Abstract

The digital financial services (DFS) advancement alters Malaysia’s financial landscape and fosters financial inclusion (FI) among young people which could help to improve their resilience in financial shocks. In this regard, this research warrants a growing need for a framework to address young consumers’ financial behaviour in accessing digital financial products to reveal stylized facts on their usages pattern. The concept of “digital financial literacy” (DFL) needs to suit Shari’a guidelines to ensure that financial services are aligned with individual needs. This called for the need to strengthen DFL by investigating the elements of DFL in the Malaysia context. Thus, this research will focus on the implications of DFL towards financial behaviour through causal testing methods and will come out with a framework for DFL that complies with Shari’a guidelines. The proposed output will make significant contributions to academia (extend the literature on DFL); industry (DFL framework that complies with Shari’a); government (policies of DFL and FI governance); community (promote young adults financial well-being that can enhance their integrity to avoid corruptions); and environment (a quality digital financial environment that navigates the communication of DFL to our young adults for their future resilient growth).

Keywords: Digital Financial Literacy, Financial Inclusion, Shari’a Guidelines, Young Adults

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic brought a significant effect on consumers’ spending behaviours. The enforcement of the Movement Control Order (MCO) and recommendation of social distancing have made contactless digital payments widely adopted in Malaysia. A study by Mastercard 2020 indicated the shifting lifestyle in terms of e-wallet payment methods among consumers in Southeast Asia. Malaysia recorded the most usage of digital wallets at 40 per cent from a total of 10,000 consumers across the Asia Pacific Region. The Oppotus posted statistics of Malaysian digital wallet usage has increased from year to year, especially during the pandemic time. Along with the government introduction of incentives schemes under e-Penjana, the usage of digital wallets raised to 60 per cent in the 3rd quarter of 2020. In the subsequent year, digital wallet usage raised again to 66 per cent in the 3rd quarter of 2021 and maintained almost 67 per cent in yearly usage. According to the report, Generation Y (age range 18- 24 years old) and Generation X (age range 25-39 years old) were active users of digital wallets.

Significant digital wallet usage in the younger generation signified the younger generation has been more engaged in the digital financial economy. Due to the gig economy that mushroomed among younger generations, digital financial was important to keep track of their savings and expenses and allowed one to track their financial transactions closely. Financial digitalisation was the key to fostering greater FI in the Malaysian young generation. The growth in digital financial services (DFS) came with consumer risks exposed to frauds such as unauthorized use of data, phishing, hacker attacks, or discriminatory treatments. Moreover, along with the significant usage of e-commerce platforms, mis-selling issues, and scam issues were potentially threatening the consumers’ benefits in the marketplace. The introduction of microcredit via online platforms such as Shopee Pay Later, Grab Pay Later, and investment platforms such as eToro induced concerns of behavioural issues, such as excessive borrowing and poor investment behaviours that could cause serious financial problems among the users.

The evolution in financial services required the terms of financial literacy to include more than just the knowledge and skills regarding traditional financial services. The DFL, a combination of financial literacy and digital literacy, was introduced as a new concept (Alliance for Financial Inclusion, 2021). Although the Alliance for Financial Inclusion (2021) has defined DFL and provided important guidance notes, no specific indicators to assess the level of DFL have been proposed so far.

Past studies generally assessed financial literacy alone on the adoption and usage of DFS rather than integrating the concepts between financial literacy and digital literacy in the digital finance domain (Königsheim et al., 2017; Kass-Hanna et al., 2022; Li et al., 2020; Morgan & Trinh, 2019; Yoshino et al., 2020). However, previous research examined the adoption of specific digital financial behaviour such as internet banking behaviour (Andreou & Anyfantaki, 2021), cashless payment behaviour (Świecka et al., 2021), digital credit (Wamalwa et al., 2019) and other fintech products such as insurance (Morgan & Trinh, 2019). Although past studies emphasised more on DFL, however, the definitions and measurements of the proposed DFL are not fully captured by the suggested definition of financial literacy by OECD (2018) which included aspects of awareness, knowledge, skills, and attitude behaviour of financial literacy in digital finance domains, and the studies were not focused on youth populations (Azeez & Akhtar, 2021; Liew et al., 2020; Prasad et al., 2018). To date, there are limited studies that defined and proposed the measurement of DFL for youth comprehensively.

The Alliance for Financial Inclusion (2021) proposed to see DFL from behavioural insights in the youth population to understand the knowledge and risks of a wide array of DFS that are relevant to targeted youth segments. Therefore, this study aims at investigating young adults’ DFL in a comprehensive manner that includes, awareness, knowledge, skills, attitude, and behaviour in access to a wide range of DFS that is relevant for targeted youth segments.

Malaysia has more than 60% Muslim population and there was a 20 per cent Islamic banking market share of the total banking sector (Antara & Musa, 2020). Hence, DFL for conventional-based financial products was unable to fully capture young Muslim financial awareness, knowledge, skill, attitude, and behaviour in the digital financial market. Thus, DFL should integrate Islamic finance concepts to understand the fundamentals of Islamic financial information that exists in the digital financial market in order to make appropriate Islamic financial decisions. The Alliance for Financial Inclusion (2021) proposed to explore opportunities for the operations of relevant or related stakeholders within the digital financial ecosystem. This indicated that in a country that practising Islamic Finance (ecosystem) where Islamic Finance principles were embedded in the digital financial service ecosystem, the assessment of DFL should include the Islamic Finance concept to understand young adults’ awareness, knowledge, skills, attitude, and behaviour in accessing to DFS offered in Malaysia. In essence, this study addresses the gap by proposing a guideline for DFL that complies with Shari’a guidelines in the Malaysia context.

Literature Review

Financial inclusion (FI) for young adults

Financial inclusion (FI) plays a crucial role in promoting inclusive development and serves as a vital catalyst for numerous Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Nevertheless, almost half of the world’s young adults (aged from 15 to 24 years old) are financially excluded (OECD, 2020). The ongoing financial exclusion of youth has adverse effects on individuals, communities, and the overall economy. It is crucial to strategically enhance FI for young adults as it empowers them to achieve financial independence and improves their financial well-being based on their specific needs and life stage.

Financial habits start from young. Past studies indicated that individual financial behaviour influences childhood. According to a study by Whitebread and Bingham (2013), individuals begin forming their financial habits as early as seven years old, and their perspectives on financial matters continue to evolve throughout various stages of life. Young individuals go through distinct life stages, starting as adolescents with financial pressures primarily centred around their education and, later transitioning into young adulthood where they face increased financial responsibilities in supporting their household and eventually establishing their own family. The transitions of life stages require distinct approaches and support from policy to ensure the effectiveness of FI of young adults.

Anderson et al. (2019) differential three life stages of young adults and their financial needs. In particular, the three stages are early adolescence refers to age (12-14 years old), late adolescence age at (15-17 years old) and young adulthood age at (18-24 years old). Early adolescence and late adolescence were likely depending on parents or guardians to meet their needs. At these ages, education was their main concern, and they have lesser financial pressure compared to other life stages. On the other hand, the period of young adulthood, spanning from 18 to 24 years old, is often considered the most challenging stage. At this stage, the transition to adulthood required them to take up some responsibilities, such as contributing to household income, fulfilling basic needs, paying education fees and likely to start earning income to pay bills and fulfilling wants.

The FI for young adults was important in Malaysia. Essentially, during the age range of 18 to 24 years old, young individuals begin to explore FI through avenues such as savings, educational insurance, life policies, and access to educational loans. These financial tools enable youth and their families to invest in their education. Access to financial services can also strengthen young adults’ financial behaviour by providing ways for them to manage their money. Despite the access to financial services, solid financial management knowledge and skills together with financial tools are crucial for young adults to make viable financial decisions and become more resilient to financial shocks. Hence, financial literacy is viewed as a strategic effort to enhance young adults’ FI because it helps to strengthen economic resilience over the long term.

Behavioural finance and digital literacy to understand digital financial literacy (DFL)

Behavioural finance was the branch of financial discipline that investigates individual behaviour in the financial market and the human psychological factors in financial decisions making (Madi & Yusof, 2018). In fact, behavioural finance was part of personal finance that explains individual financial behaviour in managing sources of funds or money through evaluating the potential of loss and gain in relation to financial products (Beverly et al., 2003). Behavioural finance was different compared to the classical theory that insists on a rational decision-making model in an efficient market (Josef & Vera, 2017). The general assumption of behavioural finance was financial decision-making was influenced by an individual's characteristics and information structure and then significantly influenced by the financial market. In this regard, an ideal situation of an effective market did not exist as individuals in the market were not always fully rational in making the best financial decision.

Behavioural finance revealed the facts of individuals’ financial decisions. Simon (1957) coined the term “bounded rationality” to describe cognitive limitations in decision-making. From this perspective, individuals did not engage in a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis to ascertain the most advantageous decisions but depended on the limited information and cognitive capability to make a “satisfied” decision rather than an optimal decision. By including human features in financial decision-making, behavioural finance seeks to explain how individuals make satisfying financial decisions based on “bounded rationality” characteristics. Josef and Vera (2017) argued that an individual's characteristics were the key to determining their financial decision. This suggests that an individual's characteristics (financial awareness, knowledge, skills and attitudes) were important in empowering financial consumers to make informed decisions within the marketplace.

Financial literacy referred to “a combination of awareness, knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviour necessary to make sound financial decisions and ultimately achieve individual financial well-being” (OECD, 2020, p. 27). In other words, financial literacy was an individual's characteristics that determine their financial decisions and results in financial behaviours that enhance well-being, such as engaging in financial planning, being aware of risk, saving, using credit responsibly, and making appropriate choices regarding other financial products. In the competitive market, financial decisions were subjected to varied risks, especially in cash and liquidity decisions (Madi & Yusof, 2018). Therefore, individuals needed to be aware of financial market risks, have sufficient knowledge and skills in financial services, and with positive attitude and behaviour to manage money to avoid the risks that will cause a loss in case and liquidity.

Financial literacy in DFS had a different context compared to traditional financial services. Literacy in finance alone is not enough to capture the new technologies element in the financial market. Digital literacy was needed for individuals to be aware of DFS, also, for acquiring knowledge and skills on using DFS. Digital literacy, as defined by the Museum and Library Services Act of 2010 (Authenticated U.S. Government Information, 2010), refers to the proficiency in utilising technology to facilitate users in finding, evaluating, organising, creating, and communicating information. It encompasses the development of digital citizenship and responsible technology use. In the context of the financial market, digital literacy pertained to the skills required to leverage technology for discovering, assessing, organising, creating, and communicating information regarding financial services available in the digital realm.

The concepts of digital literacy and financial literacy were interconnected and shared some common ground with the concept of information literacy. Information literacy referred to an individual's capacity to identify, assess, and efficiently utilise relevant information. As technology has been employed to organise and distribute financial information, financial literacy has become more intricate and encompassing. Indeed, the ability to utilize multiple digital resources to gather information, be aware and recognize the value of information, and acquire knowledge and skills to transform and use the information to make sound financial decisions is challenging as it is needed both for digital literacy and financial literacy. In other words, DFL is the amalgamation of digital literacy and financial literacy. Individuals possessing DFL possessed a comprehensive understanding of digital financial products and services, were cognisant of digital financial risks, possessed knowledge of how to mitigate such risks, and are aware of consumer rights (Morgan et al., 2019).

Method

Conceptual framework for digital financial literacy (DFL)

Based on concepts of financial literacy and digital literacy, this study constructs multidimensional DFL by linking specific dimensions and impacts of digital literacy within the context of financial literacy. Moreover, given that Malaysia is practising Islamic finance, this study integrates Islamic principles in financial literacy within the digital financial service context to construct a measurement framework that is suitable in the Malaysia context.

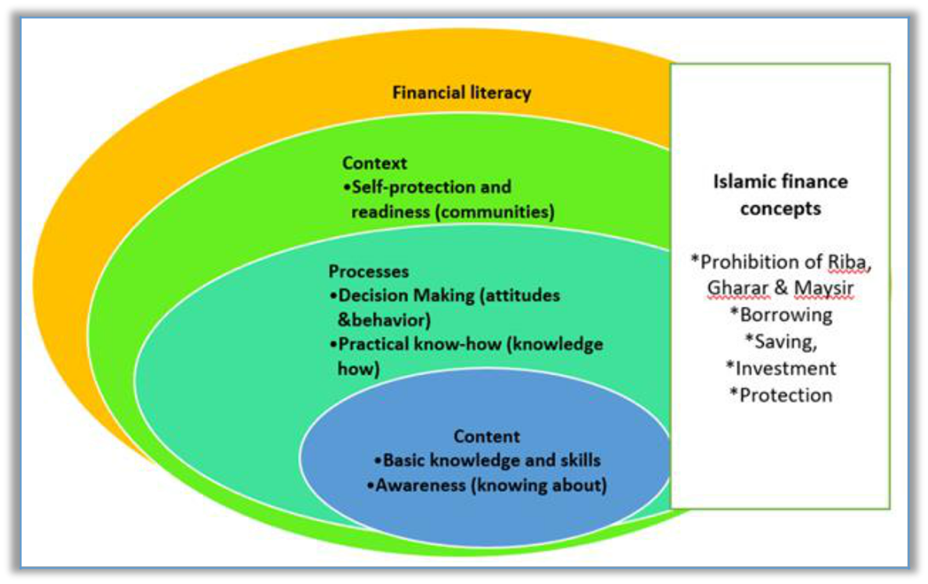

This study initiated a theoretical exploration of financial literacy, Islamic fundamental knowledge and digital literacy as distinct concepts. It subsequently established a conceptual framework that interconnects these concepts, formally illustrates the relationship between financial literacy, Islamic fundamental knowledge, and digital literacy. First, this study linked financial literacy with Islamic fundamental knowledge in finance to tackle financial literacy on Shari’a compliance finance products. Based on OECD (2017), the proposed 3 main domains were content, processes and context and the model linking financial literacy and Islamic finance concept was built as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows the financial literacy was linked with Islamic finance concepts.

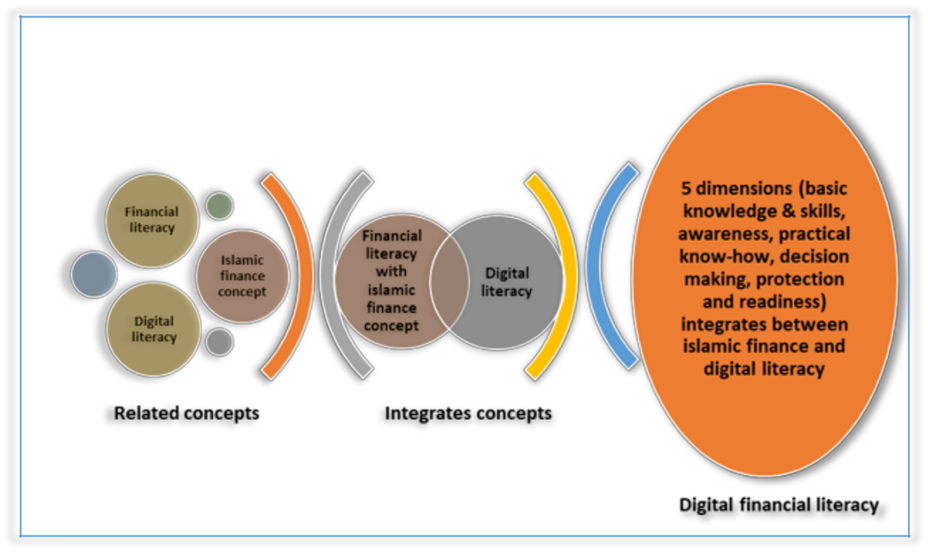

Figure 2 illustrates a model linking financial literacy with the Islamic finance concept and digital Literacy.

Research design

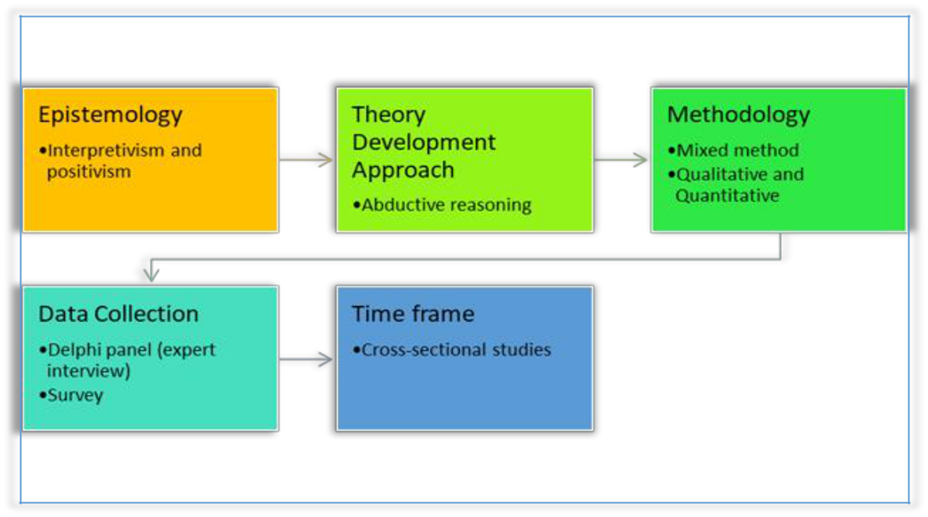

The Figure 3 illustrates the research design. In accordance with an explanatory sequential design (Creswell & Clark, 2017), this study employed qualitative data collection methods to enhance the comprehension of survey findings. Specifically, interviews were conducted to provide additional insights and delve into the origins of financial literacy incorporating Islamic concepts, as well as DFS literacy. Figure 4 illustrates the mixed-method design of the study.

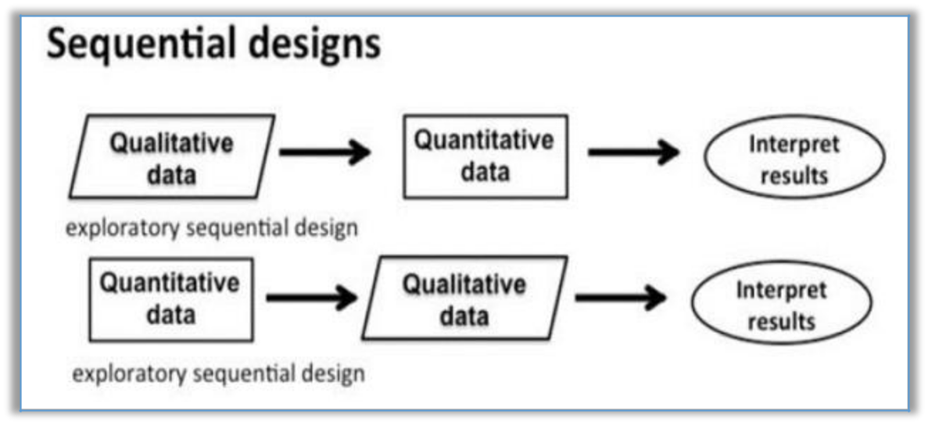

Figure 4 illustrates the mixed method design. This research applied exploratory sequential design, obtaining qualitative data then followed by quantitative data in this study. During the initial stages of instrument development, Delphi method were employed to establish the construct and ensure content and face validity. A panel of experts was consulted to examine the content validity, reviewing and refining the items for clarity (Mitchell, 2020). By engaging experts with expertise in the specific domains relevant to the research area, valuable input was obtained for item generation. Simultaneously, the panel’s feedback served as evidence supporting the items’ content validity and face validity.

The subsequent phase of instrument development involved pilot testing the instruments derived from the Delphi method, followed by the administration of surveys employing quantitative approaches, such as factor analysis, to collect evidence of construct validity, including convergent validity and discriminant validity. Statistical item analysis and factor analysis were employed to gather evidence for construct validity (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2010). Exploratory factor analysis, utilizing principal components' extraction, was conducted to identify factors, reduce the number of items, and assess the factor structure (Hurley et al., 1997). Confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS was then employed to validate the factor structure identified through exploratory factor analysis (Shek & Yu, 2014). When the model fit indices met the acceptable criteria, it provided evidence for construct validity, indicating that the items effectively measured the intended scale construct.

Discussion

Digital financial services (DFS) and young adults

New technologies have transformed the business models and reforms of the financial services landscape of the world. Along with the development in mobile phone usage, DFS come in places and reach significant scale usages in some countries (Kim, 2020). The DFS cover a wide array of financial offerings that are accessed and delivered through digital platforms such as mobile channels, ATMS, point-on-sale (POS) terminals, and other similar means (Bansal, 2019). The services include payments, credit, savings, remittances, insurance, and others (Alliance for Financial Inclusion, 2016). OECD (2017) defined DFS as:

Financial operations using digital technology, including electronic money, mobile financial services, online financial services, i-teller and branchless banking, whether through the bank or non-bank institutions. DFS can encompass various monetary transactions such as depositing, withdrawing, sending and receiving money, as well as other financial products and services including payment, credit, saving, pensions and insurance. DFS can also include non-transactional services, such as viewing personal financial information through digital devices. (pp. 10)

Past research indicated that digital financial inclusion was the supply of DFS filling the gap left by traditional financial institutions (Khera et al., 2021). In fact, the inefficiency of traditional financial services is the driver for DFS usage. People go for fintech where the traditional financial institution is unable to provide services that are suited to individual needs. According to a report by the OECD (2020), the digitisation of finance presents an opportunity to enhance FI by extending the accessibility of financial services. This benefits individuals who were previously unbanked, offering them more convenient, faster, secure and time-saving transactions. Additionally, DFS can provide tailored services that meet individual needs.

Young adults aged 18-24 years old were the group that have significant interaction with digital technologies compared to older generations. UNICEF (2017) reported 71% of young people from the total population was online and this indicates the potential of DFS among young people. As young people were more technology savvy, DFS have the capacity to improve young people’s FI by providing reachable financial services and making financial services less costly compared to traditional financial services (Alliance for Financial Inclusion, 2021).

Digital financial literacy (DFL) and young adults

In the digital era, the DFL was poised to gain growing significance for young adults. However, Alliance for Financial Inclusion (2021) reported that many young adults have the perception that they do not need financial services. The main reasons for the perception that no need for financial services was due to fewer resources and assets, low exposure and experience with formal financial services, and most important lack of financial literacy. Insufficient financial literacy, particularly in the realm of digital financial systems, has heightened the vulnerability of customers to various risks such as phishing schemes, data theft, and excessive indebtedness (OECD, 2020). Vulnerability hinders young adults from using DFS and causes a lack of trust in DFS. Therefore, understanding of using DFS is important to encourage young adults’ digital financial inclusion.

Digital financial literacy (DFL) and Islamic finance

Malaysia has more than 60% Muslim population and there was 20% Islamic banking market share of the total banking sector (Antara & Musa, 2020). Hence, DFL for conventional-based financial products was unable to fully capture young Muslim financial awareness, knowledge, skill, attitude and behaviour in the digital financial market. Thus, DFL should integrate Islamic finance concepts to understand the fundamentals of Islamic financial information in the digital financial market.

Conclusion

This study aims to contribute to the existing literature on DFL by incorporating the novel value-assess of Shari'a elements in DFL. By integrating Islamic finance into DFL indicators, a more comprehensive assessment of the digital financial system in Malaysia can be achieved. This development and validation of DFL indicators will serve as a benchmark for assessing the level of DFL and facilitate better FI among young adults in Malaysia. For example, by including Islamic finance principles in DFL indicators, the assessment can encompass areas such as understanding Islamic banking products, knowledge of halal investment options, and awareness of ethical considerations in financial transactions. This broader perspective not only acknowledges the specific financial needs and preferences of individuals in a predominantly Muslim country like Malaysia but also contributes to promoting inclusive and culturally sensitive financial practices.

Acknowledgments

This work is ostensibly supported, financially and/or non-financially, directly and/or indirectly by the School of Government, UUM COLGIS, Universiti Utara Malaysia that encourages collaborative participation between the academics, alumni, and industry.

References

Alliance for Financial Inclusion. (2016). Digital financial services: Basic terminology. https://www.afi-global.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/2016-08/Guideline%20Note-19%20DFS-Terminology.pdf

Alliance for Financial Inclusion. (2021). Digital financial literacy. https://www.afi-global.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/AFI_Guideline45_Digi_Finance_Literacy_aw5.pdf

Anderson, J., Hopkins, D., & Valenzuela, M. (2019, June). The role of financial services in youth education and employment [Working paper]. World Bank. https://www.cgap.org/research/publication/role-of-financial-services-in-youth-education-and-employment

Andreou, P. C., & Anyfantaki, S. (2021). Financial literacy and its influence on internet banking behavior. European Management Journal, 39(5), 658-674. DOI:

Antara, P. M., & Musa, R. (2020). Validating Islamic financial literacy instruments among mum generation: Rasch analysis approach. International Journal of Business and Society, 21(3), 1113-1121.

Authenticated U.S. Government Information. (2010). Pub. L. No. 111-340, 124 Stat. 3594. Museum and Library Services Act of 2010. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-111publ340/pdf/PLAW-111publ340.pdf

Azeez, N. P. A., & Akhtar, S. M. J. (2021). Digital financial literacy and its determinants: An empirical evidences from rural India. South Asian Journal of Social Studies and Economics, 11(2), 8-22. DOI:

Bansal, R. (2019). Recent trend in mobile banking in Indian markets. International Journal of Electronic Banking, 1(4), 317-328. DOI:

Beverly, S. G., Hilgert, M. A., & Hogarth, J. M. (2003). Household financial management: The connection between knowledge and behavior. Federal Reserve Bulletin, 89(1), 309-322.

Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage Publications.

Hurley, A. E., Scandura, T. A., Schriesheim, C. A., Brannick, M. T., Seers, A., Vandenberg, R. J., & Williams, L. J. (1997). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: Guidelines, issues, and alternatives. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18(6), 667-683. DOI: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1379(199711)18:6<667::aid-job874>3.0.co;2-t

Josef, N., & Vera, J. (2017). Financial literacy and behavioural skills: The influence of financial literacy level on behavioural skills. KnE Social Sciences, 1(2), 366-373. DOI:

Kass-Hanna, J., Lyons, A. C., & Liu, F. (2022). Building financial resilience through financial and digital literacy in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Emerging Markets Review, 51(1), 1-28. DOI:

Khera, P., Ng, S. Y., Ogawa, S., & Sahay, R. (2021, June). Is digital financial inclusion unlocking growth? (IMF Working Papers No. 167). DOI:

Kim, Y. R. (2020). Digital services tax: A cross-border variation of the consumption tax debate. Alabama Law Review, 72(371), 131-185.

Königsheim, C., Lukas, M., & Nöth, M. (2017). Financial knowledge, risk preferences, and the demand for digital financial services. Schmalenbach Business Review, 18(4), 343-375. DOI:

Li, Y., Li, Z., Su, F., Wang, Q., & Wang, Q. (2020). Fintech penetration, financial literacy, and financial decision-making: Empirical analysis based on tar. Complexity, 2020(1), 1-12. DOI:

Liew, T. P., Lim, P. W., & Liu, Y. C. (2020). Digital financial literacy: A case study of farmers from rural areas in Sarawak. International Journal of Education and Pedagogy, 2(4), 245-251.

Madi, A., & Yusof, R. M. (2018). Financial literacy and behavioral finance: Conceptual foundations and research issues. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 9(10), 81-89.

Mitchell, K. M. (2020). The theoretical construction and measurement of writing self-efficacy. [Doctoral thesis, University of Manitoba]. MSpace. https://mspace.lib.umanitoba.ca/items/cf62ec13-a303-4553-8eee-af2d5ba35dca

Morgan, P. J., Huang, B., & Trinh, L. Q. (2019). The need to promote digital financial literacy for the digital age. The future of work and education for the digital age. In Realizing Education for All in the Digital Age (pp. 40-46). Asian Development Bank Institute. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/503706/adbi-realizing-education-all-digital-age.pdf

Morgan, P., & Trinh, L. Q. (2019). Fintech and financial literacy in the Lao PDR. SSRN Electronic Journal, 933(1), 1-23. DOI:

OECD. (2017). Students’ financial literacy.

OECD. (2018). Toolkit for measuring financial literacy and financial inclusion. https://www.oecd.org/financial/education/2018-INFE-FinLit-Measurement-Toolkit.pdf

OECD. (2020). International survey of adult financial literacy. https://www.oecd.org/financial/education/oecd-infe-2020-international-survey-of-adult-financial-literacy.pdf

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Bustamante, R. M., & Nelson, J. A. (2010). Mixed research as a tool for developing quantitative instruments. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 4(1), 56-78. DOI:

Prasad, H., Meghwal, D., & Dayama, V. (2018). Digital financial literacy: A study of households of Udaipur. Journal of Business and Management, 5(1), 23-32. DOI:

Shek, D. T. L., & Yu, L. (2014). Confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS: A demonstration. International Journal on Disability and Human Development, 13(2). DOI:

Simon, H. A. (1957). Models of man, social and rational: Mathematical essays on rational human behaviour in a social setting. Wiley.

Świecka, B., Terefenko, P., Wiśniewski, T., & Xiao, J. (2021). Consumer financial knowledge and cashless payment behavior for sustainable development in Poland. Sustainability, 13(11), 6401-6419. DOI:

UNICEF. (2017). The state of the world’s children 2017: Children in digital world. https://www.unicef.org/reports/state-worlds-children-2017

Wamalwa, P., Rugiri, I. W., & Lauler, J. (2019, August). Digital credit, financial literacy and household indebtedness (KBA Centre for Research on Financial Markets and Policy Working Paper Series No. 38). https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/249539/1/WPS-38.pdf

Whitebread, D., & Bingham, S. (2013). Too much, too young. New Scientist, 220(2943), 28-29. DOI:

Yoshino, N., Morgan, P. J., & Long, T. Q. (2020, March). Financial literacy and fintech adoption in Japan (ADBI Working Papers No. 1095). https://www.adb.org/publications/financial-literacy-fintech-adoption-japan

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

29 November 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-131-7

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

132

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-816

Subjects

Accounting and finance, business and management, communication, law and governance

Cite this article as:

Low, K. C., Chong, S. L., Mohamad, S. S., & Arshad, R. (2023). Digital Financial Literacy Among Young Adults in Malaysia. In N. M. Suki, A. R. Mazlan, R. Azmi, N. A. Abdul Rahman, Z. Adnan, N. Hanafi, & R. Truell (Eds.), Strengthening Governance, Enhancing Integrity and Navigating Communication for Future Resilient Growth, vol 132. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 391-401). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2023.11.02.29