Abstract

The article is devoted to specifics of foreign language acquisition (FLA) and aptitude in different stages of adulthood. Based on psychophysiological and social characteristics of certain ages we classified adult learners into four age groups: 15-20, 21-35, 36-50, 50+. The goal of the study was (1) to compare the general level of the FLA barrier in all four age groups and (2) to check what types of barriers prevail in each age group. According to the typology suggested by the author, barriers were divided into 6 types: psychological, didactic, psychophysiological, linguistic, social adaptation, competence. The research consisted of two phases: the first phase implied interviews with English teachers working at Russian language schools and universities and analyzing profiles of “bad language learners” collected in the interviews; the second phase implied comparing general level of barriers and their distribution in different age groups using the author’s questionnaire “Diagnosing barriers in foreign language acquisition”. 89 barriers were analyzed in the first phase; 132 students learning English as a foreign language took part in the second phase. The research has proved that the general level of barriers does not have any strong correlation to age (the questionnaire results in all four age groups were comparably equal). However, different types of barriers were dominant in different age groups. In the group 15-20: psychological and competence barriers; in the group 21-35 and 36-50: competence barriers; in the group 50+: psychophysiological barriers.

Keywords:

Introduction

The idea of lifelong learning and growing opportunities for global communication have noticeable influenced the average age of students learning foreign languages in Russia. More and more adults join language courses either to learn a new foreign language or to enhance their proficiency in languages they studied at school. According to the poll by Russian Center of Public Opinion Research in the year 2019 26% of adult respondents were planning to take up learning a new language or to improve their knowledge of foreign languages they studied before. Among those who didn’t plan on learning languages in the nearest perspective almost every fourth respondent mentioned age or decreasing ability to memorize information (23%) (Russian center of public opinion research, 2019).

Problem Statement

Our research is devoted to barriers in foreign language acquisition (FLA). A barrier in FLA we define as student’s individual reflection of objective difficulties (linguistic, psychological, social adaptation etc.) influencing learning process.

Age is traditionally considered as FLA barrier. For instance, Critical Period Hypotheses states that “automatic acquisition from mere exposure to a given language seems to disappear [after puberty], and [that thereafter] foreign languages have to be taught and learned through a conscious and laboured effort” (Lenneberg, 1967, p. 176; Penfield & Roberts, 1959). Even though this idea did not find total acceptance in scientific circles (Boehm, 1959, Bialystok & Hakuta, 1999; Krashen et al., 1979; Shin, 1999) it is still quite popular among many foreign language teachers and students.

Research Questions

The research of the last two decades with classroom language learners has demonstrated that later starters may consistently outperform younger starters on measures of L2 achievement. An instructed setting where the target language is a foreign language gives adults a significant advantage. In the absence of high quality, large-quantity input (which is the case with natural bilingual settings), a certain level of cognitive maturity seems to be necessary for learning to be successful (Larson-Hall, 2008; Muñoz, 2010; Pryanichnikova, 2011; Sanz, 2005; Tellier & Roehr-Brackin, 2013). Besides, the advantages of adult learners are: competence in using memory strategies (Vitlin, 1978, p. 59), good memory strength and volume (Vitlin, 1978, p. 62), advanced strategies for expressing one’s thoughts verbally (also in L2) (Vitlin, 1978, p. 67), advanced strategies for handling grammar material (Vitlin, 1978, p. 86). Adults are usually more collected, they can enter into work quickly, have high endurance, big volume of attention, and greater cognitive maturity than kids (Barvenko, 2004; Kapitonova & Moskovkin, 2006; Pryanichnikova, 2011). However, late start actually does have several typical difficulties. These are difficulties in changing inner speech stereotypes (Vitlin, 1978, p. 68); big discrepancy between the range of L1 and L2 active vocabulary (Vitlin, 1978, p. 67); age changes of auditory, articulation and visual sensitivity (Vitlin, 1978, p. 81-83); such psychological factors as: psychological complexes, personal traits and attitudes, social stereotypes, difficulties to accept the status of student (Barvenko, 2004).

It all brings us to the idea that the phenomenon of the so the called “age barrier” is very complex. The research in this field can be enhanced in two directions. The first is comparing the FL performance and psychological variables of different age groups of adults (rather than contrasting just two age periods adulthood and children). The second is using a more targeted approach for diagnostics of adults’ level of FLA barriers (rather than relying on indirect indicators of a barrier (such as teachers’ empirical observations, or student’s performance in FL)).

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study is to conduct a comparative analysis of barriers in foreign language acquisition outside the language environment in different age groups of adults.

Research Methods

Following the characteristics of different age periods suggested by Vitlin, we divided adult students into 5 age groups: 15-20, 21-35, 36-50, over 50 years old. The borders of these age periods are characterized by biological changes influencing foreign language aptitude. Besides people of these ages usually take different social roles which, in turn, influences the amount of training time, the degree of student’s independence (among all financial), ability to make decisions about taking up and continuing a language course, maturity of character, specifics of psychological barriers.

The research consisted of two phases.

At the first stage, we carried out series of interviews with English teachers working at Russian universities and language schools. The teachers were asked to describe a case(s) of “bad language learner(s)” from their teaching experience. 24 teachers took part in the interviews. They shared with us stories of 41 “bad language learners”: 8 students aged 15-20, 13 students aged 21-35, 14 students aged 36-50, and 5 students aged over 50.

The second phase of the research implied studying the barriers from students’ perspective. For this purpose, we used the questionnaire “Diagnosing barriers in foreign language acquisition” (Brem, 2021, para. 7). The questionnaire measures students’ attitude towards 6 types of difficulties that accompany language learning process: didactic, psychological, psychophysiological, linguistic, competence, and social adaptation.

include competence of L2 teachers, quality of textbooks and teaching materials, effectiveness of learning program, language-learning conditions. include personal attitudes, specifics of emotional, will, and motivational spheres of a student. are constitutional predispositions influencing FLA process. relate to differences between L1 and L2 (grammar, vocabulary, phonetics etc.): possibility to make comparisons, use internationalisms, interference etc. are linked to students’ readiness (psychological, pluricultural, metacognitive etc.) for learning foreign languages: competence of students in using language learning strategies, students’ previous experience in learning languages, students’ level of education and pluricultural competence etc. are problems of adaptation to new social roles, to micro and macro environment, problems of building relationships with teacher, and groupmates.

132 students took part in the poll: 96 university students aged 15-20, 22 PhD students aged 21-35, 11 students aged 36-50 (language school), and 3 students aged over 50 (language school). The last age group was presented with just three students; we deseeded to include this data into the diagrams and tables but the results will not be extrapolated to the whole age group.

Findings

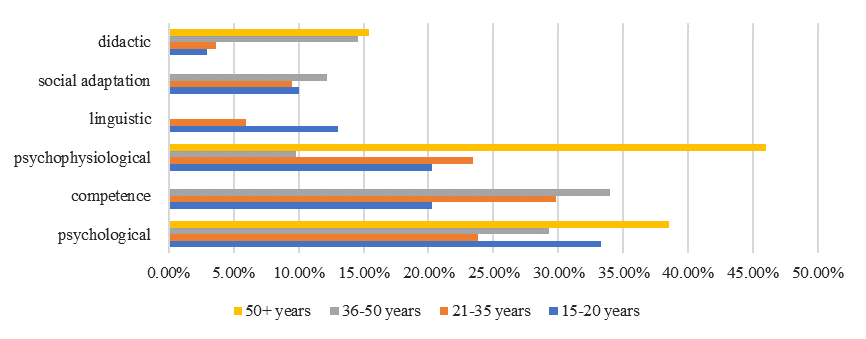

In the first phase, the analyses of the materials of interviews with teachers helped us to detect 89 barriers. Problems of students (Figure 01) were distributed as following:

The 6 types of barriers were represented with problems described in Table 01, Table 02, and Table 03.

The results of the interviews let us draw the following conclusions.

Most common barriers for the age group 15-20 are psychological, competence and psychophysiological barriers.

In the group 21-35, competence barriers take the first place, psychological and psychophysiological barriers following them.

In the group aged 36-50, linguistic barriers were absent. Competence barriers took the first place; the second place belonged to psychological barriers. Unlike the previous two age group the role of motivation barriers among psychological barriers significantly dropped.

Motivation barriers entirely disappear in the group 50+. Linguistic, social adaptation and competence barriers were also absent. At the same time, this group demonstrated the largest percentage of psychophysiological barriers (46%).

Results and Discussion

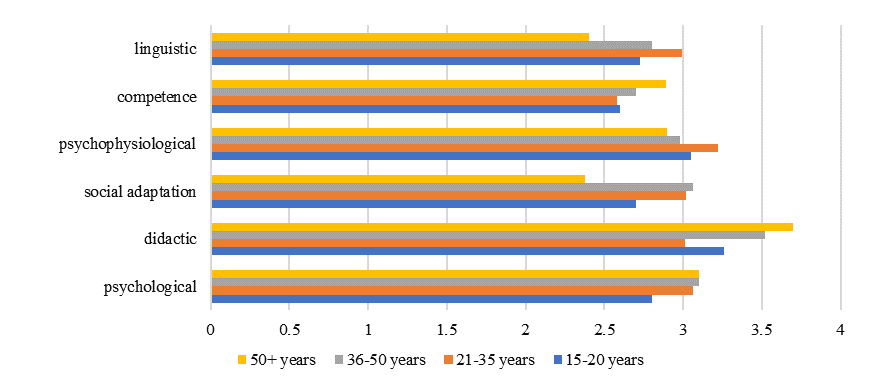

In the second phase of the experiment (figure 2), according to the poll of students, barriers were distributed as following:

The experiment rebutted the stereotype about the connection between age and language learning barriers: the general level of the barrier in all four age groups was roughly equal.

Age group 15-20 demonstrated the highest level of barrier in the scales: competence barriers (2.6), social adaptation barriers (2.7), and linguistic barriers (2.727). Psychological barriers gained 2.8 points.

In group 21-35 competence barriers (just like in the interviews) took the first place (2.58), linguistic barriers took the second place (2.99).

In group 36-50 competence barriers (2.7) and linguistic barriers (2.8) gained the highest points. This data is slightly different from the interview results, which can be explained with several reasons. First, students did not admit having problems with motivation or responsibility (mentioned by many teachers), so psychological barriers significantly lost their positions. Second, teachers underestimated the role of linguistic difficulties. Third, students’ performance in foreign languages may suffer more on social adaptation difficulties than teachers believe. The fact that didactic barriers gained more points in the poll than in the interviews was not unexpected: predictably, teachers mentioned less didactic problems than students did. Furthermore, most teachers in the interviews were working at language schools whereas the poll subjects in the first two age groups were university students and PhD students enrolled into an obligatory language program.

Conclusion

We studied distribution of different FLA barriers in the age groups: 15-20, 21-35, 36-50, 50+.

On the first stage of our research, we carried out interviews with English teachers working in Russia and collected 41 profiles of “bad language learners”. This material contained 89 barriers in FLA. Statistically, most common barriers for the age group 15-20 were psychological (33.3%), competence (20.3%) and psychophysiological (20.3%) barriers. In group 21-35 competence barriers took the first place (29.8%), psychological barriers took the second place (23.8%), psychophysiological barriers were on the third place (23.4%). Similarly, in the group aged 36-50 competence (34%) and psychological (29.3%) barriers took the first and second place respectably. Compared to the previous two age groups the role of motivation barriers significantly dropped in the group 36-50 (only 2.44%). In age group 50+ the first place clearly belonged to psychophysiological barriers (46%). At the same time motivation barriers entirely disappeared, other psychological barriers made 38.5%. Linguistic, social adaptation and competence barriers were absent.

On the second stage of the research, we carried out a poll among students learning English as a foreign language. According to the poll the general level of barrier in all four age groups made 2.8-3 points out of 4 (where 1 means “high level of barrier” and 4 means “no barrier”) which proves that there is no strong correlation between FLA barrier and age (in different age groups of adults). In age group 15-20 the following barriers were dominant: competence barriers (2.6), social adaptation barriers (2.7), and linguistic barriers (2.727). In group 21-35 competence barriers took the first place (2.58), linguistic barriers took the second place (2.99). In group 36-50 competence barriers (2.7) and linguistic barriers (2.8) took the first and second place respectively.

Comparing the results of the interviews and the poll brings us to the idea that teachers seem to underestimate the role of linguistic and social adaptation barriers and overestimate the role of motivation problems. Both methods detected the great importance of competence barriers for learning foreign languages in adulthood, so it could be advisable to make a higher stress on teaching foreign language strategies to adult learners. We are planning to continue the research: to increase the number of subjects and to precise statistics for the second and third age groups, and to collect relevant materials in the last age group. This research may help to understand better the problems of adult FL learners, hence solve these problems more targeted and more efficiently.

References

Barvenko, O. G. (2004). Psychological barriers in teaching a foreign language to adults: [Doctoral dissertation]. North Caucasian Scientific Center of Higher Education.

Bialystok, E., & Hakuta, K. (1999). Confounded age: Linguistic and cognitive factors in age differences for second language acquisition. In D. Birdsong (Ed.), Second language acquisition research. Second language acquisition and the Critical Period Hypothesis (pp. 161-181). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Boehm, L. (1959). Age and Foreign Language Training. The Modern Language Journal, 43(1), 32-33.

Brem, N. S. (2021). Questionnaire “Diagnosing barriers in foreign language acquisition”. https://dispace.edu.nstu.ru/didesk/course/show/11687/0

Kapitonova, T. I., & Moskovkin L. V. (2006). Methods of teaching Russian as a foreign language at pre-university stage. Zlatoust.

Krashen, S., Long, M., & Scarcella, R. (1979). Age, Rate and Eventual Attainment in Second Language Acquisition. TESOL Quarterly, 13(4), 573-582. DOI:

Larson-Hall, J. (2008). Weighing the benefits of studying a foreign language at a younger starting age in a minimal input situation. Second Language Research, 24(1), 35-63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43103754

Lenneberg, E. (1967). Biological Foundations of Language. Wiley.

Muñoz, C. (2010). On how age affects foreign language learning. Advances in research on language acquisition and teaching, 39-49. http://www.enl.auth.gr/gala/14th/Papers/Invited%20 Speakers/Munoz.pdf

Penfield, W., & Roberts, L. (1959). Speech and brain mechanisms. Princeton University Press.

Pryanichnikova, L. V. (2011). Psychological readiness of a child to learn a foreign language. Sibirskij pedagogicheskij zhurnal, 8, 183-190. https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/psihologicheskaya-gotovnost-rebenka-k-izucheniyu-inostrannogo-yazyka

Russian center of public opinion research. (2019). Are foreign languages a good investment? https://wciom.ru/index.php?id=236&uid=9924

Sanz, C. (Ed.). (2005). Mind and context in adult second language acquisition: Methods, theory, and practice. Georgetown University Press.

Shin, J. S. (1999). Age factor in foreign language acquisition. The Snu journal of education research, 9, 1-16. https://s-space.snu.ac.kr/bitstream/10371/70576/1/vol9_6.pdf

Tellier, A. & Roehr-Brackin, K. (2013). The development of language learning aptitude and metalinguistic awareness in primary-school children: A classroom study. Essex Research Reports in Linguistics, 62(1). http://repository.essex.ac.uk/5983/1/errl62-1.pdf

Vitlin, G. L. (1978). Teaching a foreign language to adults (issues of theory and practice). Pedagogika.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

02 December 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-117-1

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

118

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-954

Subjects

Linguistics, cognitive linguistics, education technology, linguistic conceptology, translation

Cite this article as:

Brem, N. (2021). Barriers In Foreign Language Acquisition In Different Periods Of Adulthood. In O. Kolmakova, O. Boginskaya, & S. Grichin (Eds.), Language and Technology in the Interdisciplinary Paradigm, vol 118. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 37-44). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.12.6