield, K. (2014). Skype interviewing: reflections of two PhD researchers. Qualitative Research, 14(5), 603-616. DOI:

Department of Statistics Malaysia. (2021). Tourism satellite account 2020. https://v1.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/cthemeByCat&cat=111&bul_id=SXp2ZUF0TGx2OTU0YXo2YXZ1QUMydz09&menu_id=TE5CRUZCblh4ZTZMODZIbmk2aWRRQT09

Dias, C., Abd Rahman, N., Abdullah, M., & Sukor, N. S. A. (2021). Influence of COVID-19 Mobility-Restricting Policies on Individual Travel Behavior in Malaysia. Sustainability, 13(24), 13960. DOI:

Fan, X., Lu, J., Qiu, M., & Xiao, X. (2023). Changes in travel behaviors and intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic and recovery period: A case study of China. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 41, 100522. DOI:

Gengeswari, K., Zain, u.-A. J., Boh, M., Eng, L. S., Khaw, K. C., Loo, H. X., & Sia, P. C. (2021). Domestic travel intention post COVID-19 pandemic – what matters the most to millennials? Journal of Management Info, 8(2), 134-148.

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago Aldine.

Gupta, V., & Sajnani, M. (2019). Risk and benefit perceptions related to wine consumption and how it influences consumers’ attitude and behavioural intentions in India. British Food Journal, 122(8), 2569-2585. DOI: 10.1108/bfj- 06-2019-0464

Gupta, V., Cahyanto, I., Sajnani, M., & Shah, C. (2023). Changing dynamics and travel evading: a case of Indian tourists amidst the COVID 19 pandemic. Journal of Tourism Futures, 9(1), 84-100. DOI:

Hanafiah, M. H., Md Zain, N. A., Azinuddin, M., & Mior Shariffuddin, N. S. (2021). I'm afraid to travel! Investigating the effect of perceived health risk on Malaysian travellers' post-pandemic perception and future travel intention. Journal of Tourism Futures. DOI:

Hashim, J. H., Adman, M. A., Hashim, Z., Mohd Radi, M. F., & Kwan, S. C. (2021). COVID-19 Epidemic in Malaysia: Epidemic Progression, Challenges, and Response. Frontiers in Public Health, 9. DOI: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.560592

Hruschka, D. J., Schwartz, D., St.John, D. C., Picone-Decaro, E., Jenkins, R. A., & Carey, J. W. (2004). Reliability in Coding Open-Ended Data: Lessons Learned from HIV Behavioral Research. Field Methods, 16(3), 307-331. DOI:

Humagain, P., & Singleton, P. A. (2021). Exploring tourists' motivations, constraints, and negotiations regarding outdoor recreation trips during COVID-19 through a focus group study. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 36, 100447. DOI:

Isaac, R. K., & Keijzer, J. (2021). Leisure travel intention following a period of COVID-19 crisis: A case study of the Dutch market. DOI:

Joppe, M. (2020). Trapped tourists: how is the coronavirus affecting travel? https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/02/the- coronavirus-will-hit-the-tourism-and-travel-sector-hard/

Karl, M., Sie, L., & Ritchie, B. W. (2021). Expanding travel constraint negotiation theory: An exploration of cognitive and behavioral constraint negotiation relationships. Journal of Travel Research, 61(4), 762-785. DOI:

Lee, S. (2021). Analysis of positive feelings toward tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Civilization Special Issue of Covid-19, 63-67.

Lee, S., & Han, H. (2023). A new tourism paradigm and changes in domestic tourism for married Koreans in their 30s and 40s. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(8), 1341-1353. DOI:

Li, X., Liu, J., Su, X., Xiao, Y., & Xu, C. (2022). Exploration of Leisure Constraints Perception in the Context of a Pandemic: An Empirical Study of the Macau Light Festival. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. DOI:

Lindner, J. (2017). Hotel guest engagement: Retaining the millennial traveler. Florida State University.

Machová, R., Korcsmáros, E., Esseová, M., & Marča, R. (2021). Changing trends of shopping habits and tourism during the second wave of COVID-19 – International comparison. Journal of Tourism and Services, 12(22), 131-149. DOI:

MacQueen, K. M., McLellan, E., Kay, K., & Milstein, B. (1998). Codebook Development for Team-Based Qualitative Analysis. CAM Journal, 10(2), 31-36. DOI:

Matiza, T. (2022). Post-COVID-19 crisis travel behaviour: towards mitigating the effects of perceived risk. Journal of Tourism Futures, 8(1), 99-108. DOI: 10.1108/jtf-04-2020-0063

Md. Aris, N., Yusof, S. M., Idris, N. I. I., Zaidi, N. S., & Anuar, R. (2021). Analysis of firms’ characteristics affecting the sustainability reporting disclosure in Malaysia. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 11(14). DOI:

Mei, X. Y., & Lantai, T. (2018). Understanding travel constraints: An exploratory study of Mainland Chinese International Students (MCIS) in Norway. Tourism Management Perspectives, 28, 1-9. DOI:

Mirzaei, R., Sadin, M., & Pedram, M. (2023). Tourism and COVID-19: changes in travel patterns and tourists' behavior in Iran. Journal of Tourism Futures, 9(1), 49-61. DOI:

Nguyen, N. M., Pham, M. Q., & Pham, M. (2021). Public’s travel intention following COVID-19 pandemic constrained: A case study in Vietnam. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8(8), 181-189. DOI:

O'Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 160940691989922. DOI:

OECD. (2020). The territorial impact of COVID-19: Managing the crisis across levels of government. DOI:

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods (3 Ed.). SAGE Publications.

Saarijärvi, M., & Bratt, E.-L. (2021). When face-to-face interviews are not possible: tips and tricks for video, telephone, online chat, and email interviews in qualitative research. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 20(4), 392-396. DOI:

Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. SAGE.

Shah Alam, S., Masukujjaman, M., Omar, n. A., Mohamed Makhbul, Z. K., & Helmi Ali, M. (2023). Protection Motivation and Travel Intention after the COVID-19 Vaccination: Fear and Risk Perception. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 24(6), 930-956. DOI:

Shin, H., Nicolau, J. L., Kang, J., Sharma, A., & Lee, H. (2022). Travel decision determinants during and after COVID-19: The role of tourist trust, travel constraints, and attitudinal factors. Tourism Management, 88, 104428. DOI:

Siddharthan, R. (2014). Internal branding and new generation employees a.k.a the millennials. Research Journal of Science & IT Management, 3(12), 54-57.

Spalding, M., Burke, L., & Fyall, A. (2021). Covid-19: implications for nature and tourism. Anatolia, 32(1), 126-127. DOI:

Strauss, A. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge University Press.

Sutherland, A. E., Stickland, J., & Wee, B. (2020). Can video consultations replace face-to-face interviews? Palliative medicine and the Covid-19 pandemic: rapid review. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 10(3), 271-275. DOI:

Tang, K. H. D. (2022). Movement control as an effective measure against Covid-19 spread in Malaysia: an overview. Journal of Public Health, 30(3), 583-586. DOI:

Teeroovengadum, V., Seetanah, B., Bindah, E., Pooloo, A., & Veerasawmy, I. (2021). Minimising perceived travel risk in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic to boost travel and tourism. Tourism Review, 76(4), 910-928. DOI:

Tergu, C. T., Li, J., Azougagh, H., Tenya, A. W., Maddy, R. J., Acquah-Sampson, R., & Zhang, J. (2022). Perceptions of risks amidst COVID-19 on the youth’s domestic travel intentions in Ghana. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 10(04), 303-316. DOI:

Tie, Y. C., Birks, M., & Francis, K. (2019). Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Med, 7, 2050312118822927. DOI:

Tourism Malaysia. (2020). Survey on domestic travel in Malaysia. https://mytourismdata.tourism.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Domestic-Traveler-Survey-after-MCO-4.pdf

Tourism Malaysia. (2022). Malaysia tourism statistics in brief. https://www.tourism.gov.my/statistics

World Health Organization. (2022). Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/

Xie, L., & Ritchie, B. W. (2018). The motivation, constraint, behavior relationship: A holistic approach for understanding international student leisure travelers. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 25(1), 111-129. DOI:

Yang, Y., Cao, M., Cheng, L., Zhai, K., Zhao, X., & De Vos, J. (2021). Exploring the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and changes in travel behaviour: A qualitative study. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 11, 100450. DOI:

Yusof, A. (2021). Domestic travel still be the preferred choice for local travellers: Mavcom. New Straits Times. https://www.nst.com.my/business/2021/10/732668/domestic-travel-still-be-preferred-choice-local-travellers- mavcom

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

06 May 2024

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-132-4

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

133

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1110

Subjects

Marketing, retaining, entrepreneurship, management, digital marketing, social entrepreneurship

Cite this article as:

Aman, S. E., Azmi, N. F., & Sharkawi, S. (2024). COVID-19 and Travel Decision: A Qualitative Study on Malaysian Millennials. In A. K. Othman, M. K. B. A. Rahman, S. Noranee, N. A. R. Demong, & A. Mat (Eds.), Industry-Academia Linkages for Business Sustainability, vol 133. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 989-1000). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2024.05.81