Abstract

The present article depicts the role of pitch movements in dubbing translation of the film from English into Russian. The special focus is placed on what implicit meaning intonation can convey. Using a comparative analysis of Australian sitcom and its Russian dubbed version, this paper tends to answer the question: whether the implicit meaning attached to the pitch contours of the original text is rendered in the target text in Russian or lost. The article analyses and discusses to what extent the implicatures in the original oral text are rendered in Russian translation or completely lost. The results revealed that a comparatively small percentage of implicatures has been transmitted and partially the loss of meaning is observed. But the findings obtained showed that viewers of the film can easily restructure the lost implicatures made by tone variations mostly due to the play of the actors and the situation on the whole.

Keywords: Audiovisual translation, dubbing, intonation, pitch movements

Introduction

Transmitting of intonation remains the most problematic area in the sphere of Audiovisual translation (hence after AVT). It is a widely held view that a few research papers show their findings in translation of pitch movements and other parameters of intonation in dubbed dialogues. It is almost certain that intonation conveys linguistic function, plays a key role in regulating discourse and serves as an important indicator of speaker’s identity, age, gender, psychological state and sociolinguistic membership (Shevchenko, 2015). Because of all these researchers have become concerned about the way foreign language speakers and listeners perceive English intonation in the translated version of the film. This concern has led to a number of investigations of transmitting English intonation into other languages. For instance, the Spanish researcher Sánchez-Mompeán (2019) contributed a lot into the area of translation implicatures made by intonation from English into Spanish. However, such research works haven’t been made so far in English-Russian translation. Baños-Piñero and Chaume (2009) indicate that intonation becomes as a super communicative device which status in translation remains unknown. Mateo (2014) also says about the crucial role of intonation in transmitting different shades of meaning and the importance of transmitting into other languages. Indeed, how the characters of the film speak explains the situation of communication and general understanding of the speech.

A much debated question is whether the difference in pitch movements in languages can influence the listeners’ interpretation. There is still uncertainty, however, whether the meaning of the sentence can be changed due to the change in pitch direction. The difference in the phonetic structure of the speech should be taken into account if we speak about different languages. As a matter of fact, English conveys more information via intonation in comparison with other languages (Wells, 2006). Studies of Hatim and Munday show the importance of acquiring the equivalent translation which requires the offsetting of the lost implications made by intonation and correspondence to the norms of the target language (TL) as well (Hatim & Munday, 2004). Moreover, as Koryachkina (2017) reported, the complete change of sound while dubbing allows altering the semantic content of the utterance and the structure of communication itself.

The present article will highlight the difficulties of transferring intonation with special concern in dubbing where the change in pitch direction immediately change the pragmatic and attitudinal functions of conversation resulting in the loss of meaning. This complexity makes this study of a special interest especially from an AVT perspective.

Problem Statement

In spoken languages, intonation serves diverse linguistic and paralinguistic functions, ranging from the marking of sentence modality to the expression of emotional and attitudinal nuances. It is Bolinger’s (1986) view when he claims that intonation is part of a gestural complex, a relatively autonomous system with attitudinal effects. Linguistic and paralinguistic meanings can add different nuances to the speaker's words depending on the context and become a rich source of information for both the addresser and the addressee. The implicatures (Grice, 1975) added by intonation can affect the content in varying degrees. When the speaker's use of intonation changes the denotative content of the original sentence, word or phrase, intonation affects propositional content. Conversely, when the speaker's intonation adds implicatures to the denotative content of the sentence, it affects presuppositional content rather than propositional one (Wennerstrom, 2001).

One major issue in Tench (1996) research concerned the fact that intonation can give meaning to the linguistic content simultaneously operating by three subsystems. Firstly, a speaker should structure the utterance by dividing it into logical parts. Secondly, he/she chooses the most prominent word, i.e. the nucleus, and last but not least, a speaker chooses a particular pitch contour. As for Wells (2006) a speaker can add implicational meaning to the utterance by simply changing the pitch of the voice.

The question has been raised that translation is not only choosing the equivalents for the TL words and phrases but also the interpretation of the meaning and adaptation it to the target audience and to the linguistic environment of the TL. Translation is about the embedding the meaning into another cultural system (Pym, 2010). Much uncertainty still exists about a dubbed translator whose task is even more complicated since he works with many signifying codes that operate simultaneously to produce the meaning. As a result of such interference of codes is the production of verbal and non-verbal signs one of which is intonation. In spite of the fact that the priority in transferring is given to the verbal content (problematic issue in the discourse of cinema) intonation is required a special attention of a translator. A translator can lose implying meaning together with the intonation. All these make intonation transferring a problematic area in translation.

Research Questions

By means of comparative analysis of intonation in two languages (English and Russian) our research tends to answer the questions: What kind of sentences can have implicatures? Are the pitch movements changed in the translation of the film? Is the meaning attached to source language (SL) intonation conveyed in TL or lost in translation?

The material for our paper is the aural and visual instances drawn from the Australian sitcom Mako Mermaids (Source Text (ST)) (Shiff & Clarry, 2013a) and their corresponding translations into Russian target text (TT). The plot of the series is based on the adventures of three mermaids and their land friend Zac who turns accidentally into a merman. In order to deprive him from his power to control the water, mermaids need to overcome different tasks.

Three episodes (3, 9 and 13) from Season one, which aired on Network Tena and Nickelodeon beginning from 2013 up to 2016 were selected arbitrarily for the comparative analysis and examined in full length. Three original and three dubbed episodes, total duration of 140 minutes, were analyzed in both languages.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this research is to find out whether the form of the nuclear tone is conveyed in translation or not and what happens if the pitch movement changes. This paper also attempts to show to what extent the implicit meaning attached to intonation is conveyed or lost in translation and to decide whether the significant variations in the meaning of tone in translation influences the denotative content of the target text.

Research Methods

Methodological Issues

From AVT perspective the study of the pitch movement was made in two stages:

1. Analysis of the ST. Each sentence from three episodes was analyzed aurally. We depicted each sentence between two horizontal lines showing the form of the nuclear tone. After that, we examined the cases of tonal behaviour (strictly on the basis of the original actors' performances) that could require special attention when rendered into the target language from a translational perspective because they may carry semantic implications: the speaker's use of intonation could change the denotative content of the original sentence or word. The focus was placed on cases in which pitch variations carry semantic implicatures.

2. English sentences which require the criterion above (semantic implicature) were compared to their counterparts in TT to make sure whether implicatures attached to the ST intonation has been transferred in the dubbed translation. The Russian sentences from this category were divided in two big groups: with transmitted meaning or with non-transmitted meaning. If the meaning attached to the intonation was not transmitted, we divided the data into two groups: (a) with no loss of information (the meaning of the tone was not transmitted in the TT but equivalence was achieved); and (b) with loss of information (the meaning of the tone was lost and equivalence was not achieved).

Findings

Quantitative results of tonal meaning predominance

While analyzing three episodes and making aural and visual analysis on contours in both languages a total of 18 instances with semantic implications were found out. They may cause problems in translation from English into Russian containing implicit information. All data are categorized into specific groups according to the main role pitch movements carries in the utterances. The quantitative results clearly illustrate that many cases of difficulties for a translator implied by intonation were carried by variations in communicative types of sentences - 77 %. Miner difficulties come from uncompleted sentences - 15 %; and only 7.6 % of cases come to tag questions.

Percentage of transmitted and non-transmitted nuclear tones

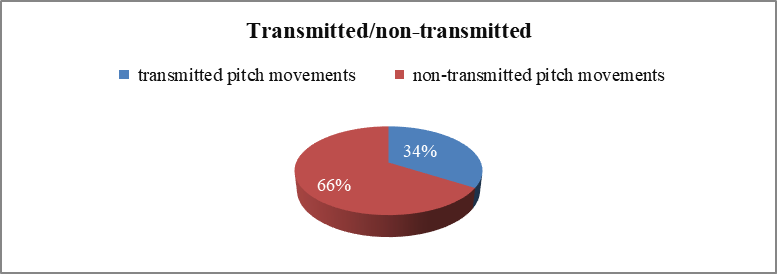

After the analysis of intonation in both languages we managed to find out as shown in Figure 1 that only in 34 % of cases the content of the message was transformed via the same use of nuclear tone. In 66 % of cases the content of the message was not transformed because there was the change in the nuclear tone. Despite remarkable high percent of ‘not transmitted’ pitch movement we can’t speak about the drastic ‘loss of information’ (only 16.5 % of instances).

The obtained results were divided into two groups whether or not the implications made by the intonation was transmitted into the target text or not. The first group constitutes the cases where intonation was managed to be transmitted into the Russian text. All implications carried by intonation in English were saved in Russian dubbed dialogues through the coincidence with the same tone or just the meaning of intonation was clear via visual code. Not transmitted instances are those which failed to reflect the meaning attached to the tonal patterns. The latter group includes two types of examples. The first subgroup shows no loss of information in spite of the loss or change of nucleus. The second subgroup includes instances which bring drastic changes in the meaning of the original character.

Non-transmitted instances with loss or no loss in meaning

Looking at the results we can see (The descriptive statistics are presented in the Table 1) that the most problematic area of using the tone in the TT are transmitting the communicative types of sentences and a lower number of problems for a practical translator is posed by tag questions. A translator managed to open all implicatures given by intonation due to the situational context.

As discussed above, the basic role of pitch movements in oral discourse is to distinguish the types of sentences. It was noticed that some changes in illocutionary force of the utterances take place in Russian language in comparison with English counterparts (in 16.5% of cases). The immediate result of such shift is the change in speaker’s intention and the aim of the utterance as well as in communicative effect. This is illustrated in the Example 1 (Shiff, 2013b) in Season 1, Episode 9. A group of three mermaids accidentally bewitch one of their land friends by means of a sirens’ song. Now he is obsessed with one of the three mermaids who has to distract him while the other two are searching for a magic shell that can break the curse. The distracting mermaid is taking advantage of the situation and the other one does not like that.

Example 1. S01 E09 (TCR: 00:17:14)

ST: 'Don’t 'take adˏvantage || Implicit information: (Polite request: I advise not to take advantage of the situation). TT: Не надо его исˎпользовать || Implicit information: (Command: Stop to use an advantage).

Here, the character, Sirena, uses the request with the rising tone to show the polite attitude to her girlfriend. In the TT a polite request of the girlfriend was changed into the declarative sentence with the falling tone in the nucleus. As a result, the request is changed into the command and simultaneously the relationships of two girlfriends are dramatically altered. Moreover, the mermaid becomes aggressive towards her loved girlfriend.

In Example 2 (Shiff, 2013c) in Season 1 Episode 9 the mermaid Lyla uses an utterance with two falling tones showing a high degree of certainty. Her words sound a matter-of-fact, she is thinking about the force of the siren’s song and her words are very similar to the command. In Russian version the actress uses two level tones in two parts of a sentence and the illocutionary effect of her words is completely changed – there is no pervasive effect.

Example 2. S01 E09 (TCR: 00.02.27)

ST: Then we can draw out his ˎpowers … the pod will come ˎback…ǁ Implicit information: I’m sure the pod will come back. TT: И тогда мы заберем у него →силу…ǀ и стая →вернется…|| Implicit information: It is possible that the pod will come back.

The next example 3 (Shiff, 2013c) in Season 1 Episode 13 illustrates the conversation about the magic force of a trident. The mermaids are not sure in the magic force of the trident but they are too willing to prevent Zac from getting the trident which can harm him or even kill him. One of the mermaids uses the question tag with the falling pitch. Thus Nixie is sure that Rita – the principal of the school, the former mermaid, can’t speak for sure about the magic spell of the trident.

Example 3. S01 E13 (TCR: 00:03:21)

ST: You don’t actually know, ˎdo you? ǁ Implicit information: You don’t know about the magic spell of the trident. TT: Ты же сама точно не ˏзнаешь? ǁ Implicit information: Do you know?

The next example is the illustration of the change of the communicative type of the sentence. In ST there is an exclamation (with the negative verb) and in TT it returns into a question. Nixie suggests giving the trident to Zac. Such an offer seems to mermaids as unbelievable and incredible. One of the mermaids expresses her indignation with the exclamation but in Russian translation the implicit meaning of incredible situation was lost.

Example 4. S 01 E13 (TCR: 00:02:16)

ST: Nixie. You can’t be `serious || Implicit meaning: You’re saying nonsense! It’s impossible! TT: Никси, ты ˏсерьезно? ǁ Implicit meaning: If you’re believing in the situation, we can try.

Conclusion

The present paper tends to find out the function of the pitch of the voice to be the means to express the additional shades of meaning and potentially be the means to resolve the ambiguity. According to our findings, the dubbed dialogues are characterized by a high percent of non-transmitted pitch movements. We found out that in oral discourse especially in the dubbed translation there is a wide range of communicative types of sentences which can possess difficulties for a translator of AVT.

For both languages various means of expressing emotions are required, thus demanding the translator thinks about not only what the characters say but as well as how they say. As results show only in 34 % of instances the pitch variations were rendered in TT whereas in 66% of instances there was the loss on a nuclear tone. However, as results illustrate that in 49.5 % of instances with a loss of nucleus in TT there was not a loss of equivalence where the viewers can catch the implicit meaning of a sentence due to visual code. And only in 16.5 % of instances there was a complete loss of meaning where even the denotative content of the sentence is changed.

Our research showed that the transferring of meaning made by tone presented difficulties in translation. The change in pitch in TT can cause the change of the speaker’s attitude, lead to undesirable associations as well as changes of the communicative intention of the speaker. Only good knowledge of meaning of English tones might be the key to produce pragmatically efficient text in other language.

We also found out that despite the case of the loss of nucleus, viewers of the film can easily recover the lost implicatures made by tone variations mostly due to the play of the actors and the situation on the whole.

References

Baños-Piñero, R., & Chaume, F. (2009). Prefabricated orality: a challenge in audiovisual translation, inTRAlinea, special issue: The Translation of Dialects in Multimedia. http://www.intralinea.org/specials/article/1714

Bolinger, D. L. (1986). Intonation and its Parts. Melody in Spoken English. Stanford University Press.

Grice, H. P. (1975). Logic and Conversation, in P. Cole & J. L. Morgan (Eds.), Syntax and Semantics (pp.41-58). Academic Press.

Hatim, B., & Munday J. (2004). Translation. An advanced resource book. Routledge.

Koryachkina, A. V. (2017). Angloyazychnyy khudozhestvennyy kinodiskurs i potentsial ego interpretativno-kommunikativnogo perevoda [English-language feature film discourse and translation of the potential ego interpretative-communicative]. [Dissertation].

Mateo, M. (2014). Exploring Pragmatics and Phonetics for Successful Translation. Vigo International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 11(1), 111-135. https://www.researchgate.net/journal/Vigo-International-Journal-of-Applied-Linguistics-1697-0381

Pym, A. (2010). Exploring translation theories. Routledge.

Sánchez-Mompeán, S. (2019). The Translation of Pitch Movement in Dubbed Dialogue. New Voices in Translation Studies, 21, 93-125. https://www.iatis.org/index.php/new-voices-in-translation-studies/item/2126-new-voices-in-translation-studies-21-2019

Shevchenko, O. G. (2015). Sociolinguistic Perspective on Teaching English Intonation for Adult Learners. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 200, 607–613. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282314167_Sociolinguistic_Perspective_on_Teaching_English_Intonation_for_Adult_Learners

Shiff, J. M., & Clarry, E. (2013a). Mako Mermaids [Motion picture]. Network Ten and Nickelodeon.

Shiff, J. M. (2013b). The Siren [Television series season 1, episode 9], in J. Shiff (Producer) Mako Mermaids. Network Ten and Nickelodeon.

Shiff, J. M. (2013c). Betrayal [Television series season 1, episode 13], in J. Shiff (Producer) Mako Mermaids. Network Ten and Nickelodeon.

Tench, P. (1996). The Intonation Systems of English. Cassell.

Wells, J. (2006). English intonation: An introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Wennerstrom, A. (2001). The music of everyday speech. Oxford University Press.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

02 December 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-117-1

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

118

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-954

Subjects

Linguistics, cognitive linguistics, education technology, linguistic conceptology, translation

Cite this article as:

Shevchenko, O. (2021). Intonation Transferring: An Analysis Of Pitch Movements In Dubbed Translation. In O. Kolmakova, O. Boginskaya, & S. Grichin (Eds.), Language and Technology in the Interdisciplinary Paradigm, vol 118. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 165-172). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.12.21