Abstract

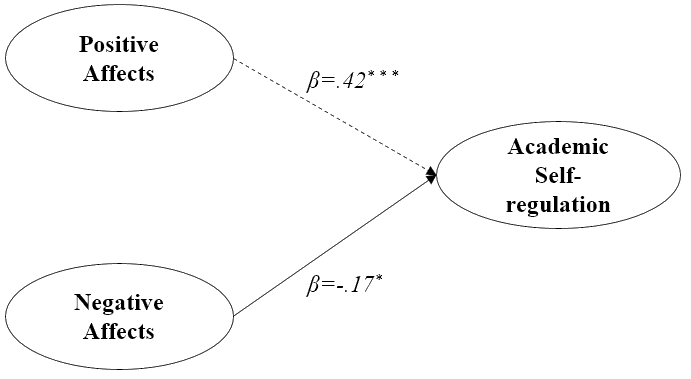

The positive and negative affects influence print or negatively in future initial education teachers. For these motives the target of the present investigation was to analyze the levels of positive affections (AP) and negatives (AN), and its influence in the academic self-regulation. The sample was of 148 students (100% women) between 16 and 52 years old (Mage = 26.20, SD = 6.53) of the first one to the third studies cycle of the initial education career of a university private of Lima – Peru. The results demonstrated the predominance of the positive affections in contrast to the negatives. And the analyses of multiple linear retrogressions demonstrated that the positive affections predict to the suitable academic self-regulation (β =.42, p <.001), and to the ideal academic performance (β =.20, p <.01). But the negative affections predict the inadequate academic self-regulation this being the interest of study in early education students (β =-.17, p <.05).

Keywords: Initial education careernegative affectspositive affects

Introduction

The recent conceptualizations of emotions refer to these as manifestations or emotional experiences that are molded socially and that depend on the environment (Stanley, 2017); thus, in this context in which people live, they can express their positive affections (PA) (enthusiasm, engagement, pleasure or concentration), ambiguous affections or negative affections (NA) (dislike, anger, contempt, fear or anxiety) (Gray & Watson, 2007). These affective polarities (positive affect PA and negative affect NA) are significantly related to psychological well-being, mental health (Alkhalaf, 2018), the degree of psychological balance and satisfaction with the life that each person experiments; being also of vital importance in future teachers (Gonzáles et al., 2017). Workers who upon graduation and being in the exercise of their career have been considered as the professionals with the highest levels of stress since the 90s of the last century (Pithers & Fogarty, 1995) and in the first decade of this century (Extremera et al., 2010) due to the excessive workload and low salary, which end up exhausting him (a) physically and mentally (Castillo & Montero, 2010). On a physical and mental level, teachers experiment fatigue, irritability, anxiety, depression, stress, burnout, absenteeism (Prieto & Bermejo, 2006), demotivation (Silvero, 2007), heart problems, poor empathy with the student and planning of their learning sessions (Burke et al., 1996).

It is known that PAs have positive effects on well-being and academic performance (Gonzáles et al., 2017), and ANs such as anxiety or stress negatively affect the overall functioning of students (Alkhalaf, 2018), being important to investigate in university students in education careers. For example, the importance of PA and NA in future teachers could be confirmed in the empirical studies of Gonzales, Gonzales and San José in which in a sample of 143university students of the initial and elementary education careers. In this study identified that the PA were significantly related to adequate academic achievement, optimal mental health and adequate levels of life satisfaction (psychological well-being). Then it was identified that the NA are negatively related to mental health and life satisfaction; evidencing that NA are associated with mental problems and dissatisfaction, frustration or discomfort with life.

Finally, concluding that the PA and NA allowed predicting the mental health of future teachers of initial and primary education. Even in this study it was identified that in the students of the professional career of initial education there was a greater predominance of positive affects than in the students of the professional career of primary education (Gonzáles et al., 2017). These studies are essential because they allow us to observe how the emotional state of teachers and teachers could express some kind of positive or negative affect that affects their well-being and mental health (Alkhalaf, 2018), having as harmful consequences for themselves and their work, educational, affecting their relations with the student (Burke et al., 1996). Of course, taking into account that the relations between the teacher and the students are the essence of the teaching and learning processes (Brinkworth et al., 2018). Being these, the reasons why it is relevant to study the expressions of the PA and the NA in students of the education career in the Peruvian context. In addition, while it is known in Peru, secondary school teachers are the teachers with the greatest emotional distress (Marenco-Escuderos & Ávila-Toscano, 2016), in this study we want to explore the levels of PA and NA in students of the professional career of initial education, who are predominantly of the female sex (Consejo Nacional de Educación, 2014). Moreover, with greater reason, because the female teaching population is more prone to psychiatric problems at the time of exercising the professional career (Bermejo-Toro & Prieto-Ursúa, 2014).

Problem Statement

-

In the Peruvian context, there is a great demand for initial education teachers and at the same time there is a demand to train initial education teachers with a suitable psychological and emotional profile to practice the profession (Consejo Nacional de Educación, 2014). For these reasons, it is essential to carry out a diagnosis of PA and NA (Gray & Watson, 2007) in future teachers.

Research Questions

What are the levels of positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) in students of the professional career of initial education of a private university in Lima-Peru?

Purpose of the Study

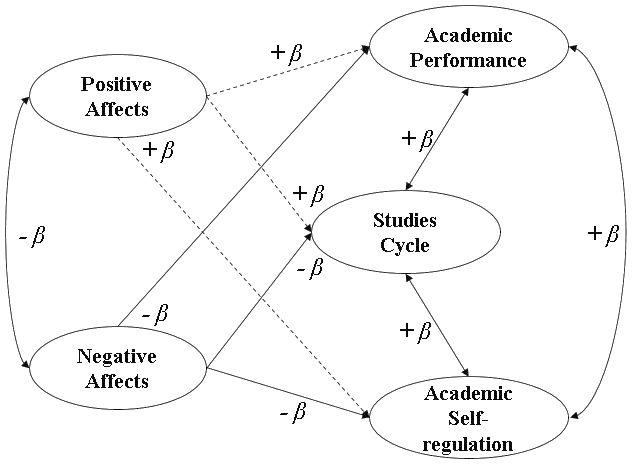

According to the above, the objective of this research is to analyze the levels of positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) in a sample of students of the professional career of initial education of a private university in Lima-Peru, view figure

Additionally, the following hypotheses are proposed:

The positive affect (PA) positively predicts to academic performance, studies cycles and academic self-regulation, and,

The negative affect (NA) negatively predicts to academic performance, studies cycles and academic self-regulation.

Research Methods

In accordance with the hypotheses, the present study proposes a quantitative methodology (Appelbaum et al., 2018).

Participants

The sample was of 148 students (100% women) between 16 and 52 years old (Mage = 26.20, SD = 6.53) of the first one to the third studies cycle of the initial education career of a university private of Lima – Peru.

Measures

Scale of Positive and Negative Affect Schedule of López-Gómez et al. (2015). This scale evaluates the two polarities of the affects, the AP and the AN. It consists of 20 items, with 5 response dimensions on the Likert scale. In the present study, the adaptation to the Peruvian context was performed, finally obtaining an abbreviated version of 15 items; of which 7 items correspond to AP and 8 to AN. This version thus maintains the two-dimensionality of the original scale (Thompson, 2007). In present study, we obtained adequate evidence of validity (KMO = .71) and the Bartlett Sphericity Test was significant (χ² = 395, 428, gl = 105, p <.001). Cronbach's alpha internal consistency coefficient was .66 for the positive affects subscale, and .78 for negative affects subscale; demonstrating to be reliable (Aiken, 2002).

Findings

Analysed the psychometric properties (validity and reliability) was analyzed results in the following order:

Comparison of means

Table

Boxplots Analysis

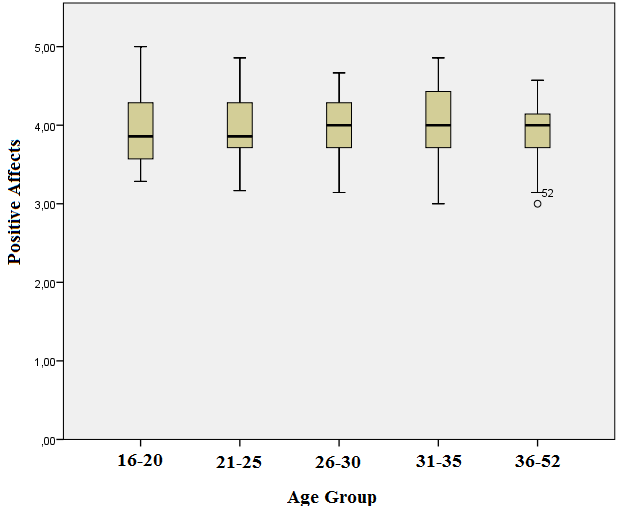

To identify more particular cases in this boxes analysis (Boxplots) (Helsel, 2011) X deposited in the axis variable age group and in the axis Y the variable frequency of positive affects (figure

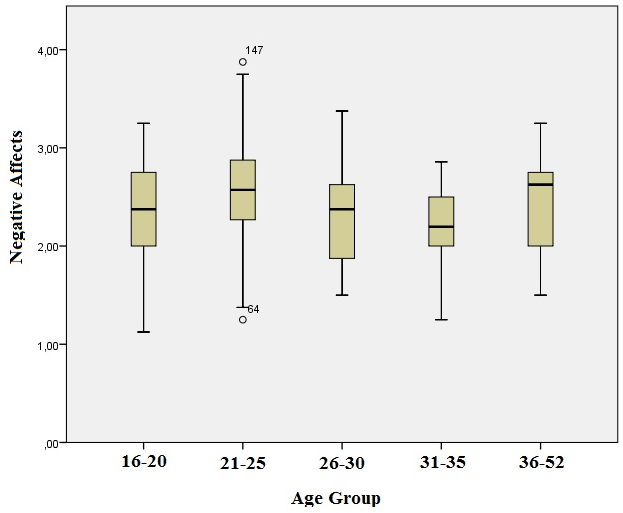

Then, next boxes analysis (Boxplots) (Helsel, 2011) X deposited in the axis variable age group and in the axis Y the variable frequency of negative affects (figure

Relation between variables

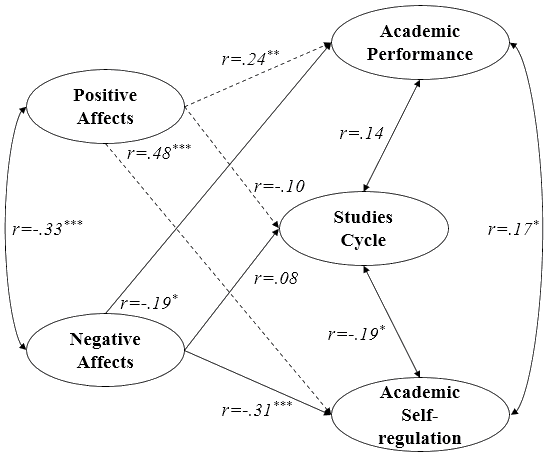

Then, analyzing relationships between variables it was made by Pearson's r correlation coefficients and evaluated with criteria Cohen (1992) for Social Sciences (

Also, the variable “studies cycle” demonstrated a light negative relationship with the “academic self-regulation” (

Multiple linear regression

Identifying significant relationships linear regression analysis was performed to estimate the predictive value among the variables studied (Bingham & Fry, 2010). Thus, in figure

This finding allows to observe that the positive affections (enthusiasm, engagement, pleasure, or concentration) of the students of the initial education career will allow them the adequate and responsible organization of the educational activities. But on the contrary, negative affects (dislike, anger, contempt, fear or anxiety) will negatively influence the academic organization of students.

Conclusion

Discussion

The objective of this research was to analyze the levels of positive affect (PA), negative affect (NA) and its influence on academic self-regulation in students of the professional career of initial education of a private university in Lima-Peru. And according to the same analysis, it was possible to identify that the median of the positive affects was higher than the negative ones. This allowed to conclude and confirm the studies of Gonzales, Gonzales and San José; who reported that positive affections predominate in students of the initial education career (Gonzáles et al., 2017).

In addition, the main analyzes using the linear regressions allowed us to identify the predictive power of the positive affect variable anticipates academic self-regulation. In other words, in the students of the initial education career, experiencing affects such as mood, dedication, commitment, or enjoyment in their daily lives will allow the future to self-control their educational tasks responsibly (Gonzáles et al., 2017). But the experiences of negative affects (such as envy, distrust, dislike, anger or fear) are detrimental to their educational work, having unfavorable consequences in the future such as academic disorganization (Alkhalaf, 2018).

And finally, regarding positive affects, it was possible to identify that their experience positively predicts academic performance. This means that experiencing positive affects such as trust, pleasure, engagement, etc. It will have favorable consequences on their academic achievement in their studies, expressed in better grades (Gonzáles et al., 2017).

Conclusions and future works

At the end of this study, it is concluded that positive affections predominate in the students of the professional career of initial education, and these affections express them with their good mood, with enthusiasm, engagement, concentration and enjoyment. But, the presence of negative affects expressed with behaviors of rejection, anxiety, fear, anger, displeasure or contempt has been observed. In addition, the findings allow to anticipate that positive affects influence and influence academic self-regulation and academic performance; but negative affects turn out to be detrimental to academic self-regulation.

These results will allow the development of future strategies for the investigation of the reasons why negative affections continue to manifest in order to carry out psycho-pedagogical interventions or tutorials with the students. Thus, the future steps will be to carry out tutoring and educational guidance actions to promote and reinforce positive affects in students, and at the same time, to prevent and apply remedial measures in the face of the expression of negative affects. Being the most worrying about the negative consequences in teachers such as depression, burnout (Prieto & Bermejo, 2006), work demotivation (Silvero, 2007), misunderstanding with the student or improvisation of learning sessions (Burke et al., 1996).

Acknowledgments

The present investigation has been developed thanks to the constant support of Andrea Liberata Blas, Maximiliano Bravo and Martha Cunza.

References

- Aiken, R. (2002). Psychological testing and assessment (11th Ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Ahsnullah, M., Kibria, G., & Shakil, M. (2014). Normal and Student´s T distributions and their applications. Atlantic Press.

- Alkhalaf, A. (2018). Positive and negative affect, anxiety, and academic achievement among medical students in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience, 20(2), 397.

- Appelbaum, M., Cooper, H., Kline, R., Mayo-Wilson, E., Nezu, A., & Rao, S. (2018). Journal Article Reporting Standards for Quantitative Research in Psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board Task Force Report. American Psychological Association, 73(1), 3 – 25.

- Bermejo-Toro, L., & Prieto-Ursúa, M. (2014). Absenteeism, burnout and symptomatology of teacher stress: sex differences. International Journal of Educational Psychology, 3(2), 175-201.

- Bingham, N., & Fry, J. (2010). Regression: Linear models in statistics. Springer.

- Brinkworth, M., McIntyre, J., Juraschek, A., & Gehlbach, H. (2018). Teacher-student relationships: The positives and negatives of assessing both perspectives. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 55, 24-38.

- Burke, J., Greenglass, R., & Schwarzer, R. (1996). Predicting teacher burnout over time: Effects of work stress, social support, and selfdoubts on burnout and its consequences. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 9, 261–275.

- Castillo, A., & Montero, C. (2010). La naturaleza del trabajo docente de los profesores de la escuela primaria pública. en. D. Andrade y Feldfeber, M. (Eds.), Nuevas regulaciones educativas en América Latina [New educational regulations in Latin America]: Políticas y procesos del trabajo docente, (pp. 143-163). Lima, Fondo Editorial de la Universidad de Ciencias y Humanidades.

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychologycal Bulletin, 112, 155-159.

- Consejo Nacional de Educación. (2014). Encuesta Nacional a Docentes de Instituciones Educativas Estatales y No Estatales [National Survey of Teachers of State and Non-State Educational Institutions]. http://www.cne.gob.pe/uploads/libro-endo-2014-final.pdf

- Extremera, N., Rey, L., & Pena, M. (2010). La docencia perjudica seriamente la salud: análisis de los síntomas asociados al estrés docente [Teaching seriously harms health: analysis of symptoms associated with teacher stress]. Boletín de Psicología, 100, 43-54.

- Gray, K., & Watson, D. (2007). Assessing positive and negative affect via self-report. En J. A. Coan & J. J. B. Allen (Eds.), Handbook of emotion elicitation and assessment (pp. 171-184), 2007. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gonzáles, R., Gonzáles, M., & San José, C. (2017). Afectividad positiva y negativa en el futuro docente: relaciones con su rendimiento académico, salud mental y satisfacción con la vida [Positive and negative affectivity in the future teacher relationships to your academic performance, mental health, and life satisfaction] Contextos Educativos., 20, 11–26.

- Helsel, D. (2011). Statistics for censorted environmental data using Minitab and R (2th Ed.). Wiley.

- López-Gómez, L., Hervás, G., & Vázquez, C. (2015). Adaptation of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) in a Spanish general sample, 1-23. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289993251_An_adaptation_of_the_Positive_and_Negative_Affect_Schedules_PANAS_in_a_Spanish_general_sample/link/569d2f5a08ae950bd7a669ca/download

- Marenco-Escuderos, A., & Ávila-Toscano, J. (2016). Burnout and mental health issues in teachers: differences related to demographic and social-labor aspects. Psychologia. Avances de la Disciplina, 10(1), 91-100.

- Pithers, T., & Fogarty, J. (1995). Occupational stress among vocational teachers. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 65, 3-14.

- Prieto, M., & Bermejo, L. (2006). Contexto laboral y malestar docente en una muestra de profesores de secundaria [Labor context and teacher discomfort in a sample of secondary school teachers]. British Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 22(1), 45-73.

- Silvero, M. (2007). Estrés y desmotivación docente: el síndrome del “profesor quemado” en educación secundaria [Teaching stress and demotivation: the “burned-out teacher” syndrome in secondary education]. Estudios sobre Educación, 12, 115-138.

- Stanley, K. (2017). Affect and emotion: James, Dewey, Tomkins, Damasio, Massumi, Spinoza. In D. R. Wehrs & T. Blake (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of affect studies and textual criticism (pp. 97-112). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Thompson, R. (2007). Development and validation of an internationally reliable short-form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38, 227-242.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

01 June 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-108-9

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

109

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-149

Subjects

Health, well-being, comprehensive health, psychosocial risks, education, pedagogical processes, social development, human behavior

Cite this article as:

Iraola-Real, I., Bravo-Cunza, J., Blas-Atencia, C., & Nolberto-Quispe, L. (2021). Positive and Negative Affects: The Importance of the Emotions in University Students. In C. Guzmán Torres, & J. V. Barba (Eds.), Psychosocial Risks in Education and Quality Educational Processes, vol 109. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 29-38). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.06.4