Transcending Pandemics: Conceptualising the Centrality of Communication in Fostering Community Resilience

Abstract

The global impact of COVID-19 has been devastating. The grim mantra of new norm repeated the world over indicates that COVID-19, unlike previous disasters, negates the possibility of bouncing back. As such, we need to rethink how we conceptualize community resilience, moving away from the nostalgic ideas of bounce back, and embracing the notion of bounce forward. Indeed, humans have bounced back from seven coronaviruses in the likes of common colds, and the SARS and MERS pandemics. The COVID-19 pandemic, however, spreads much faster than past pandemics and brings paradigmatic changes with widespread effects pervading various facets of life, from the social to the economic aspects. Past preparations had mainly focused on stopping transmission and largely neglected the socio-economics repercussions. In this paper, communication is proposed to play a central role in fostering community resilience in the bounce-forward notion in pandemics. The roles of communication in the long-term stability and viability of communities, in the bounce-forward notion, has been understudied. In addition to disseminating information and creating awareness, communication can also act as a vital enabler to break down silos, share knowledge, ensure equitable access, and foster vertical and horizontal, top-down and bottom-up working relationships. More needs to be explained on the centrality of communication in capacity building, adaptation to new realities and seizing opportunities that the current media and communication landscapes have to offer. Pandemics will be our new normal, thus, we need to gear up, to avoid the ‘coronacoma’ that we are experiencing with COVID-19.

Keywords: Capacity building, communication, community resilience, COVID-19, pandemic

Introduction

Unlike past pandemics, COVID-19 spreads much faster and brings paradigmatic changes and compounding effects on communities from the social, cultural, political and economic aspects. Existing community resilience frameworks based on bounce-back principles that focus on going back to normality are inadequate when communities are expected to embrace the new normal, deal with changes from disruptions and embrace new realities. Therefore, community resilience needs to be reconceptualised into bounce-forward community resilience thinking that recognises complex adaptive system dynamics, enabling communities to continuously adapt new development pathways during pandemics. In this paper, a conceptual framework is presented to explain the centrality of communication in fostering community resilience in the bounce-forward notion in pandemics. The roles of communication in the long-term stability and viability of communities, in the bounce-forward notion, has been understudied. In addition to disseminating information and creating awareness, communication can also act as a vital enabler to break down silos, share knowledge, ensure equitable access, and foster vertical and horizontal, top-down and bottom-up working relationships. Therefore, more efforts have to be placed in explaining how communication may contribute to capacity building, adaptation to new realities.

Problem Statement

Indeed, the human civilization have in the past bounced back from various pandemics. The coronaviruses are not new with seven already identified to be infectious to human. We are living and continuously adapting to coronaviruses HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-HKU1, which causes the common cold (Signer et al., 2020). We have endured through two pandemics related to coronaviruses, with SARs-CoV identified in 2002 as the cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and MERS-CoV identified in 2012 as the cause of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) (Paules et al., 2020). COVID-19 associated with the SARS-CoV-2, presents similar symptoms but spreads much faster than SARS and MERS (Peeri et al., 2020), and with much broader depth of impact on society, affecting psychological, social, cultural, economic, and political spheres. Calls to brace for the onset of such widespread pandemic have been heard in the past. In expectation of impending pandemics, many countries around the world such as South Korea the United States have taken various pre-emptive measures such as increasing stockpiles of personal protective equipment and establishing a dedicated unit for pandemic disaster management. However, much of the preparation was about putting a stop to the disease per se, but much less on mitigating the extended and compounded socio-economic impacts that hinder communities from moving forward.

Arguably, past community resilience frameworks in the context of pandemics management have overemphasised on immediate response and swift recovery from the outbreak. In the abovementioned experiences with SARS and MERS, a community is considered resilient in so much that it was able to fend the disease and get back to business as usual. Emphasis was placed on risk and health communication to create awareness and prepare the public on knowing what to do in response to a disease outbreak in the immediate term. However, COVID-19 brought paradigmatic changes that left us unprepared for its widespread and long-term effects. We are left grappling in embracing the new norms pervading various facets of life, from the way we socialise, work, learn, do business, get medical treatment and even how we practice religion.

Unfortunately, our past experiences with past pandemics have given us a myopic view and short- term vision on community resilience. Mechler et al. (2020) explained that unlike past pandemics, COVID-19 is a manifestation of compound, systemic and existential risk that in turn leads to a compounding of impact that breach coping capacities of communities or even national governments. For instance, Malaysia is suddenly thrust into online education, affecting almost 5 million school students and 1.2 million university students (Abdullah et al., 2020). Nevertheless, adopting to massive virtual education had not been in the past equation and as such leave pockets of communities in a lurch. COVID-19 forces us to reimagine the future, to embark upon brave paradigmatic changes, and to scour unchartered territories to build a more conducive and prosperous ecosphere. Moreover, COVID-19 has pulled back the veil on longstanding issues of social inequity and injustice, often striking down the most vulnerable in our society. A new framework based upon resilience would necessarily include notions of prosperity, equality, and social justice. Therefore, community resilience needs to be contextualised in wider perspectives.

Communication is postulated to play a key role in the effort to foster community resilience. Communication is not only about disseminating information, but also acts as a vital enabler to break down silos, share knowledge, ensure equitable access (e.g. information, health and economic stimulus), and foster vertical and horizontal, top-down and bottom-up working relationships. Much research in disaster communication globally, are understandably focused on the immediate needs of the emergency at hand, particularly in extending timely and effective responses from humanitarian and relief aspects (Chacko et al., 2018). However, the role of communication in the long-term stability and viability of communities and townships, in the bounce-forward notion, has been understudied. More needs to be explained on the role of communication in capacity building, adaptation to new realities and seizing opportunities that the current media and communication landscapes have to offer.

To be sure, the National Disaster Management Agency [NADMA] (2019) in its strategic plan, Pelan Strategik Agensi Pengurusan Bencana Negara 2019-2023, has identified community resilience, albeit in the bounce-back notion, as one of its key thrust areas, focusing on the economy, social, cultural values, education and awareness in post-disaster recovery and in facing future disasters. This research is hoped to facilitate in addressing NADMA’S effort in building community resilience from the bounce-forward perspective. The framework will contribute towards the nation’s preparation and future responses to disasters, allowing agencies and task forces, particularly National Disaster Management Agency (NADMA) and the National Security Council, to provide utmost modern and relevant services with holistic solutions through the most advanced tools and knowledge and guided by long-term visions. The integrated communication platform will also assist NADMA in coordinating more than 79 agencies that it has to work with at the federal, state and district levels.

In the bigger picture, research on this area will support Malaysia’s commitment to the Sustainable Development Goal 3 – Good Health and Wellbeing. It also contributes towards the country committing to the Hyogo Framework for Action and its three strategic goals: (1) the integration of disaster prevention, mitigation, preparedness, and vulnerability-reduction considerations into sustainable development policies, planning, and programs; (2) the strengthening of local capacities that build hazard resilience; and (3) the incorporation of risk reduction into emergency preparedness, response, recovery, and reconstruction programs in affected communities (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction [UNISDR], 2005).

Research Question

Two research questions are addressed in this paper.

- Firstly, what are the critical dimensions in conceptualising bounce forward community resilience in the context of pandemics?

- Secondly, how does communication play central roles in fostering bounce-forward community resilience in the context of pandemics?

Research Methods

In this paper, a critical review of the extant literature on community resilience and disaster communication was employed. The literature was analysed for key dimensions in conceptualising the bounce forward notion of resilience and identifying the key dimensions of communication during disaster management and the relevant strategic approaches. The dimensions were then included in an integrated conceptual framework.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study is to propose a conceptual framework that demonstrates the centrality of communication in fostering bounce forward community resilience during pandemics. The conceptual framework provides a new perspective in understanding community resilience, and the critical areas in communication that needs to be addressed for community resilience during pandemics.

Findings

Resilience has been broadly defined as the capacity of systems such as communities and the environment to recover from a disruption such as natural disasters (Folke, 2016). Most definitions emphasise on the ability to persist during adversity and return to the equilibrium afterwards (Folke, 2016; Paton (2006); Pfefferbaum et al., 2015a). Subsequently, the study of resilience developed into an approach to understand the capacity and ways people, communities, societies, and cultures navigate adversity to generate positive outcomes (Folke, 2016). Following this definition, resilient communities in general are communities that are able to face disruptions successfully and adapt to the changes brought by the adversity. For some communities, not only were they able return to the equilibrium but thrived and transformed into a better position (Folke, 2016). Therefore, adversities can open opportunities for new ideas and new ways of living (Chacko et al., 2018; Davoudi et al., 2012; Folke, 2016; Manyena et al., 2011).

Community Resilience

The wake of COVID-19 saw much of the research effort centered on understanding resilience through individual resilience rather than community resilience. As Ungar (2011) has observed, personal resilience of individuals is inextricably linked to the resilience of their community, and that “most individuals are only as successful as their communities as a whole,” and that “individual success depends on” the community’s resources (p. 1742). Ungar (2011) recognizes that “the community’s social and physical ecology are more important to the resilience of its members” than the characteristics of individual members alone (p. 1744). Our experience with COVID-19 has taught us that pandemics upends communities and the systems within. The idea of social or physical distancing underscores the importance of a whole systems approach – individuals and groups are intricately connected, with each participant having a role to play and whose actions affects the system as a whole (South et al., 2020).

Although the onset of COVID-19 has seen the escalation of studies on resilience, apart from few exceptions (Bento & Couto, 2021; Kimhi et al., 2020; Mechler et al., 2020; Ratuva et al., 2020) much of these efforts have been focused on individual resilience typically from the mental health and psychological perspectives, as opposed to community resilience. Studies of resilience in the context of the COVID-19 in Malaysia lean towards analyses at the individual and national responses or impacts. For example, at the individual level, Yau et al. (2020) explored behavioural changes in response to the COVID-19 pandemic; Wong and Alias (2020) examined psycho-behavioural responses in the early phases of COVID-19; and Rohayah et al. (2020) investigated the resilience of senior citizens during pandemics. At the national level, the focus has been on government responses in mitigating health and economic impacts. For example, Shah et al. (2020) accounted the government responses in mitigating COVID-19 outbreak and in addressing the consequent economic downturn. Abdullah et al. (2020) delineated Malaysia’s unique responses to the pandemic. These streams of research have yet to fully address resilience at the community level from the bounce-forward perspective.

In our review of past literature, three perspectives emerged as meaningful and relevant to our proposed study. Paton (2006) conceptualised community resilience based on three key aspects of disruptions: physical, social and behavioural. In their conceptualisation, the physical aspect refers to loss in the physical integrity of the built environment and include concerns on building codes, land use and planning, and the capacity of buildings and environment to withstand disaster; the social aspect refers to issues of equitable distributions of costs and benefits to a community; and the behavioural aspect refers to courses of actions that are undertaken to mitigate, respond and adapt to disasters. Berkes and Ross (2013) observed that community resilience may also be conceptualised based on two levels of resilience: the socio-ecological level and the psychological level. The socio-ecological level views resilience from the macro, community ecosystem, and the psychological level deals with the micro, individual aspects of resilience. On the other hand, Pfefferbaum et al. (2015b) considered three representations of resilience: properties, processes and outcomes. Properties of resilience refer to the objects that are subjected to disruptions including individuals and communities; processes related to the set of activities over time in addressing disruptions, which resulted in the outcome such as the reactions to, or consequences of, the activities and behaviours. In our proposed study these perspectives will be examined and critically assessed in identifying the barriers, challenges and opportunities in fostering bounce-forward community resilience.

Manyena et al. (2011) argued that the “bounce-back” notion of resilience denote a return to vulnerability (i.e. the original state) and does not recognise that disaster events inevitably brings change to the community. On the other hand, communities must deal with various changes because of the disruptions, thus a return to the original state is unlikely. Similarly, Folke (2016) in his arguments for resilience thinking explained that resilience in some fields is viewed in a narrow sense with an implicit focus on trying to resist change and control it to maintain stability. He promotes the adaptation of resilience thinking that recognises complex adaptive system dynamics and that people, communities, societies, and cultures adapt or even transform into new development pathways in the face of dynamic change. To him, resilience is about persisting with change on the current path of development and adapting, improving, and innovating on that path. In these alternative views, resilience is framed as a more optimistic and progressive new reality.

As an alternative and in tandem with resilience thinking Manyena et al. (2011) proposed a “bounce-forward” notion of resilience. They conceptualise resilience as “the intrinsic capacity of a system, community or society predisposed to a shock or stress to “bounce forward” and adapt in order to survive by changing its non-essential attributes and rebuilding itself” (p. 3). The bounce-forward notion of resilience signals moving forward with the new realities and utilising available resources to create new trajectories and looking up for opportunities to improve. They emphasised that this new notion has implications on how we do research as it revisits the philosophy and arguments surrounding disaster, risk and community resilience. It also has implications for on-the-ground planning as the new notion broadens the horizon to a more long-term planning. Additionally, it has psychological implications as it is inherently optimistic and will assist in encouraging victims and service providers to adopt positive behaviour changes in relation to the disaster.

In this paper, the bounce-forward notion will be adapted in our conceptualisation of resilience. It is also proposed that the bounce-forward notion should be embraced at the national level in managing other recurring disasters. A bounce-forward approach in managing disasters will bring into view the changes that have taken place (i.e. the 'new normal' that comes with disasters beyond pandemics) and the changes that needs to be addressed in future plans.

Communication, Pandemics and Community Resilience

The crucial role of communication in building community resilience has often been raised in past literature. Houston et al. (2015) recognised communication, in some form, is a central component of most if not all community resilience models. In arguing for the centrality of media and communication in community resilience, Houston et al. (2015) identified three areas of communication that can be integrated into resilience frameworks, namely communication ecology, public relations and strategic communication. In addition, Rice and Jahn (2020) has proposed communicative practices as key resources in learning lessons from past disasters in preparation for future disasters. Ataguba and Ataguba (2020) propound that effective crisis and risk communication are crucial in building trust, credibility, honesty, transparency, and accountability in ensuring health equalities in developing countries.

Much advancement has been made on leveraging communication in response and recovery efforts during disaster events (Reams et al., 2017; Rollason et al., 2018; Stephenson et al., 2018; Yahya et al., 2004). To be sure, the current COVID-19 crisis and past pandemics have seen numerous studies of communication frameworks in the context of pandemics management. However, much of these works are focused on risk, crisis and emergency communication (Abrams & Greenhawt, 2020; Finset et al., 2020; Jong, 2021; Yu et al., 2020). With the exception of a few (Burnside-Lawry et al., 2013; Che Hamid et al., 2019; Houston, 2018; Zakaria et al., 2014), much less attention has been placed on the role of communication in capacity building and adaptation to new realities for pandemic afflicted communities.

Communication scholars have theorized resilience as a continuous process in which deliberate communicative choices facilitate adaptability to a new normal (Buzzanell, 2010). Ravichandran et al. (2018) explain that communication is an important aspect in the event of disaster as well as in the aftermath as part of the response and recovery initiatives. The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research (2013) contends that credible and accessible communication are crucial in community’s resilience. Moreover, Norris et al. (2008) has identified information and communication technology as one of the crucial adaptive capacities in building community resilience.

Communication is relevant in all four phases of disaster cycle: preparation (i.e. warning), response (i.e. event is here), recovery and mitigation (i.e. quiet time) (Wald, 2013). Communication helps in coordinating the right resources and messages among different stakeholders. Particularly, there are two stakeholders that are considered important during a disaster cycle: the upstream (i.e. agencies) and downstream (i.e. individuals or communities) in advocating and improving resilience in the stages of disaster (Martin et al., 2016). Downstream stakeholders here are the populations or community that are affected by the disaster, whereas the upstream are the agencies that oversee the resources, media and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and non-government individuals (NGIs). Understanding the demands of both upstream and downstream groups is imperative in enhancing the resilience of the community. Effective integration of communication strategies will be able to influence behaviours of both stakeholders and resource organisations across all stages of disaster cycle to mitigate future risks and support community resilience (Martin et al., 2016). Communication also comes into play in handling crisis, as well as in pooling resources of various organisations, agencies or partners. In integrating communication in the disaster cycle, a dynamic strategy management is needed to integrate resources during the mitigation process. Among those that conduct the resources integration are senior managers, middle-ranking managers and low-level managers.

One of the key principles in disaster management is that all relevant units (e.g. different agencies and organisations involved in disaster and risk management) moves away from working in silos. The focus should be placed on a long-term communication process, targeting towards a wide range of stakeholders including local community, local councils, and regulators. Its implementation mainly involves cross-functional organizational teams and departments such as federal agencies, state agencies, NGOs and NGIs in achieving a common vision (e.g. community resilience). Such approach is aligned with the “whole system” approach in community-centred public health that recognises the importance of stakeholders working in solidarity and partnership to create conditions that allow communities to thrive post-pandemic (South et al., 2020).

In understanding the relationships and networking among actors, this research will turn to social network analysis. Jones and Faas (2017) explains that before, during, and after a disaster, people, agencies, and organizations both help and hinder each other, alternatively opening up new possibilities and hamstringing others. He highlighted that in many ways, exposures to hazards become disasters in large part as a result of relational patterns in societies, and our responses to disasters. Likewise, emergency deployment, mitigation, coping, and adaptation are facilitated and obstructed by variations in coordination and support between networks of actors.

In their review, Chacko et al. (2018) established that coordinating a network of diverse and geographically separated actors (Balcik et al., 2010; Comfort, 2007; Dubey & Altay, 2018) in disaster operations management in disasters is challenging given that these diverse actors may have dissimilar, and possibly conflicting, goals, depending on their roles in the process (Balcik et al., 2010; Chacko, 2015). They argue that given this complexity, it is critical for researchers to continue developing decision support systems that can lead to more timely and effective decision making. They also note that much of the literature is generally motivated by planning for a specific disaster event (Chacko et al., 2014; Chacko et al., 2016; Overstreet et al., 2011), and discussions on goals have typically focused on addressing immediate needs of a current emergency or a disaster at hand. They argued that such approaches miss out on the opportunity to consider information about long-term community stability and viability (Bealt & Mansouri, 2018; Habsburg-Lothringen, 2015).

The Outside-In or Customer/Audience-centric perspective in communication emphasizes on deep understanding on the needs and wants of the audiences (Bruhn & Schnebelen, 2017, p. 471). In the context of pandemics, the Outside-In approach entails “listening and learning” as well as sharing resources including data and facilities, to continuously move forward in building community resilience. Although it is acknowledged that there is currently strong working relationship among the actors involved in pandemic disaster management at the national level, more needs to be achieved in terms of the sharing of data, knowledge and expertise, and in establishing on-going dialogue towards long term visions at the community level.

Conceptual Framework

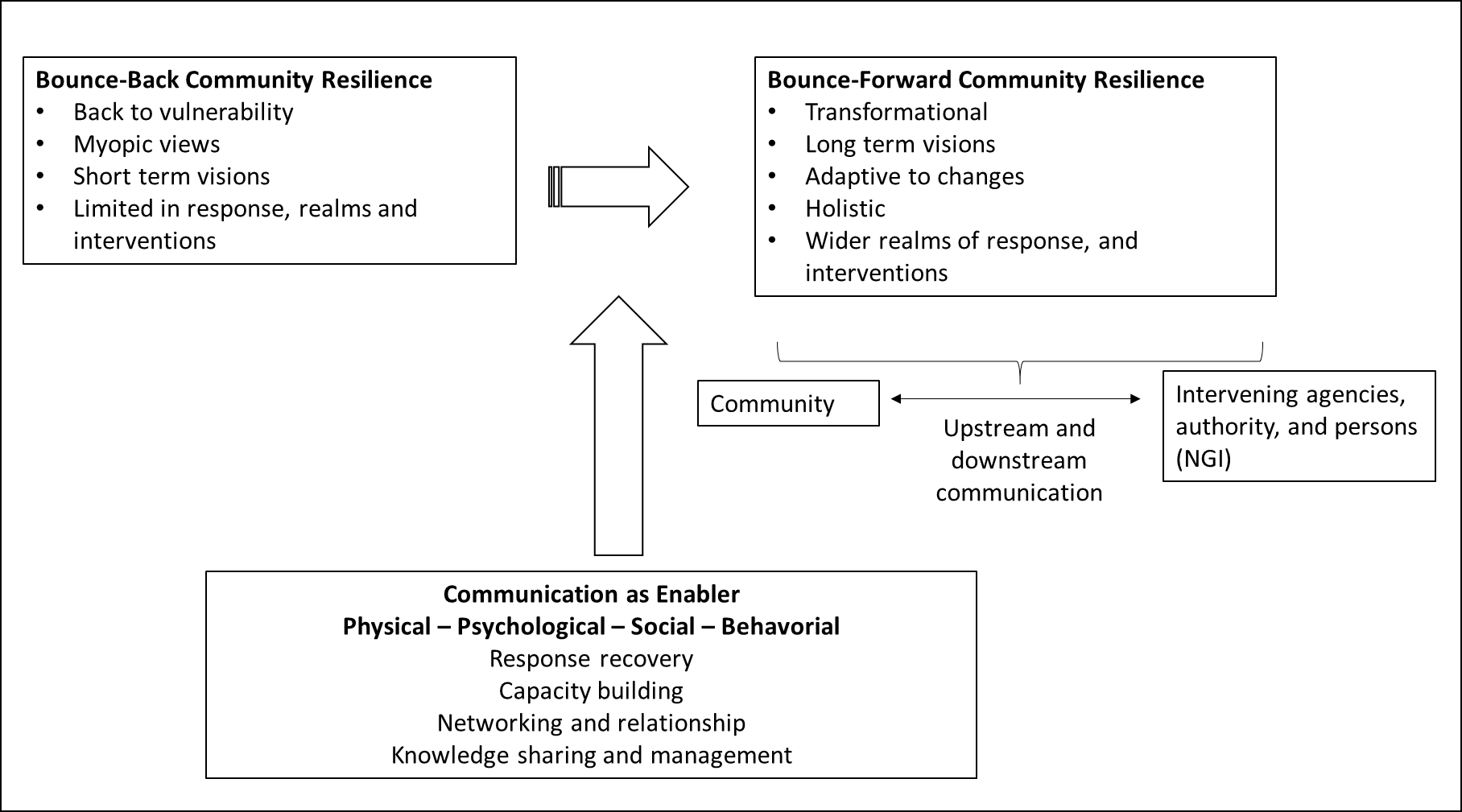

We argue for the reconceptualization of community resilience during pandemics based on the above discussed bounce-forward notions. We propose that the conceptualisation of community resilience need to move away from the expectations of going back to the original state, meaning going back to the state of vulnerability as explained in the past literature. The conceptual framework is presented in Figure 1.

In our framework, communication should be used as an enabler to move the community from the state of vulnerability (bounce-back resilience) to transformational and adaptive changes (bounce-forward resilience). Rather than having a myopic view and being short sighted on what community resilience constitute, we need to extend our conceptualisation to include transformational changes and long-term visions. Communication should be used to equip the communities with skills (e.g. through capacity building workshops) so that they will be more adaptive to changes when stricken with pandemic. Moreover, communication should not just be utilised in addressing the immediate issue (e.g. spreading awareness/knowledge about mitigating spread of pandemic), but should include putting in place measures that will cover macro dimensions including social, cultural and economic consequences. We have learnt from the COVID-19 experience that the realms of response and intervention need to be wide, far-reaching, and multidimensional.

In our framework, communication is proposed to play a central in fostering bounce forward community resilience. It is proposed that in coordinating efforts towards fostering community resilience, four aspects of resilience namely psychological, social, behavioural and physical aspects, need to be addressed in a holistic disaster management communication framework, with communication becoming the enabler not only in disseminating information, but also in breaking down silos, sharing of knowledge, ensuring equitable access (e.g. information, health and economic stimulus), and fostering vertical and horizontal, top-down and bottom up working relationships.

To the abovementioned ends, the upstream and downstream communication is critical – the community and the intervening entities (e.g. government agencies, NGOs and NGIs) should be continuously be in communication, providing feedback to each other, and working together as opposed to ‘for the other’. It is argued that the upstream and downstream communication will address among others, the issues of inadequate or wrong allocation of resources, misunderstandings, misconceptions, and mistrusts.

Conclusion

The conceptualisation presented in this paper is hoped to contribute towards enhancing national policies related to disaster and risk management, specifically on pandemic as a national disaster. The policies that are of consequent include those pertaining to the National Security Council Act and the 12th Malaysia Plan. To some extent, this research is also relevant to the National Community Policy (Dasar Komuniti Negara) in envisioning a more resilient community living in challenging environments.

Communities afflicted with pandemics will gain better quality of life and standard of living through new ideas and approaches arising from a holistic integrated communication framework. They will be able to focus more on social and economic development and move forward with new ideas and opportunities emerging from synergistic efforts of all stakeholders, and mutually leveraging on each others' expertise and resources (e.g. artificial intelligence, machine learning and GIS technology). The integrated communication framework will also ensure that all parties could work cohesively and responsibly, putting aside political differences towards a common cause of fostering community resilience. Additionally, the findings from this research will be shared with the public through the national mainstream media.

References

Abdullah, J. M., Ismail, W. F. N. M. W., Mohamad, I., Ab Razak, A., Harun, A., Musa, K. I., & Lee, Y. Y. (2020). A critical appraisal of COVID-19 in Malaysia and beyond. The Malaysian journal of medical sciences: MJMS, 27(2), 1.

Abrams, E. M., & Greenhawt, M. (2020). Risk communication during COVID-19. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, 8(6), 1791-1794.

Ataguba, O. A., & Ataguba, J. E. (2020). Social determinants of health: the role of effective communication in the COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries. Global health action, 13(1), 1788263.

Balcik, B., Beamon, B. M., Krejci, C. C., Muramatsu, K. M., & Ramirez, M. (2010). Coordination in humanitarian relief chains: Practices, challenges and opportunities. International Journal of production economics, 126(1), 22-34.

Bealt, J., & Mansouri, S. A. (2018). From disaster to development: a systematic review of community‐driven humanitarian logistics. Disasters, 42(1), 124-148.

Bento, F., & Couto, K. C. (2021). A Behavioral Perspective on Community Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Paraisópolis in São Paulo, Brazil. Sustainability, 13(3), 1447.

Berkes, F., & Ross, H. (2013). Community resilience: toward an integrated approach. Society & Natural Resources, 26(1), 5-20.

Bruhn, M., & Schnebelen, S. (2017). Integrated marketing communication – from an instrumental to

customer-centric perspective. European Journal of Marketing, 51(3), 464-489.

Burnside-Lawry, J., Akama, Y., & Rogers, P. (2013). Communication research needs for building societal disaster resilience. The Australian Journal of Emergency Management,28(4), 29.

Buzzanell, P. M. (2010). Resilience: Talking, resisting, and imagining new normalcies into being. Journal of Communication, 60(1), 1-14.

Chacko, J. (2015). Sustainability in Disaster Operations Management and Planning: An Operations Management Perspective. Virginia Polytechnic and State University. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/71759/Chacko_J_D_2015.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed =y

Chacko, J., Rees, L. P., & Zobel, C. W. (2014). Improving Resource Allocation for Disaster Operations Management in a Multi-Hazard Context. Proceedings of the 11th International ISCRAM Conference, 83-87.

Chacko, J., Rees, L. P., Zobel, C. W., Rakes, T. R., Russell, R. S., & Ragsdale, C. T. (2016). Decision support for long-range, community-based planning to mitigate against and recover from potential multiple disasters. Decision Support Systems, 87, 13-25.

Chacko, J., Zobel, C. W., & Rees, L. P. (2018). Challenges of Modeling Community-Driven Disaster Operations Management in Disaster Recurrent Areas: The Example of Portsmouth, Virginia. ISCRAM.

Comfort, L. K. (2007). Crisis management in hindsight: cognition, communication, coordination, and control. Public Administration Review, 67(S1), 189–197.

Davoudi, S., Shaw, K., Haider, L. J., Quinlan, A. E., Peterson, G. D., Wilkinson, C., Fünfgeld, H., McEvoy, D., Porter, L., & Davoudi, S. (2012). Resilience: a bridging concept or a dead end? “Reframing” resilience: challenges for planning theory and practice interacting traps: resilience assessment of a pasture management system in Northern Afghanistan urban resilience: what does it mean in planning practice? Resilience as a useful concept for climate change adaptation? The politics of resilience for planning: a cautionary note: edited by Simin Davoudi and Libby Porter. Planning theory & practice, 13(2), 299-333.

Dubey, R., & Altay, N. (2018). Drivers of Coordination in Humanitarian Relief Supply Chains. In The Palgrave Handbook of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management (pp. 297-325). Palgrave Macmillan.

Finset, A., Bosworth, H., Butow, P., Gulbrandsen, P., Hulsman, R. L., Pieterse, A. H., Street, R., Tschoetschel, R., & van Weert, J. (2020). Effective health communication–a key factor in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. Patient Education And Counseling, 103(5), 873.

Folke, C. (2016). Resilience (republished). Ecology and Society, 21(4).

Habsburg-Lothringen, F. (2015). When peace is pieces and war is wonderful: an examination of narratives around violence, power and humanitarian aid: a case study of south Sudan [Doctoral Dissertation]. Fordham University. http://fordham.bepress.com/dissertations/AAI1600838/ Last accessed October 2017

Hamid, H. E. C. M., Saad, N. J. A., Razali, N. A. M., Khairuddin, M. A., Ismail, M. N., Ramli, S., Muslihah, W., Ishak, K. K., Ishak, Z., Hasbullah, N. A., Wahab, N., Zainudin, N. M., & Shah, P. N. N. A. (2019, November). Disaster Management Support Model for Malaysia. In International Visual Informatics Conference (pp. 570-581). Springer, Cham.

Houston, J. B. (2018). Community resilience and communication: dynamic interconnections between and among individuals, families, and organizations. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 46(1), 19-22.

Houston, J. B., Spialek, M. L., Cox, J., Greenwood, M. M., & First, J. (2015). The centrality of communication and media in fostering community resilience: A framework for assessment and intervention. American Behavioral Scientist, 59(2), 270-283.

Jones, E. C., & Faas, A. J. (2017). An introduction to social network analysis in disaster contexts. In Social network analysis of disaster response, recovery, and adaptation (pp. 3-9). Butterworth-Heinemann.

Jong, W. (2021). Evaluating Crisis Communication. A 30-item Checklist for Assessing Performance during COVID-19 and Other Pandemics. Journal of Health Communication, 1-9.

Kimhi, S., Marciano, H., Eshel, Y., & Adini, B. (2020). Recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic: Distress and resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 50, 101843.

Manyena, B., O'Brien, G., O'Keefe, P., & Rose, J. (2011). Disaster resilience: a bounce back or bounce forward ability? Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability, 16(5), 417-424.

Martin, I. M., Martin, W. E., Baker, S. M., Scammon, D. L., & Wiener, J. (2016). Disasters and social marketing. Persuasion and social marketing, 77-116.

Mechler, R., Stevance, A. S., Deubelli, T., Linnerooth-Bayer, J., Scolobig, A., Irshaid, J., Handmer, J., Hochrainer-Stigler, S., & Schinko, T. (2020). Bouncing Forward Sustainably: Pathways to a post-COVID World. Governance for Sustainability.

National Disaster Management Agency [NADMA]. (2019). Pelan Strategik Agensi Pengurusan Bencana Negara 2019-2023 [State Disaster Management Agency Strategic Plan 2019-2023]. http://www.nadma.gov.my/images/nadma/documents/pelanstrategik/PS_NADMA_2019-2023_v2.pdf

Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F., & Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American journal of community psychology, 41(1), 127-150.

Overstreet, R. E., Hall, D., Hanna, J. B., & Rainer, R. K. (2011). Research in humanitarian logistics. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management, 1(2), 114-131.

Paton, D. (2006). Disaster resilience: building capacity to co-exist with natural hazards and their consequences. Disaster resilience: An integrated approach, 3-10.

Paules, C. I., Marston, H. D., & Fauci, A. S. (2020). Coronavirus infections—more than just the common cold. Jama, 323(8), 707-708.

Peeri, N. C., Shrestha, N., Rahman, M. S., Zaki, R., Tan, Z., Bibi, S., Baghbanzadeh, A. N. M., Zhang, W., & Haque, U. (2020). The SARS, MERS and novel coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemics, the newest and biggest global health threats: what lessons have we learned? International journal of epidemiology, 49(3), 717-726.

Pfefferbaum, B., Van Horn, R. L., & Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2015a). A Conceptual Framework to Enhance Community Resilience Using Social Capital. Clinical Social Work Journal, 45(2), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-015-0556-z

Pfefferbaum, R. L., Pfefferbaum, B., Nitiéma, P., Houston, J. B., & Van Horn, R. L. (2015b). Assessing community resilience: An application of the expanded CART survey instrument with affiliated volunteer responders. American Behavioral Scientist, 59(2), 181-199.

Ratuva, S., Crichton-Hill, Y., Ross, T., Basu, A., Vakaoti, P., & Martin-Neuninger, R. (2020). Integrated social protection and COVID-19: rethinking Pacific community responses in Aotearoa. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 1-18.

Ravichandran, M., Guido, B., & Sarjit, S. G. (2018). Disaster communication in managing vulnerabilities. Malaysian Journal of Communication, 34(2), 51-66.

Reams, M. A., Harding, A. K., Lam, N. S., O'Connell, S. G., Tidwell, L., Anderson, K. A., & Subra, W. (2017). Response, Recovery, and Resilience to Oil Spills and Environmental Disasters: Exploration and Use of Novel Approaches to Enhance Community Resilience. Journal of Environmental Health, 80(2).

Rice, R. M., & Jahn, J. L. (2020). Disaster resilience as communication practice: remembering and forgetting lessons from past disasters through practices that prepare for the next one. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 48(1), 136-155.

Rohayah, S. D. S., Wafi, R. M., & Haminah, M. S. S. (2020). The Resilience of Senior Citizens in the Era of the Pandemic: A Preliminary Study During the Movement Control Order (MCO) in Penang, Malaysia. GEOGRAFI, 8(2), 110-128.

Rollason, E., Bracken, L. J., Hardy, R. J., & Large, A. R. G. (2018). Rethinking flood risk communication. Natural hazards, 92(3), 1665-1686.

Signer, J., Jonsdottir, H. R., Albrich, W. C., Strasser, M., Züst, R., Ryter, S., Ackermann-Gäumann, R., Lenz, N., Siegrist, D., Suter, A., Schoop, R., & Engler, O. B. (2020). In vitro virucidal activity of Echinaforce®, an Echinacea purpurea preparation, against coronaviruses, including common cold coronavirus 229E and SARS-CoV-2. Virology journal, 17(1), 1-11.

Shah, A. U. M., Safri, S. N. A., Thevadas, R., Noordin, N. K., Abd Rahman, A., Sekawi, Z., Ideris, A., & Sultan, M. T. H. (2020). COVID-19 outbreak in Malaysia: Actions taken by the Malaysian government. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 97, 108-116.

South, J., Stansfield, J., Amlôt, R., & Weston, D. (2020). Sustaining and strengthening community resilience throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Perspectives in Public Health, 140(6), 305-308.

Stephenson, J., Vaganay, M., Coon, D., Cameron, R., & Hewitt, N. (2018). The role of Facebook and Twitter as organisational communication platforms in relation to flood events in Northern Ireland. Journal of Flood Risk Management, 11(3), 339-350.

The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. (2013). Communication during disaster response and recovery. http://www.apnorc.org/PDFs/Resilience%20in%20Superstorm%20Sandy/Communicatio ns_Final.pdf

Ungar, M. (2011). Community resilience for youth and families: Facilitative physical and social capital in contexts of adversity. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(9), 1742–1748.

https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.027

United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction [UNISDR]. (2005). Hyogo Framework for Action 20052015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters. www.unisdr. org/wcdr/intergover/official-docs/Hyogo-framework-action-english.pdf

Wald, M. L. (April 15, 2013). U.S. rethinks how to respond to nuclear disaster. New York Times.

Wong, L. P., & Alias, H. (2020). Temporal changes in psychobehavioural responses during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia. Journal of behavioral medicine, 1-11.

Yahya, A. H., Noordin, W. N. W., & Saraswathy Chinnasamy, M. (2004). Disaster relief and preparedness; modeling crisis communication disaster intervention from 2014 flood in malaysia.

Yau, E. K. B., Ping, N. P. T., Shoesmith, W. D., James, S., Hadi, N. M. N., & Loo, J. L. (2020). The behaviour changes in response to COVID-19 pandemic within Malaysia. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences: MJMS, 27(2), 45.

Yu, M., Li, Z., Yu, Z., He, J., & Zhou, J. (2020). Communication related health crisis on social media: a case of COVID-19 outbreak. Current issues in tourism, 1-7.

Zakaria, S. A. S., Azimi, M. A., & Majid, T. A. (2014). Exploring the Issues of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Application in Disaster Risk Management: A Case Study of 2014 Major Flood Event in Kelantan. http://eprints.usm.my/41228/1/ART_109.pdf

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 January 2022

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-122-5

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

123

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-494

Subjects

Communication, Media, Disruptive Era, Digital Era, Media Technology

Cite this article as:

Noor, S. M., Mustafa, H., Rahman, N. A. A., Jaafar, M., & Chun Hou, E. N. (2022). Transcending Pandemics: Conceptualising the Centrality of Communication in Fostering Community Resilience. In J. A. Wahab, H. Mustafa, & N. Ismail (Eds.), Rethinking Communication and Media Studies in the Disruptive Era, vol 123. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 40-52). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2022.01.02.4