Abstract

One of the central tasks of the Russian as a foreign language (RFL) teacher is to teach speech communication. Since the communication process is impossible without correct understanding of oral information, the issues of teaching listening skills become crucial. The listening comprehension is based on many factors and mechanisms, both linguistic and non-linguistic. Being complex and multi-stage in nature, it causes the greatest difficulties in learning a foreign language. The current study is devoted to the listening to Russian speech by Turkish students under the influence of the dominant native language (L1), and examines the difficulties caused by the linguistic factors of the second language (L2). For this purpose, an experiment was conducted, which involved 29 Turkish students of short-term Russian language courses at the initial stage of study (elementary and basic level). The experiment was complex in nature and included: a training subtest "Listening comprehension" of Test of RFL (TORFL), a questionnaire, as well as pedagogical observation, which was carried out systematically in each lesson for a month. The results of the experiment showed that crosslinguistic transfer negatively affects the process of automating the perception and recognition of Russian speech, mainly at the phonetic, morphological and syntactic levels. The theoretical results were supplemented with practical conclusions and recommendations for RFL teachers. The research materials can be used as a basis for developing a system of exercises at the initial stage of teaching listening in a Turkish audience.

Keywords: Crosslinguistic transfer, listening comprehension, linguistic difficulties, perception speech, Russian as a foreign language, Turkish students

Introduction

The intensification of Russian-Turkish cooperation in the field of trade, economy and tourism has recently generated a need for Turkish citizens to study the Russian language. Every year, new departments of the Russian language and Russian literature are opened at universities in Turkey, and Russian is also studied in short-term courses. The goals of studying Russian in courses are usually pragmatic and based on the willingness to master, first of all, the oral speech communication skills, which will allow students to successfully solve communication problems in the future when creating working contacts and conducting negotiations.

Researchers state that in order to communicate effectively, it is necessary to master the listening skill, since “there is no spoken language without listening” (Rost, 2016, p. 1). As “a key component of language acquisition” (Vandergrift & Baker, 2015, p. 391) listening comprehension plays a vital role in both the development of other language skills and the foundation of speaking ability (Namaziandost et al., 2019).

At the same time, listening is considered a very complex activity (Gilakjani & Sabouri, 2016). Indeed, the student can read or write at a convenient pace for himself, having the opportunity to refer to the dictionary, ponder the meaning of a word or thought. When speaking, the student uses only those words and speech structures that he owns. Listening is the only type of speech activity in which nothing depends on the person performing it, the listener is powerless to create more favorable conditions for himself for receiving information. From the first minutes of communication, the listener does complex mental activity aimed simultaneously at the perception of linguistic forms, understanding the content and processing information. It is not without reason that the process of such intense activity causes difficulties. Turkish students are no exception and “like many EFL students around the world, have great and persevering” problems related to listening skill. (Demirkol, 2009, p. 6).

The difficulties are largely due to the fact that listening is a multi-step process involving many factors, both linguistic and cognitive (Bloomfield et al., 2010). Linguistic knowledge is the basis for the “bottom-up processing” of L2 oral input. This way implies that the perception of the sounding utterance occurs by decoding its language elements. The second way is a “top-down processing” that involves the use of non-linguistic knowledge, such as awareness of the topic, situation, context of the message, as well as possible scenarios. The bottom-up processing “can help achieve greater success in comprehension at the beginning level of language proficiency” (Khuziakhmetov & Porchesku, 2016, p. 1999). Thus, Vafaee and Suzuki (2020) have found that vocabulary knowledge and syntactic knowledge play a ‘significant role’ in L2 listening ability (p. 21). Buck states that the most important types of linguistic knowledge that involved at listening comprehension’s work are “phonology, lexis, syntax, semantics and discourse structure” (Buck, 2001, p. 2). Bang and Hiver (2016) confirmed empirically that grammar and vocabulary knowledge are “key factors in determining L2 listening proficiency that may at certain levels even override other cognitive and affective factors” (p. 17).

It is important to note that it is not just knowledge but skills formed on the basis of knowledge are crucial in the listening comprehension. A listening skill is “a speech operation brought to the level of automatism and associated with recognizing and distinguishing individual sounds and sound complexes orally” (Azimov & Shchukin, 2009, p. 25). If listening is not automatic, then comprehension suffers (Joaquin, 2018).

It is formed i.e., brought to automatism listening skills, including hearing-pronouncing and receptive lexical-grammatical skills (Kolesnikova & Dolgina, 2008, p. 186), that provides rapid comprehension and is an important criterion for the listening process, since logical processes must be carried out in the limited time.

Significant barriers to the formation of these skills are the complexity of perception of language input, which is primarily explained by the interference of the native language in the process of speech perception L2. Cutler (2000) argues that “listeners' expectations of how meaning is expressed in words and sentences are shaped by the vocabulary and grammar of the native language; but phonology plays an even more direct role” (p. 1). Shutova and Orekhova (2018), speaking of the phonetic aspect, note that “when starting to learn a foreign language, students have stable listening and pronunciation skills of their native language <…> which are transferred to the foreign language” (p. 262). Darcy et al. (2015) state that the phonological knowledge using “cannot easily be inhibited when processing L2 input” (p. 63).

The multilingual transfer can involve various aspects of language, and its negative effect is the stronger the greater the difference in these aspects between the native and foreign languages. Since Russian and Turkish belong to distinct language families, Turkish is an agglutinative language, Russian is a fusional one, the presence of linguistic features in the Russian that are specific to Turkish students and different from their native language gives rise to difficulties in listening comprehension L2.

Native language effect when teaching a foreign language is one of the main linguodidactics principles of the Russian methodological school. Researchers conduct comparative studies of L1 and L2, study the specificity of teaching Russian in different national audiences, for example, in Korean (Deponyan, 2016), in Thai (Sakkornoi, 2016), in Arabic (Strelchuk & Ermolaeva, 2019). However, teaching listening skills to Turkish students is the least developed section of the RFL methodology.

Problem Statement

Since, in the light of the communicative-activity approach adopted in the RFL methodology, the main task of teaching Russian language is the practical-oriented language proficiency, teaching listening skills, regardless of the type of educational institution, becomes crucial.

Without the ability to understand oral speech, the formation of communicative competence is impossible. The grounding of speech skills occurs at the initial stage of language learning, it is at this stage that it is important to teach students how to correctly perceive a sounding message.

In the absence of a language environment and a limited number of practical lessons, this task can be extremely difficult. In this regard, the teacher needs to take into account the native language effect on the listening comprehension and the difficulties caused by the negative transfer of linguistic features L1 to L2, which will allow to direct pedagogical attention to overcoming these difficulties, and in general, to intensify the process of teaching RFL.

However, to this date, we are not aware of the existence of studies on the topic of listening comprehension of Russian speech by Turkish students. This article is therefore particularly relevant.

Research Questions

The study elucidates the following questions:

- What kind of linguistic difficulties do Turkish learners face in listening at the initial stage of Russian language learning?

- What is the relationship between the listening ability and the linguistic features of L1 and L2?

- Is the nature of linguistic difficulties in listening changing? (if the А1→А2 level changes)

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study is to examine and analyze the peculiarities of the perception and recognition of Russian speech by Turkish students in the context of multilingual transfer at the initial stage of RFL learning outside the linguistic environment and to provide recommendations to RFL teachers that can be used in organizing teaching listening skills in a Turkish audience.

To achieve the purpose, the article discusses the following issues: identification of linguistic factors affecting the listening, and their analysis based on a comparison of two language systems.

Research Methods

The experiment was carried out in August 2020 on the base of language courses in Istanbul. The courses are designed for 9 months of RFL learning with 9 academic hours per week under the guidance of a teacher and 3 hours of independent work to consolidate the learned material. The participants of the experiment were students of the 3rd (N=15) and 6th (N=14) months of study. The age of the participants is 22-37 years old. The experiment was complex in order to obtain the most objective data and included the following forms of control over the listening of Russian speech:

Training subtest “Listening comprehension” of TORFL

In order to determine the level of compliance with the mandatory requirements for speech skills, the participants were asked to pass the Listening subtest based on typical tests in RFL, offered by the TORFL GO mobile training application. The application was developed in 2018 by the International Association of Teachers of Russian Language and Literature (MAPRYAL) and is used to prepare for TORFL. In the Russian system of proficiency levels, there are 6 levels: elementary, basic, first, second, third, and fourth, which correspond to the levels A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, and A6 of the European system. Students of the 3rd month of study were tested at the elementary level (A1), students of the 6th month-at the basic level (A2).

In order to focus on the linguistic difficulties and remove non-linguistic ones, such as a rapid speech tempo, a large number of unfamiliar words, long audiotext time, too long sentence (more than 10 words), testing was carried out on inauthentic audiotexts, that is, specially created on the basis of lexical and grammatical material corresponding to the level of language proficiency.

Various types of audiotexts were used, such as short audio messages, micro-dialogs, dialogues, monologues recorded by Russian native speakers. The subject of the text is relevant for everyday and sociocultural spheres of communication. The audiotexts are based on the lexical minimum, which is 780 words at the elementary level, and about 1300 words at the basic level (Andryshina & Kozlova, 2016). The duration of the longest audiotext did not exceed 105 seconds for A1 level and 130 seconds for A2 level. The speech tempo was measured in syllables and was no more than 130 syllables per minute for texts for level A1 and no more than 200 syllables per minute for A2. The speech tempo included natural pauses. The subtest consisted of 20 tasks that were asked to complete during listening. The test-takers had to choose the correct answer from the three proposed options. Audiotexts were presented for listening 2 times. The execution time was 30 minutes. The test-takers were instructed in detail on the completion and structure of the test forms.

Questionnaire

After completing the subtest, students were offered an anonymous questionnaire to understand the depth of understanding of difficulties during listening. The questionnaire consisted of two parts and was written in Turkish. In the first part, participants were asked to rank linguistic difficulties on a 5-point Likert scale (from 5-very difficult to 1-easy):

- “I find it difficult to correctly perceive sounds, sound combinations, intonation” (Phonetic difficulties).

- “I find it difficult to understand the meaning of words” (Lexical difficulties)

- “I find it difficult to understand the forms of word changes in oral speech” (Morphological difficulties).

- “It is difficult for me to understand the structure of the sentence, the ways of combining words in oral speech” (Syntactic difficulties).

The second part of the questionnaire contained one open-ended question: “It is easy / difficult for me to perceive and recognize Russian speech, because ...”. A total of 29 responses were received in Turkish and analyzed.

Lesson observation

Lesson, or pedagogical, observation of the students’ learning activities was carried out during the lessons, as well as watching the videos of the lessons. The observation was conducted systematically at each lesson in accordance with the plan for teaching listening skills during the following practice items and exercises:

- Sounds perception and recognition

- Intonation pattern of a sentence and syntagm determination

- Imitative repetition of words, word combinations, phrases, sentences

- Word separation into syllables, sounds

- Hard and soft consonants; voiced and voiceless consonants differentiation

- Phonetic dictations

- Word stress and vowel reduction recognition

- Grammatical forms identification

- Words order in sentence determination

- The results were recorded as facts in the observation diary, compared with other research methods and complemented each other.

Findings

As a result of training testing, the following data were obtained, presented in table 1.

Analysis of the obtained test data allows us to draw the following conclusions:

- None of the test-takers achieved a complete (100%) comprehension of audiotexts.

- Students in the 3rd month of study performed better in listening comprehension than students in the 6th in the average.

- Four students from the group in the 6th month of study did not score the required minimum to pass the test for level A2 - 66%, while gaining 42%, 59%, 64%, 65%.

- In general, the average rates are satisfactory, but they demonstrate the presence of difficulties in listening comprehension of Russian speech.

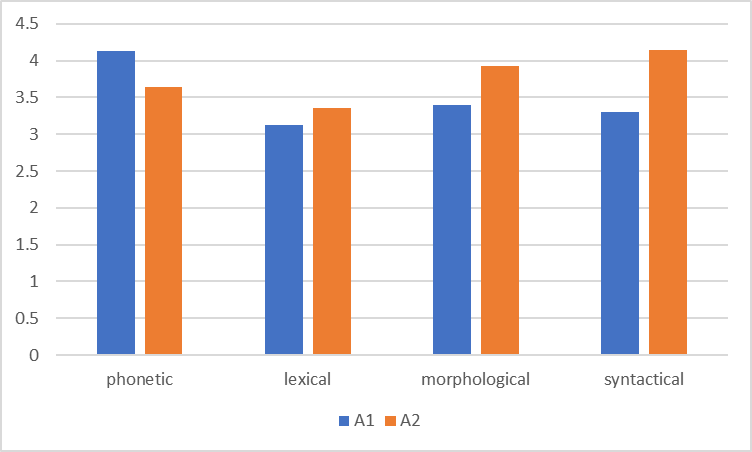

The answers of the first part of the questionnaire were given to the arithmetic average, and as a result, the complexity of the linguistic factor was distributed as follows and is presented in Figure 1.

The data obtained indicate that:

- In both groups, students have significant linguistic difficulties in listening.

- At the A1-level, phonetic difficulties predominate. At the very beginning of language learning, phonematic hearing is just beginning to develop.

- At the A2-level, lexical and grammatical difficulties come to the fore. At this stage of learning, the breadth and depth of the vocabulary, syntactic material, in comparison with its relative simplicity at the A1-level, occurs.

With lacking automaticity of lexical and grammatical skills, difficulties in listening comprehension are aggravated. Apparently, this may explain the poorer results when performing the "Listening" subtest by A2-level students.

The written responses to the second part of the questionnaire, in general, clarify the results of the assessment of the complexity of the close-ended questions. To the open-ended question “It was easy / difficult for me to understand Russian speech, because ...” the most frequent answers were: “I do not recognize familiar words in speech”, “Words run together in speech and sound differently”, “I recognize single words, but I don’t understand the meaning of the phrases”, “While I think about grammar, I skip the next part of the message”. Total 23 answers out of 29 (% 79.3) related to the difficulties of recognizing phonetic, grammatical characteristics of familiar linguistic material in a new context.

From the results of lesson observation and study of mistakes during the exercises, a number of difficulties were identified, which were analyzed and grouped:

Phonetic difficulties

The formation of phonetic skills, by which we mean the reception and recognition of the studied phonemes, words stress and intonation in the speech flow, is complicated by the multilingual transfer. In 1939, Trubetskoy (1960) noted that listeners used their native phonology as a “sieve” to perceive L2 sounds (p. 54). The appearance of dissimilar sounds in L2 speech to sounds in L1 was identified as one of the main difficulties arising in the process of listening to English audiotexts by Turkish students (Yıldırım, 2013).

For example, the absence of the voiceless affricate [ц] [ts] in Turkish makes it difficult to distinguish between the phonemes [ц] [ts] and [c] [s], they are not recognized in the oral speech. The phrase «В следующем месяце мы пойдем в цирк» (“Next month we will go to the circus”) caused difficulties in listening, because there are two phonemes at once that are absent in the Turkish language - [ц] and [щ] [ᶋi:]. Even such frequent words as “цифра” (“digit”), “танцевать” (“dance”) sometimes cause an over-asking in the audience in order to clarify the meaning, while when repeating, an intermediary sound is used: [s'ifra], [tans'evat].

Indeed, the sounds spoken by a native speaker are different from how L2 learners pronounce them. During listening, students can often be seen trying to repeat what they hear in order to recognize and decode familiar words. That is, during listening, the articulatory organs are active. The clearer L2 articulation, the more successful the listening process is, since we perceive correctly only those sounds that we can reproduce.

The formation of L2 articulation is hindered by various specific features of the phonetic system of L1. For example, in Turkish, the factor that determines many phonetic and morphological processes is vowel harmony. There are two types of harmony. The first type of harmony assumes that if the native Turkish word begins with a syllable containing velar vowel (a, ı, o, u), then all other syllables should contain only a velar vowel (e.g., ayakkabı (shoe), çocuk (child), if the first syllable contains palatized vowel (e, i, ö, ü), then all subsequent syllables should also be palatized (e.g., çiçek (flower), köpek (dog). The second law of harmony is that when building up affixes to a word, only labial vowel (o, u, ö, ü) of the last syllable can be followed by labial vowel (e.g., okulum (my school), and non-labial (a, ü, e, i) – non-labial, respectively (e.g., öğretmenin (your teacher). In addition, palatized vowel affects the pronunciation of consonants in a word, they soften not only before vowels, but also after them (e.g., ekmek [ek'm'ek’] - bread vs. kol [kol]- arm).

Turkish listeners unconsciously transfer the laws of harmony to Russian, which is characterized by its various co-occurrence of hard and soft consonants within a single word. And, as a result, this leads to phonological nondistinction of phonemes such as [l] [l’], [k] [k’], [t] [t’], etc., which makes it difficult to determine the semantics of words in the speech flow (e.g., есть [yest’] be present, ест [yest] eats].

Given these features of the L1 articulation, it is necessary to form student's clear and stable pronunciation skills and carry out systematic work to improve the quality of pronunciation.

The most significant reason for not recognizing familiar words in the speech flow is the qualitative vowels reduction in Russian. It changes the sound characteristics. There is no such language feature in Turkish, vowels retain their qualitative characteristics in all positions. Under the influence of interference, the same way Turkish students pronounce Russian words, that is, without taking into account the phonological change of Russian vowels.

The issue of vowel reduction is closely related to the issue of word stress, since unstressed vowels are reduced. The word stress systems in the Russian and Turkish languages are substantially different. In Russian, word stress is strongly-centralizing, “stressed and unstressed syllables differ in different prosodic parameters: duration, intensity, and frequency of the main tone” (Chalykova, 2016, p. 110). In Turkish, the stress is weakly-centralizing and does not cause changes in the vocalism of the word. In addition, in Turkish, the stress is fixed, in most cases it is on the last syllable of a word. On the contrary, in Russian, the stress is free, which means it can be on any syllable (e.g., ру́чка (pen), тетра́дь (notebook), каранда́ш (pencil) and movable, which means it can be transferred from one syllable after another in the formation of the plural (e.g., го́род [go:rᴧt], города́ [gᴧrᴧdᴧ:] (cities), new grammatical forms (e.g., рука́, ру́ку (arm), etc.

The orthography of the Russian language does not in any way indicate the vowel reduction in an unstressed position (e.g., молоко́ [mᴧlᴧko] milk, отец [ᴧt’ets] father). This means that having a stronger graphic standard of a word in memory than a phonetic one, a student can make perceptual mistakes.

Difficulties in forming graphic-phonemic connections are caused by the discrepancy between the orthography systems in Turkish and Russian. Turkish language is characterized by a phonetic spelling principle (words are written in the same way as they are heard).

For this reason, introducing new words follows this order: listening→ repeating → writing → reading.

Morphological difficulties

The morphological structures of the Russian and Turkish words have significant differences. Russian belongs to the group of fusion languages, while Turkish belongs to the group of agglutinative languages. Grammatical meanings in Turkish are usually conveyed by affixes that are sequentially added to the word. Reformatsky (1955) compared the word built according to the principle of agglutination with "a long train, where the root is a locomotive, and the chain of affixes is rail cars, the "gaps" between which are always clearly visible" (p. 214). For example, arkadaşlarımla (with my friends) decomposes into arkadaş (friend) + -lar (many) + -ım (my) + -la (with). The root of the Turkish word always remains unchanged, and the affixes are unambiguous, which means that each grammatical category is expressed by one affix (e.g., şeker (sugar) + siz = şekersiz (without sugar).

In Russian, affixes, or morphemes, are prefixes, suffixes, flexions, and postfixes that are attached to the root and used for the formation of a new words or their grammatical forms. At the morphemic boundary, changes can occur, for example, interchange of sounds, as a result of which morphemes can change their original characteristics (e.g., (sb.) снег (snow) + suffix -н + flexion -ый = (adj.) снежный; (sb.) река - (adj.) речной (river); (verb) бежать – бегу (run), плыть – плыву (swim), печь – пеку (bake) etc.). Such interchange of phonemes during listening makes it extremely difficult to determine the semantics of a word in an analytical way, which is familiar to Turkish students.

It is also important to note that in Turkish there are no prepositions or particles in front of the word root, unlike Russian. For comparison: в музее – müzede (in the museum), не говори – söyleme (do no say). In addition, in Russian, the root can be combined with prefixes, forming a new meaning of the word. For example, писать (write) – записать (make a note), переписать (rewrite), приписать (ascribe).

The grammatical features, unfamiliar to the Turkish language, lead to the fact that in the speech flow the Turkish listeners have difficulties in catching and separating speech units and their elements. Most often this is affected either in the fused perception of prepositions and words, or in the separate perception of parts of one word.

Such a defect in the analysis and synthesis of oral speech is detected when writing. For instance, in the student’s phonetic dictations, the following deviances of the word’s differentiation can be found: the fusion of the preposition and word - «мясо саваща ми» - мясо с овощами (meat&vegetables), «варту» - во рту (in a mouth), «пастарана» - по сторонам (on both sides); the separation of the prefix from the root: «раз смотрел» - рассмотрел (descry), «пос спешить» - поспешить (to hurry). The lack of Russian word-formation awareness complicates the listening comprehension, hinders the process of contextual guess, which prompts the lexical meaning of a word by its structure.

To prevent such mistakes, good results have been obtained by using the method of introducing new words with the highlighting of prefixes, roots and suffixes in it, as well as introducing new words with the most common prepositions.

Syntactical difficulties

Along with morphology and phonetics, syntax plays an important role in listening. It is the syntax that determines the words combining laws of in the speech flow.

Almost half of A1-listeners found it difficult to find a predicate in the utterance «Бизнесмен проводит встречи с партнёрами в Стамбуле каждый месяц» (A businessman meets with partners in Istanbul every month). Difficulties in identifying the principal parts of the sentence lead to a misunderstanding of its meaning.

The reason for the difficulties lies in the fact that, unlike Russian, the word order in the Turkish sentence is quite fixed, namely, the predicate verb with a personal predicative affix takes the last position. The most important word in meaning is located directly in front of it (e.g., Tarkan dün sizi görmüş (Tarkan yesterday you saw)/ Dün size tiyatroda görmüş) (Yesterday you at the theatre saw)/ Tarkan dün tiyatroda görmüş (Tarkan yesterday at the theatre saw). Unconsciously directing the main attention during listening to the end of the sentence, as the most informational-significant part, Turkish listeners miss the general meaning of the Russian sentence, the word order in which is relatively free and depends on the speaker's intentions.

Russian oral speech is mainly formed as follows, first - what is happening and with whom, and then - details, secondary parts of the sentence. Thus, the Russian phrase is difficult perceptible for Turkish listeners, since it is built according to a model that differs from the one used in their native language. Russian utterance listening requires additional cogitative operations to transform it to the L1-model (for comparison: Her ay Istanbul’da iş adamı ortaklarıyla buluşuyor/ «Каждый месяц в Стамбуле бизнесмен с партнёрами проводит встречи»).

This process certainly slows down the speech reception. Therefore, increased attention should be paid to the formation of L2 phrase construction skills.

It should be added that significant barriers to the listening comprehension at the initial stage are also created by grammatical features that are characteristic only for L2, such as, the category of gender, three types of declension, verbal aspect. Trying to identify them, listeners do not perceive the content of oral speech, which is irreversible in nature.

Conclusion

The results of the study showed that listening to Russian speech causes significant linguistic difficulties for Turkish students at the initial stage, with a predominance of phonetic difficulties at the elementary level and grammatical difficulties at the basic one.

The difficulties are caused by the multilingual transfer and are associated with the presence in the Russian language of the following linguistic features that are unusual and unfamiliar for Turkish listeners:

- qualitative vowels reduction;

- free and movable word stress;

- lack of sound harmony laws;

- sound interchange at the morphemic boundary;

- complex orthography system;

- prefixes and prepositions using;

- free word order in the oral sentence.

To anticipate and remove these difficulties, it is recommended to pay attention to working on phonetics, morphology and syntax in the following directions when teaching listening:

- hearing and pronunciation skills formation (recognition of sounds and training in their pronunciation, definition of a stressed vowel);

- speech flow differentiation (determination of the number of syllables in a word, words in a syntagma; boundaries between syntagmas);

- word morphemic structure analysis (definition of prefix, root, suffix, flexion);

- of sentence syntactic models’ analysis (definition of an object, subject and predicate).

- The automaticity of the phonetic and lexical-grammatical skills necessary for successful listening can be facilitated by a conscious teaching method based on a comparative analysis of two languages and contrastive exercises.

The research perspective is the developing of a methodological system aimed at overcoming the Turkish students’ listening comprehension difficulties in Russian language learning in the initial stage, which will intensify the process of teaching listening skills.

Acknowledgments

This paper has been supported by the RUDN University Strategic Academic Leadership Program

References

Andryshina, N. P., & Kozlova, T. V. (2016). Leksicheskiy minimum po russkomu yaziku kak inostrannomu. Bazoviy uroven. Obshchee vladenie [Lexical minimum of Russian as a foreign language. Basic Level. Common language]. Zlatoust. [in Rus.].

Azimov, E. G., & Shchukin, A. N. (2009). Noviy slovar metodicheskih terminov i ponyatii (Teoriya i praktika obucheniya yazikam) [New Dictionary of Methodical Terms and Definitions (Theory and Practice of Language Teaching)]. IKAR Publisher. [In Rus.].

Bang, S., & Hiver, P. (2016). Investigating the structural relationships of cognitive and affective domains for L2 listening. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 1(7), 1-19. DOI:

Bloomfield, A., Wayland, S. C., Rhoades, E., Blodgett, A., Linck, J., & Ross, S. (2010). What makes listening difficult? Factors affecting second language listening comprehension. University of Maryland Center for Advanced Study of Language, College Park, MD.

Buck, G. (2001). Assessing listening. Cambridge University Press. DOI:

Chalykova, T. I. (2016). Osnovi phoneticheskoi interferentsii pri obuchenii russkomu proiznosheniu nositeley turetskogo yazika (na materiale glasnih) [Phonetic interference basis when Teaching Russian Pronunciation to Native Turkish Speakers (on the material of the vowels)]. Didactic Philology, 3, 103-113. [in Rus.].

Cutler, A. (2000). Listening to a Second Language through the Ears of a First. Interpreting, 5(1), 1-23. DOI:

Darcy, I., Park, H., & Yang, C. L. (2015). Individual differences in L2 acquisition of English phonology: The relation between cognitive abilities and phonological processing. Learning and Individual Differences, 40, 63-72. DOI:

Demirkol, T. (2009). An investigation of Turkish preparatory class students listening comprehension problems and perceptual learning styles. [Unpublished master’s thesis], Bilkent University, Ankara. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/11693/15454

Deponyan, K. A. (2016). Natsional'no orientirovannyi podkhod k obucheniyu russkomu yazyku kak inostrannomu v respublike Koreya (na materiale russkoi antroponimicheskoi sistemy) [National-oriented approach in teaching Russian as a foreign language in the Republic of Korea (based on the Russian anthroponymic system)] [Author’s abstr. cand. ped. diss.]. Moscow. [In Rus.].

Gilakjani, A. P., & Sabouri, N. B. (2016). Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review, English Language Teaching, 9(6), 123-133. DOI:

Joaquin, A. (2018). Automaticity in Listening (in TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching, Wiley-Blackwell Publishers). TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching. DOI:

Khuziakhmetov, A. N., & Porchesku, G. V. (2016). Teaching Listening Comprehension: Bottom-Up Approach. International journal of environmental & science education, 11(8),1989-2001. DOI:

Kolesnikova, I. L., & Dolgina, O. A. (2008). Anglo-russkiy terminologicheskiy spravochnik po metodike prepodavaniya inostrannih yazikov [A Handbook of English-Russian Terminology for Language Teaching]. Cambridge University Press and Drofa Publishers [in Rus.]: Moscow.

Namaziandost, E., Neisi, L., Mahdavirad, F., & Nasri, M. (2019). The relationship between listening comprehension problems and strategy usage among advance EFL learners, Cogent Psychology, 6(1), 1691338. DOI:

Reformatsky, A. A. (1955). Vvedenie v yazikoznanie [Introduction to linguistics]. Moscow [in Rus.].

Rost, M. (2016). Teaching and Researching Listening (3rd edition). Routledge.

Sakkornoi, K. (2016). Natsional'no-orientirovannaya model' obucheniya taiskikh uchashchikhsya russkomu yazyku (bazovyi uroven') [National-oriented model of teaching Thai student’s Russian language (basic level)] [Author’s abstr. cand. ped. diss.]. Saint Petersburg. [In Russ.].

Shutova, M. N., & Orekhova, I. A. (2018). Phonetics in Teaching Russian as a Foreign Language. Russian language studies, 16(3), pp. 261—278. DOI:

Strelchuk, E., & Ermolaeva, S. (2019). Teaching online Russian language as a foreign through Social Networks (inicial stage). 12th Annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation (ICERI): Seville, SPAIN, nov. 11-13, 2019: ICERI Proceedings, pp. 1970-1975. https://doi.org/10.21125/iceri.2019.0554

Trubetskoy, N. S. (1960). Osnovi phonologii. [Phonology basics]. Moscow. [in Rus.]

Vafaee, P., & Suzuki Y. (2020). The relative significance of syntactic knowledge and vocabulary knowledge in second language listening ability. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 42(2), 383-410. DOI:

Vandergrift, L., & Baker, S. (2015). Learner Variables in Second Language Listening Comprehension: An Exploratory Path Analysis. Language Learning, 65(2), 390–416. DOI:

Yıldırım, S. (2013). A comparison of EFL teachers’ and students’ perceptions of listening comprehension problems and teachers’ reported classroom practices. Unpublished MA thesis. Bilkent University, Ankara. http://repository.bilkent.edu.tr/handle/11693/15663

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

01 September 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-114-0

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

115

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-650

Subjects

The Russian language, methods of teaching, Russian language studies, Russian linguistic culture, Russian literature

Cite this article as:

Ryabokoneva, O. (2021). Turkish Students’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties In Russian Language Learning. In V. M. Shaklein (Ed.), The Russian Language in Modern Scientific and Educational Environment, vol 115. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 129-140). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.09.15