Abstract

The purpose of our research is to study the referential and semiotic nature of a subject as the main medium of information in any text. We clearly distinguish the syntactic subject, which determines the structural side of the formation and functioning of the communicative units of various complexities. The paper is devoted to the study of the rules of influence of the subject not only within the framework of a sentence, but also within the broad text, which have so far attracted only minor attention of researchers. It considers the unusual pattern of functioning of the subject based on the preservation and transfer of subject information used in any sentence. Subject information refers to agent semantics, which, unlike the characteristics of a patient, does not depend on the position at the beginning or inside a sentence, and is also supported at the level of a wide text, i.e. superphrasal unity. The study also considers the possibility of using existing data and obtaining new information on the formal and semantic valence of subject (text-forming) elements in the process of teaching cross-lingual communication, as well as in the field of further development of text array referencing based on the use of programming languages, for example, Python.

Keywords: Consciousness, learning, reference, subject, semiotics

Introduction

The main distinguishing feature of denotative names (subject names) as the nominal elements of a text is the direct referential or coreferential correlation with the designated object on the one hand, and from the point of view of structure – the independent position of denotative names in a sentence and, as a rule, their correlates at the text level. The noted characteristic qualities are mainly inherent in the subject elements in the position of a subject.

Problem Statement

We will try to show how the syntagmatic structure of a subject affects the semantics of the sentence components of the corresponding nominative chains and, conversely, what effect the referential-semantic (denotative-designative) content of nominal and accompanying verb nominations has on the strength and duration of the nominative chains.

Research Questions

To study the semantic-syntactic nature of a noun as part of speech.

- The main task of this chapter is to study the features of categorization of connecting nouns that are part of the rigid subject-predicate and subject-object structure of a sentence.

- It seems relevant to formalize the laws of the formation of the text continuum taking into account the characteristics, first of all, of the names of nouns that perform the function of a subject characterized by the most complete volume of semantic and referential subject-situational information.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study is to show how the syntagmatic structure of a subject affects the semantics of the sentence components of the corresponding nominative chains and, conversely, what effect the referential-semantic (denotative-designative) content of nominal and accompanying verb nominations has on the strength and duration of the nominative chains.

Research Methods

It is worth noting the need to use the text method to study two main factors that determine the special role of a noun in the structure of an elementary sentence in terms of the possibility of increasing the volume of a sentence: the ability of the noun (and its group) to act:

- in the function of other members of a sentence, i.e. the ability of this group to be reused in the same elementary sentence and the formal ability of the noun group to theoretically unlimited growth.

Findings

It seems unlikely that the status of a subject of such importance for French and many other languages would not play any other role than purely conditional and superficial in the language. The possibility that the status of a subject plays an important substantive role should not be rejected, so the work suggests that the subject has a complex semiotic structure, as a result of which it is often mixed with other linguistic phenomena that perform similar functions.

The semiotic value of the subject denotative is based primarily on a denotata, a direct and undivided representation of the object, which has text support in the form of a coreferential chain of various duration. Such a chain (phrasal and superphrasal) strengthens the referential base of the subject, which has the following characteristic properties:

1) obligation, which is that the non-subject is not part of the main core of a sentence, so it can often be omitted from the sentence, and the resulting sentence continues to be complete, which is impossible if the subject is omitted:

La de M. Teyssèdre arriva, (scandalisée, du fond de l’espace cotonneux).

La voix de M. Teyssèdre arriva, (scandalisée, du fond de l’espace cotonneux).

The voice of Mr. Teyssèdre arrived, (outraged, from the bottom of the cotton space) (En.).

Die Stimme von Herrn Teyssèdre kommt, (skandalös, aus dem Grund des Baumwollraums) (Ger).

Llegó la voz de Teyssèdre, (indignada, desde el fondo del espacio del algodón) (Sp.).

La voce di Teyssèdre è arrivata, (indignata, dal fondo dello spazio di cotone) (It.).

A voz de Teyssèdre chegou, (indignado, do fundo do espaço do algodão) (Port.).

The first, singular given part of this sentence may well reflect the completed real situation, which cannot be said of the autonomy of the bracketed part and its nominal components. Even the transfer of the predicate to the initial position in Russian and Spanish did not affect the information independence of the subject (Garipov et al., 2020) without the part of the sentence enclosed in brackets.

2) autonomy of the subject reference, which is possible as a result of the fact that the subject of speech must be determined (Garipov, 2016) for the listener (reader) at the time of pronunciation, so its identification does not depend on which (co)referent will be in the subsequent name group in this or a neighboring sentence; in this regard, if the two name groups in the narrative sentence are connected by a common reference, it is the non-subject that is placed (and sometimes omitted (see above)) in the right name position.

3) subjects may affect the processes of coreferential omissions and pronominalization of denotative nominative units, the autonomous nature of the reference of which explains the cases of loss of the coreferential pronoun subject, which is unacceptable without the distortion of meaning for dependent nominative units, for example:

P1: Un qui dort tient en cercle autour de lui le fil des heures, l’ordre des années et des mondes (Fr.).

A sleeping man keeps in a circle around him the hours, the order of years and worlds (En.).

Ein Mann, der im Kreis um ihn hält den Faden der Stunden, der Reihenfolge der Jahre und Welten (Ger.).

Un hombre dormido mantiene en círculo a su alrededor las horas, el orden de los años y los mundos (Sp.).

Un uomo addormentato tiene in cerchio intorno a sé le ore, l'ordine degli anni e dei mondi (It.).

Um homem dormindo mantém em um círculo em torno dele as horas, a ordem de anos e mundos (Port.).

P2: les consulte d’instinct en s’éveillant et y lit en une seconde le point de la terre qu’il occupe (Fr.).

He instinctively consults them by awakening and reads in one second the point of the earth he occupies (En.).

Instintivamente los consulta despertando y lee en un segundo el punto de la tierra que ocupa (Sp.).

Egli li consulta istintivamente svegliandosi e legge in un secondo il punto della terra che occupa (It.).

Ele instintivamente os consulta por despertar e lê em um segundo o ponto da terra que ele ocupa (Port.).

The locational subject in P2 is connected by a reliable coreferential bond with its support – the nominative subject (denotative) of the previous sentence, as a result of which turns into an optional element of this sentence: this is firstly proved by the fact that it can be completely eliminated using, for example, passive transformation (cf..) or replacing this pronoun with an indefinitely personal pronoun, and this will be quite justified, since the content of the juxtaposed sentence P1 approaches its content to the philosophical center in general and its subject is used with an indefinite article in the generalizing meaning in particular; secondly, the non-necessity of repeating a previously explicit subject is confirmed by its absence in the second part of the sentence P2. With regard to substitutes for non-subjective members of a sentence (uncoordinated attributes), they are obligatory to maintain the structural and, above all, semantic integrity of this context, on which, in particular, the possibility of determining the author is based (Jafariakinabad & Hua, 2022). These comments relate to both Germanic and Romanic languages.

4) subjects may to enter into coreferency relations across the boundary of the subordinate and principal clauses rather than any other name groups:

P1ne savait pas ce qu’ilpouvait promettre, et commençait à croire qu’elle voulait l’affiner pourtirer quelque argent.

P2: Mais le vent qui soufflait dans les arbres et le tonnerre qui commençait à gronderi mettait dans le sang comme une fièvre de peur.

P3: Ce n’est pas qu’craignait l’orage, mais, de fait, cet orage-lа était venu tout d’un coup et d’une manière qui neparaissait pas naturelle.

P4: Possible est que, dans son tourment,ne l’eūt pas vu monter derrière les arbres de la rivière.

P5: Mais, en fait,ne s’était avisé de l’orage qu’au momentlapetite Fadette leannocé (Sand 1978).

The relative element of the subjectin the subordinate clause is the pronoun, although in principle it is possible to admit the presence of a coreferential connection of the adverbial pronoun with the subject of the principal clause, because in modern French, unlike, say, Russian, the (dative) forms of male and female pronouns are not formally differentiated, i.e. there is an asymmetry in its sign structure (the same pronoun form correlates with different referents, which may lead to ambiguity in the process of advancing the text in the case of weakening the structure of the first nominative group (here the term “nominative” covers not only nouns possessing a nominative, naming function, but also pronouns with an inherent relative reference, i.e. this term is used synonymously with the word of the name chain):

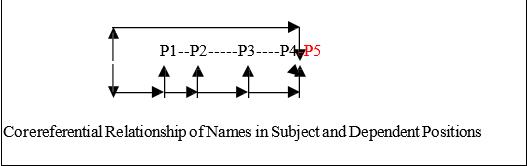

P1:Landry-il-(lui)-il-(elle)-le-lui-P2:lui-P3:il-lui-P4:son-Landry-P5:il-se-(la Fadette)-lui.

The chain sequence of two parallel name chains shows that the first name chain () differs from the second (taken in brackets) both qualitatively, since most of its members are in the dominant position, and quantitatively – the number of members of the first chain (13) significantly exceeds the number of members of the second (4).

However, the reader, even if he does not know the content of the previous text, on the basis of his language competence (Jung, 2001) will easily correlate the subject of with the anaphor, because such a “bridging” between the main and subordinate sentences is consistent with the norms of the French language.

Besides, the correctness of the choice is evidenced, in particular, by the appearance of the coreferential pronoun in the position of a subject in the second part of a complex sentence P1 and in subsequent sentences.

With regard to the subject of the subordinate clause, it can be observed to be inconsistent with the subject antecedent (–), which leads to a change in the categorical (syntactic) status of the main and dependent members of this subordinate clause, i.e. the former dependent pronoun of the parallel name chain begins to function as a subject, and the subject of the principal clause acts as an object. But the dominant role of the first stronger and longer nominative chain is restored in subsequent sentences (Figure 1).

There may be a question on the coreferency to a name with a distracted meaning. It seems that in this case it is necessary to answer in the affirmative, because even the names of objects that do not exist in reality are a generalized reflection of the phenomena that are somehow represented in the consciousness (Knaak et al., 2021) of the members of this language group:

P1: Vous êtes donc? dit don Cléophas un peu troublé de la nouveauté de l’aventure (So you are the? says Don Cleophas a little worried about the novelty of adventure).

P2:suisé, repartit la voix: (, there was a voice);

(You came here very much to the point to get out of slavery).

P4:languis dans l’oisiveté, carsuisde l’enfer le plus vif et le plus laborieux. (Lesage 1973). ( fade from idleness, because am the most lively and hardworking of hell).

The subject of speech of this superphrasal unity is believed to be a nonexistent referent (), however this null referent cannot be considered as absolutely nonexistent since throughout long history the learning human consciousness reflected the most general exaggerations which reached supernatural heights, the negative lines of the person which, apparently, can be applicable to separate quite real languages of the representatives of the human race.

Therefore, given this drawback, when constructing a linguistic model in another branch of machine translation (Lee & Baylor, 2006) – engineering linguistics – not only semantic, but also communicative-pragmatic properties of the language sign are taken into account.

In particular, for a comprehensive study of the nature of the subject of the statement, a frame of cognitive and communicative human activity is used (Miklayera, 2011) in the form of structures with blank and filled structures, or slots where the filled slot occupies a bundle, and the nominal (unpopulated) slots act as thematic (T) and rheumatic (R) positions and receive lexical filling based on real bid data obtained from the use of the methods of automatic analysis.

In this regard, the language model as a means of information storage and transmission allows seeing how the language mechanism functions when generating a message, namely if the name class corresponds to the class of objects known to the native speaker, and the class of predicates as properties of these objects is also within the language competence of the medium, then this connection of the predicate with the name contains something already known to the listener from knowledge of the language and reality; only the way speakers choose exactly these combination components will be new for him along with encyclopedic information about the surrounding world (Nahavandi & Mukundan, 2013).

In other words, names and predicates in expressions, and in particular statements, are replaced only when the same relation of names to objects and predicates to properties is preserved, and the combination of the name with the predicate and its result is a predication, which in natural (informal) language represents only the first stage of the predicative process; the second stage consists in affirming or denying the predication regarding validity (in its truth or falsity), which can be objectively determined based on the use of artificial languages, in particular, the Python programming language (Seitz & Arnold, 2021).

Thus, a sentence as a communicative unit is a structure consisting of two parts, which are connected to each other by a predicative relation. In predication, the component that has the greatest meaning of objectivity is called a subject, and the other part is an object.

So, despite their formal logical binomiality, a semantic difference in structure is found in the sentences(a child cries),(a bridge is destroyed), (a wife is making breakfast), (it is snowing). In the sentence the subject denotes not only the logical subject, but also the actor (agent); in the sentencethe subject means a logical object that is not an actor: it is an object, or a passive person (patient). The sentenceis a two-member sentence only formally; in fact, we have a semantically non-separable construct, and only in the first sentence the logical subject and predicate coincide with the grammatical subject and the spoken one, respectively, i.e. it is difficult to attribute it to the independent members of a sentence and, as a result, such sentences are often considered to be one-member sentences.

Conclusion

Thus, we can replace names and predicates in expressions, and in particular statements, only by preserving the same relation of names to objects and predicates to properties, and the combination of a name with a predicate and its result is a predication, or proposition, which in a natural (informal) language is only the first stage of the predicative process; the second stage consists in approving or denying a predication of validity (in its truth or falsity) in an artificial or formalized programming language.

References

Garipov, R. K. (2016). Peculiarities of categorization processes in diverse languages. Bulletin of Bashkir University, 21(4), 739–743. https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=27260818

Garipov, R. K., Khusnutdinova, F. A., & Tsypina, A. R. (2020). Influence of context on the semantics of connecting nouns in English. Bulletin of Bashkir University, 25(4), 944–947. https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=44648832

Jafariakinabad, F., & Hua, K. A. (2022). A self-supervised representation learning of sentence structure for authorship attribution. ACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data (TKDD), 16(4), 1–16. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2010.06786.pdf

Jung, I. (2001). Building a theoretical framework of webǦbased instruction in the context of distance education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 32(5), 525–534.

Knaak, T., Grünke, M., & Barwasser, A. (2021). Enhancing Vocabulary Recognition in English Foreign Language Learners with and without Learning Disabilities: Effects of a Multi Component Storytelling Intervention Approach. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 19(1), 69–85.

Lee, M., & Baylor, A. L. (2006). Designing metacognitive maps for web-based learning. Educational Technology & Society, 9(1), 344–348.

Miklayera, L. (2011). Discursive Choices in a Formalized Setting of Diplomatic Communications. International Journal of Communication, 21(2), 5–26.

Nahavandi, N., & Mukundan, J. (2013). Iranian EFL Engineering Students’ Motivational Orientations towards English Language Learning along Gender and Further Education. Language Institutes. International Journal of Linguistics, 5(1), 72.

Seitz, J., & Arnold, T. (2021). Black Hat Python: Python Programming for Hackers and Pentesters. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?start=60&q=Grabe,+W.++Research+on+teaching+reading.+Annual+Review+of+Applied+Linguistics,+24,+44-69.&hl=ru&as_sdt=0,5&as_ylo=2021

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

23 December 2022

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-128-7

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

129

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1335

Subjects

Science, philosophy, academic community, scientific progress, education, methodology of science, academic communication

Cite this article as:

Garipov, R. K., Khusnutdinova, F. A., Tsypina, A. R., Iksanova, R. M., & Gumerova, N. Z. (2022). Logical-Semantic And Referential Properties Of A Subject. In D. K. Bataev, S. A. Gapurov, A. D. Osmaev, V. K. Akaev, L. M. Idigova, M. R. Ovhadov, A. R. Salgiriev, & M. M. Betilmerzaeva (Eds.), Knowledge, Man and Civilization- ISCKMC 2022, vol 129. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 473-479). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2022.12.59