Abstract

This article is written in line with new directions of modern linguistics – linguistic personology, cognitive linguistics, cultural linguistics, linguistic conceptology. The authors consider the basic concept of linguistic and cultural type as a typical linguistic personality of a recognizable representative of a specific ethnic and social group. The subject of the article is the linguistic and cultural type "Russian emigrant", which is a hyponym for the popular linguistic and cultural type “emigrant” and a hyperonym for the key linguistic and cultural type “Russian émigré writer” in the linguistic culture of the Russian emigration. The article presents the linguistic and cultural type “Russian emigrant” as a frame ethno-specific concept, verbalized in the works of Russian émigré writers of the first and second waves. The material of the research, therefore, is the literary texts written by Russian émigré writers in the 1920-1940s. Fragments of works by two hundred authors containing a description of the linguistic and cultural type "Russian emigrant" are analysed. The article describes the conceptual component of the specified linguistic and cultural type, its nuclear (including neutral names and figurative nominations that are synonymous with the name of the linguistic and cultural type in the studied works) and peripheral (composed by figurative comparisons) zones. The associative and evaluative component of the linguistic and cultural type "Russian emigrant" is characterized. The article can be of interest for researchers dealing with the problems of language and culture, ways of verbalization of cultural phenomena in national linguistic cultures.

Keywords: Linguistic and cultural type, linguistic cognitology, linguistic personology, Russian émigré literature, Russian emigration of the first and second waves

Introduction

The change in the scientific paradigm at the end of the XX-beginning of the XXI century made the speaker the focus of scientific attention. This led to the relevance of studying the phenomenon of linguistic personality, since "understanding of the complexity of linguistic and cultural ties led to the emergence of a new direction of linguistic research, concentrating around the triad language, national identity, culture" (Nurmoldayev et al., 2020, p. 190). In the 1950-1960s, this phenomenon has become widely studied, and therefore a separate area of linguistic research – linguistic personology- emerged. It is focused on a wide range of phenomena, including typical, recognizable collective images of representatives of a certain linguistic culture, i.e. linguistic and cultural types (hereinafter-LCT).

The LCT theory continues the theory of language personality, which is related to the understanding of the human phenomenon in language. In the concept of LCT, typicality, generality comes to the fore, and in this sense, LCT can be called a linguistic personality typified in the cultural aspect: “The link between language and identity is a phenomenon that cuts across geographical boundaries and nationalities” (Hezaveh et al., 2014, p. 2-3).

In the article, LCT is understood as the basic national-cultural prototype of a native speaker of a certain language, a representative of a certain ethnic and social group (Karasik, 2002, Karasik & Dmitrieva, 2005), which is distinguished on the basis of relevant characteristics, typical signs of verbal and nonverbal behavior of a particular language personality (Dubrovskaja, 2017; Vasileva, 2010).

The theory of LCT corresponds to the current principles of language research-integrativity, anthropocentricity, communicativeness, dialogicity (Maslova, 2018, p. 172).

The term "LCT" is relatively young, since it was introduced in the early 2000s. In fact, LCT is a special type of concept, specifically the concept which contains the person as its content. This term turned out to be quite fruitful, and became the basis of scientific research on various types of LCT. As Dubrovskaya points out, over the past twenty years, about 100 different LCTs have been described (Dubrovskaja, 2016, p. 364): "bohemian man" (Dubrovskaja, 2017), "intellectual" (Bobyreva & Dmitrieva, 2018).

The concept of LCT differs from related terms - "role", "stereotype", "image", "role", "character", "model personality", "speech portrait" in that it correlates with specific recognizable people, does not differ in super-stability, sometimes contradicting reality, as a stereotype, is characterized by versatility (in contrast to the role and image), but is not an outstanding personality as, for example, model personalities (see more Lutovinova, 2009).

Problem Statement

The study of the linguistic and cultural type "emigrant" is relevant because of the increased attention to migration issues at the present time, as evidenced, inter alis, by the data of national languages. The concept of emigrant is related to the concept of migration, which, in turn, is complex and has different sides: "Migration can be broadly defined as some form of movement of people that these accomplish over a certain distance and time" (Schmolz, 2019, p. 422).

Among the features of the linguistic and cultural type "emigrant", scientists point out the following:

As a social phenomenon, an emigrant is a person who is at the intersection of two cultures – native and foreign. Such a borderline position of the linguistic personality can lead to both full or partial assimilation in the new cultural environment, and the marginalization of the individual (Lushnikova & Starceva, 2012, p. 1470).

The LCT "Russian emigrant" is an ethnospecific LCT, since the attitude towards people who voluntarily or forcibly left their homeland differs in different linguistic cultures. In addition, this LCT has dynamic characteristics, since individual conceptual, evaluative features of this concept become more or less significant in a given time period.

The relevance of the LCT “Russian emigrant” is stipulated by its nature, on the one hand – it is related to the communicative relevant concepts; on the other – be the research material – the works of Russian émigré writers (these works are now actively studied, included in manuals and textbooks on language and literature for both Russian and foreign students).

As we can see from the graph, the peak frequency of the use of the lexeme in Russian texts falls on the 1920-1940s, when emigration became a mass phenomenon and divided Russian society into two groups – us and them.

In this article, the LCT "Russian emigrant" will be modelled on the material of poetic texts of Russian émigré writers of the first (1920s) and second (1940s) waves. It was this time period when the concept "emigrant" acquired the features of a concept, political, sociological and cultural significance (Cohen, 2008).

The novelty of the present study is that the specified LCT has not yet become the object of conceptual analysis on the selected material.

The LCT Russian emigrant is a key concept for Russian emigre literature, since it is associated with the general perception of the world, the perception of oneself in the space of a different linguistic culture. Its peculiarity lies in the fact that this LCT is depicted as if from the inside, since the writers did not observe it from the outside, but conveyed their own feelings.

Research Questions

The research questions of the article are:

1. What are the specific features of the LCT “Russian emigrant” verbalized in the texts of the first and second wave of Russian émigré literature?

2. What are the conceptual components associated with the ways of nominating the key lexeme in the texts under study?

3. What associations of the LCT "Russian emigrant" are included in the associative field of this LCT in the works of Russian émigré writers of the first and second waves?

4. What is the evaluation component of the LCT "Russian emigrant" in the texts that became the material of the study?

Purpose of the Study

The main purpose of the research is to present a model of the concept "Russian emigrant" based on the texts of Russian emigrant writers of the 1920s and 1940s.

Research Methods

The research methods include:

- descriptive-analytical method for systemizing scientific ideas about LCT in modern linguistics;

- the method of component analysis for representing the lexical meaning of the word-name of the LCT "emigrant" (according to the dictionaries of modern Russian language);

- a method of semantic-cognitive analysis, including techniques of cognitive interpretation and modeling. Modeling involves the description of the macrostructure of the LCT, its categorical structure, and the field organization of the identified categorical features (Babushkin & Sternin, 2018). The procedure for verifying the obtained data, which involves an associative experiment with native speakers, was not carried out, since the study did not include a comparison of the LCT "Russian emigrant" in the 1920s and 1940s with its modern content;

- method of linguoculturological analysis of a literary text.

Findings

The LCT "Russian emigrant" is a frame concept in its structure, i.e. a multicomponent mental formation that reflects total knowledge about the phenomenon.

The LCT “Russian emigrant” is the result of Russian émigré writers’perception of their place in the changed world, so its description will be the key to a deep understanding of the works of the representatives of Russian émigré literature. Of course, for them, emigration is not just a change of residence, it is a special existence in a special space.

According to explanatory dictionaries and dictionaries of foreign words, the lexical meaning of the word "emigrant" is formed by the phrase "relocation to another country". It is this seme that is noted in the dictionaries of the late XIX - early XX century (Chudinov, 1910; Mihelson, 1866, i.e. this meaning was relevant for the word "emigrant" when émigré writers of the first and second waves wrote their texts. In the dictionary of Dahl (1880), the lexical concept of this lexeme additionally includes the seme 'mostly for political reasons'. Thus, at the end of the XIX-beginning of the XX century, the word "emigrant" referred mainly to a person who left the Fatherland mainly for political reasons. It was only later that the lexical concept of the lexeme was clarified by specifying the reasons for emigration, as well as its forced or voluntary nature: in the dictionaries of the early XXI century, the lexical concept was supplemented with the semes 'voluntarily’,' forced’, 'for economic reasons’, 'for religious reasons', 'for political reasons' (Big Dictionary of Foreign Words, 2003; Komlev, 2006, etc.).

The conceptual component of the studied LCT is represented by a neutral lexeme "emigrant": "With the damned fate of an emigrant / I'm dying..." (Ivanov). However, lexemes in figurative meanings prevail; they metaphorically actualize the essential features of this LCT. Metaphors often act as euphemistic substitutes for the key lexeme - the name of the LCT 'emigrant'. In addition, metaphors specify the dictionary meaning of the key lexeme.

Firstly, metaphors - occasional synonyms of the lexeme "emigrant" contain the seme ‘involuntarily, unwillingly’. The metaphors of this group "hostage", "prisoner", "captive" actualize the frames "Prison", "Captivity" in the reader's mind: "The hostage has a singing dream // About the native and God-given language" (Golenishchev-Kutuzov); "the prisoner" (Kondratyev); "In the next house / / The same prisoner / / As me, who lost / / Its Native land" (Balmont). The same seme is contained in the word "exile", which also acts as a contextual synonym for the lexeme "emigrant": "The distant City of Peter, you are in my exile..." (Kondratyev); "I am afraid to begin, I am cut down by exile" (Nesmelov), "About the fate of the sad exiles " (Nesmelov), "But somehow sad exile..." (Krotkova). These images are supported by the words "imprisonment", "slavery": "Here is imprisonment / / Our fate" (Otsup); "Faith, this form of captivity, / / Chosen voluntarily" (Otsup).

The semantics of negation, emptiness, and deprivation is reflected at the word-formation and morphological levels: in the abundance of negative particles, pronouns, the word "no", the preposition "without", and the corresponding prefixes: "Helplessly wants to love, / / Pointlessly seeks to forget" (Adamovich); "without strength, without money, / / Without love, / / In Paris" (Adamovich); "And I don't need anything in Paris" (Balmont); "It's good that there is no Tsar. // It's good that there is no Russia. // It is good that there is no God" (Ivanov); "You will not dispel // The Impenetrable darkness" (Rathaus).

Secondly, by means of the lexemes "wanderer" (‘a person who constantly wanders, does not find a place in life’), "pilgrim" (‘a wandering person (usually homeless or persecuted)’) the seme ‘aimlessness of existence’ is emphasized:" There is no more joyful fate-to become a wanderer" (Adamovich); " Now I am a guest, and the lot takes me away / / Further and further the wanderer in exile..." (Olenin).

The negative connotation of these lexemes is felt when comparing them with the neutral lexeme "traveler", which is not used by writers in relation to emigrants.

The dominant emotion associated with the LCT "Russian emigrant" is the fear of the future: "I am afraid to look ahead" (Rathaus); "The coming day is only a story of new troubles" (Bim); "For people without tomorrow" (Brand).

In the opposite part, there are lexemes that actualize this ‘bearers of the great mission’, first of all, “the chosen one”: “We are the chosen ones of great grief” (Nesmelov); “And the chosen ones-the Russian people-will ask / / All the accused Russian people” (Severyanin, “People's Court”). In the latter context, the frame “court” is actualized, with the emigrants as accusers, and the Russian people who allowed the exile as the accused. The name “chosen one” is associated with the phytomorphic metaphor “the blossom of the fatherland”: “The blossom of the bright culture of the Fatherland” (Severyanin).

The motif of martyrdom is associated with this seme, supported by the subjective and mythological code: “Clearly then you will see a wooden cross and a crown of thorns” (Adamovich).

On the periphery of the conceptual component, we find words denoting linguistic and cultural details, the slots of the corresponding frames. For example, the frame “Pilgrimage” is supported by the lexemes “knapsack” (Bunin), “staff” (Nesmelov), “crutch” (Bozhidar).

On the periphery there are also verbs with the general semantics of loss (to lose, to forfeit, to leave), ending (to fall out of love): "Leave your home. Leave your wife and brother" (Adamovich); "You must stop loving the past. Then / The time will come to stop loving nature" (Adamovich); "It is the sweetest fate to lose everything" (Adamovich); "Like me, who lost / My Native land" (Balmont); " Only of the past forever // I have lost a dim footstep" (Rathaus).

On the periphery we see lexemes that actualize the seme 'fatigue' ("But the heart... but the heart is tired" (Adamovich), " tired of being bored, / / Tired of breathing, without strength, without money "(Adamovich)," I fall asleep in exhaustion "(Adamovich);" Our emigrant fatigue " (Kolosova).

If we make attempt to divide the semes of the conceptual component into thematic groups, it becomes clear that there are practically no lexemes that characterize the external features, the feelings and emotional states of the heroes are in the focus.

In the associative component, which includes stable associations with emigration and emigrants, the key image of a bird that cannot fly is highlighted – either its wings are damaged, or it is encaged. Thus, the "Captivity", "Prison" frames are supported. As a rule, among the bird images, the most common are pets: the parrot (for example, in the poem by Balmont) and the canary (for example, in the poem by Bunin). There is also a crane (in K. D.). Balmonta) - a migratory bird that can be in its own and other space. There is an owl with shot-through wings (Nesmelov "Owl"). These images are associated with the zoomorphic code, and the metaphors are built on the basis of several similar features – winged (in birds-wings, in people-the soul), enclosed in a cage, move from their own space to alien one, cannot voluntarily leave someone else's space, although they are burdened by being in it.

Among the key words in the associative component are "death", "darkness", and "sadness".

Associations with death are created by the lexemes "death", "dead", "die": "And slowly your dreams will die" (Adamovich); "So that only our dead years seem to be a background" (Otsup). In addition, these associations are supported by the subjective and somatic code ("Two copper coins for the ages. Crossed hands on the chest" (Adamovich) – an ancient custom to put coins on the eyes of the dead, so that the eyes remain closed; in the Orthodox tradition, it is also customary to cross the hands on the chest of the dead, so that the hands symbolize the Life-giving Cross of the Lord), a mythological code ("A dormant parka in the hands, / Where there is so little yarn left ..." (Adamovich G).

The association "darkness" is expressed by the lexemes "darkness", "obscurity", "blackness": "And there will be darkness all around" (Adamovich); " You will not dispel it// Impenetrable darkness" (Rathaus).

The association" sadness " is expressed by the synonymous lexemes" sadness"," longing"," sorrow"," grief":" What is the measure of sadness? "(Gippius);" drunk with longing "(Golenishchev-Kutuzov);" I am burning with generic longing "(Golenishchev-Kutuzov);" Sadness, like distance, grows "(Nesmelov);" These days there is so much grief "(Rathaus).

Autumn is a time of year traditionally associated with sadness, dying: "Do you hear the wind singing / In the middle of the naked branches? / The autumn sun is also getting colder, / And everything is thinner, sadder and more beautiful / The thread of my life is winding "(Kondratev); " And the trees are stricter and simpler // In the nakedness of October" (Bulich).

If autumn is the time of year when nature begins to wither, then sunset is the time of day associated with withering.

The surrounding reality, the events taking place seem so absurd that there is a feeling that everything is just a dream. This is due to the metaphor of sleep or painful delirium, expressed by the nouns "dream", "delirium", the verbs "doze", " dream»: "Let the heart sleep soundly" (Golenishchev-Kutuzov); " Oh this doom, oh this darkness / / of Meaningless sleep! "(Andreev);" My mysterious garden has dozed off "(Balmont);" Terrible, inexorable, // Irresistible delirium " (Bloch).

The evaluative component of the LCT "Russian emigrant" is dominated by negative connotations. Negative connotations are formed by the lexemes 'alien': "alien, hired house" (Bunin), "Alien will remain alien" (Severyanin); "In the land of my friends 'strangers" (Bisk); "Here the noise of foreign cities // And foreign water splashes" (Bloch), "In a foreign crowd" (Kosatkin-Rostovsky).

Conclusion

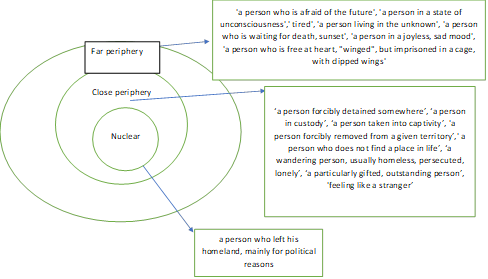

Figure 1 shows the field structure of the LKT "Russian emigrant":

The nuclear of the nominative field is the keyword "emigrant".

The near periphery is a family of occasional synonyms for this word: hostage, prisoner, captive, exile, wanderer, the chosen one.

The far periphery consists of words describing emotions (fear, sadness, longing, grief, fatigue) and words-symbols of these emotions (death, darkness, gloom, darkness, sleep, delirium, autumn, sunset, owl, parrot, canary, crane).

Acknowledgments

This paper has been supported by the RUDN University Strategic Academic Leadership Program.

References

Babushkin, A. P., & Sternin, I. A. (2018). Kognitivnaja lingvistika i semasiologija [Cognitive Linguistics abd Semasiology]. Ritm. [In Rus.]

Bobyreva, E. V., & Dmitrieva, O. A. (2018). Lingvokul'turnyj tipazh «intelligent» v zapadnoevropejskoj i russkoj kartinah mira [Linguistic and Cultural Type “Member of Intelligentsia” in Western European and Russian World Picture]. Tyumen State University Herald. Humanities Research. Humanitates, 4, 1, 29-42. DOI: 10.21684/2411-197X-2018-4-1-29-42 [In Rus.].

Bol'shoj slovar' inostrannyh slov [Big Dictionary of Foreign Words] (2003). In L.M. Suris (Ed.). Moscow: IDDK. [In Rus.] Retrieved April, 3, 2021 from https://gufo.me/dict/foreign_words

Chudinov, A. N. (1910). Slovar' inostrannyh slov, voshedshih v sostav russkogo jazyka [Dictionary of Foreign Words in the Russian Language]. Saint-Petersburg: Izdanie V. I. Gubinskogo. [In Rus.] Retrieved April, 3, 2021 from: http://rus-yaz.niv.ru/doc/foreign-words-chudinov/index.htm

Cohen, A. J. (2008). Imagining the unimaginable: World War, modern art, & the politics of public culture in Russia, 1914-1917. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Dahl, V. I. (1880). Tolkovyj slovar' zhivogo velikorusskogo jazyka [The Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language]. In 4 volumes. Saint-Petersburg-Moscow: M.O. Volf Publishing House. [In Rus.] Retrieved April, 3, 2021 from https://gufo.me/dict/dal

Dubrovskaja, E. M. (2016). Tipologija lingvokul'turnyh tipazhej: opyt sistematizacii [The Typology of Linguistic and Cultural Images: Systematization Experience]. The world of science, culture and education, 2(57), 364-366 [In Rus.].

Dubrovskaja, E. M. (2017). Lingvokul'turnyj tipazh «chelovek bogemy»: dinamicheskij aspekt [Linguistic and Cultural Type “A Person of Bohemia”: Dynamic Aspect]. Novosibirsk State Technical University [In Rus.].

Hezaveh, L. R., Abdullah, N. F. L., & Yaapar, M. S. (2014). Revitalizing Identity in Language: A Kristevan Psychoanalysis of Suddenly Last Summer. Gema Online, 14(2), 1-13. DOI:

Karasik, V. I. (2002). Jazykovoj krug: lichnost', koncepty, diskurs [Language Circle: Personality, Concepts, Discourse]. Volgograd: Peremena [In Rus.].

Karasik, V. I., & Dmitrieva, O. A. (2005). Lingvokul'turnyj tipazh: k opredeleniju ponjatija [Linguistic and Cultural Type: on the term]. Aksiologicheskaja lingvistika: lingvokul'turnye tipazhi [Axiological Linguistics: Linguistic and Cultural Types]. Paradigma, 2005. S. 5-25. [In Rus.]

Komlev, N. G. (2006). Slovar' inostrannyh slov [Dictionary of Foreign Words]. Moscow: Eksmo. [In Rus.] Retrieved April, 3, 2021 from: http://rus-yaz.niv.ru/doc/foreign-words-komlev/index.htm

Lushnikova, G. I., & Starceva, T. V. (2012). Strukturnye osobennosti lingvokul'turnogo tipazha «irlandskij jemigrant» (na materiale proizvedenija Dzh. O’Konnora «Zvezda morja») [Structural Features of the Linguistic and Cultural Image “Irish Emigrant” (on the material of J.O’Connor’s “Star of the Sea”]. Bulletin of Kemerovo State University. Philology, 18, 145-152. [In Rus.]

Lutovinova, O. V. (2009). «Lingvokul'turnyj tipazh» v rjadu smezhnyh ponjatij, ispol'zuemyh dlja issledovanija jazykovoj lichnosti [Linguistic and Cultural Type among Related Terms for Studying Language Personality]. Scholarly Notes of Transbaikal State University. Series: Philology, History, Oriental Studies, 3, 225-228. [In Rus.].

Maslova, V. A. (2018). The Main Trends and Principles of Modern Linguistics. RUDN Journal of Russian and Foreign Languages Research and Teaching, 16(2), 172—190. DOI:

Mihelson, A. D. (1866). 30000 inostrannyh slov, voshedshih v upotreblenie v russkij jazyk, s objasneniem ih kornej [30000 Foreign Words in the Russian Language with Explanation of their Stems]. Mihel’son Publishing House. [In Rus.] Retrieved April, 3, 2021 from http://elib.shpl.ru/ru/nodes/21412-mihelson-a-d-30000-inostrannyh-slov-voshedshih-v-upotreblenie-v-russkiy-yazyk-s-ob-yasneniem-ih-korney-po-slovaryam-geyze-reyfa-i-dr-m-1866

Nacional'nyj korpus russkogo jazyka [Russian National Corpus]. Retrieved April, 3, 2021 from https://studiorum-ruscorpora.ru/

Nurmoldayev, S., Orazaliyev, B., Doszhan, R., Ibragimova, T., & Kasymova, R. (2020). Cognitive analysis of intercultural communication in linguistics. XLinguae, 2, 189-196. DOI:

Schmolz, Н. (2019). The Discourse of Migration in English-language Online Newspapers: An Analysis of Images. Open Linguistics, 5(1), 421-433. DOI:

Vasileva, L. A. (2010). Lingvokul'turnyj tipazh «britanskij prem'er-ministr» (na materiale sovremennogo anglijskogo jazyka) [Linguistic and Cultural Type “The Prime-Minister of Great Britain” (on the material of modern English language)]. Nizhnij Novgorod: The Linguistics University of Nizhny Novgorod [In Rus.].

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

01 September 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-114-0

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

115

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-650

Subjects

The Russian language, methods of teaching, Russian language studies, Russian linguistic culture, Russian literature

Cite this article as:

Mikova, S. S., Inna Igorevna, R., & Luisa Nakhidovna, G. (2021). Linguistic And Cultural Type “Russian Emigrant” In Russian Émigré Literature. In V. M. Shaklein (Ed.), The Russian Language in Modern Scientific and Educational Environment, vol 115. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 316-325). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.09.35