Cultivating Sustainable Performance: A Framework for Governance Indicators in Village Owned Enterprises

Abstract

Village owned enterprises have emerged as vital instruments of economic revival and rural welfare enhancement in Indonesia. Their strategic significance has attracted widespread attention, yet the absence of standardized governance mechanisms has left these organizations vulnerable to fraud. This conceptual paper addresses this critical gap by embarking on a preliminary exploration of governance indicators. Drawing from principles such as professionalism, openness, responsibility, participation, localization, and sustainability, this study lays the foundation for comprehensive governance frameworks within village owned enterprises. The paper signifies a pivotal step toward the development of governance indicators, facilitating the attainment of village owned enterprises objectives and fostering sustainable rural development in Indonesia. This inclusive approach ensures that these indicators are not only rooted in sound theoretical foundations but are also sensitive to the practical intricacies and diverse perspectives that shape governance in this dynamic and culturally rich nation. By scrutinizing the understanding of professionalism, openness, responsibility, participation, localization, and sustainability, this paper not only contributes to the academic discourse but also offers practical guidance for stakeholders striving to ensure the effective governance of village owned enterprises in Indonesia. Future research endeavors must prioritize the development and implementation of tailored governance indicators suited to the nuanced needs of VOEs. Collaborative focus group discussions, engaging government officials, stakeholders, academics, and relevant actors, are indispensable in crafting the framework of governance indicators

Keywords: Good Governance, Indonesia, Social Enterprises, Village Owned Enterprises

Introduction

Social enterprises have recently become the concern of many governments in the world to help them solve the social problems and economic difficulties they experience (Khan et al., 2021; Poledrini & Tortia, 2020). This is caused by the government's declining ability to solve social problems (Dey & Teasdale, 2013). In addition, the government also expects the community to be able to play an active role in solving social and economic problems (Powell et al., 2019). This makes the growth of social enterprise organizations increase in various countries in Europe, Asia, Africa, and America (Ahmad Nadzri et al., 2021; Johari et al., 2020; Spear et al., 2007; Sari et al., 2021; Tausl Prochazkova & Noskova, 2020; United Nations, 2020; van Twuijver et al., 2020). Especially in Asia, the growth of social organizations exceeds one million organizations (British Council, 2021).

In Indonesia, Village Owned Enterprises (VOE) have garnered significant attention from various stakeholders. VOE represents a distinct category of business entities, where the village government holds partial or full ownership of the capital. The legal foundation for the establishment of VOEs by village governments is rooted in Law (UU) Number 6 of 2014. The primary objective behind the creation of VOEs is the judicious management of village assets. They achieve this by offering services and engaging in diverse business activities, all aimed at enhancing community well-being and bolstering the village's financial resources, as substantiated by previous research (Fuadi et al., 2022; Sari et al., 2021). This dual mandate underscores the multifaceted nature of VOEs, categorizing them as both economic enterprises and social organizations within the Indonesian socio-economic landscape (Sari et al., 2021).

To ensure the sustainability of its organization, VOE must pay attention to good governance practices (Sari et al., 2022). The importance of good governance practices at VOE has been explained in Government Regulation (PP) Number 11 of 2021. The existence of good governance at VOE can have an impact on VOE performance. As suggested by (Sengupta & Sahay, 2017) if governance in social enterprise organizations goes well, then legitimacy, accountability, and transparency in organizational management will be achieved. In addition, good governance will result in management compliance with applicable laws, transparency, and organizational effectiveness (Cornforth, 2012; Farmer et al., 2016). When good governance practices go well, organizational performance will also be good (Kurnianto & Iswanu, 2021; Larner & Mason, 2014).

At this time, the application of good governance in VOE still does not have a strong "structure". There is still "confusion" about how the right concept of good governance can be applied to VOE. Widiastuti et al. (2019) have tried to formulate governance indicators for VOE based on six principles. However, after the indicator was run on VOE, it was found that the indicators were too complex to be applied. On the other hand, good governance at VOE is needed to overcome the fraud that often occurs (Suryanto et al., 2020) and to ensure VOE performance is in line with expectations (Sari et al., 2022). Therefore, a preliminary study is needed regarding the concept of good governance at VOE in Indonesia.

Due to its distinctive nature as a social organization, Village Owned Enterprises (VOE) diverge significantly from conventional corporate entities, resulting in variations in governance principles (Singh & Rastogi, 2023). These distinctions arise from differences in organizational objectives and the nature of activities undertaken by VOEs, setting them apart from typical commercial enterprises. Notably, the Government of Indonesia has laid down a comprehensive framework for VOE governance in Government Regulation Number 11 of 2022. This framework is underpinned by five fundamental principles: professionalism, transparency, accountability, community participation, emphasis on local resources, and sustainability. Notably, these principles encompass unique elements specific to VOEs, such as the imperative to leverage the village's inherent resources. The presence of these specific governance nuances warrants in-depth exploration within the context of effective governance in VOEs.

This study attempts to elucidate the foundational concept of good governance in VOEs through an extensive literature review, establishing a connection with the regulatory framework outlined in Indonesian Government Regulation Number 11 of 2021. Furthermore, it aims to identify potential avenues for future research pertaining to governance in VOEs. Beyond the academic realm, this research offers practical value by furnishing VOE Directors with a valuable guide for implementing sound governance practices within the VOEs they oversee, thus contributing to the overall enhancement of VOE operations and their role in advancing rural development.

Village Owned Enterprises (VOE)

VOE as social organization

Referring to Law 06 of 2014, the definition of a VOE is a business entity owned by the village with equity participation, either in large part or as a whole. The purpose of establishing VOE is to manage village assets, do business, and carry out services that will later be intended for the welfare of the village community. The Peraturan Menteri Sesa Regulation 2014 specifically explained the purpose of establishing a VOE, namely as an effort to accommodate all activities in the economic sector or public services managed by the village or collaboration between villages. However, the meaning of VOE is growing with the issuance of Government Regulation Number 11 of 2021. In the latest regulations, VOE has been recognized as a legal entity whose source of capital can come from just one village or from several villages. So, at this time, there are terms VOE and joint VOE. PP 11 of 2021 also regulates how operating companies can be run by VOE. VOE can be the executor of the business being run, or VOE can be the parent company for business units with legal entities. It is hoped that the clearer legal position of the VOE will have an impact on its development and performance.

In the late 1890s, the idea of social entrepreneurship initially came into existence in Italy (Defourny & Nyssens, 2008) later, it became popular among researchers and practitioners in other nations in Europe and the United States. However, the worldwide literature has not used a uniform definition of social enterprise (Dart, 2004). According to several academic studies (Seelos & Mair, 2005; Sari et al., 2021) social enterprises are businesses that seek to address social issues in novel and self-sufficient ways. Although these groups have existed for many years, the phrase "social enterprise" has just recently been used in academia (Bacq & Eddleston, 2018; Dart, 2004; Waddock & Post, 1991; Yunus et al., 2010).

Referring to the existing literature, VOE can be categorized into social enterprise organizations that have dual goals. This is stated in government regulation number 11 of 2021 as follows:

“a legal entity established by the village or in cooperation with the village to oversee businesses, use resources, promote investment and productivity, provide services, or operate different sorts of businesses for the good of the community as a whole”

From the explanation of the regulations above, it can be concluded that VOE is a business organization established with the aim of managing the wealth that belongs to the village with the aim of improving the welfare of the people in the village. This became the basis for establishing VOE as a social enterprise organization.

The Development of VOE

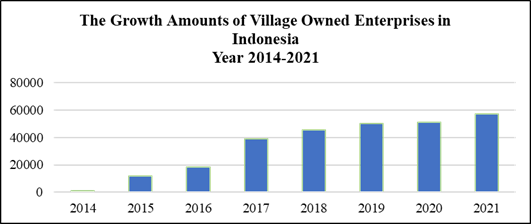

The proliferation of Village Owned Enterprises (VOEs) in Indonesia, as of 2021, has raised several pressing issues that warrant in-depth exploration and resolution. Among these issues, perhaps the most glaring is the challenge of inactive VOEs and those struggling to maintain their operational performance. Since the issuance of Law number 6 of 2014, the number of VOEs until 2021 has reached 57,266 (please refer Figure 1). The following diagram presents statistics on the development of VOE throughout Indonesia

Firstly, the staggering number of approximately 12,040 inactive VOEs across the nation is a matter of concern. These enterprises, established with the aim of benefiting rural communities and boosting local economies, currently lie dormant, failing to fulfill their intended roles. The reasons for this inactivity could range from insufficient resources and ineffective management to a lack of market access and technical know-how. This phenomenon underscores the need for comprehensive strategies that not only facilitate the establishment of VOEs but also sustain their activities over the long term.

Furthermore, the significant percentage of active VOEs, approximately 35%, grappling with performance difficulties is another pressing issue. These organizations, while technically operational, face a host of challenges that hinder their ability to thrive. These challenges may include financial instability, governance deficiencies, inadequate infrastructure, or market competitiveness. Addressing these issues is paramount, as the effectiveness of VOEs in promoting rural development and community welfare hinges on their sustained performance. The overarching concern of fraud within VOEs cannot be understated. Given the potential for mismanagement and corruption, the need for robust governance mechanisms becomes apparent. The absence of standardized governance indicators, as highlighted in the initial abstract, leaves VOEs susceptible to fraudulent activities. As a result, there is a pressing need to establish and enforce governance frameworks that not only ensure transparency and accountability but also deter fraudulent practices.

In addressing these multifaceted issues, it becomes clear that a holistic approach is required. This entails not only the development of governance indicators, as the initial abstract proposed, but also the provision of resources, capacity-building, and support mechanisms to bolster the capabilities of VOEs. Collaboration between government agencies, local communities, and relevant stakeholders is essential to formulate and implement effective strategies. Ultimately, the resolution of these issues is crucial in unlocking the full potential of VOEs as catalysts for rural development and prosperity in Indonesia.

Good Governance

The Development of Good Governance

Governance is a term that describes how an organization is run in terms of management, monitoring, and evaluation. Various definitions of governance have been presented by previous researchers. Rezaee (2008) defines good governance as the impact of the existence of a set of laws and regulations, market mechanisms, record standards, best practices, and the efforts of all organizers of an organization and stakeholders in the organization. The purpose of governance is to create checks and balances with the ultimate goal of creating and increasing long-lasting and sustainable shareholder value and protecting other stakeholders. Furthermore, the notion of governance is conveyed by Elahi (2009) who explains that governance is the exercise of economic, political, and administrative authority to manage the affairs of a country. The availability of good governance will provide normative guidance in organizational management (Pomeranz & Stedman, 2020).

There are different views regarding the principles of governance from various kinds of regulations around the world. van Doeveren (2011) concluded that there are five main principles of good governance, which consist of effectiveness and efficiency, accountability, transparency, participation, and the rule of law. Meanwhile, according to UNDP, which was concluded by Graham and Plumpetre (2003), the principles of good governance consist of legal supremacy, transparency, responsiveness, consensus orientation, equality and inclusivity, efficiency and effectiveness, and accountability. The difference in the conclusions above indicates that the principles of good governance are broad and very closely related to the form of organization whose governance will be assessed. Pomeranz and Stedman (2020) argue that in preparing the principles of good governance, attention must be paid to the needs of the community and what the ultimate goal of good governance indicators is. Of course, this will really depend on the form of performance evaluation, as expected later. A clear definition of good governance terms will greatly influence the evaluation of good governance performance (Pomeranz & Stedman, 2020).

In the context of social organizations, the principles of good governance will differ from those of business and government organizations. This is due to the duality of goals carried out by social organizations (Mswaka & Aluko, 2015). Not only that, the different goals for establishing social organizations in each country will result in different governance principles to be applied (Bertotti et al., 2014). Because of this, the literature on good governance in social organizations is limited. In the Indonesian context, governance principles have been regulated by the government in PP No. 11 of 2021. However, the principles contained in these regulations need to be derived in the form of governance indicators, which can later measure the implementation of governance in VOE.

The Framework of Good Governance at VOE

There are five VOE governance principles that have been conveyed in government regulation number 11 of 2021 which consist of professional, open and responsible, participatory, priority of local resources, and sustainability.

Professional

Professional means that VOE management must be carried out in accordance with existing rules and by actors who have sufficient ability and competence. The value of professionalism can be seen in the VOE management's compliance with applicable laws and regulations. In addition, professionalism is also reflected in the capabilities and competencies of VOE's human resources in carrying out activities at VOE. The value of professionalism will be reflected in the leadership skills possessed by the VOE director. When the VOE director has good leadership capabilities, VOE will have a clear direction for developing its business (Bass & Bass, 2009). When referring to the principles of good governance that already exist in the previous literature, this principle is related to the principle of "capability" presented by (Lockwood, 2010). In his research, Lockwood (2010) defines "capability" as the ability of an organization to manage resources, leadership, and knowledge in managing an organization. When an organization is able to manage resources, leadership, and knowledge, it can be said to be professional. This definition is also used as a reference by Pomeranz and Stedman (2020) in creating a good governance measurement for a program that runs in villages in America.

Open and responsible

Open means that the implementation of VOE governance can be monitored by the general public. All VOE management data and information can be easily accessed and displayed at any time. This form of openness reflects two-way communication between managers and interested stakeholders that can run well (Pomeranz & Stedman, 2020). Indicators of openness are not only accessible, but stakeholders who want to know information know where they can get the information they need. As well as being the most important thing in the aspect of openness, stakeholders are satisfied with the information they get from organizational managers (Lockwood, 2010; Pomeranz & Stedman, 2020). Indicators of openness are not only accessible, but stakeholders who want to know information know where they can get the information they need. As well as being the most important thing in the aspect of openness, stakeholders are satisfied with the information they get from organizational managers.

Being responsible means that VOE, as a business entity owned by the village, must be responsible for the village community. The form of VOE community accountability can be seen in VOE's ability to answer community questions regarding the utilization of village-owned assets used in VOE operations. Furthermore, VOE can convey the latest information regarding VOE management to the public. In addition, the community must also know who to contact when expressing concerns if a VOE operation endangers the community. This indicator is also used in the studies of Lockwood (2010), Pomeranz and Stedman (2020) in compiling indicators for measuring governance. Forms of accountability can be in the form of financial reports, activity reports, and business development reports carried out by VOE.

Participatory

Participatory means providing opportunities for community participation in the process of establishing and managing VOE, both in the form of participation and in the form of activities, by providing input of thoughts, energy, time, expertise, capital, or materials and taking part in utilizing and enjoying the results. When referring to the literature, the value of the participatory principle is reflected in the principle of inclusivity (Pomeranz & Stedman, 2020). They explained that the community was given the opportunity to convey their opinions to management in order to provide criticism and input. In addition, the number of public voices has a stake in determining the strategic decisions that will be taken by management. It can be interpreted that the meaning of participatory and inclusivity has the same meaning but with different terms and meanings. In the VOE context, participation can be reflected in the existence of capital that is included by the community, community involvement in considering new business units, and disclosure of information regarding the procurement of facilities and infrastructure to be carried out by VOE.

Prioritizing local resources

Prioritizing local resources means that in running a business, VOE must utilize natural resources and human resources from local villages. This principle is a form of privilege that only VOE can exercise. VOE is required to utilize human resources, who are indigenous people in the village, as workers. In addition, VOE is also required to use natural resources in the village as the main ingredient in its activities. Referring to previous research, the priority of human resources is included in the elements of capability (Pomeranz & Stedman, 2020) and legitimacy (Lockwood, 2010; Pomeranz & Stedman, 2020). In the VOE context, this principle can be reflected in the fact that all resources used in the VOE operational process must come from the village. In addition, VOE must also ensure that when opening a new business unit, local resources are the top priority that must be used.

Sustainability

Sustainability means that VOE development is expected to meet the needs of the village community in the present without compromising the ability of future generations of villages to meet their needs. Sustainability can be seen from two different perspectives. First, in terms of environmental sustainability. The entire process of VOE's business activities must consider the possibility of damage and pay attention to waste that is likely to cause problems in the future. The second aspect is seen from the perspective of organizational sustainability. The position of Director of VOE has certain limitations that have been regulated by government regulations. Therefore, every VOE must ensure that future VOE leadership is led by people who are competent and have a good understanding of VOE. To ensure that this happens, VOE must develop its human resources so that its sustainability continues. Referring to previous research, the principle of sustainability has the same meaning as "direction" in Pomeranz and Stedman (2020). They are of the opinion that the program being implemented must have an impact on their future generations. In addition, the impact of the program being implemented must be positive in the future (Pomeranz & Stedman, 2020). The use of different terms has the same goal of building indicators of good governance.

However, the preparation of more specific indicators to determine indicators of good governance in the VOE context requires further research. Currently, there is no standard good governance measurement indicator. This is the reason that, until now, there has been no formulation of a governance assessment that can be used as a measuring tool for VOE governance. Given the importance of measuring standardized governance, it is very important to set governance indicators based on governance principles in accordance with PP 11 of 2021. The goal is that the measurement of VOE governance has one standard and can be applied to all VOEs in Indonesia.

Prior Research on Good Governance at VOE

Governance research in the VOE context is still very limited. Widiastuti et al. (2019) through their research, designed governance indicators based on six principles: cooperative, participatory, emancipatory, transparent, accountable, and sustainable. The results of the study found that the indicators compiled were too broad to be applied to VOE, which was still in the pilot category. In addition, this research still needs to improve VOE governance indicators. Furthermore, one of the studies revealed that one of the factors that affected VOE performance was governance (Kurnianto & Iswanu, 2021). Unlike the research by Widiastuti et al. (2019), Kurnianto and Iswanu (2021) uses a quantitative approach using a questionnaire to prove the effect of good governance on VOE performance. Two studies that have been conducted use different research approaches but the same governance indicators. There has been not many research using governance principles in accordance with Government Regulation Number 11 of 2021.

During the journey of VOE development, which began in 2014, there were many cases that caused significant losses. There have been many cases of corruption, embezzlement of money by VOE management, and differences in vision and mission between the village head as a shareholder and the VOE Director as VOE management. As was the case in a village in Lampung Province, two people were arrested because they were proven guilty of embezzling VOE funds from 2019 to 2021 (Kompas, 2022). Another case was revealed in 2023 at one of the VOEs in the province of Bali. The VOE treasurer was proven to have committed criminal acts of corruption from 2014 to 2018 (CNN Indonesia, 2023). Furthermore, corruption cases were also carried out by village heads in West Java Province. The village head was proven to have embezzled 1.3 billion rupiah of VOE money (Kumparan, 2023). In addition to the examples of cases above, there are many other cases that have occurred in Indonesia. The occurrence of cases of fraud can be caused by the ineffectiveness of the governance system that has been properly implemented at VOE (Suryanto et al., 2020).

Governance is a crucial factor that must be possessed by social enterprises (Khalid et al., 2016; Low, 2006) including VOE. Governance is the structure that defines the relationship between principals, agents, and the company. The unavailability of measuring instruments that can guide the assessment of governance can lead to misinformation conveyed by management to stakeholders. In addition, good governance guidelines are useful for anticipating fraud in VOE management. As previously discussed, many cases have occurred due to poor VOE governance.

Refer to the applicable regulations. The importance of good governance has been listed in PP 11 of 2021 as follows:

"The establishment of BUMDesa is based on the business model, governance, form of organization, and type of business, as well as knowledge and technology"

Based on the regulations above, it is emphasized that VOE is required to carry out its activities with good governance so that its existence will have an economic and social impact on the village through the performance it produces. The implementation of good VOE governance will greatly determine the performance of VOE (Anggraeni, 2016; Hasibuan et al., 2022; Sari et al., 2022).

Conclusion

In conclusion, effective governance is of paramount importance within the realm of Village Owned Enterprises (VOEs) in Indonesia. These entities serve as vital drivers of rural economic development and community welfare, underscoring the need for meticulous management. Sound governance not only serves as a warning against fraudulent activities but also ensures alignment with the multifaceted expectations of stakeholders. Extensive research evidence reinforces the pivotal role of governance in shaping VOE performance, as exemplified in studies by Kurnianto and Iswanu (2021) and Sari et al. (2022). To comprehensively evaluate and enhance governance within VOEs, the establishment of standardized governance indicators is an urgent necessity.

In addition to government officials, the involvement of diverse stakeholders is equally vital. This includes representatives from the private sector, civil society organizations, and local communities who are directly impacted by governance practices. Academics with expertise in governance studies can provide the necessary academic rigor and analytical depth to the discussions. Furthermore, including relevant actors from within the Voice of the Environment (VOE) operations is indispensable. Their firsthand knowledge and experience in dealing with governance issues in the context of environmental initiatives can shed light on practical challenges and opportunities, ensuring that the developed indicators are not only comprehensive but also actionable.

This pursuit of governance indicators requires a rigorous conceptual study that accommodates the diverse array of resources, cultural intricacies, geographical disparities, and unique community dynamics found across Indonesia. Moreover, it must account for the distinct governance principles embedded in Government Regulation Number 11 of 2021. These indicators should serve not only as evaluative tools but also as catalysts for capacity-building and continuous improvement. By reinforcing the governance framework within VOEs, we not only protect their integrity but also empower them to optimally fulfill their pivotal role in advancing rural development and prosperity across Indonesia. The absence of specific indicators has resulted in inconsistent governance assessments across the nation.

Ultimately, the aim is to craft governance indicators that provide a holistic understanding of the realities of VOE operations in Indonesia. This inclusive approach ensures that these indicators are not only rooted in sound theoretical foundations but are also sensitive to the practical intricacies and diverse perspectives that shape governance in this dynamic and culturally rich nation. Future research endeavors must prioritize the development and implementation of tailored governance indicators suited to the nuanced needs of VOEs. Collaborative focus group discussions, engaging government officials, stakeholders, academics, and relevant actors, are indispensable in crafting the framework of governance indicators.

References

Ahmad Nadzri, F. A., Lokman, N., Syed Yusuf, S. N., & Naharuddin, S. (2021). Accountability and transparency of accredited social enterprises in Malaysia: website disclosure analysis. Management and Accounting Review (MAR), 20(3), 246-276. DOI:

Anggraeni, R. R. S. M. (2016). Peran Badan Usaha Milik Desa (BUMDES) Pada Kesejahteraan Masyarakat Pedesaan Studi Pada BUMDES Di Gunung Kidul, Yogyakarta [The Role of Village-Owned Enterprises (BUMDES) in the Welfare of Rural Communities Study on BUMDES in Gunung Kidul, Yogyakarta]. MODUS, 28(2), 155–167. DOI:

Bacq, S., & Eddleston, K. A. (2018). A Resource-Based View of Social Entrepreneurship: How Stewardship Culture Benefits Scale of Social Impact. Journal of Business Ethics, 152(3), 589–611. DOI:

Bass, B. M., & Bass, R. (2009). The Bass handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications. Simon and Schuster.

Bertotti, M., Han, Y., Netuveli, G., Sheridan, K., & Renton, A. (2014). Governance in South Korean social enterprises: Are there alternative models? Social Enterprise Journal, 10(1), 38-52. DOI:

British Council. (2021). The State of Social Enterprise in South East Asia.

CNN Indonesia. (2023, February 17). Diduga Korupsi, Bendahara BUMDes di Bali Terancam 20 Tahun Penjara [Suspected of Corruption, BUMDes Treasurer in Bali Threatens 20 Years in Prison]. https://www.cnnindonesia.com/nasional/20230216131846-12-913891/diduga-korupsi-bendahara-bumdes-di-bali-terancam-20-tahun-penjara.

Cornforth, C. (2012). Nonprofit Governance Research: Limitations of the Focus on Boards and Suggestions for New Directions. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(6), 1116–1135. DOI:

Dart, R. (2004). The legitimacy of social enterprise. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 14(4), 411-424. DOI:

Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2008). Social enterprise in Europe: recent trends and developments. Social Enterprise Journal, 4(3), 202–228. DOI:

Dey, P., & Teasdale, S. (2013). Social Enterprise and Dis/identification: The Politics of Identity Work in the English Third Sector. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 35(2), 248-270. DOI:

Elahi, K. Q. I. (2009). UNDP on good governance. International Journal of Social Economics, 36(12), 1167–1180. DOI:

Farmer, J., De Cotta, T., McKinnon, K., Barraket, J., Munoz, S.-A., Douglas, H., & Roy, M. J. (2016). Social enterprise and wellbeing in community life. Social Enterprise Journal, 12(2), 235–254. DOI:

Fuadi, R., Linda, Batara, G., & Sari, N. (2022). Analysis of village owned enterprises (BUMDes) financial performance before and during COVID-19 pandemic. E3S Web of Conferences, 340, 03004. DOI:

Graham, J. A., & Plumpetre, T. (2003). Principles for good governance in the 21st century (Policy brief no. 15). Institute on Governance.

Hasibuan, S. A., SIlalahi, P. R., & Tambunan, K. (2022). Peranan Badan Usaha Milik Desa (BUMDES) Pada Kesejahteraan Masyarakat Studi Kasus BUMDES di Desa Rasau Kecamatan Torgamba [The Role of Village-Owned Enterprises (BUMDES) in Community Welfare. Case Study of BUMDES in Rasau Village, Torgamba District. South Labuhan Batu Regency]. South Labuhan Batu Regency.

Johari, R. J., Sanusi, Z. M., & Shafei, N. A. (2020). Social Enterprises’ Performance: The Influences of Corporate Structure, Corporate Monitoring Process and Corporate Controlling Process. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 10(13). DOI:

Khalid, M. A., Alam, M. M., & Said, J. (2016). Empirical Assessment of Good Governance in the Public Sector of Malaysia. Economics & Sociology, 9(4), 289-304. DOI:

Khan, S. H., Yasir, M., Shah, H. A., & Majid, A. (2021). Role of Social Capital and Social Value Creation in Augmenting Sustainable Performance of Social Enterprises: Moderating Role of Social Innovation. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences, 15(1), 117-137.

Kompas. (2022, October 5). Korupsi Dana BUMDes Rp 1,2 Miliar, Bapak dan Anak di Lampung Ditahan [Corruption in BUMDes Funds Rp. 1.2 Billion, Father and Son in Lampung Detained]. https://regional.kompas.com/read/2022/10/05/131905978/korupsi-dana-bumdes-rp-12-miliar-bapak-dan-anak-di-lampung-ditahan?page=all

Kumparan. (2023, May 8). Kades di Cianjur Ditangkap, Diduga Korupsi Dana BUMDes Rp 1,3 Miliar [Village Head in Cianjur Arrested, Suspected of Corruption in BUMDes Funds of IDR 1.3 Billion]. https://kumparan.com/kumparannews/kades-di-cianjur-ditangkap-diduga-korupsi-dana-bumdes-rp-1-3-miliar-20MYFpQRoeS

Kurnianto, S., & Iswanu, B. (2021). Governance and performance of village-owned enterprises (BUMDES). Jurnal Riset Akuntansi dan Bisnis Airlangga, 6(2), 1150-1170. Online. www.jraba.org. DOI: 10.20473/jraba.v6i2.187

Larner, J., & Mason, C. (2014). Beyond box-ticking: A study of stakeholder involvement in social enterprise governance. Corporate Governance (Bingley), 14(2), 181–196. DOI:

Lockwood, M. (2010). Good governance for terrestrial protected areas: A framework, principles and performance outcomes. Journal of Environmental Management, 91(3), 754–766. DOI:

Low, C. (2006). A framework for the governance of social enterprise. International Journal of Social Economics, 33(5–6), 376–385. DOI:

Mswaka, W., & Aluko, O. (2015). Corporate governance practices and outcomes in social enterprises in the UK: A case study of South Yorkshire. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 28(1), 57-71. DOI:

Poledrini, S., & Tortia, E. C. (2020). Social Enterprises: Evolution of the Organizational Model and Application to the Italian Case. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 10(4). DOI:

Pomeranz, E. F., & Stedman, R. C. (2020). Measuring good governance: piloting an instrument for evaluating good governance principles. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(3), 428-440. DOI:

Powell, M., Gillett, A., & Doherty, B. (2019). Sustainability in social enterprise: hybrid organizing in public services. Public Management Review, 21(2), 159–186. DOI:

Rezaee, Z. (2008). Corporate Governance and Ethics (1st ed., Vol. 1). John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Sari, R. N., Junita, D., Anugerah, R., & Nanda, S. T. (2021). Social entrepreneurship, transformational leadership and organizational performance: The mediating role of organizational learning. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 23(2), 464-480. DOI:

Sari, R. N., Junita, D., Anugerah, R., Nanda, S. T., & Zenita, R. (2022). Effect of governance practices on value co-creation and organizational performance: Evidence from village-owned enterprises in Riau, Indonesia. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 20(4), 532–543. DOI:

Seelos, C., & Mair, J. (2005). Social entrepreneurship: Creating new business models to serve the poor. Business Horizons, 48(3), 241–246. DOI:

Sengupta, S., & Sahay, A. (2017). Social entrepreneurship research in Asia-Pacific: perspectives and opportunities. Social Enterprise Journal, 13(1), 17–37. DOI:

Singh, K., & Rastogi, S. (2023). Corporate governance and financial performance: evidence from listed SMEs in India. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 30(4), 1400-1423. DOI:

Spear, R., Cornforth, C., & Aiken, M. (2007). For love and money: Governance and social enterprise.

Suryanto, R., Mohammed, N., & Yaya, R. (2020). Fraud Frevention for Sustainable Social Enterprise Using Participative Social Governance. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the First International Conference on Financial Forensics and Fraud, ICFF, 13-14 August 2019, Bali, Indonesia. DOI:

Tausl Prochazkova, P., & Noskova, M. (2020). An application of input-output analysis to social enterprises: a case of the Czech Republic. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 12(4), 495–522. DOI:

United Nations. (2020). World Youth Report 2020. World Youth Report. DOI:

van Doeveren, V. (2011). Rethinking Good Governance: Identifying Common Principles. Public Integrity, 13(4), 301–318. DOI:

van Twuijver, M. W., Olmedo, L., O'Shaughnessy, M., & Hennessy, T. (2020). Rural social enterprises in Europe: A systematic literature review. Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, 35(2), 121-142. DOI:

Waddock, S. A., & Post, J. E. (1991). Social Entrepreneurs and Catalytic Change. Public Administration Review, 51(5), 393. DOI:

Widiastuti, H., Putra, W. M., Utami, E. R., & Suryanto, R. (2019). Menakar tata kelola badan usaha milik desa di Indonesia [Assessing the governance of village-owned enterprises in Indonesia]. Jurnal Ekonomi dan Bisnis, 22(2), 257-288. DOI:

Yunus, M., Moingeon, B., & Lehmann-Ortega, L. (2010). Building social business models: Lessons from the grameen experience. Long Range Planning, 43(2–3), 308–325. DOI:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

15 November 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-130-0

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

131

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1281

Subjects

Technology advancement, humanities, management, sustainability, business

Cite this article as:

Nanda, S. T., Johari, R. J., Sanusi, Z. M., Sari, R. N., Anugerah, R., & Hitam, M. (2023). Cultivating Sustainable Performance: A Framework for Governance Indicators in Village Owned Enterprises. In J. Said, D. Daud, N. Erum, N. B. Zakaria, S. Zolkaflil, & N. Yahya (Eds.), Building a Sustainable Future: Fostering Synergy Between Technology, Business and Humanity, vol 131. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 643-654). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2023.11.55