Abstract

Islamic banks face various business risks similar to regular banks, such as credit, investment, operational, and market risks. However, the unique risk of not complying with Shariah principles is particularly crucial due to the belief that operations are carried out in accordance with Shariah. The internal Shariah auditor, acting as the third line of defense, plays a vital role in ensuring effective management of Shariah Non-Compliance Risk (SNCR) and proper implementation of internal controls for Shariah compliance. Key stakeholders like the Shariah board, audit board, and external auditors often depend on the work of the internal Shariah auditor. Hence, these auditors must possess strong judgment skills, especially concerning SNCR, to maintain accuracy and trustworthiness in all reporting levels. Consequently, this study aims to offer a theoretical insight into the factors influencing internal Shariah auditors' judgment in SNCR by reviewing literature on both traditional and Shariah audits. To understand the aspects impacting internal Shariah auditors' judgment, the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) is employed, examining attributes affecting their performance in SNCR judgment. The research suggests that the internal Shariah auditor's personal capabilities (competency) and external factors (efficient Shariah risk management) contribute to their ability to make skilled and impartial judgments in SNCR.

Keywords: Islamic Banks, Internal Shariah Auditor, Judgment, Shariah Non-Compliance Risk

Introduction

Due to the rapid growth of the Islamic financial system since its inception during the past few decades, the range of services provided by Islamic Financial Institutions (hereinafter "IFIs") has broadened. This expansion was prompted by Muslims' growing interest in non-Western economic models. Since riba (interest) is forbidden in Islam, Muslims have formed IFIs all around the world to ensure that it is not practised in their economy. According to the Global report on Islamic Finance 2020, the industry's yearly growth rate in 2018 was the best it had been since the 2008 global financial crisis, with worldwide Islamic finance assets increasing by 14% to reach US$2.88 trillion. The majority of the $1.99 trillion total worth of Islamic Finance is held by the Islamic banking sector. 69% of all assets in Islamic finance are held by the world's 526 Islamic banks (including their branches and representative offices) (Mohamed et al., 2020). Corporate governance in IFI must be strong and efficient to meet the growing demand for Islamic banking products and services while maintaining compliance with Shariah law. IFIs have sprung up all over the world as a result of Muslims' desire to implement Islamic law prohibiting usury (riba) in their respective economies.

Similar to their conventional counterparts, Islamic banks incur risks from equity investment, market risk, credit risk, operational risk, etc. A failure to adhere to Shariah is considered as posing a unique and particularly severe risk (Mohd Noor et al., 2018; Mohamad Puad et al., 2020; Rosman et al., 2017). Some international financial institutions (IFIs) have provided services and products that don't adhere to Shariah principles and norms set forth by authorities due to weak governance (Khatib et al., 2022). Therefore, any breach of Shariah would undoubtedly damage stakeholders' commitment to Islamic banking, and might result in money being withheld, income being lost, and most crucially, reputational injury and image deterioration (Azrak et al., 2016). Customers' trust in Islamic financial services as a whole would be seriously damaged if they learned that some of the products in their portfolio did not adhere to Shariah (Abdul Rahman, 2010). An internal Shariah audit is crucial to achieving maqasid al-Shariah (Islamic law's goals) (Yaacob & Donglah, 2012), lowering SNCR (Shariah Non-Compliance Risks) (Sani & Abubakar, 2021) and gaining stakeholders' trust in order to seek Allah's pleasure (Ridhwanullah).

An impartial third party called the Shariah auditor assesses and certifies whether or not an Islamic bank complies with Shariah principles and laws. The view expressed by Shariah auditors in their reports is crucial for the end user. Multistakeholder organisations usually rely on the findings of an internal Shariah auditor, as Sani and Abubakar (2021) point out. The Shariah Board will deliver its opinion on the annual financial statements based on the report supplied by the internal Shariah auditor. The Shariah Board also confers with the external auditor before the latter gives their opinion on the financial statements. Internal Shariah auditing was thus relied upon implicitly (Sani & Abubakar, 2021). Given the extensive chain of dependencies on their work to guarantee the achievement of organisational goals outlined in Islamic banking, internal Shariah auditors must be efficient in carrying out their tasks. This can only be done if the internal shariah auditor is certain that the controls and transactions they evaluated adhere to the tenets of Islamic law, as outlined in the shariah. At the end of the procedure, they'll be able to see if the IFI's internal controls are adequate and efficient.

Shariah audits operate as the eyes and ears of Shariah boards, therefore their thoroughness and accuracy affect the institution's commitment to Shariah compliance (Rashid & Ghazi, 2021). Considering the severe consequences of violating Shariah in Islamic banking, the internal Shariah auditor must exercise the highest quality judgment, particularly audit judgment in SNCR. Razali (2020) found that risk judgement is the most critical judgment in order to ensure the success of any given internal audit engagement. Good judgement in risk assessment during the planning may aid in using good judgement during the judgment phase that follows. However, poor judgment in SNCR may result in designing weak analytical procedures, which may contribute to the opposite result (i.e., wrong sample selection, inappropriate testing, and improper internal Shariah audit conclusion). Due to the importance of risk assessment in ensuring Shariah audit quality and mitigating adverse consequences of SNCR to Islamic banking, a study on factors affecting internal Shariah auditor’s ability to effectively perform their work, particularly in SNCR judgment performance is crucial.

The belief that there is only one God, Allah S.W.T., is called tauhid and is central to Islamic doctrine. Shariah-compliant economies recognize Allah S.W.T. as the true owner of all property (Hanefah et al., 2020). Muslims, in their role as guardian (khalifah), are expected to ensure that the world's wealth is distributed fairly and justly (Hanefah et al., 2020). As a result, the Shariah auditor's judgement would be influenced by the Islamic worldview, which has quite different pillars than Western philosophy. The factors influencing the internal Shariah auditor's decision must be studied because the Islamic perspective on SNCR is unique from all others.

Shariah audit, its effectiveness, drivers, and outcomes have received less attention in the literature than corporate governance in IFIs (Alahmadi et al., 2017; Khatib et al., 2022; Lahsasna, 2016; Yasoa' et al., 2020). In light of this, the principles and elements that impact Shariah auditors when they exercise judgement are mostly unknown, and knowledge of shariah auditing as a whole is limited at best (Yahya & Mahzan, 2012). According to the reviewed literature, the performance of an internal Shariah auditor's judgement has not been studied extensively, especially in SNCR. According to Rashid and Ghazi (2021), there is a need to draw conclusions from the extensive body of research literature on the quality of conventional audits in order to ensure the quality of Shariah audit in Islamic banking. This study tries to fill this knowledge gap by providing a new angle on the existing literature on Shariah auditing. Given the significance of risk judgement in Shariah auditing, the purpose of this research is to suggest the factors that influence the judgement performance of internal Shariah auditors with regard to SNCR.

Bonner (1999) defined judging as the mental process of "forming an idea, opinion, or estimate about an object, an event, a state, or another type of phenomenon. “Whether a person is able to predict the future or assess the current situation depends on the state of their mind. After an evaluation is made, the student will participate in a decision-making activity that requires them to pick one of several possible outcomes” (p. 385). Researchers in JDM typically use a cognitive framework to deduce how auditors weigh evidence and reach conclusions (Trotman et al., 2011). Therefore, numerous components of Social Cognition Theory (SCT) (Bandura, 1986) were used to conceptualise the appropriate theoretical framework for the present investigation.

Literature Review and Propositions Development

Shariah audit in IFIs

The necessity for a Shariah audit arises due to the obligation for Islamic banking to adhere to Shariah principles. The growing demand of Islamic banking and the consequences of non-compliance with Shariah requires IFIs to have a "check and balance" mechanism in the form of Shariah audit (Yasoa' et al., 2020). According to Yaacob and Donglah (2012) this mechanism is compatible with the objectives of its establishment, the 'Maqasid as-Shariah. Khan (1985) did some ground-breaking research to show how auditing works differently in the setting of Islamic economics. The auditor's only responsibility in a standard audit is to the company's owners. He doesn't give a hoot about the integrity of the management's decisions or the auditor's moral compass. According to early Islamic cultural practises and doctrines (Khan, 1985), the auditor is responsible to financiers, evaluates management practises, and reports on their conformance with Shariah (such as contract fulfilment, honesty, avoiding monopolies, and excess).

Comparable to the conventional auditing process is the sharia auditing process. However, Shariah law must also be followed. The Islamic worldview clearly distinguished between Islamic and Western economic practises. Interest (Riba'), uncertainty (Gharar), and gambling (Masir) are all examples of activities that are forbidden by Shariah. Alcohol, pig, and other delicacies that are forbidden by Islam cannot be consumed or invested in. To ensure that Islamic institutions are managed in accordance with Islamic principles, Shariah auditing (also known as Islamic religious auditing) provides direction and monitors performance.

The Accounting and Auditing Organisations for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) has created and released rules in an effort to improve Islamic finance globally. In order to advance Islamic banking, the institute provides training in Shariah auditing techniques. The definition of a Shariah audit given by AAOIFI is ambiguous. In contrast, according to paragraph 2 of the AAOIFI's Governance Standards for IFIs No.2 (GSIFI 2), Shariah Review is "an examination of the extent to which an IFI is compliant, in all activities, with the Shariah. As part of this procedure, documents including memoranda of association and articles of incorporation, financial accounts, audit reports (especially those from the central bank), circulars, etc., will be examined. This is the most exact description of a Shariah audit in the literature (Khalid et al., 2018). Shariah audit is described as "a function that provides an independent assessment of the IFI's internal control, risk management systems, and governance processes, as well as the overall compliance of the IFI's operations, business, affairs, and activities with Shariah" (Bank Negara Malaysia, 2019) by the regulators in Malaysia's most recent Shariah governance framework.

An academic definition of a Shariah audit in Islamic financial services is provided by Abdul Rahman (2010) as "the accumulation and evaluation of evidence to determine and report on the degree of correspondence between the information and established criteria for Shariah compliance purposes". The term "shariah auditing" is defined by Khatib et al. (2022) as "the process of financial institutions that follow Islamic Shariah to the extent of their compliance with all activities, including contracts, risks, and financial statement operations". The process entails evaluating how well Islamic financial organisations follow Islamic principles and regulations when conducting Islamic financial transactions. Shariah auditing, according to the aforementioned definitions, is the process by which all the operations performed by Islamic banking are examined and evaluated, including contracts, agreements, policies, products, and transactions. In order to provide independent assurance that an Islamic enterprise is running in accordance with Shariah, an auditor must conduct an audit.

The auditing processes used in Islamic banks are not yet standardized. The rules for Islamic banking are different in every country. While some countries have adopted the criteria put forth by the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOFI) in its entirety, others have done so only partially (Khalid et al., 2017). Additionally, other than following the Shariah governance framework issued by the regulator such as IFIs in Malaysia, the auditor will also refer to the traditional audit standards published by The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA), such as the International Standards Professional Practice of Shariah Governance Framework (IPPF) (Mohd Ali & Kasim, 2019) and International Standards Professional Practice of Internal Auditing (ISPPIA) (Puad et al., 2020b; Yahya & Mahzan, 2012).

Shariah non-compliance risk

The Institute of Internal Auditors (2016) define risk as the "probability that an event will occur that will have an impact on the achievement of objectives." Investment risk is a complex topic that incorporates the possibility of investment losses (Alam, 2019). The Committee of Sponsoring Organisations of the Treadway Commission's ERM Framework also defines risk in relation to commercial enterprise management as "the possibility that an event will occur and adversely affect the achievement of an objective" (COSO, 2004). Given the description provided above, it is possible to define risk as the possibility that something will occur that will make it more difficult for the organisation to achieve its objectives.

Risk is frequently referred to as mukhatarah, which comes from the Arabic word khatar as its origin. Khatar is described as "fear of destruction" in Al-Razi's Mukhtar al-Sihah, an edited version of Al-Sihah by Al-Jawhari (Hassan, 2016). Elgari (2003) presented the first comprehensive examination of hazards in Islamic finance (Mohd Noor et al., 2018). As he said, "the situation that involves the probability of deviation from the path that leads to the expected or usual result" and "the likelihood of loss" is what he meant by the idea of mukhatarah (risk).

The risks that IFIs face are similar to the ones faced by conventional financial institutions. For instance, credit, market, liquidity, and operational risks. However, because adhering to Shariah's regulations and values is necessary, IFIs face SNCR, that is, unique and specific risks that arise from the contractual design that ought to comply with Shariah (Mohd Noor et al., 2018). In Islamic finance, the terminology of SNCR was introduced by the Islamic Financial Service Board in 2005 as “the risk that arises from Institutions (other than Insurance Institutions) offering only Islamic Financial Services (IIFS) failure to comply with the Shariah rules and principles determined by the Shariah Board of the IIFS or the relevant body in the jurisdiction in which the IIFS operate (Islamic Financial Service Board, 2005).

According to Sani and Abubakar (2021), SNCR refers to the dangers posed to IFIs by transgressing Shariah laws and norms. According to the authors, SNCR should be the outcome of failure to abide by the counterparties' shariah rules and principles as well as mainstream industry shariah viewpoints, such as those of the internationally renowned shariah organisations AAOIFI and the International Islamic Fiqh Academy of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation. The authors argue that SNCR should not be restricted to disregarding the Shariah laws and regulations set forth by the SB of IFI or other applicable authority. Since Shariah is the core identity, IFIs should strive to always comply with it while maintaining a risk appetite for SNCR that is almost zero. A firm can hardly operate without taking on inherent risks, therefore having a 0% appetite for SNCR would be illogical and unworkable (Sani & Abubakar, 2021).

Failing to comply with Shariah means that IFIs deserve specific attention because it may erode customers’ confidence and the whole financial system. According to Omar and Hassan (2019) SNCR may originate from the product's structure. Any violation of Shariah rules for the contract features may lead to SNC. For instance, in Murabahah financing (also referred to as cost-plus financing), the seller must explicitly inform the purchaser about the cost and the amount of profit the seller will charge in addition to the cost incurred. Attention must be given to the contract features, or otherwise, the Murabahah transaction becomes invalid, according to Shariah. The documentation must not violate Shariah principles, as Islamic financing differs from conventional, with different requirements in the product and service terms and conditions.

Improper product execution can also result in Shariah Non-Compliance (SNC) even if the underlying contract follows Shariah's rules and principles. For instance, according to the study, Ali and Hassan (2020) found that the improper sequencing of the sale contract—by which the asset is sold to the client before the bank buys it from a broker—is the most frequent SNC occurrence in tawarruq financing. Weak technology would pose a serious danger to SNCR in the interim. For instance, in IT banking, a system flaw leads in the letter offer's information containing a ta'widh value that was incorrectly calculated (Ayedh et al., 2021). In addition, improper marketing and advertising may present a deceptive picture of the Islamic bank and the product offered, which might harm the public's opinion of IFIs (Omar & Hassan, 2019). In other words, SNCR may occur but is not limited to products, operational processes, the people involved, documentation and contracts, policies and procedures, the technology supporting the operations, and such actions that call for respect to shariah laws (Sultan, 2007). This indicates that SNCR is part of operational risk to IFIs.

The risk associated with failing to adhere to Shariah principles is considered as unique and substantial in IFIs, despite the fact that the distinctive contractual features have exposed IFIs to a variety of risks (Mohd Noor et al., 2018; Mohamad Puad et al., 2020; Rosman et al., 2017). Losses resulting from SNCR may be both monetary and non-monetary (Sani & Abubakar, 2021). Furthermore, failure to comply with Shariah causes various legal and reputational issues for the guilty institutions in this world, and the guilty person also has divine accountability in the afterlife (Najeeb & Ibrahim, 2014).

Shariah auditor’s judgment

An auditor's work in auditing is frequently evaluated based on their judgment performance (Iskandar & Sanusi, 2011). Asare et al. (2013) asserted that the auditing process is a series of steps that require internal auditors to exercise their professional judgment. Every audit phase starting from the planning and followed by scoping, testing, evaluation, and reporting, involve audit judgment and decisions. The judgments and decisions made during each phase affect subsequent phases. For instance, inadequate risk assessments will affect scoping decisions. Therefore, the performance of later-stage judgments is largely dependent on judgments made in earlier stages (Razali, 2020). Hence, it could be said that the audit result depends on the audit judgment.

From the academic perspective, Bonner (1999) defined judgment as the mental activity of "forming an idea, opinion, or estimate about an object, an event, a state, or another type of phenomenon". The person's mental activity affect whether they foresee the future or evaluate the existing situation. Decision-making exercises that include selecting from a range of options will come after forming a judgment (p. 385). Wedemeyer (2010), from a professional perspective, defined judgment any decision or evaluation made by an auditor that impacts or regulates the process and outcome of an audit (pp. 320–321).

Accounting and auditing have become more aware of how important JDM is in their fields because people like managers, auditors, financial analysts, accountants, and standard setters make important decisions and judgments (Mala & Chand, 2015). In addition to coworkers, business owners, and the institution or organisation itself, an individual's judgement can have an impact on their professional reputation and performance. Thus, people who rely on the JDM made by others may suffer financial loss as a result of someone else's poor judgment. Consequently, result in undesirable legal consequences, such as civil litigation settlements.

Sulaiman et al. (2018) conducted a review analysis on 84 empirical studies and publications from the year 1980 to the year 2016. The study found that the majority of studies on auditors' JDM in performing audit operations, including risk assessments, the appraisal of analytical techniques and supporting data, the auditor's determination of what has to be corrected, and going concern judgement. A number of factors, including ability, decision aids, multi-person judgement, heuristics and biases, knowledge and memory, probabilistic judgement, environment and motivation, and policy capturing, have been proven to have a substantial impact on the auditor's judgement performance.

The four main goals of JDM auditing research, according to Trotman (1998), are to (i) assess the quality of auditor judgements, (ii) describe how auditors make judgements and what influences judgement performance, (iii) test theories of the cognitive processes that produce the judgement, and (iv) develop and test remedies for any shortcomings discovered above. As a subset of the larger field of psychological study known as behavioural decision theory, judgement and decision-making (JDM) research in auditing examines individual and small-group judgements and decision-making in order to better understand how judgements or decisions are made and how they might be improved. To assure the quality of the Shariah audit, studies on the elements that improve the judgement of Shariah auditors in Islamic banking should be conducted (Rashid & Ghazi, 2021). This is because multistakeholder relies on the internal Shariah auditor's work, and if the SNCR judgement of the internal Shariah auditor is flawed, the multistakeholder's judgement will also be flawed (i.e., Shariah board, audit committee, external auditor). Consequently, it may cause significant losses to the Islamic banking.

The Arabic word ra'y is the source of the term judgment in Islam. The definition of Ra'y in the Hans Wehr dictionary of contemporary written Arabic is "opinion, idea, view, notion, and concept." In addition, the dictionary defined ra'y in Islamic law as an individual's judgment-based subjective opinion and choice (Wehr, 1976). The simplest and most basic kind of reasoning is ra'y, and it was crucial in the early days of Islamic jurisprudence. Sound personal judgment and opinion are referred to as ra'y (Shafiq, 1984). Due to the primary goal of Shariah auditing, which is to protect Shariah principles, internal Shariah auditors in Islamic banking may reach different conclusions than traditional internal auditors. The objective is not only to protect the business stakeholders but also for the maslahah of the ummah (public interest) (Yasoa' et al., 2020), so in addition to adhering to professional auditing ethics, the internal Shariah auditor should also adhere to Islamic ethics such as vicegerency. Internal Shariah auditors should therefore consistently maintain Shariah principles in all of their judgments, decisions, and actions.

Owing to different perspectives that is to uphold Shariah as compared to conventional wisdom, this undoubtedly will affect how the internal Shariah auditors effectively process information to make judgments. Studies on the variables influencing the internal Shariah auditor's judgement are thus necessary, especially in the case of SNCR, which is particular to the Islamic viewpoint. To preserve justice and fairness in society and support Islamic banking in achieving its aims of adhering to Shariah norms and principles, the internal Shariah auditor must exercise good judgement. Internal Shariah auditors should therefore consistently uphold Shariah principles in all of their judgements, decisions, and actions.

Competency and SNCR judgment

Audit success relies on the quality of human resources, such as competent and reliable professional expertise to strategize the work plan and review the result. Competency is the ability of the individual successfully perform a specific task (Mohd Ali et al., 2020). The concept can be applied to any group or individual that has found sustained success. Internal auditors, according to Asmara (2017) need to have enough knowledge, expertise, and experience to exercise good judgement when performing auditing duties. This supports Libby and Luft (1993) earlier research, which found that one of the key factors affecting accounting performance is competence. With the right background information, an auditor may comprehend the assignment and successfully finish it. The authors went on to argue that the auditor benefits from the experience they get on the job not just because their knowledge base grows, but also because they learn to better categorise and use the information they gather.

The lack of a competency framework for Shariah auditors in IFIs is one of the difficulties brought up by the previous research. An understanding of auditing and accounting principles is essential for a Shariah auditor, according to the literature (Kasim & Sanusi, 2013). To do their jobs well, Shariah auditors need training in auditing in addition to certification in Shariah knowledge, particularly in Fiqh Muamalat (Khalid et al., 2017). To guarantee that Shariah is being administered appropriately and that all IFI actions are in accordance with Shariah principles, this is done. All participants in Yahya and Mahzan (2012) study believed that familiarity with Shariah was essential for internal auditors, especially those who planned to take part in audits based on Shariah principles. If internal auditors are to detect violations of these principles in Islamic operations and transactions, they must be able to identify and understand the current situation of each Shariah principle.

In 2020, Mohd Ali et al. presented a knowledge-skills-attributes (KSOC) competency model for Shariah auditors. For the purposes of delivering quality assurance services and contributing to the Islamic banking business, "knowledge" refers to familiarity with internal control and auditing procedures. In addition, Shariah auditors need expertise in Fiqh Muamalat and Usul Fiqh, as well as knowledge of Islamic banking's culture, sector, and any changes in Shariah governance that could affect the industry's ability to function, in order to carry out the audit effectively. Technical auditing skills in IFIs pertain to the Shariah auditor's ability to spot any potential SNCR, as well as other talents such report writing, analytical thinking, communicating, and negotiation. Shariah auditors working for reputable financial institutions must be proficient in auditing retail or consumer goods, corporate, investments, Islamic capital markets, and treasury. The remaining qualities and behavioural skills have to do with things like optimism, cooperation, teamwork, management, and leadership. The Shariah auditor should now have the expertise (Mohd Ali et al., 2020) to handle audit-related challenges competently and deliver audit findings with assurance.

Rashid and Ghazi (2021) assert that the level of expertise of the auditor has a significant impact on the Shariah audit's quality. Assessing and identifying Shariah risk in a wide range of financial arrangements, contracts, and transactions calls for specialized knowledge on the side of the auditor. This capability requires not just the standard assurance skills and techniques, but also familiarity with Shariah law. A Shariah auditor cannot assess the sufficiency, efficacy, and efficiency of the Shariah controls in the IFI without being aware of how SNCR works. As a result, if the inherent risk or control risk is not thoroughly understood at the planning stage, subpar analytical procedures will be created. Similarly, the quality of the Shariah audit may suffer if any major misrepresentation goes undetected, increasing the engagement risk. Khalid and Sarea (2019) agree, having discovered that the reason internal Shariah auditors don't catch SNC is because to incompetence. This is because of the difficulties the sector experiences as a result of a shortage of skill in Shariah audits. In order to guarantee a strong internal control that complies with Shariah and to assist in the management of SNCR, it has been demonstrated via prior research that the competence of internal Shariah auditors is essential.

The auditor's lack of knowledge, experience, and talents might lead to flaws in his reasoning, which can then impact his judgement (Deliu, 2020). Internal Shariah auditing is less successful due to a shortage of competent manpower, according to research by Khalid and Sarea (2019). The integrity of shariah audits at IFIs is in jeopardy due to a shortage of skilled Shariah auditors in the market (Isa et al., 2020; Kasim et al., 2009; Khalid et al., 2017; Mohd Ali & Kasim, 2019; Puad et al., 2020a). SNCR may occur because the auditor has trouble spotting shariah risk or operational risk issues (Puad et al., 2020a). Therefore, it is essential to provide the internal Shariah auditors with the appropriate training programmes and workshops to increase their competence and strengthen their performance (Algabry et al., 2020; Islam & Bhuiyan, 2021) particularly in SNCR judgement.

Prior research found that a highly competent internal auditor leads to superior audit judgement. Razali (2020) found experience has a beneficial impact on risk judgement performance as a proxy for competency among internal auditors. Asmara (2017) conducted a similar investigation and came to a similar conclusion on the impact of internal auditor competency on auditors' professional judgement. Thus, the following propositions are formulated:

P1: Internal Shariah auditor's competency affects their SNCR judgment performance positively.

Effective Shariah risk management and SNCR judgment

While performing JDM duties, an individual's immediate environment has an impact on the quality of their JDM (Bonner, 2008). Miledi (2022) opined judging as a social practice or "collective endeavor." The person does not impose judgment on others directly. Through conversational (interaction, communication, and discourse) and institutional procedures (review process and independent review), judgment is built, learnt, readjusted, and reconstructed. The use of consultation during an audit gives the auditors new, pertinent knowledge that can help them use professional judgment. Therefore, when they are unsure or unclear about the audit assignment, auditors seek informal help from an expert inside or outside their organization (Miledi, 2022).

Prior study has highlighted the importance of internal auditors being informed and aware of the firm's risk to excel in their risk judgment, particularly in audit planning. The chief internal auditor needs to be aware of the business risks the organization faces (Selim & McNamee, 1999). As a result, the chief internal auditor must take part in the discussion on organizational risk, particularly in the department responsible for strategic planning. The strategic planning team defines the company's business goals, lists its most important resources, initiatives, and procedures, and identifies business risks and opportunities. This knowledge is necessary for the chief internal auditor to participate actively in audit planning (Selim & McNamee, 1999). Dickinson (2010) argued that internal auditors and risk management must leverage each other and constantly expand their knowledge and understanding of the environment in which they operate. They must work within the same risk management framework and engage in communication to constantly question each other's perspectives of the nature and severity of the risk profile (Dickinson, 2010).

The above study explains how consultations or advice from others help the internal Shariah auditor to broaden his understanding of the situation and consequently improve his judgment. This was also supported by Professor Doctor Zurina Shafii, Professor from Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia (USIM) in her speech on the Shariah auditing structure and process webinar held on 3rd March 2022. According to her, risk identification is important because if the auditor fails to identify the critical risk inherent to the product, an ineffective audit plan will be produced. As a consequence, it will affect the audit program developed because the audit objectives did not address the risk area in the scope of the audit. She emphasises the significance of Shariah auditors having a good working relationship with the Shariah risk management at IFI in order to give impacting items to the stakeholders. The purpose is to provide input to the Shariah auditor on which areas are important for the internal Shariah auditor to cover and focus on (Centre for Research and Training, 2022).

In the same webinar, Mr. Ahmad Zainal Abidin, the Shariah audit manager of Minhaj Shariah Financial Advisory, Dubai, explained that an internal Shariah auditor could not work in silo. They also need to rely on Shariah risk management and Shariah reviewers. For example, to do a risk-based audit, the internal Shariah auditor needs to refer to the risk profiling provided by the risk management. The internal Shariah auditor needs to check whether all risk has been identified (existing and emerging risk) by risk management. The internal Shariah auditor then takes the risk profiling prepared by the risk management for their reference. On top of that, risk management should already be well established because they comprehensively do the process of risk assessment and identification. It will be difficult for the internal Shariah auditor to justify if they set the level of risk as high, medium, or low because they did not undertake the overall process as the risk management does. As a result, a working relationship with risk management is essential for internal Shariah auditors to effectively conduct risk-based audits (Centre for Research and Training, 2022).

According to SGF 2010 paragraph 7.1, the Shariah audit function closely works with the Shariah risk management function in ensuring that Islamic financial activities are not exposed to SNCR (Bank Negara Malaysia, 2010). All potential SNCR should be identified through shariah risk management, along with any necessary corrective actions to lower risk. The internal Shariah audit function implements the risk-based audit process after the Shariah risk management function in order to provide objective assurance regarding the level of Shariah compliance and to reduce risk in the business operation of IFIs (Hanefah et al., 2020). In order to ensure Shariah compliance in their Islamic financial activities and operations, Islamic banks may be able to achieve their goal with the aid of a strong, independent relationship between their internal Shariah auditor and Shariah risk management. They both have unbreakable biological connection (Ahmad & Lateh, 2020).

Previous studies stated that, in order to properly perform their duties and maintain their independence, Shariah auditors need to interact closely with other Shariah experts in IFIs (Puad et al., 2020a; Yazkhiruni et al., 2018; Yasoa' et al., 2020). This is due to challenges face by the auditors in identifying Shariah risk due to lack of qualification or experience in Shariah audit. Therefore, providing advice on Shariah matters by the Shariah expertise in Islamic banks can aid the internal Shariah auditors to effectively perform assessments on SNCR during audit planning. Hence, effective Shariah risk management would contribute to high performance in SNCR judgment of internal Shariah auditors due to relying on effective Shariah risk information provided to them. Thus, the following propositions are formulated:

P2: Effective Shariah risk management affects internal Shariah auditor's SNCR judgment performance positively.

Proposed Theoretical Framework and the Underpinning Theory

Reviews of the literature on both traditional audits and Shariah audits were done to achieve the aim of the study. According to paragraph 1220.A3 on page 7 of The International Standards for the Professional Practise of Internal Auditing (ISPPIA), internal auditors "must be alert to the significant risks that might affect objectives, operations, or resources." To rephrase, Islamic banking must have internal Shariah auditors who can spot threats to the industry's goals. This is due to the fact that SNCR caused by non-compliance with Shariah principles is regarded as the most critical risk in IFIs (Mohd Noor et al., 2018; Mohamad Puad et al., 2020; Rosman et al., 2017), among the many distinct sets of hazards exposed to Islamic banking. In order to ensure the integrity of the IFI's internal controls, risk management systems, governance processes, and the overall conformity of the IFI's operations, business, affairs, and activities with Shariah, sound SNCR judgement is essential in its role as an agent to multistakeholder (i.e., Shariah committee, BAC, external auditor).

Most studies on JDM have used cognitive theory (Trotman et al., 2011). The theory is applied to assess the auditor’s task performance and ability to process information (Trotman, 1995). Therefore, the present study conceptualised the theoretical framework from many facets of SCT and JDM to determine the information processing strategies used by auditors when making decisions and judgements. Bandura (1986) proposed the social cognitive theory (SCT) to explain how and why people learn from one another and their surroundings. Personal and mental characteristics are examples of individual factors. Colleagues, clients, the weather, and so on are all examples of environmental elements that might influence an individual's actions because of their proximity to the individual. A person's behaviour is the result of a wide variety of internal and external stimuli.

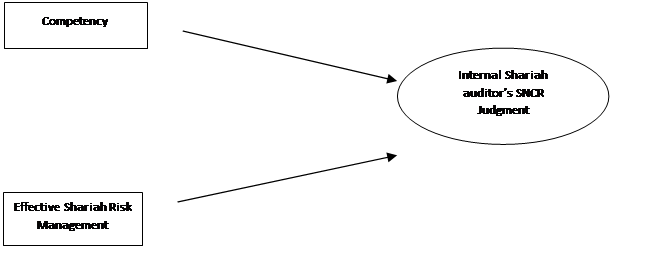

The theory suggests that people's judgements are motivated by their own internal forces and can be influenced, moulded, and controlled by their social contexts, their immediate environments, and their own unique characteristics. That is to say, both the auditor's immediate surroundings and the auditor themselves may colour their evaluation. Developing one's own capacity for self-direction is a crucial first step. The acquisition of skills that affect one's own motivation and behaviour is one example of these (Bandura, 1989). Shariah auditors put more weight on Islamic principles than their Western colleagues. Internal Shariah auditors must be well-versed in both accounting and auditing as well as Shariah, particularly Fiqh Muamalat. The internal shariah auditor's ability to put Shariah knowledge to use is greatly enhanced by his or her familiarity with Islamic financial products and businesses. The ability to anticipate new and existing dangers in a company depends in large part on the auditor's proficiency in auditing. This will give the internal Shariah auditor the skills they need to pay closer attention to details, deal effectively with auditing challenges, and convey their conclusions with assurance (Mohd Ali et al., 2020). Due to the complexity and rapid increase of knowledge, people are increasingly relying on modelled expertise to learn specialised cognitive competencies. You can learn the information and skills you need to make good decisions from people who are already experts in the field (Bandura, 1989). Internal Shariah auditors may speak with the Shariah risk and Shariah review teams as part of the planning process for the Shariah audit (Puad et al., 2020a; Yazkhiruni et al., 2018; Yasoa' et al., 2020). Shariah risk management in Islamic banks serves as an illustration of how SNCR can be reduced by utilising the proper risk management techniques and procedures. For this reason, successful completion of risk-based audits requires that internal Shariah auditors and risk management have a good working relationship. The internal Shariah auditor of an organisation might use the risk profile provided by Shariah risk management to conduct a risk-based audit, for example. Since the internal Shariah auditor's judgement performance in SNCR is dependent on the quality of the risk profile, effective Shariah risk management will improve that performance. The proposed structure is seen in Figure 1.

The purpose of the suggested framework is to learn more about the mind at work throughout the judging process. Planning, carrying out the plan, reporting on the results, and then following up all necessitate a search for relevant information. Ability of the internal Shariah auditor to identify SNCR during risk assessment sets the basis for appropriate judgement throughout the planning phase. A solid basis in both conventional assurance skills and procedures and a thorough comprehension of Shariah concepts were required to accurately assess and detect Shariah risk in a variety of financial arrangements, contracts, and transactions. As a result, the internal Shariah auditor's proficiency demonstrates their ability to understand the facts and turn it into a trustworthy audit judgement. SCT also addresses the influence of an individual's environment on their judgement. According to the guidelines of internal Shariah auditing, the SNCR internal Shariah auditors' surroundings would have an impact on the accuracy of their judgement. Bandura (1989) explains that modelled expertise helps less competent people learn the information and reasoning processes essential to make accurate judgements by allowing them to seek the help of knowledgeable and experienced experts. As a result, the internal Shariah auditor's drive to learn might be boosted by the knowledge-sharing and guidance they receive from their social network.

Conclusion and Future Research

To protect the maslahah of the ummah (public interest) and ensure that Islamic company operations and transactions are in line with Shariah, Shariah auditors must ensure that they adhere to the principles of equity and social justice. The internal Shariah auditor is the third line of defence, responsible for using professional judgement to ensure that both IFIs and Islamic banks have suitable internal control systems in place to ensure Shariah compliance. Because the internal Shariah auditor's work will be used by its intended users, the chain of reliance on it illustrates the requirement for auditors to use the greatest level of SNCR judgement to assure accuracy and reliability at all reporting levels. This study examined earlier studies, specifically with regard to SNCR, that focuses on what most affects the internal Shariah auditor's judgement.

This research reveals that an internal Shariah auditor's capacity to make competent and objective judgements in SNCR is influenced by both his individual factor (competence) and his environment factor (effective risk management). The study of SNCR judgement performance is essential because the internal Shariah auditor from the internal audit department of IFI is one of the crucial corporate governance actors whose judgements are significantly relied upon by other significant corporate governance actors. In terms of theory and structure, this research will add to the existing body of Shariah audit literature. Further study is urged to investigate the effects of the aforementioned factors on internal Shariah auditors' SNCR assessment using real-world data from IFIs such takaful companies and Islamic banks. Additional variables for the individual and environmental characteristics of the auditor may be incorporated and objectively evaluated in order to identify factors influencing the SNCR judgement performance of internal Shariah auditors.

Acknowledgments

The invaluable assistance of Dr. Fazlida Mohd Razali, and Prof. Dr. Jamaliah Said from Accounting and Research Institute (ARI) UiTM, made this research paper possible. I am also grateful for the Geran Insentif Penyeliaan (GIP) provided by Timbalan Naib Canselor (Penyelidikan dan Inovasi), UiTM.

References

Abdul Rahman, A. R. (2010). Shari’ah audit for Islamic financial services: The needs and challenges. The Journal of Muamalat and Islamic Finance Research, 7(1), 133–145. https://oarep.usim.edu.my/jspui/handle/123456789/4889

Ahmad, M. H., & Lateh, N. (2020). The development of Shariah risk management model (SRM-i) for the use of Shariah compliance organizations. Environment-Behaviour Proceedings Journal, 5(SI1), 79–84. DOI:

Alahmadi, H. A., Hassan, A. F. S., Karbhari, Y., & Nahar, H. S. (2017). Unravelling Shariah audit practice in Saudi Islamic banks. International Journal of Economic Research, 14(15), 255–269.

Alam, N. (2019). Regulatory and supervisory issues in Shariah-compliant hedging instrument. In IFSB Working Paper Series: Vol. WP-14 (Issue December).

Algabry, L., Alhabshi, S. M., Soualhi, Y., & Alaeddin, O. (2020). Conceptual framework of internal Sharīʿah audit effectiveness factors in Islamic banks. ISRA International Journal of Islamic Finance, 12(2), 171–193. DOI:

Ali, M. M., & Hassan, R. (2020). Survey on Sharīʿah non-compliant events in Islamic banks in the practice of tawarruq financing in Malaysia. ISRA International Journal of Islamic Finance, 12(2), 151–169. DOI:

Asare, S. K., Fitzgerald, B. C., Graham, L. E., Joe, J. R., Negangard, E. M., & Wolfe, C. J. (2013). Auditors' Internal Control over Financial Reporting Decisions: Analysis, Synthesis, and Research Directions. AUDITING: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 32(Supplement 1), 131-166. DOI:

Asmara, R. Y. (2017). The effects of internal auditors competence and independence on professional judgment: Evidence from Indonesia. International Journal of Economic Perspective, 11(2), 300–308.

Ayedh, A. M., Mahyudin, W. A., Abdul Samat, M. S., & Muhamad Isa, H. H. (2021). The integration of Shariah compliance in information system of Islamic financial institutions: Qualitative evidence of Malaysia. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 13(1), 37–49. DOI:

Azrak, T., Saiti, B., & Engku Ali, E. R. A. (2016). An analysis of reputational risks in Islamic banks in Malaysia with a proposed conceptual framework. Al-Shajarah, 21(3), 331–360.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundation of thought and action: A social cognitive theory (1st Ed.). Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Bandura, A. (1989). Social cognitive theory. In Annals of child development (Vol. 6). JAI Press. DOI:

Bank Negara Malaysia. (2010). Shariah Governance Framework.

Bank Negara Malaysia. (2019). Shariah Governance Policy Document. https://www.bnm.gov.my/-/policy-document-on-shariah-governance

Bonner, S. E. (1999). Judgment and decision making research in accounting. Accounting Horizons, 13(4), 385–398. DOI:

Bonner, S. E. (2008). Judgment and decision making in accounting (1st Ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

Centre for Research and Training. (2022). Shariah Auditing : Structure and Process. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VWrSXjSZwX4

COSO. (2004). Enterprise Risk Management — Integrated Framework Executive Summary. In New York (Vol. 3, Issue September, pp. 1–16). http://www.coso.org/documents/COSO_ERM_ExecutiveSummary.pdf

Deliu, D. (2020). Elevating Professional Reasoning in Auditing. Psycho-Professional Factors Affecting Auditor's Professional Judgement and Skepticism. Journal of Accounting and Auditing: Research & Practice, 2020, 1-17. DOI:

Dickinson, A. (2010). Interfacing risk management and internal audit - Conflicting or complementary ? Journal of Chartered Secretaries Australia Ltd, 6(7), 412–418.

Elgari, M. A. L. I. (2003). Credit risk in Islamic banking and finance. Islamic Economic Studies, 10(2), 2007–2008.

Hanefah, M. M., Shafii, Z., Salleh, S., Zakaria, N., & Kamaruddin, M. I. H. (2020). Governance and Shariah audit in Islamic financial institutions (2nd ed.). USIM Press.

Hassan, R. (2016). Shariah non-compliance risk and its effects on Islamic financial institutions. Al-Shajarah: Journal of the International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization (ISTAC), 21(3), 21–25. https://journals.iium.edu.my/shajarah/index.php/shaj/article/view/411

Institute of Internal Auditors. (2016). International standards for the professional practice of internal auditing (Standards).

Isa, F. S., Ariffin, N. M., Hafizah, N., & Abidin, Z. (2020). Shariah audit practices in Malaysia: Moving forward. Journal of Islamic Finance, 9(2), 42–58.

Iskandar, T. M., & Sanusi, Z. M. (2011). Assessing the effects of self-efficacy and task complexity on internal control audit judgment. Asian Academy of Management Journal of Accounting and Finance, 7(1), 29–52.

Islam, K. M. A., & Bhuiyan, A. B. (2021). Determinants of the Effectiveness of Internal Shariah Audit: Evidence from Islamic Banks in Bangladesh. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8(2), 223–230. DOI:

Islamic Financial Service Board. (2005). Guiding principles of risk management for institutions (other than insurance institutions) offering only Islamic financial services (Issue December). https://www.ifsb.org/published.php

Kasim, N., & Sanusi, M. Z. (2013). Emerging issues for auditing in Islamic financial institutions: Empirical evidence from Malaysia. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 8(5), 10–17. DOI:

Kasim, N., Ibrahim, S. H. M., & Sulaiman, M. (2009). Shariah auditing in Islamic financial institutions: Exploring the gap between the “desirable” and the “actual.” Global Economy & Finance Journal, 2(2), 127–137. http://irep.iium.edu.my/13560/

Khalid, A. A., & Sarea, A. M. (2019). Factors Influencing Internal Shariah Audit Effectiveness: Evidence From Bahrain. International Journal of Financial Research, 10(6), 196. DOI:

Khalid, A. A., Haron, H. H., & Masron, T. A. (2017). Relationship between internal Shariah audit characteristics and its effectiveness. Humanomics, 33(2), 221–238. DOI:

Khalid, A. A., Haron, H., & Masron, T. A. (2018). Competency and effectiveness of internal Shariah audit in Islamic financial institutions. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 9(2), 201–221. DOI:

Khan, M. A. (1985). Role of the auditor in an Islamic economy. Journal of Research in Islamic Economics, 3(1), 31–41.

Khatib, S. F. A., Abdullah, D. F., Al Amosh, H., Bazhair, A. H., & Kabara, A. S. (2022). Shariah auditing: analyzing the past to prepare for the future. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 13(5), 791-818. DOI:

Lahsasna, A. (2016). Shariah audit in Islamic finance (1st ed.). IBFIM.

Libby, R., & Luft, J. (1993). Determinants of judgment performance in accounting settings: Ability, knowledge, motivation, and environment. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 18(5), 425–450. DOI:

Mala, R., & Chand, P. (2015). Judgment and Decision-Making Research in Auditing and Accounting: Future Research Implications of Person, Task, and Environment Perspective. Accounting Perspectives, 14(1), 1-50. DOI:

Miledi, A. (2022). The construction of audit partner’s judgment. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 20(1), 24–52. DOI:

Mohamad Puad, N. A., Abdullah, N. I., & Shafii, Z. (2020). Follow Up in Shariah auditing : Multiple approaches by takaful operators. International Journal of Islamic Economics and Finance Research, 3(1), 14–29.

Mohamed, S., Goni, A., Alanzarouti, F., & Taitoon, J. (2020). ICD-REFINITIV Islamic finance development report 2020: Progressing through adversity.

Mohd Ali, N. A., & Kasim, N. (2019). Talent management for Shariah auditors: Case study evidence from the practitioners. International Journal of Financial Research, 10(3), 252–266. DOI:

Mohd Ali, N. A., Shafii, Z., & Shahimi, S. (2020). Competency model for Shari’ah auditors in Islamic banks. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 11(2), 377–399. DOI:

Mohd Noor, N. S., Ismail, A. G., & Mohd. Shafiai, M. H. (2018). Shariah Risk: Its Origin, Definition, and Application in Islamic Finance. SAGE Open, 8(2), 215824401877023. DOI:

Najeeb, S. F., & Ibrahim, S. H. M. (2014). Professionalizing the role of Shari'ah auditors: How Malaysia can generate economic benefits. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 28, 91-109. DOI:

Omar, H. N., & Hassan, R. (2019). Shariah non-compliance treatment in Malaysian Islamic banks. International Journal of Management and Applied Research, 6(4), 220–233. DOI:

Puad, N. A. M., Shafii, Z., & Abdullah, N. I. (2020a). Challenges in Shariah audit practices from the lense of practitioners: The case of Malaysian takaful industry. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(16), 378–388. DOI:

Puad, N. A. M., Shafii, Z., & Abdullah, N. I. (2020b). The practices of risk-based internal Shariah auditing within Malaysian takaful operators: A multiple case study. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 10(7), 52–71. DOI:

Rashid, A., & Ghazi, M. S. (2021). Factors affecting Sharīʿah audit quality in Islamic banking institutions of Pakistan: A theoretical framework. Islamic Economic Studies, 28(2), 124–140. DOI:

Razali, F. M. (2020). Examining Types of Audit Judgment and Objectivity Threat: Empirical Findings from Public and Private Sector Internal Auditors in Malaysia. Indonesian Journal of Economics, Social, and Humanities, 2(2), 91-104. DOI:

Rosman, R., Che Azmi, A., & Amin, S. N. (2017). Disclosure of Shari’ah non-compliance income by Islamic banks in Malaysia and Bahrain. International Journal of Business and Society, 18(S1), 45–58.

Sani, S. D., & Abubakar, M. (2021). A proposed framework for implementing risk-based Shari'ah audit. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 19(3), 349-368. DOI:

Selim, G., & McNamee, D. (1999). The Risk Management and Internal Auditing Relationship: Developing and Validating a Model: The Risk Management and Internal Auditing Relationship. International Journal of Auditing, 3(3), 159-174. DOI:

Shafiq, M. (1984). The meaning of ra’y and nature of its usage in Islamic law (An examination of select cases of the legal reasoning in the period of ’ Umar , the second caliph). Islamic Studies, 23(1), 21–32.

Sulaiman, N., Hannan, M. A., Mohamed, A., Ker, P. J., Majlan, E. H., & Wan Daud, W. R. (2018). Optimization of energy management system for fuel-cell hybrid electric vehicles: Issues and recommendations. Applied Energy, 228, 2061-2079. DOI:

Sultan, S. A. M. (2007). A Mini Guide to Shari’ah Audit for Islamic Financial Institutions. CERT Publications Sdn Bhd.

Trotman, K. T. (1995). Research Methods for Judgment and Decision Making Studies in Auditing. Coopers and Lybrand.

Trotman, K. T. (1998). Audit judgment research-Issues addressed, research methods and future directions. Accounting and Finance, 38(2), 115-156. DOI:

Trotman, K. T., Tan, H. C., & Ang, N. (2011). Fifty-year overview of judgment and decision-making research in accounting. Accounting & Finance, 51(1), 278-360. DOI:

Wedemeyer, P. D. (2010). A discussion of auditor judgment as the critical component in audit quality - A practitioner's perspective. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 7(4), 320-333. DOI:

Wehr, H. (1976). A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic. Librairie du Liban.

Yaacob, H., & Donglah, N. K. (2012). Shari’ah audit in Islamic financial institutions: The postgraduates’ perspective. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 4(12). DOI:

Yahya, Y., & Mahzan, N. (2012). The Role of Internal Auditing in Ensuring Governance in Islamic Financial Institution (IFI). 3rd International Conference on Business and Economic Research (3rd ICBER 2012) Procceding, March, 1634–1661.

Yasoa', M. R., Wan Abdullah, W. A., & Endut, W. A. (2020). The Role of Shariah Auditor in Islamic Banks: The Effect of Shariah Governance Framework (SGF) 2011. International Journal of Financial Research, 11(4), 443. DOI: 10.5430/ijfr.v11n4p443 3

Yazkhiruni, Y., Nurmazilah, M., & Haslida, A. H. (2018). A Review of Shariah Auditing Practices in Ensuring Governance in Islamic Financial Institution (IFIs)-A Preliminary Study. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 5(7), 196–210.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

15 November 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-130-0

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

131

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1281

Subjects

Technology advancement, humanities, management, sustainability, business

Cite this article as:

Ahmad, A., Razali, F. M., & Said, J. (2023). Determinants of Shariah Non-Compliance Risk Judgment Among Shariah Auditors. In J. Said, D. Daud, N. Erum, N. B. Zakaria, S. Zolkaflil, & N. Yahya (Eds.), Building a Sustainable Future: Fostering Synergy Between Technology, Business and Humanity, vol 131. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 378-394). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2023.11.31