Abstract

The conditions of a multicultural and multilingual (the authors adhere to the publication's understanding of language as a part of the semiotic system) city with a million-plus population, which is Ufa – the capital of Bashkiria, are associated with noticeable transformations in all spheres of social life of the people who inhabit it and are affecting the state and functioning of the socio-cultural and socio-linguistic environment. The personality of the citizen in these conditions is faced with a choice of speech and behavioural alternatives. This applies primarily to young people. One of the most popular means of self-identification and self-expression in the modern world is graffiti, considered as a form of street art. This phenomenon began to draw the attention of many specialists, including art historians, philologists, sociologists, psychologists, and others. The study of graffiti as a sociolinguistic and linguoculturological phenomenon is relevant and interesting. In our opinion, the internal structure of urban discourse as an element of the linguistic and information space is heterogeneous: we can talk about the polyphony of the structure, the semantic game, the polylogue, which are formed by various encoding systems, acting according to the laws of such discourses. The authors of the article turn to the consideration of certain elements of Ufa epigraphy – graffiti common in the capital of Bashkiria, to their types and subtypes from the point of view of cultural and aesthetic charge and semiotic interpretation in the conditions of multilingualism and multiculturalism of the city.

Keywords: Colloquial speech studies, discoursivity, epigraphy, graffiti, hypertextuality, linguistic urbanology

Introduction

The Ufa urban space with intersecting multidimensional subspaces allows us to speak to us about its hypertextuality, ethno-specific discoursivity. We state that each of its elements – a sign (components of the linguistic life of the city as separate parts of linguistics (in particular, epigraphy), colloquial speech studies, social and territorial variation of the language of the city population in the conditions of bilingualism and multilingualism, specifically manifested in oral and written forms of language/speech and subsystems) – is considered in its dynamic social relations with the surrounding historical reality, the author, the recipient, etc. The present "microelement" signs, functioning with varying degrees of activity in the urban discourse coexist due to the "shimmering" multiplicity of "traces" of the simulacrum sign with the linguistic and informational objects to which it refers the citizen in the hypertextual reality.

The city is a special semiotic sphere, each element of epigraphy (for example, a sign, an inscription, graffiti) here carries the features of an urban culture. Following Lotman (1992), we propose perceiving the city as a complex semiotic mechanism, a "generator of culture", since it "is a cauldron of texts and codes, heterogeneous and multifolded, belonging to different languages and different levels" (p. 130).

Often used in the philological literature of recent years, the term "image of the city" is associated with its perception, which means:

A holistic and complex reflection of objects, situations and events that arise when a person comes into contact with them, and the reflection is caused by a number of individual psychological characteristics (memory, character, motivation), as well as a socially determined goal. (Yakovleva, 2011, p. 366)

The "image of the city" is formed as a vision of a personal worldview or its fragments, with an important role played by a word, a sign, a symbol. It is no coincidence that people have long given cities individual characteristics: (about St. Petersburg), or etc.

The sociolinguistic study of graffiti shows its socializing role in the life of a citizen; contributing to the assimilation of social norms, as well as providing information to residents about social differentiation (professional, local, age, national and language, etc.), about youth subcultures. Such local urban areas, which differ in territorial-and-landscape, cultural and status characteristics, set a particular coordinate system – the environment that citizens fill with different activities, in which the life of the city is formed in a mosaic (Salikhova & Iskuzhina, 2013, p. 186). For the sphere of philological (more broadly – humanitarian) knowledge, the novelty of the study lies in the fact that the phenomenon of graffiti as one of the most common forms of street art is revealed as the formula-code of the Ufa linguistic culture. The products of graffiti culture are considered as elements of the language landscape of the capital of Bashkiria.

Problem Statement

Within the framework of the so-called "general" graffiti in the Ufa epigraphy, such forms as graffiti-autographs, graffiti-slogans, graffiti-latrinalia (inscriptions in public toilets), student graffiti and others are preserved, as well as the characteristic functions of "maintaining the cultural and speech convention of micro- and macro-society" (Belkin, 2003. p. 7), individual and group identification, proclamation of rejection of certain socio-cultural norms, and others.

A significant part of graffiti reconstitutes traditional texts and is based on common technologies that are characteristic of the group to which the author belongs. In this regard, we consider it important to pay attention to the national and cultural images and themes that are embodied in graffiti, to determine their linguocultural characteristics;

Graffiti is characterized by a formalaicity; the texts themselves are quite stable for some popular period, so the graffiti artists act as their translators. It is necessary to ascertain which graffiti stereotypes are characteristic of those who write on the walls, taking into account their belonging to certain social, territorial, and subcultural groups. It is important to understand what, relatively speaking, linguoculturological tradition forms graffiti, within which it is more correct to talk about the image with which the creator consciously identifies himself.

Research Questions

The subject of the study was the individual elements of street art, namely graffiti, in their representation in the capital of modern Bashkiria. Graffiti as objects of the urban environment are qualified by us as experienced speech, as a hidden dialogue in the sociolinguocultural space. At the same time, inscriptions and drawings on bus stops, house walls, fences reflect "the most important spheres of urban life, starting from political, official or artistic, ending with household correspondence" (Shkolnik & Tarasov, 1977, pp. 12-13).

Without going into the specifics of the traditions of graffiti, we will consider them in the context of a fairly stable phenomenon in its forms, first of all, the youth culture, as part of a polycode graphic communication system. The term is more often "associated with obscene words on a fence or colourful painting of trams and concrete fences, but was originally introduced by researchers in this field to refer to ancient and medieval wall inscriptions and images" (Belkin, 2003, p. 5). As it transpired, the term united many forms.

- Graffiti is considered as a source of information about a particular community or ethnic group. So, Bushnell defines graffiti as means of communication of the youth subculture, through which they, on the one hand, carry out internal communication, on the other – create a communication barrier between their own community and the rest of the world (Bushnell, 1990, p. 224). On the contrary, Kowalski, considering graffiti of schoolchildren as a means of social construction of reality, defines its three functions: actuating, integrative (association into the community) and the function of development and organization of urban space (Abaeva, 2011, p. 173).

- Lurie – one of the most respected scholars in the field of graffiti studies, notes the mixing together of three different phenomena that have a common "phenomenological core", but differ both formally and functionally. This refers to (1) the well-known urban culture tradition of writing and drawing on walls; (2) the common practice of communication through graffiti; (3) the activities of graffiti artists . All known kinds of this type of street art are represented in the urban landscape of Ufa. Graffiti is considered as "a manifestation of the postmodern destructive and playful attitude to reality, as the removal of the opposition between the private and the public, the centre and the periphery, high and low, art and everyday life" (Demin & Kashkin, 2001, p. 15)

Purpose of the Study

Graffiti as a popular form of street art, giving the individual self-realization, translates their national and cultural vision of the depicted. There arises a need to study the nature of the scope and influence of this element in the structure of language and culture, to identify the main features of graffiti culture in the capital of the republic, to determine the meaning of graffiti in the culture of modern Ufa. Graffiti is quite actively included in the semiotic life of the city, so there emerged a need for a full-fledged scientific explanation of this phenomenon due to the lack of unified theoretical concepts that would ensure their objective interpretation and viability.

Research Methods

In the proposed fragment of the study, the following set of theoretical and empirical methods was used, the combination of which made it possible to study the indicated problem:

- comparative method used for classification and determining the prospects for further development of the studied phenomena;

- method of induction, suitable for the development of intermediate conclusions in the study of selected individual elements of street art in Ufa;

- descriptive method used to achieve complexity in the presentation of the material under study;

- content analysis when considering the content of the main conceptual apparatus of the study, as well as when studying the thematic areas of graffiti in the capital of the Republic of Bashkortostan;

- typological analysis for attributive structuring of the language landscape of the city of Ufa.

Findings

Researchers, considering graffiti as a specific communication system, distinguish two different types: intragraffiti (dialogue between native speakers of graffiti culture) and extragraffiti (dialogue in the language of graffiti with the "outside" world, which does not use such a graphic code of communication). The communicative nature of graffiti manifests itself at different levels. They often represent a hidden dialogue or correspondence, interpreted as an act of communication, since; like any public text, they have a potential addressee and are often embodied in directives (Figure 1).

The following areas of graffiti distribution in the modern Bashkortostan capital are distinguished: street (walls of buildings, underground passages, garages, asphalt coating in courtyards, etc.), vehicles, entrances and stairs (including apartment doors, mailboxes, etc.), interiors of public institutions, etc. On posters, ads, and billboards regularly appear edits, the authors of which try to cover as many units of text as possible with a response in the language of graffiti. Whereas previously, only texts that directly call for a dialogue (questions, appeals) or that suggest it in connection with the content or place of a scripture received a response, now any inscriptions are subject to a response: – between the second and third words at the top is written. The tendency to expand the "range of influence" is characteristic of graffiti in the communication system of modern Ufa: every inscription is interpreted as a response-provoking remark, and the entirety of urban planes turns into an epistolary space. The graffiti language, according to experts (Belkin, 2003; Fedorov; 1996, p. 8), tends to become a universal code of urban communication. Writing and drawing on the walls is a part of a combination of common communication practices among young people (such as communication in Internet chats, group actions, etc.).

Inscriptions with the expression of musical, gaming, sports, ideological or ethnic preferences and antipathies, reflecting the credo of the creator, consist of signs. This type of utterance is most typical of subcultural graffiti. A special role in the formation of the communicative code of graffiti belongs to the typical drawings-emblems that act as independent semantic units (for example, the owl – a symbol of wisdom – Figure 2), as semantic doublets of a particular word. Compasses, Whatman drawing paper on the background of geometric shapes (Figure 3) – the same as saying "I draw (I like to draw/trace/design)".

Often graffiti texts are based on a combination of them with words in one utterance or dialogue. This is due to the status of the language of emblems for graffiti: the presence of a sign in the inscription acts as a marker of graffiti discourse and evidence that the writer owns it, and therefore is involved in the corresponding culture. Drawings-signs play the role of a "trademark", identifying the writers as members of a subcultural group (Shchepanskaya, 1993). At the same time, the signature sign is often displayed in front of it, as a prerequisite for the "from" column. A more or less detailed statement-emblem acts as a kind of nominative theme – a figure of speech, in the first place of which there is an isolated noun in the nominative case, naming the topic of the subsequent phrase.

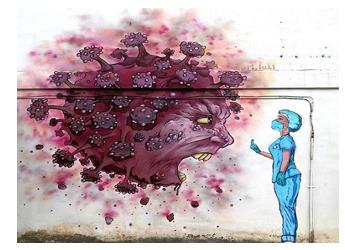

In Russian large cities, the first inscriptions and drawings made in the style of Western "professional" (or "artistic") graffiti began to appear in the early 1990s, in Bashkortostan - in the middle of the first decade of the XXI century. Groups of wall painters now exist not only in metropolises, but also in small cities. In July 2013, the Republican graffiti festival "Street Art-2013" was held in Ufa with the assistance of the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Bashkortostan; in June 2016 – the youth festival of graffiti and street art "Bright Streets", in September 2020 – the festival of street and public art "Uram–2020". The main theme of the street art festival in 2020 – unity in the fight against the new coronavirus infection. Through their graffiti, the artists convey the importance of the contribution of medical workers and volunteers to the preservation of life and health of the population, the concern of citizens for the elderly and people with disabilities, a look at new realities and the life of society in the "post-covid era" (Figure 4).

The picture shows a large evil head, stylized as COVID-19. In front of it, a medical worker in a professional uniform and medical mask stands serenely, beckoning the virus to her with her index finger. It was based on the popular online work of English cartoonist Hiblen from Norwich. In the original work, the doctor looks at the terrifying face of the virus and shows it the middle finger, indicating an obscene gesture. In the Ufa version, the middle finger was changed to the index finger. As a result, the concept of scandalous graffiti has changed to the opposite, according to famous Russian designer Lebedev.

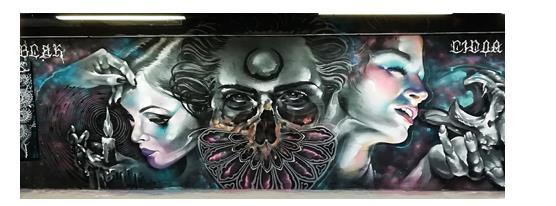

One of the manifestations of subcultural ideology and practice is (drawing graffiti in officially permitted places) and contrapositive of it – (inscriptions and drawings in public places prohibited for this purpose – see Figure 5, 6). The first one requires more artistic skill, more time to perform the work in a calm environment, in large areas, with unlimited technical capabilities. At the same time, the righters understand that the social bias of their activities is harmful for graffiti as an informal direction and that only bombing with its fundamental illegitimacy can keep the movement at the subcultural level.

Ethnospecific and regional identity is brought to graffiti by means of subjects from national culture. So, the Figure 7 shows a dancing Bashkir woman, whose image seems to be genetically related to the spatial associations of the ancient Bashkirs. In symbolic form, graffiti conveys natural images. In any case, the plasticity and mobility of the Bashkir dance can be explained, undoubtedly, by the fact that it is performed against the background of nature. Owing to the features, masterfully depicted by the artists, the plot and visual drama, functionality, as well as the stylistic, i.e. imitative, contemplative, features of traditional dance, in their organic unity, most fully reflecting the folk spirit, psychology, and mentality, are completely reconstructed at the level of perception.

A mysterious boy with a magical musical instrument beckons the guests of the capital closer (Figure 8). The drawing is expressive: white lilies can be seen from afar, as if the melody is blooming. It gradually grows out of the Bashkir flute – Kurai. Graffiti attracts attention with the simplicity of a beautiful idea to connect flowers with music. In pictorial art lilies hold a unique position. This flower has captivated artists of all times with its beauty. The pictures in which they are depicted always have some subtext that the creator wanted to convey. In "The Boy with the Kurai", the flower most likely symbolizes the innocence and purity of the player, the beauty of the melody, the sacred meaning of the music (Rogozhnikova et al., 2019). In this context, it is appropriate to recall that there is a sculpture "Boy with Kurai" – the work of Solovyova-Efimova in Ufa. High above the ground, in the centre of a huge fountain bowl, a thin bronze boy with a friendly half-smile is ready to play his favourite tunes to the Ufa residents. This is one of the best park sculptures, made in the classical traditions. The naked boy is the union of human with nature. The author of the sculpture was fascinated by the sound of the Kurai, which absorbed the music of streams, mountains, and forests… Its melodies are the music and soul of the people. And Kurai itself is the soul of Bashkortostan. Along the way, in the centre of the Bashkir capital, an unusual art object is installed – three stone balls with crossbars. This is the stylized spelling in the Bashkir language of the urbanonym "Ufa" ("Эфэ"). This image has been known among Ufa residents for a long time, and the sculpture has received a lot of positive reviews on urban planning forums. "Three screws" and similar stelae at the entrance to Ufa make up for the lack of a graffiti image of the urbanonym at the present time.

A giant portrait of the legendary pilot, two times awarded Hero of the Soviet Union Musa Gareev (Figure 9), appeared on the facade of the house on Khudayberdin Street, 4 (Musa Gareev once lived in this house) back in 2015 – for the 70th anniversary of the Great Victory. At the moment, this is the largest graffiti in Ufa. The area of the drawing is 436.5 meters, and the height of the image is 28.2 meters.

For the 75th anniversary of the Victory in the Great Patriotic War in Ufa, near the house number 3 on Rabkorov Street, there was a graffiti dedicated to the Hero of Russia, the legendary commander of the 112th Bashkir Cavalry Division Minigali Shaimuratov by artist-designer A. Milyakhov. Not far from the house 8/1 on Batyrskaya Street, graffiti appeared in memory of brutally murdered Ivan Nesmeyanov, the work of the same artist.

We are convinced that the best memory of the war is the memory of people, troubles, grief and mistakes. Precisely this kind of memory that can protect you from new tragedies. Residents of the city, the visiting audience will feel sometimes austerity, sometimes officiousness and pathos, sometimes movingness and sentimentality, sometimes kitsch and naivety. Nevertheless, the patriotic theme is in demand, which means that generations value the contribution of their grandfathers and great-grandfathers to the common cause of the Victory over fascism.

Conclusion

Sociolinguistic and linguoculturological approaches to the interpretation of graffiti as a special phenomenon of modern epigraphy consider it in the codes and in the forms of figurative activity, in the characteristic themes and in the implemented functions – communicative, representative, accumulative, aesthetic.

- The interaction of the graffiti-word and the graffiti-sign is united by the fixation on the identity of the sign with the word. Following the anthropologists, folklorists, and psychologists, we define this as a tendency to lexicalize emblematic-type drawings, and there is also a counter-tendency to emblematize the word. Repeated words and phrases that are matched with typical images in urban graffiti, are clichéd and turned into emblems.

- The main goal of the graffiti festivals is the development of street art in Ufa and Bashkiria, the improvement of the courtyard territory of the city, as well as the support of the creativity of young artists, the creation of a modern urban environment and new cultural codes with the help of graffiti art. Festivals harmoniously fit into the social environment, unite people and, accordingly, attract attention to "works of art, actualizing the aesthetic component of our life" (Bitter, 2016, p. 18).

- Righting and bombing represent two tantamount and equally necessary poles of subculture. The first one implements the idea of professionalism and the installation on the aesthetic value of the results of activity, which distinguishes graffiti among other modern youth subcultures. The functions and role of the second one are to implement the status of graffiti as a prohibited movement. Maintaining this countercultural component ensures its "competitiveness" along with other informal youth movements.

- In their works containing ethno-regional images and themes, street art artists promote humanistic values. The existence of graffiti can be represented as the realization of a special information space, since it is considered as "a means of constructing a certain socio-cultural reality – a psychosemiotic system that has a number of socio-psychological properties and forms the consciousness of individuals who fall within its sphere of influence" (Belkin, 2003, p. 5). Professionally executed giant graffiti on the facades of houses is perceived as a trademark of Ufa. In different parts of the city, you can find dozens of bright colourful drawings depicting famous personalities, historical stories, fragments of various events.

Street art certainly reflects the inner world of any city. It is generally accepted to convey the character of the city, its temper and mood. Ufa, as we have seen, is no exception.

The heterogeneity and ambiguity of Ufa street art are obvious, as well as the street art of many cities (especially in the post-Soviet space). Many of the artists reproach the graffiti artists for being crude or primitive, for the banality of certain topics, or for the rudeness of presenting them to the public, because, as professionals believe, they should be responsible to the citizens. Individual illustrations considered in the framework of this publication represent non-standard solutions in the composition, reflect the urban environment, which means that if Ufa "wants to be en rapport", it needs to focus only on the best, combining (to the best of its power and abilities) the voice of the heart with the rhythm of time.

If we recognize street art as art, then it plays a role in the aesthetic education of children, teenagers, and young people. The Ministry of Culture of the republic believes that street art is young, and it is necessary to "direct it in a peaceful direction", so that the graffiti artists are guided by good examples. It is important to develop and support graffiti artists, especially since last year in Russia and Bashkortostan was the Year of Culture. Street art has a deep potential to contribute to the creation of the cultural space of the country and our republic, especially since it is one of the most democratic forms of art. Through street art, you can facilitate and promote national, classical, and folk art, as well as the art of Ufa artists.

References

Abaeva, G. B. (2011). Scientific approaches to the study of informal graphic images and inscriptions. Bulletin of Tver State University. Series "Pedagogy and Psychology". 3, 172–177.

Bitter, M. V. (2016). Festival of street art and graffiti "Stenography" as a form of representation of contemporary art. Man in the world of culture, 2, 136–144.

Belkin, A. I. (2003). Socio-psychological analysis of graffiti (based on non-institutional inscriptions and drawings of educational institutions in Samara). Samara State Pedagogical University.

Bushnell, J. (1990). Moscow Graffiti: Language and Subculture. Boston.

Demin, A. A., & Kashkin, V. B. (2001). Interaction of language and environment in graffiti texts. Language, communication and social environment, 1, 125–135. Voronezh State University.

Fedorov, V. (1996). Petersburg graffiti. Arguments and Facts, 41(164).

Lotman, Yu. M. (1992). Semiotics of culture and the concept of text. Selected articles. Vol. 1. Tallinn.

Rogozhnikova, T. M., Salikhova, E. A., & Efimenko, N. V. (2019). Ethnocultural code of mentality through of the Bashkir associative thesaurus and colority. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences, 2677-2683. DOI:

Salikhova, E. A., & Iskuzhina, N. G. (2013). Heterogeneous linguistic space of the city: the specifics of speech contact. Philological sciences: Questions of theory and practice, 3(Part 2), 181–186. Diploma.

Shchepanskaya, T. B. (1993). Symbols of youth subculture. Nauka.

Shkolnik, L. S., & Tarasov, E. F. (1977). The language of the street. Nauka.

Yakovleva, E. A. (2011). Philological Urbanology: New Aspects of Study. Bulletin of Nizhny Novgorod University. N.I. Lobachevsky, 6(2), 771–774.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

02 December 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-117-1

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

118

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-954

Subjects

Linguistics, cognitive linguistics, education technology, linguistic conceptology, translation

Cite this article as:

Salikhova, E. A., Iskuzhina, N. G., & Karimova, G. A. (2021). Ethnoregional Elements In Ufa Graffiti Culture. In O. Kolmakova, O. Boginskaya, & S. Grichin (Eds.), Language and Technology in the Interdisciplinary Paradigm, vol 118. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 818-828). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.12.99