Abstract

The research examines the development, implementation, and relevance and compares Section 17A of the MACC with developing and developed jurisdiction in the Malaysian corporate context. The study analyses the historical background of corporate liability and its effectiveness against corrupt practices in organizations. The research applied a qualitative methodology and adopted a jurisprudence approach, including the analyses of legislation and case laws. The study further compares the practices of countries like the United Kingdom and Indonesia. The study found that Sections 17A is unclear, and its application is limited. Therefore, the conviction rate of criminals involved in corruption is negligible. Further, the United Kingdom performs better in applying 7 equivalents to Section 17 A. Based on the findings, the study suggested to empower the investigative wing of MACC, a comprehensive and contemporary capacity-building program for the concerned authorities should be immediately launched to curb the menace. Ultimately, the government should improve the legal framework of corporate liability to yield significant results.

Keywords: Corruption, Corporate Liability, Section 17A

Introduction

The Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) defines corruption as collecting or giving any sort of remuneration or gratification in cash or anything of high value as a reward for obligations associated with their position (Balasingam & Rukumani, 2020). Corruption is defined as an evil plague that destroys society by weakening democracy and the supremacy of law, abusing human rights, lowering the standard of living, and fostering the rise of criminal organisations and other threats to humanity (Annan, 2003).

Malaysia is ranked 62nd out of 180 countries regarding public corruption (Transparency International, 2012). Malaysia's Transparency International Global Corruption Index score fell from 53 in 2019 to 51 in 2020 to 48 in 2021, dropping short of the 50-point threshold. According to Transparency International Malaysia, the drop in Malaysia's score may be due to the incapacity of previous and current administrations to battle corruption in politics and enhance its human rights records (Ayamany, 2022). Furthermore, it was said that another factor for Malaysia's lower ranking is its lack of political commitment to transform the MACC into a fully autonomous anti-corruption body.

It is further supported by the evidence that, as of April 2022, the MACC had initiated 379 investigative papers, with 425 persons jailed for corruption (Bernama, 2022). Companies like the Port Klang Free Zone (PKFZ), the Sabah Water Department, Malaysia International Shipping Corp Bhd (MISC), and the particularly recent 1MDB scandal indicate how the corruption disease has spread like wildfire in the Malaysian business environment (Anjum, 2020). As organisations grow more susceptible to misleading and corrupt practices, the issue of whether the liability placed on individuals for corruption accusations may be extended to corporations arises.

A recent shift to the MACC Act, in 2020, to include Section 17A, is seen as a pathfinder in allowing corporations to be charged and punished in court, despite without removing the rapidly encircling corruption plaque. Forming this section by our government is a positive step towards satisfying its obligations of being a signatory to the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) (Aik & Ching, 2020). This provision aims to establish a clean business environment and hold corporations accountable for unethical practices within the enterprise.

Pristine Offshore Sdn Bhd (Pristine) was the initial corporation accused under this clause of bribing Mazrin Ramli, the COO of Deleum Primera Sdn Bhd, so as for Pristine to gain a subcontract from Petronas Carigali (Shiu et al., 2021). Chew Ben Ben, Pristine's prior director, was also charged with proposing a bribe under MACC Act clause 16(b), a broad provision that allows the prosecution of anybody who promises, receives, or offers any sort of incentive. Section 17A permits Pristine Offshore, for example, to be treated as an independent legal person in its own right. Pristine, on the other hand, is the only case charged under Section 17A, because it comes into force in 2020 (Yatim, 2021). According to the news item, the hearing date has yet to be decided because the case is still being handled by Yang Arif Puan Rozilah Salleh, the Sessions Court Judge. The case is presently being managed to ensure that all files and information have been collected before the hearing.

The problem is that since Section 17A was adopted in 2020, just one corporation has been penalised in court. Is Section 17A truly a toothless tiger? For starters, the regulatory framework of Article 17A is faulty since it only applies to corrupt suppliers; this provision does not protect bribe receivers. The second consideration is Section 17A's 'escape route' or'safety net' for businesses guilty of fraud or corrupt practises. According to Section 17A (4), a company's defence is to show that it has 'adequate processes' in place. What is a sufficient measure? Section 17A (5) of the MACC Act states what a firm may demonstrate to demonstrate that 'adequate processes' are in place within their organisation and to absolve themselves of liability. This section further states that such directives will be distributed by the Prime Minister's Department.

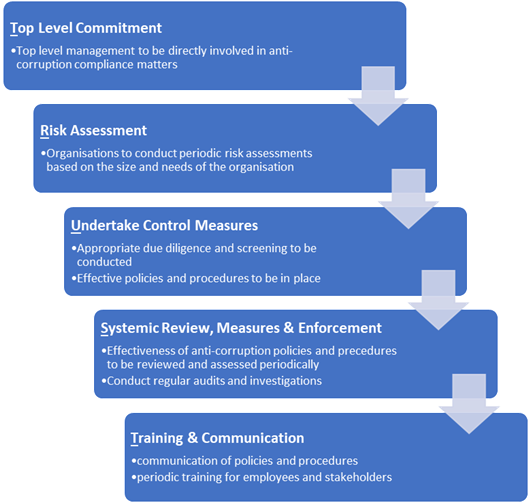

Figure 1 shows the Minister's instructions based on the idea, often known as T.R.U.S.T. It should be noted that these regulations are not exhaustive, and a company can go further to demonstrate that 'adequate mechanisms' are in place to prevent fraud within the enterprise.

The problem of determining the 'adequacy' of such techniques develops. Is it sufficient to have such 'proper' policies in place without investigating how practical or effective these actions are in combating fraud in a commercial organisation? Another concern is that Section 17A does not address the consequences of failing to implement suitable organisational processes, nor does it clarify whether such failure comprises a crime.

Section 17A makes no provision for establishing the adequacy of such measures. As a consequence, enterprises are only required to perform the 'bare minimum' in order showing that proper procedures are in place inside their company, and they will be 'off the hook' in no time. Furthermore, the fines levied under Section 17A (2) are insufficient to punish violators because they have no direct impact on businesses. Section 17A (2) states that firms must be fined 10 times the value or quantity of the prize, or RM one million, which is larger, or imprisonment for a term not exceeding twenty years, or both.

In contrast, the Companies Act of 2016 states that any business person, particularly the firm's secretary or directors, might be imprisoned on behalf of the corporation, how does such a penalty affect the organisation? How is a company imprisoned? Is it enough for firms to pay penalties and be released'? Following that, flaws in corporate fraud disclosure strategies include flaws in whistleblowing protocols and a lack of whistleblower security. It explains why companies are charged in Section 17A instances in such small numbers. Section 17A of the MACC is riddled with issues and obstacles. As a result, this research aims to look at such issues and give recommendations on overcoming the challenges that Section 17A encounters while prosecuting firms.

As a result, this research aims to look at the performance, relevance, and concerns surrounding the use of Section 17 A. The paper also compares it to other established and growing countries, for example the United Kingdom and Indonesia. Finally, the scope of corporate criminal culpability; nonetheless, the study concentrates mainly on fraud and unethical practices. This paper presents recommendations based on careful analysis that might be applied to resurrect the prosecution powers granted under Section 17A. This study adds significantly to the body of knowledge. It offers light on the issues related with Section 17 A compliance.

Literature Review

Bribery as well as corruption scandals in the Malaysian corporate environment are investigated and reported on. The MACC website provides annual data on MACC charges over time. According to the data, 998 charges were made in 2020, 851 charges were made in 2021, and 652 arrests were made in 2022. Although many people feel that a decrease in the number of charges signifies a substantial step towards making the country corruption-free, this is not the case. Malaysia has a 'sorry' corruption rate, according to the 2021 Transparency International Global Corruption Index. However, the overall number of arrests made does not equate to the actual number of arrests made by MACC officers.

The number of corporations involved in corruption scandals has grown dramatically over the years, such as the well-known Tabung Haji shortfall in 2017, the Immigration Department's scandal on the country's migration systems in 2016, the Port Klang Free Zone cargo controversy in 2008, the Sabah Water Department fraud examine in 2015, and the most significant business scandal so far, the 1MDB scandal, which was indeed an astonishing tale of power abuse.

Considering the complexities of both domestic and international corruption challenges, MACC Chief Datuk Seri Azam Baki suggested that anti-corruption agencies should be more proactive (Koya, 2020). He remarked that as the country's economic climate has evolved, so has the manner of operation in corruption. As a result, the MACC's investigative method, called an intelligence-based probe, has become more proactive. He further claimed that corruption had spread beyond Malaysian borders, citing the high-profile cases of 1MDB and SRC International Sdn Bhd. Therefore, Azam Baki remarked that one of the primary reasons for the critical need for regulation requiring corporate responsibility, that is how Section 17A of the MACC has been implemented, is the continually altering mode of operation in instances involving corruption. This clause permits companies to be held responsible for the acts of any persons associated with them who are found to be involved in corruption, and it helps the MACC stay 'on par' with evolving corruption classifications within the Malaysian corporate sector. According to Kana (2020), introducing Section 17A of the MACC is an excellent stride forward in the country's fight against corruption. This provision would make the organisation and its directors personally liable if anybody associated with the organisation, such as employees or third-party subcontractors, engaged in corrupt actions for the advantage of the organisation.

According to Anjum (2020), corruption results in both the distortion of the law and the deterioration of the institutional framework. According to Mallow (2018), corruption has an influence on individuals, organisations, society, the economy, and the nation as a whole. Corruption raises the cost of life and increases the price of products and services. Such pressure would drive individuals or businesses to engage in corrupt activities in order to supplement their revenue. This generates an endless vicious cycle in which corruption breeds corruption. It transforms into a vortex that 'sucks the life energy out of a country,' causing it to be more vulnerable to criminal acts and destroying its democratic principles and legal laws. Business corruption would also slow the growth of the business environment. Organisations, for example, might engage in corrupt and bribery practises to gain contracts or other types of satisfaction in a business environment.There could be less competition in the corporate sector as a result of such training, and 'greedy' firms would seek to degrade the worth of what they offer while charging a higher price since there is no rivalry to test their authority in the corporate market.

In his remarks in 2014, ex-Deputy Solicitor General YBhg Datuk Tun Abd Majid stated that the notion of CCL derives from the idea that an organisation has a different legal existence from its workers, executives, and even those who own it (Hamzah et al., 2014). This method allowed a firm to shield its employees from criminal prosecution. Majid went on to argue that historically, a company may be held liable for its employees' activities in two ways: identity and indirect liability. Companies are liable under the identification principle if the individual doing the corrupt act is viewed as the corporation's power and mind. Assuming the workers behaved within the corporation's authority and control, the corporation would be held liable under the fictitious liability idea. However, these principles were formed through case law, and no appropriate statute exists to 'solidify' the CCL principle. Section 17A is the first corporate responsibility law to be codified.

Cynthia Gabriel, a Human Rights Advocate of the Centre to Combat Corruption and Cronyism, or C4, indicated that Section 17A was never formed by accident and that the scheme was designed after Section 7 of the UKBA 2010 (Lynn & Ganesan, 2021). Cynthia stated that financial fraud was spreading like wildfire and had "gotten out of hand," and she added that corruption prevention companies required the authority to hold corporate entities liable for corrupt practices committed within the organisation.

Cynthia also stated that Section 17A was enacted to nullify and minimise the 'corporate veil principle,' which has historically been applied by company directors to defend themselves from corruption charges brought directly against them, and that such directors or top management could avoid fraud charges by simply paying a fine. In response to the lately set up Section 17A provision, a commercial organisation, as well as individuals associated with the organisation, such as directors, secretaries, top management, or even its agents, may be grasped liable for fraudulent conduct such as supplying a bribe or any other form of gratification within the organisation or for the benefit of an organisation.

It claims that Section 17A broadens its reach such that not only huge corporations, but even small privately owned corporations, law firms, and even partnerships, may be held liable for fraud under this section. This section assures that, regardless of an organization's size, if it has engaged or 'housed' illegal actions within its boundaries, it will be held accountable and punished in court under paragraph 17A. Cynthia applauds Section 17A's "sweeping powers," as fraud or nepotism will now be traceable in any area and at any tier of a firm, as businesses will be more "alert" to the organization's activities at the most basic level. It also examines a strict liability charge in which an entity's only defence is to show that it has 'sufficient' anti-corruption practices. As a consequence, organisations must develop efficient ways to combat corruption rather than returning to the "blame game" or "I was unaware game" if tried in court.

Research Methodology

The research focuses on Section 17A's regulatory structure and its efficacy. The paper then contrasts how firms were brought up in trial prior to and following Section 17A was implemented. The paper covers Section 17A's efficacy before addressing the concerns and obstacles that Section 17A has experienced since its implementation in 2020. The researcher will determine why just one corporation has been prosecuted under Section 17A through her study and discussions with relevant authorities (Low & Low, 2021). Based on Low and Low (2021), the researcher would draw conclusions about the concerns and obstacles experienced by Section 17A as contrasted to those encountered by Section 7 of the UK Bribery Act when it was enacted in the UK.

It also involves a jurisprudential examination to evaluate norms, rules, and guidelines. In this study environment, the jurisprudential aspect comprises a critical review of current laws, rules, and policies.

Findings and Analysis

ISSUES AND DIFFICULTIES IN APPLYING SECTION 17A government-owned, should be handled uniformly under the law, and no 'passes' should be given to entities linked with particular political parties or agendas.

Section 17A of the MACC became law in 2020, but the spread of the covid-19 virus complicated its application. That's why the MACC is giving businesses more time to prove they've had good internal controls in place to thwart fraud. However, some companies are unaware of such regulations, and many organisations lack the anti-corruption safeguards that are necessary to protect themselves from internal corruption. Seminars and MACC attempts to educate the public on how Section 17A can be used to prosecute instances of corruption and bribery are scarce.

After then, businesses aren't sure if their anti-corruption procedures and practises are'sufficient' to rely on the Section 17A defence. It is unfair to hold all businesses to the same high standard when larger, more profitable businesses can afford to invest more in anti-corruption controls and procedures. It is unfair for the MACC to apply such standards to tiny businesses, especially in the midst of a global pandemic that has wreaked havoc on businesses of all sizes.

Therefore, it is suggested that enterprises be subject to varying requirements depending on their size and the nature of their operations. It ensures that struggling firms won't be burdened with additional responsibilities and pressures. From the eyes of a practising attorney The MACC can investigate and respond to any complaints of wrongdoing. However, the MACC lacks the power to file criminal charges against an individual or a company. According to Section 7 of the MACC Act, the commission's officials do not have the authority to levy fees. According to Section 8 of the same statute, once the MACC officers had reviewed the case, they would "pass over" the subject to the proper authorities for prosecution.

As such, it is seen as a barrier that lessens the impact of the recently formed Section 17A. An organisation cannot be prosecuted, for instance, even when the MACC has conducted extensive investigations into how fraud occurred within the company and the many technologies employed to discover it. Such investigating personnel would be more suited in the prosecution phase, but this limits the powers assigned to the MACC, which should be an autonomous agency with the capacity to conduct a whole trial as necessary. Wan Hashim and Mohamed (2019) state that new authority is being granted to the UK's anti-corruption institution, the Serious Fraud Office.

There is no need to involve any other groups in the prosecution of this case. The Serious Fraud Office's autonomy from external actors is further strengthened by this. However, once the MACC officer in a country like Malaysia has finished their investigation, they would submit their findings to the Attorney General to get the green light to prosecute the offender. The Attorney General of Malaysia has broad discretionary powers to commence or continue legal proceedings, as stated in Article 145(3) of the Federal Constitution. The Attorney General's authority is absolute and cannot be contested.

Since the president appoints the position of attorney general, there is always the possibility that neither the government nor publicly held corporations will face legal action, or that the attorney general may recuse themselves because of the president's personal stake in the outcome. After that point, the MACC is no longer seen as an autonomous entity with free will. Wan Hashim and Mohamed claim that the executive branch of government selected the specialised panel for fraud and the advisory board that is supposed to oversee the MACC. If the government itself appoints the committees that investigate allegations against government-affiliated organisations, there will be inherent bias. There could also be a conflict of interest, in which case the committees would be prevented from taking any additional action to protect the interests of the government that had chosen them.

Even more so, it is clear from Section 17A that the burden of proof has been moved to the corporation to show that they have 'sufficient' policies and practises in place to avoid prosecution under Section 17A. But, as was already mentioned, there is no' sufficient' procedural criterion in Section 17A. How do we know if this policy is working? Alternatively, would there be external organisations in place to 'audit' or 'evaluate' the efficacy of the same, or would internal reports of corruption serve as a proxy?

Second, it can be difficult to prove that your organisation has "sufficient" anti-corruption policies in place. It is not clear whether the burden of proof would be on the firm to prove its defence beyond a reasonable doubt or on the balance of probabilities. To ensure that businesses do not get off so easily by demonstrating the bare minimum, it is proposed that an additional degree of proof, beyond reasonable doubt, be placed on them. Companies should be required to provide evidence of their anti-corruption efforts beyond any reasonable doubt, and no questions or investigations should be permitted into their procedures in this area. It strikes fear into the hearts of institutions, ensuring that they take comprehensive, foolproof safeguards against corruption.

INNOVATIONS IN OTHER COUNTRIES

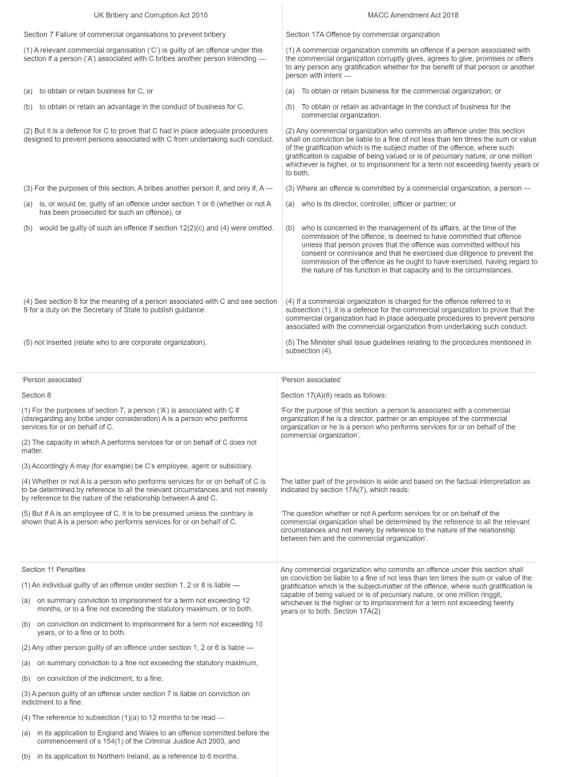

Since Section 17A was modelled after Section 7 of the UK Bribery Act, the investigation focuses on the United Kingdom's tactics. The two provisions share a similar structure, nevertheless, there are some important differences as reported in figure 2:

Comparison of UK Bribery and Corruption Act 2010 and MACC Amendment Act 2018

Section 17A (1) of the MACC is clearly related to Section 7 of the UKBA, while Section 17A(4) of the MACC is identical to Section 7(2) of the UKBA. Under Section 7(3) of the UKBA, a company can be prosecuted for an offence even if no individuals have been found guilty of the same. When trying to figure out who falls within the definition of "linked with a corporate organisation," the UKBA requires that Section 7(4) be read in conjunction with Sections 8 and 9. Contrary to common assumption, Section 17A of the MACC adequately and clearly describes who can be associated with a corporation.

The second key distinction is the punishments that are mandated by each law. The UKBA imposes different sanctions on individuals and businesses due to the fact that they are two separate legal entities. The MACC Act imposes the same penalties on both individuals and corporations. The MACC Act allows for life sentences of up to 20 years in jail, while the UKBA does not. It's interesting to contemplate the potential consequences of the MACC Act for businesses.

A 'deeming liability' clause with dual liability is another way in which the MACC Act diverges from the UKBA model. The first time this happens is when a company is accused of committing a corrupt act and has no effective anti-corruption practices to back up its claims. The second tenet is an individual liability; if a company is found guilty, its partners, controllers, executives, and top management are individually liable under Section 17A. The MACC's plan guarantees that top executives will have no recourse to the "corporate veil" defence in the event of legal action being taken against the company. Additionally, it ensures that bribery and corruption are prioritised as serious issues within a company.

The UKBA does not have deeming provisions because criminal liability is established through two separate violations. Companies can be held liable for acts of corruption and bribery committed inside their own ranks if they fail to take adequate preventative measures. Those at the top of an organisation who are found to have participated in corrupt activities may be held personally responsible for their actions. Under the MACC, these violations are combined to create a presumption of guilt against a company and its upper-level executives (Kotler et al., 2018). The US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act was used by Malaysian lawmakers as an example of a law that regulates the actions of American businesses that bribe foreign officials to win or keep business An organisation can invoke this provision if it can be shown that the provision of such a type of pleasure is intended to maintain or increase the company's clientele. Once the motivation is known, the corporation's activities will be deemed unlawful.

The MACC has taken a similar approach, extending Section 17A's jurisdiction to hold people or foreign businesses accountable for corrupt activities. It empowers the MACC to conduct investigations outside Malaysia's boundaries. For example, if a Malaysian business, such as 1MDB, undertakes corrupt activities abroad, it is still responsible per Section 17A of the MACC.

Discussion and Recommendations

RECOMMENDATIONS TO BE THOUGHT ABOUT

The first step is a proposal to give the MACC and its officials prosecutorial powers so that it can function as a legitimate administrative agency in its own right. There will be no interference with the MACC's charges, and the MACC's investigation will be conducted properly "from womb to tomb." The MACC's investigative powers are enhanced by its ability to bring criminal charges, making it better able to promote an anti-corruption culture in the business world.

After that, it's suggested that different governments join forces to combat corruption in the corporate world. Although the MACC must remain impartial, it is essential that it collaborate with other agencies to combat corporate fraud. These agencies include the Securities Commission Malaysia, the Companies Commission Malaysia, Cybersecurity Malaysia, the Inland Revenue Board, Bank Negara Malaysia, and the National Anti-Financial Crime Centre. The MACC is able to gather more proof that the corporation engaged in corrupt practises inside its own ranks by coordinating with other authorities and collecting new evidence. It also gives the MACC the staff it needs to investigate more thoroughly, including responding to requests from other bodies. The following guidance applies to the fine imposed on businesses under Section 17A.

The maximum punishment under Section 17A is RM 1 million, or 10 times the value of the gratification given or received. According to Section 17A, the maximum sentence for such companies or individuals is 20 years in prison. It's a step in the right direction towards making sure companies and their employees pay a steep price if they try to bribe their way to success. However, the consequences are ineffective because they just involve fines, which do not prevent other businesses from following in the same corrupt footsteps as the sanctioned ones.

To show that Malaysian laws do not tolerate any form of corruption, the current MACC commissioner has proposed that entities found culpable according to the Section 17A provision be included as outlawed by the Bursa Malaysia share market for a set period of time or even be barred from government-related contracts (Chang, 2019). It would send a message to other companies that if they engage in any kind of activity, they risk losing money and, even worse, their standing in the marketplace.

The following recommendations are made for a variety of standards applied to businesses on the efficacy of anti-corruption initiatives and plans. It's unfair to make small businesses foot the bill for better rules that larger companies can afford to implement thanks to their greater size and greater resources. would be helpful if you decrease the burden put on small enterprises because their organisations are smaller and lack the capacity to adopt costly anticorruption strategies.

The remainder of the guidance focuses on the evidence threshold at which a defence must be demonstrated by an organisation. As was previously mentioned, Section 17A reverses the burden of proof from the government to the group under investigation. Companies should bear a heavier burden to prove their innocence under the 'beyond reasonable doubt' standard because corruption claims have become so pervasive in the business world. It ensures that businesses have the means at their disposal to defend themselves in the event that any individual associated with the company is accused of engaging in corrupt or bribery practises.

Deferred Prosecution Agreements (DPAs) are also employed in the United Kingdom, thus the MACC should adopt this strategy. Schedule 17 of the Crime and Courts Act 2013 (Serious Fraud Office) created DPA in the United Kingdom in 2014, where it has since been adopted and applied. Companies and anti-corruption groups might negotiate an agreement through a Deferred Prosecution Agreement (DPA). If the company complies with the terms of the agreement, it won't face legal action, and any proceedings already underway will be promptly halted.

Because DPAs eliminate the need for lengthy and expensive trials, they are often favoured. Additionally, it permits a company to "make do" with the damage by fixing all anti-corruption procedures. For the simple reason that it has been claimed that collateral sanctions or damages would not only drive a company to bankruptcy but also cause the loss of employment for completely innocent people. The parties may agree to a condition in which the corporation pays a fine that is less severe than the maximum fine allowed by Section 17A.

Its goal is to ensure that the company admits that bribery and corruption took place within its walls. One example of a stipulation is requiring an organisation to improve its internal controls and processes to reduce fraud and corruption.

The first trial in the United Kingdom took place nearly two years after the DPA was enacted. In this case, Stanbic Bank Tanzania, a former subsidiary of Standard Bank, paid ICBC Standard Bank $6 million. It was speculated that the 2013 payment to a local partner, Enterprise Growth Market Advisors, was intended to encourage the Tanzanian government to approve the bank's proposal for a private placement on its behalf.

After conducting their own probes, Standard Bank reported their accusations of a bribe to the Serious Fraud Office, a government agency with the express mission of examining charges of corruption. In this DPA, Standard Bank agreed to pay $25.2 million to UK authorities in exchange for allowing the Tanzanian government to collect nearly $7 million in compensation and interest. In addition, the bank agreed to reimburse the SFO for £330,000 in expenses incurred while the SFO investigated the bank for possible instances of misconduct.

The bank also agreed to pay for the cost of updating its anti-bribery and corruption policies, controls, and processes, as well as its compliance and fraud-detection systems.

After the bank cooperated with authorities to evaluate and investigate its anti-corruption policies, procedures, and processes, the fines were reduced. This raises the issue of how to put such a theory into practise in Malaysia. Is it true that this idea holds true in a country in Asia? Mulyana (2021) discussed the potential application of DPAs in Indonesian criminal law. The cultures of Malaysia and Indonesia are remarkably similar; as close neighbours, they share many values and traditions. According to Mulyana (2021) the DPA model might be quickly applied in Indonesia because the country adheres to the opportunity principle, which recognises the prosecutor as the case monarch.

The Attorney General (also known as the public prosecutor) in Indonesia has the discretion to either drop or continue a case based on the opportunity principle. A DPA is suggested to be entered into between the prosecutor and the company, with judicial oversight. Mulyana (2021) stated that a DPA may be offered by regulators or prosecutors when it is clear that the company is willing to cooperate throughout the investigation process, such as admitting that certain violations were committed, agreeing to pay compensation or fines, or agreeing to hire independent auditors to oversee and track the activities of an organisation for a set period of time. Mulyana (2021) suggested that Indonesia's DPA model be well thought out and built. The DPA model should be kept under 'check and balance' by external regulators at all times. It ensures that no biases exist and that law enforcement's authority is not questioned while they implement a DPA.

The study claims that the criteria established in the DPA would be made public and properly accounted for. Legal action may be taken against the group if it breaches the DPA, hence a warning to that effect should be given. Instead of eliminating or dismissing the procedure altogether, DPA just delays it. More stringent regulations should be in place to ensure that businesses have abided by the DPA. It should also be recommended that the DPA only apply to corporations, not individual employees. This means that individuals associated with a company can be sued for corrupt practices even after it has entered into a DPA.

According to Mulyana (2021), there are two levels of analysis required for a DPA to be enforced: evidence, and beneath the evidence level, establishing whether or not the corporation actually committed wrongdoing. At the public interest stage, the prosecutor weighs the public's interest in the matter against the seriousness of the corporation's conduct. After reviewing both sets of evidence, the authorities or prosecutor decide whether or not to grant the Organisation a DPA.

Therefore, DPA is recommended for use in the Malaysian context since it facilitates settlements that are both speedy and economical. Since DPA agreements only impose penalties and limits on firms to adhere to promote more effective anti-corruption policies and principles in the organisation, courts may use the DPA mechanism to ensure that innocent parties do not become victims in the aforementioned situation. The DPA concept also supposedly allows for a "quicker settlement" because it is harder for the prosecution to prove that a company "fostered" an act of corruption within an organisation.

Conclusion

By carefully examining the merits and shortcomings of Section 17A, it is evident that Malaysia has made the right decision in adopting the principles of corporate responsibility articulated in the FCPA and the UKBA. Courts can now hold corporations and their top executives liable for any bribery or corruption that occurs inside their own ranks thanks to Section 17A. The 'corruption virus' is spreading like wildfire across the Malaysian corporate community, but Section 17A gives the government the tools it needs to stop it. When it comes to avoiding criminal acts of corruption in the business environment, Section 17A ensures that a 'check and balance' principle exists between organisations and authorities like the MACC, the Attorney General, or the public prosecutor.

Because of this shift, companies are now responsible for proving that they have adequate anti-bribery and anti-corruption practises and policies in place, which should make it easier for public prosecutors to prove that a company engaged in corrupt behaviour.

References

Aik, G. K., & Ching, L. S. (2020). Origin of Section 17A of MACC Act: Lessons from the UK Experience. GanPartnership. https://www.ganlaw.my/section-17a-macc-act-what-are-the-lessons-learnt-from-foreign-case-studies/

Anjum, Z. (2020). Major Bribery and Corruption Cases in Malaysia. Anti-Bribery Anti-Corruption Center of Excellence. https://abacgroup.com/major-bribery-corruption-cases-in-malaysia-abac-policies-offer-solutions/

Annan, K. (2003). Statement on the Adoption by the General Assembly of the United Nations Convention Against Corruption. In United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/treaties/CAC/background/secretary-general-speech.html

Ayamany, K. (2022). Malaysia drops again in world corruption ladder, scoring below 50 for first time in nine years. Malay Mail. https://malaysia.news.yahoo.com/malaysia-drops-again-world-corruption-084053450.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAEUL-t28aJFnhxSSrUN8AH1Su6Wv0DApzNttFT630mBPXTHqgiTbOTOY5nPSVwkzCQIRW-ZFkGkVPsYgJWyUTs5zC

Balasingam, U., & Rukumani, V. (2020). Section 17A of the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Act 2009: Corporate Liability and Beyond. Malayan Law Journal, 4. https://advance.lexis.com/api/permalink/c2a728af-1b1a-4e84-a908-%0Ae8f21a85759d/?context=1522468%0A

Bernama. (2022). MACC opens 379 investigation papers, arrest 425 individuals as of April. https://bernama.com/en/crime_courts/news.php?id=2084050

Chang, S. (2019, July 2). Section 17A of the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission Act 2009. Business Today. https://www.businesstoday.com.my/2019/07/02/section-17a-of-the-malaysian-anticorruption-%0Acommission-act-2009/%0A

Hamzah, Z. L., Syed Alwi, S. F., & Othman, M. N. (2014). Designing corporate brand experience in an online context: A qualitative insight. Journal of Business Research, 67(11), 2299-2310. DOI:

Kana, G. (2020, February 8). Corporate Malaysia: Waging War on Corruption. The Star. https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2020/02/08/corporate-malaysiawaging-%0Awar-on-corruption%0A

Kotler, P., Keller, K. L., Ang, S. H., Tan, C. T., & Leong, S. M. (2018). Marketing management: an Asian perspective. London: Pearson.

Koya, Z. (2020, October 10). We must be proactive as corruption cases getting more complex, says MACC chief. The Star. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2020/10/10/we-must-be-proactive-ascorruption-%0Acases-getting-more-complex-says-macc-chief%0A

Low, C. K., & Low, T. Y. (2021). ). Corporate Criminal Liability and Section 17A of the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission Act. Singapore Academy of Law Journal. https://deliverypdf.ssrn.com/delivery.php?ID=97902100406908908209410108402008%0A910710109204608401203207308306902811802800708309603104209810704211602%0A905306711109109609000407701702000500105906807700008202308700406306601%0A1113075030095027072112067085025

Lynn, L. C., & Ganesan, L. (2021). New Macc Act for Corruption used for the First Time. BFM: The Business Station. BFM: The Business Station. https://bfm.my/podcast/evening-edition/evening-edition/new-macc-act-for-corruptionused-%0Afor-first-time#.YFSvlQWTZKM.twitter%0A

Mallow, M. S. (2018). Corruption: The Law and Challenges in Malaysia. ADVED 2018- 4th Internationa; Conference on Advances in Education and Social Sciences, Turkey. https://www.ocerints.org/adved18_e-publication/papers/22.pdf

Mulyana, A. N. (2021). Deferred Prosecution Agreement (Dpa) Concept In The System Of Criminal Jurisdiction In Indonesia. Webology. https://webology.org/datacms/%0Aarticles/20220328104422pmwebology18(6)-292pdf.pdf%0A

Shiu, R.-F., Gong, G.-C., Fang, M.-D., Chow, C.-H., & Chin, W.-C. (2021). Marine microplastics in the surface waters of "pristine" Kuroshio. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 172, 112808. DOI:

Transparency International. (2012). Corruption Perception Index. Retrieved on 23 of September 2023, from https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2012

Wan Hashim, W. M., & Mohamed, M. (2019). Combating corruption in Malaysia: an analysis of the Anti-Corruption Commission Act 2009 with special reference to legal enforcement body. Journal of Administrative Science, 16(2), 11-26.

Yatim, H. (2021, August 4). Oct 11 fixed for case management in corporate liability case involving Pristine Offshore. The Edge Markets. https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/oct-11-fixed-case-management-corporateliability-%0Acase-involving-pristine-offshore%0A

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

15 November 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-130-0

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

131

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1281

Subjects

Technology advancement, humanities, management, sustainability, business

Cite this article as:

Mohamed, N., Gnanasegaran, A. A. K., Sultan, N., Husin, S. J. M., & Perwitasari, W. (2023). Section 17A of the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Act: The Corporate Implementation Perspectives. In J. Said, D. Daud, N. Erum, N. B. Zakaria, S. Zolkaflil, & N. Yahya (Eds.), Building a Sustainable Future: Fostering Synergy Between Technology, Business and Humanity, vol 131. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 809-822). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2023.11.67