Abstract

The presented paper deals with tax systems among the states of Visegrad group. Taxes are the most important and at the same time the largest item of state budget revenue. Each state must address how to adjust its tax system to meet the needs of its citizens. Some countries are more in favour of a social arrangement, where the state provides a large number of services for its inhabitants and provides them with various forms of support. Other countries tend to be more liberal and thus provide only the minimum necessary public services. The aim of the paper is to analyse, synthesize knowledge and then compare tax systems in selected countries of Visegrad group, including the formulation of proposals streamlining tax systems. The paper is composed of four chapters. The first chapter contains an introduction to the topic and also basic literature review made for this purpose. The content of the second chapter deals with research methods used within the framework of presented paper. For this purpose, we used some simplifications and oriented mainly on the analysis of individual tax payers. Third part is mainly oriented on discussion, analysis and potential impact of these individual taxes on tax payers in these countries. It also contains specific examples of tax calculations to compare its impact between them. The last part contains results of beforementioned comparison as well as some recommendations for analysed tax systems. It also highlights legal limitations resulting from their participation in European union.

Keywords: Comparison, personal income tax, tax system, tax principles, visegrad group

Introduction

Tax policy and taxes are given different and special attention in each state, as they form an essential part of the organization of society. Tax theory tries to characterize individual types of taxes and also to determine their impact on the state economy and business entities (Bielikova & Stofkova, 2010).

Taxes are an area that we can call an intersection between the public and private sectors. On one side, they relate directly to public finances, as they are the most important revenue of public budgets. However, on the other side, they also influence households and businesses to a large extent, because it is these entities that bear the tax burden and are also their payers (Ionescu, 2020b).

There are several approaches to defining the term tax. We most often encounter the fact that the tax is defined as "mandatory, non-refundable, non-purpose, non-equivalent and statutory payment from tax subjects to the public budget" (Hunady & Istok, 2020, p. 25). At the same time, the tax is repeated regularly and usually at certain intervals, but it can also be irregular, paying only under certain conditions and circumstances. In this case, non-purpose means that it is not determined in advance which public expenditure (or, in particular, which public good) will ultimately be financed from a specific type of tax revenue. The tax revenue that has been collected can then be used, for example, to finance education, health care or defense, as well as the salaries of tax administration employees. By non-equivalence we mean that the ratio between the benefit that a person has from consumed public goods and the sum of tax that a particular person pays may not be maintained (Raisová et al., 2020).

As taxes are a type of public revenue, we believe that in order to better understand the definition of tax, it is necessary to briefly explain their nature and then characterize their individual components. Public revenues are understood by most authors as revenues of public budgets for financing public expenditures, through which the implementation of public sector activities is ensured. Public revenues are obtained by the public sector from various entities, from state-owned enterprises, from the population, from budgetary and contributory organizations, or even from abroad (Vagner, 2021). At the same time, public revenues are a decisive source of coverage for public expenditures. The lack of other public revenues and taxes in comparison with public expenditure will be reflected in the deficit or deficit of the public budget in the budget period (Ionescu, 2020a).

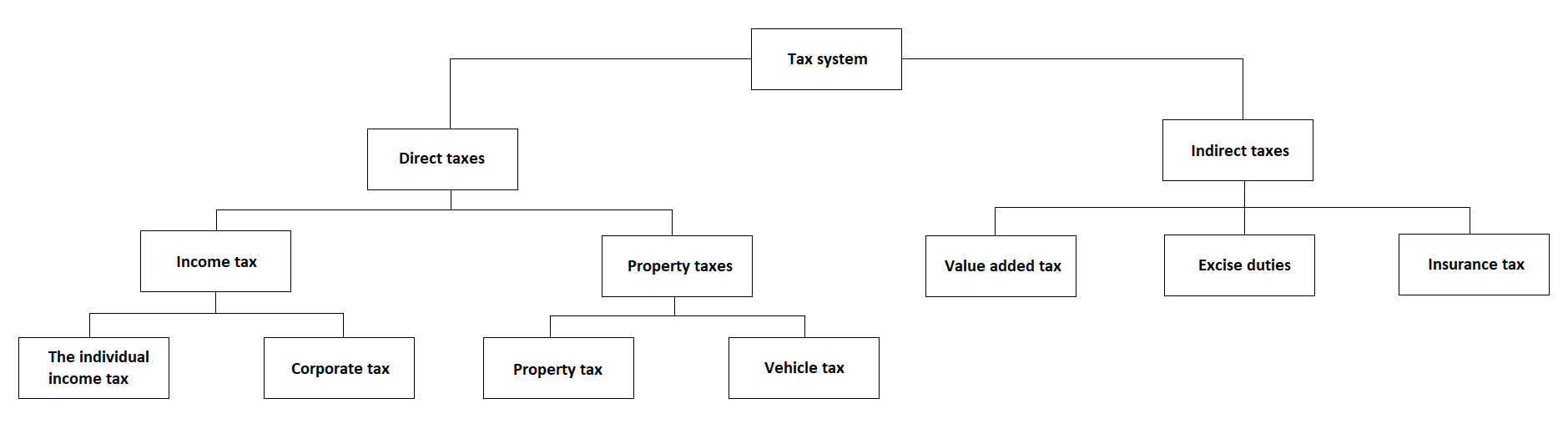

One of the basic divisions of taxes is the classification of taxes according to the link to income, respectively according to the impact of the tax. According to the above criterion, we can divide taxes into direct and indirect taxes. Direct taxes “are those where the taxpayer is also the bearer of the tax burden. Thus, direct taxes are paid directly by the taxpayer at the expense of his pension and cannot be paid transfer to another entity” (Kliestik et al., 2020, p. 82).

This is clear and a clear definition of the person liable to pay the tax. As an example of direct taxes, we can mention for example income taxes or property taxes. Indirect taxes "are those taxes for which the definition of the taxpayer is indirect, because it is not determined and possible to appoint a taxpayer in law” (Lenartova, 2009, p. 32).

In the mechanism of taxation, i.e. in the collection and regulation of indirect taxes, they are the bearer of the material burden and the taxpayer two different persons. In the given process, the taxpayer acts as an anonymous consumer who, however, pays the tax already in the price of the purchased goods or services, whereas the tax is already part of the consumer price and, on the other hand, it is the taxpayer who is designated by law as a tax collector, and may be represented by a natural person or a tax collector a legal entity, which, however, must pay the tax to the state budget (Kiselakova et al., 2020) Among indirect taxes we include selective excise and universal excise taxes. Universal taxes are imposed on global consumption, i.e. on all goods and services, as opposed to selective ones taxes, where only selected goods and services (Svabova et al., 2020). An example of a selective tax is excise duties and universal is VAT, i.e. value added tax. Figure 01 shows the classification taxes in the tax system of the Slovak Republic, which is valid for 2020.

Research Methods

Practical use of tax instruments to influence social and economic processes in society can be termed tax policy. The subject of tax policy is the application of principles and principles in the functioning and creation individual tax systems, comparison of individual tax systems on national level and their interactions. Really applied tax policy instruments to a large extent depend on the overall setting of the state's economic policy as well we consider it important to state that tax policy should apply tax principles (Jacobs, 2018).

In addition to tax principles, tax policy should also respect the principle of taxation load capacity. This principle speaks precisely that the country's tax policy should be set up in such a way as to ensure sufficient public income at all times budgets, to cover public expenditure as well as the tax burden taxpayers adequately with regard to their current solvency (Khuong et al., 2020).

Tax burden it also depends to a large extent on the scope of functions and the size of the public sector in the economy. From a macroeconomic point of view, we can monitor the country's tax burden through various indicators. Among the most frequently used indicators are tax quotas. The aggregate indicator of the tax burden is tax quota I., which can be expressed as the share of all tax revenues of a given country for the observed period to gross domestic product, i.e. the GDP of the country in the same period (Williams, 2014). Tax quota II. monitors and evaluates the tax burden more comprehensively, but to the denominator it shall also add the social security contributions paid. The given indicator is most often used for international comparison of the total tax burden in the country. Among the countries with the highest tax burden, which we rank among the most economically advanced, we can include Denmark, France, Norway, Sweden, Belgium and among the countries with a low tax burden we can rank the countries Ireland, Switzerland, USA, Singapore or North Korea. We can attribute the given cultures in particular countries with cultural differences and different citizen's priorities (Fialova & Folvarcna, 2020). If we assessed the tax burden on a global scale, with a few exceptions they have very low tax quota just developing countries.

Results and Discussion

In this part of paper, we deal with the analysis of tax systems in the Slovak republic, Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland, i.e. the Visegrad Four countries. We focused on the major part on individual income tax. The Visegrad Four (abbreviation V4) represent in a certain way informal group of countries. These are the countries of the European Union, forming an informal structure, as the countries have a common geographical position, a common history and recognize the same culture and values. Even today, the cooperation of Visegrad four is further developed, in particular through the coordination of foreign policy positions, sectoral policies and the promotion of societal interests in the European Union as well as in relation to third party countries (Burak & Nemec, 2018). The activities carried out by the Visegrad Four are mainly focused on consolidating stability in the Central European region. The main goal of the grouping The Visegrad Four is to cooperate with all countries, as well as to encourage optimal cooperation with its neighbours and neighbouring countries. In the following subchapters we will present the tax systems of individual countries, the values given represent the current values for 2021 for each country.

The above-mentioned countries have the same definition within the basic terms, namely the subject of tax, tax subject, taxpayer, tax base and tax period, but the filing of tax returns is the same in Slovakia and the Czech Republic, namely March 31 of the year following the end of the tax period, Poland has a deadline of 30 April and Hungary a deadline of 20 May of the year following the end of the tax period. However, tax rates and the tax bonus vary considerably from country to country. The tax bonus is different in countries only from the point of view that each country has a different sum according to the number of children in the family. The Slovak Republic does not distinguish how many children are in one family, but the sum is set at € 278.64 per year per dependent child. In the Czech Republic and Hungary, this system is the same, so the sum is given for the first, second child and three or more children, the sum for each group of children being different, see table 01. In Poland, the first and second dependent children are set at the same level sums and for three, four or more children the sum is determined separately, see table 01.

The tax rates in each of these countries are relatively different. In the Slovak Republic, the tax rate is 19% of the part of the tax base that is less than or equal to the sum of € 37,981.94 per year or 25% of the part of the tax base that exceeds the sum of € 37,981.94 per year. In 2021, the Czech Republic underwent significant changes in terms of tax levies and the wage calculation itself. The super-gross wage was abolished and a tax rate of 15% was set on the part of the tax base that is less than or equal to CZK 141,764 per year, 23% on the part of the tax base that exceeds CZK 141,764 per year, bringing the system closer to the system in countries Of the Slovak Republic and Poland. In Poland, the tax rate is 17% of the part of the tax base which is less than or equal to the amount of PLN 85 528 per year, 32% of the part of the tax base which exceeds the amount of PLN 85 528 per year. In Hungary, the tax rate is set at 15%.

The lowest tax, with a set gross salary of € 19,500, is paid by an employee in the Slovak Republic, namely € 2,351.35. The tax rate in the Slovak Republic is 19%. The amount of tax that an employee pay is lower in the Slovak Republic than in Hungary, where it is specifically € 2,383.87, although the lower tax rate is in Hungary and represents only 15%. This is mainly due to the fact that Hungary does not apply any discounts to the taxpayer, while the Slovak Republic does, and that is why the resulting tax is lower in the Slovak Republic. The Czech Republic underwent significant changes in 2021, abolishing the super-gross wage and introducing a division into tax rates conditioned by the sum, similar to the Slovak Republic. In the Czech Republic, the tax liability of an employee with a gross salary is € 19,500, € 87.99 higher than in the Slovak Republic at a tax rate of 23%, as the sum exceeded the set amount of CZK 141,764 for the application of 15% tax. In Poland, the tax paid by an employee is the highest among the countries mentioned, summing up to PLN 4,080.64. This is mainly due to the fact that the highest tax rate in Poland is 32%, after exceeding the set sum of 85 528PLN. The highest net salary is in the Slovak Republic, namely € 14,535.65. In the Czech Republic, the employee's net salary represents € 13,614.67, which is € 920.98 less than in the Slovak Republic. In Poland, the net wage is the lowest, at € 12,745.91, which was caused by the highest tax rate among all the mentioned countries. In Hungary, the net wage is € 13,508.62, which is € 106.05 less than in the Czech Republic.

Conclusion

Based on a tax system’s comparison of the Visegrad Four members, performed in the previous part of paper, focused on personal income tax we found out that individual tax systems of analysed countries, have positive but also negative aspects. The choice of tax liability of the employee generally has in selected countries of Visegrad Four is mainly affected by the sum of gross wages themselves (Burak & Nemec, 2016). Set tax rates and the application or non-application of various taxpayer reliefs had minor impacts. In the case of self-employed person, the sum of net income and tax liability is primarily affected by the rate taxes, the type and sum of expenses claimed and the sum of the rebate of the taxpayer.

In the end, it is possible to state that despite many differences between these countries, the personal individual income tax in the Visegrad Four countries doesn’t differ too much. This is because of common history, region and above all participation in European which has significant legal impact on the tax systems of its members.

Acknowledgments

The paper is an output of the science project VEGA 1/0210/19 Research of innovative attributes of quantitative and qualitative fundaments of the opportunistic earnings modelling which authors gratefully acknowledge.

References

Bielikova, A., & Stofkova, K. (2010). Dane v teórií a praxi [Taxes in theory and practice]. Žilinská univerzita v Žiline.

Burak, E., & Nemec, J. (2016). Main factors determining the Slovak tax system performance. In: Nicpacee Journal of Public Administrtion and Policy, 2, p. 185. De Gruyter Open LTD, Warsaw, Poland. DOI:

Burak, E., & Nemec, J. (2018). Comparative analysis of the on-job training for tax officials in V4 countries. Published: Teaching Public Administration.

Fialova, V., & Folvarcna, A. (2020). Default prediction using neural networks for enterprises from the post-soviet country. Ekonomicko-manazerske spektrum, 14(1), 43-51. DOI:

Hunady, J., & Istok, M. (2020). Daňový system [Tax System]. EQUILIBRIA, s.r. o.

Ionescu, L. (2020a). Digital Data Aggregation, Analysis, and Infrastructures in FinTech Operations. Review of Contemporary Philosophy, 19, 92–98. DOI:

Ionescu, L. (2020b). The Economics of the Carbon Tax: Environmental Performance, Sustainable Energy, and Green Financial Behavior. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations, 12(1), 101–107.

Jacobs, B. (2018). The marginal cost of public funds in one at the optimal tax system. In Int Tax Public Finance (pp. 883 – 912). Springer. DOI:

Khuong, N. V., Liem, N. T., & Minh, M. T. H. (2020). Earnings management and cash holdings: Evidence from energy firms in Vietnam. Journal of International Studies, 13(1), 247-261. DOI:

Kiselakova, D., Stec, M., Grzebyk, M., & Sofrankova, B. (2020). A Multidimensional Evaluation of the Sustainable Development of European Union Countries – An Empirical Study. Journal of Competitiveness, 12(4), 56–73. DOI:

Kliestik, T., Valaskova, K., Lazaroiu, G., Kovacova, M., & Vrbka, J. (2020). Remaining Financially Healthy and Competitive: The Role of Financial Predictors. Journal of Competitiveness, 12(1), 74. DOI:

Lenartova, G. (2009). Daňové systémy [Tax Systems]. EKONÓM.

Raisová, M., Regásková, M., & Lazányi, K. (2020). The financial transaction tax: an ANOVA assessment of selected EU countries. Equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy, 15(1), 29-48. DOI:

Svabova, L., Kramarova, K., Chutka, J., & Strakova, L. (2020). Detecting earnings manipulation and fraudulent financial reporting in Slovakia. Oeconomia Copernicana, 11(3), 485-508. DOI:

Vagner, L. (2021). Public awareness of circular economy: Case of Slovak Republic. Ekonomicko-manazerske spektrum, 15(1), 97-110. DOI:

Williams, C. (2014). Policy Appoaches Towards Undeclared Work: A Conceptual Framework. In: University of Sheffield, UK. 63. p. 30-45. DOI:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 December 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-120-1

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

121

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Ed.

Pages

1-286

Subjects

Strategic management, Leadership, Technology, Sustainability, Society 5.0, New strategic challenges

Cite this article as:

Kollar, B. (2021). Comparison Of Tax Systems In The Region Of Visegrad Group. In M. Ozsahin (Ed.), New Strategic, Social and Economic Challenges in the Age of Society 5.0 Implications for Sustainability, vol 121. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 174-180). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.12.04.18