Abstract

The article deals with the problem of HIV infection, the causes of its spread, and technologies for working with HIV-infected prisoners. People living with HIV, their relatives and friends have to deal with a complex, fragmented and often unfamiliar system of health, social and psychological services. Statistical data on HIV-infected people in the country and the Chelyabinsk region are also considered. The data of the conducted study of needs concluded with HIV in correctional institutions in December 2019 are presented. The needs of representatives of vulnerable groups, in particular people living with HIV, are determined by the complex nature of medical and social problems, the likelihood of sudden changes in health and emotional mood, leading to the need for frequent adjustments in the process of care. The situation is particularly difficult for people in correctional institutions, places of deprivation of liberty, as well as for their relatives, partners and friends. In this regard, this study aims to demonstrate an objective picture of the needs of people affected by HIV in correctional institutions in the Chelyabinsk region.

Keywords: Availability of services, HIV, people with HIV in correctional institutions

Introduction

AIDS as one of the most important social problems faced humanity at the end of the 20th century. Currently, more than 40 million HIV-infected people are officially registered in the world. In 2017, the number of Russians who were diagnosed with HIV for the first time became a record - 940 thousand people infected with the immunodeficiency virus (Brinkley-Rubinstein, 2018).

HIV infection is a slowly progressive infectious disease caused by the human immunodeficiency virus, characterized by damage to the immune and nervous systems, with the subsequent development against this background of opportunistic (concomitant) infections, neoplasms that lead to death of an HIV-infected person (Bauer, 1990). The immune system becomes susceptible to many diseases caused by other viruses, fungi, parasites, bacteria, especially mycobacterium tuberculosis (Ruzaeva, 2015).

AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) is the terminal stage of HIV infection, characterized by clinical manifestations (a set of certain symptoms and diseases caused by significant disorders of the immune system) (Panchaud & Cattacin, 1997).

It is customary to use the term “People living with HIV” (PLHIV) to refer to a person or group of people who are HIV-positive, as this designation reflects the fact that people can live with HIV for decades by leading an active lifestyle (Kassira et al., 2001).

Problem Statement

Today, on average, HIV-infected people live 15 years. However, early detection of the disease and immediate treatment with modern antiretroviral drugs can significantly lengthen the life of patients. The main role in curbing the developing AIDS is played by the patient's psychological state and his efforts to comply with dispensary observation and the regimen of antiretroviral therapy (Ajong et al., 2018).

In December 2016, about 871 thousand Russians were living with a diagnosis of HIV infection. As of June 30, 2019, the cumulative number of registered cases of HIV infection in the immune blot among citizens of the Russian Federation was 1,376,907 people (according to preliminary data). By the end of the first half of 2019, 1,041,040 Russians living with HIV were living in the country, excluding 335,867 deceased patients. In the first half of 2019, according to preliminary data, 47,971 cases of HIV infection in the immune block were reported in the Russian Federation, excluding those identified anonymously and foreign citizens, which is 7.3% less than in the same period in 2018. (51,744 cases) (Solodovnikova & Suleymanova, 2019). The incidence rate of HIV infection in the first half of 2019 was 32.7 per 100 thousand population in the Russian Federation (Yavon, 2016).

According to Rosstat, in 2010, 57.2 thousand people were diagnosed with HIV, in 2017 - 88.6 thousand new infected. Based on the statistics, the incidence of human immunodeficiency virus has increased 1.5 times over these several years (+ 54.9%) (Hongfei et al., 2017).

People living with HIV, their families and friends have to deal with a complex, fragmented and often unfamiliar system of health, social and psychological services (Romodina, 2018a).

The needs of representatives of vulnerable groups, in particular people living with HIV, are determined by the complex nature of medical and social problems, the likelihood of sudden changes in health status and emotional mood, leading to the need for frequent adjustments in the care process (Smetanina & Kuzminykh, 2018). The situation is especially complicated for persons in correctional institutions, places of deprivation are free, as well as for their relatives, partners and friends (Thapa, Hannes, Buve et al., 2018).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the Joint United Nations Program on HIV / AIDS (UNAIDS) and other international structures, in all countries of the world, the number of HIV-infected among prisoners and convicts in the penitentiary system is 5-10 times higher than among the general population.

Social support, as an important element of support for people living with HIV, aims to meet needs and help overcome difficulties in accessing necessary services. The social support system should be adapted depending on the specific medical and social needs of people with different upbringing and backgrounds and experiencing various problems, in particular, caused not only by the presence of HIV infection, but by the conditions of detention in places of detention (Romodina, 2018b).

Currently, HIV-positive prisoners released from prisons have a low level of adherence to dispensary observation for their illness and to receiving antiretroviral therapy. This fact indicates the need for comprehensive work within the framework of interdepartmental interaction between the penal system, the health care system and socially oriented non-profit organizations (Thapa, Hannes, Cargo et al., 2018). A systematic impact on prisoners with a positive HIV status is required in order to form adherence to dispensary observation and reduce risk behavior in terms of the spread of HIV infection (Fadeeva, 2020).

In this regard, this study is intended to demonstrate an objective picture of the needs of people affected by HIV who are in correctional institutions in the Chelyabinsk region.

Research Questions

The study is devoted to the study of the needs for medical and social services of people infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) who are in the penitentiary system in the Chelyabinsk region, as well as the analysis of their adherence to antiretroviral drugs, dispensary observation and further socialization in society. This study was carried out in December 2019 jointly by the educational and scientific laboratory of socio-economic research of Educational Institution of Higher Education “The South Ural University of Technology” and the Charitable Foundation "Source of Hope" in Chelyabinsk.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study is to assess the need for medical and social services for people with a positive HIV status in penitentiary institutions in the Chelyabinsk region.

Research Methods

The methodological basis of the study is modern approaches in the field of organizing sociological research, supported by analytical methods and advanced developments in this area.

The information-empirical base of the study, which ensured the representativeness of the initial data, was formed on the basis of processing the results of a survey of the target group, as well as an analysis of legislative and by-laws of the Russian Federation. According to the developed questionnaire, in the period from September to November 2019, 402 people infected with HIV were interviewed in correctional institutions in the Chelyabinsk region.

Research objectives:

- Determining the needs of prisoners with a positive HIV status in penitentiary institutions on the territory of the Chelyabinsk region for medical and social support services;

- analysis of the awareness of HIV-positive prisoners in correctional institutions in the Chelyabinsk region about their disease and its treatment;

- Development of recommendations to improve the quality of care for people living with HIV in prisons in the Chelyabinsk region.

The object of the research is HIV-infected citizens who are in correctional institutions in the Chelyabinsk region.

The subject of the research is the needs of prisoners with a positive HIV status in correctional facilities in the Chelyabinsk region for medical and social support services.

Findings

The sample consisted of HIV-positive prisoners who were in custody at the time of the survey. Sample type - multistage, serial (year of HIV disease, health status, professional affiliation).

The representativeness of the sample (n = 402) allows considering the opinion of the respondents as the opinion of all prisoners in the Chelyabinsk region with a statistical error of up to 9.5%. The overwhelming majority, namely 63% of HIV-positive prisoners, are people of average working age, from 30 to 49 years old, a quarter of the respondents - 28% - are fairly young people from 18 to 29 years old (see table 1).

Most of the respondents (36%) have secondary or specialized secondary education, about 15% of the respondents received incomplete secondary education, the option “I have a higher education or incomplete higher education” was indicated by only 8.5%.

Accordingly, most of the prisoners had permanent or temporary work at large, namely 34% worked in blue-collar specialties, 6.5% were managers or chief specialists, and only 10% were unemployed.

The respondents were asked in what year they learned about their diagnosis.

According to the research, it can be said that the bulk of the prisoners learned about their diagnosis in 2010 and 2014 (20 people, respectively), in 2015 there were 26 such people, and since 2016 there has been an increase in the number of prisoners with HIV infection (see table 2).

At the same time, only 260 respondents named the year of infection, which means that 142 (35.3%) of the respondents missed this question on purpose, either they do not remember or do not know the exact time, or have recently become infected and do not accept their disease.

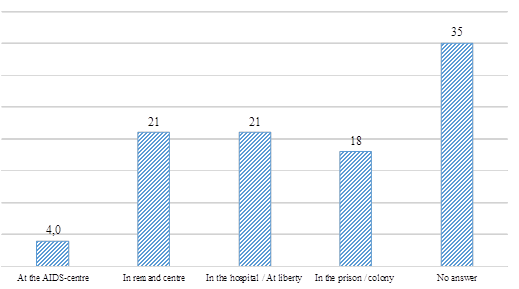

Many respondents named among the places where they learned about their diagnosis "SIZO"- remand centre - and "hospital, polyclinic" by 21%, respectively.

Only 4% applied to the AIDS Center. This fact suggests that one quarter of the respondents, before being taken into custody, practically do not apply to medical institutions for preventive examinations. This means that they continue to lead their usual way of life and infect loved ones. We are talking about the able-bodied young generation. Another quarter finds out their diagnosis in medical institutions, and 18% of respondents - in a colony (see figure 1).

In prisons, there is a risk of transmission of HIV and other infectious diseases. This is because colonies are often overcrowded and violent and fearful.

In the colonies, sexual relations take place, the facts of drug trafficking are noted, the practice of tattooing is widespread. Most often, aggressive prisoners assert themselves in this way.

Protections are often unavailable. Unavailable injecting syringes can be used by more than one inmate, with an increased risk of contracting various infections.

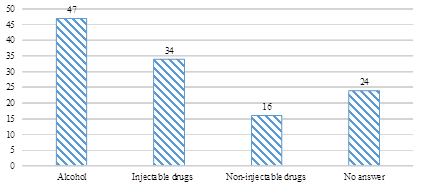

Almost half of our respondents, 47% had problems with alcoholic products, 34% used injecting drugs, 16% suffered from non-injecting drug addiction. Accordingly, the use of psychoactive substances and the practice of risky behavior in relation to the transmission of HIV infection significantly increases the risk of morbidity (see figure 2).

The presence of hepatitis B and C was noted by about 28% of the surveyed young people aged 30 to 49 years, while 10% of them are men, slightly less than half - 17% each, respectively, were observed before incarceration in the penitentiary system by an infectious disease doctor, and 17% - no.

This also suggests that people are afraid to go to register or do not understand the seriousness of the disease, and also do not know where they can apply for free help (see table 3).

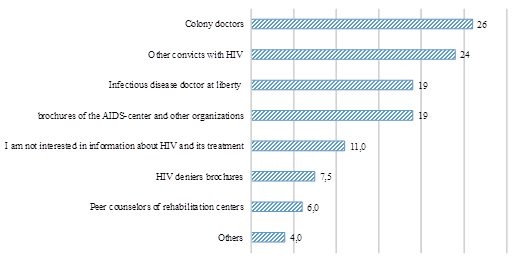

Among the sources of information about HIV infection and its treatment, 26% of prisoners name the colony doctors, 24% receive information from other prisoners with HIV, 19% of the study participants learned about the disease through brochures from the AIDS Center and public organizations (which describe how to live with HIV and take therapy) and from an infectious disease doctor when they were free.

Since most of the respondents receive information through medical personnel, the role of doctors in the colony as the main source of accessible and understandable information about their condition is increasing. It is very important that prisoners understand what kind of life they need to lead in order to improve their quality of life and preserve the function of their internal organs as much as possible (see figure 3).

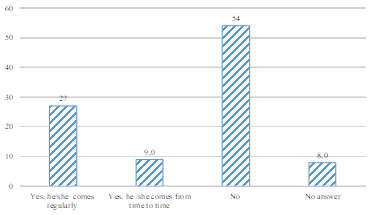

The survey participants answered that only 27% are regularly visited by close relatives (husband, wife), 9% of respondents are visited by relatives from time to time, and more than half of the prisoners (54%) said that no one comes to them (see figure 4).

If a person is imprisoned, he especially desperately needs the support of relatives from the outside. Once in a colony, a person needs to adapt to new conditions; moreover, he also has to stay there for a long time in a confined space with the same people. In correctional institutions, prisoners can be subjected to very severe psychological pressure, both from the staff of the colony and inmates, they can be placed in an isolation ward, punished, etc. All this aggravates the situation of sick people.

Of those who regularly visit for dates, only 9% of spouses are aware of their HIV status and only 5% use barrier contraception constantly during sexual intercourse, and 3% of them sometimes, while 18% of respondents do not use them at all (see table 4).

For those prisoners who answered that their spouses did not come to them, the level of awareness of the diagnosis of a spouse (sexual partner) was higher - 9.5% versus 3% of those who visit regularly or from time to time.

You can also highlight that the questions presented in table. 5 were uncomfortable for the respondents. They either did not want to answer and then skipped these questions, or tried to get away from a direct answer, answering selectively to each of the 3 questions. Which led to the existing picture of the options "no" and "no answer".

This can be explained by the fact that when a young man of working age finds himself in a colony and finds out that he has been diagnosed with HIV infection, he experiences significant stress, one might say “the world begins to collapse overnight.” He has a lot of questions: "what to do?", "How to live further?", And, the most terrible question, "how to tell loved ones, especially a husband or wife?" Many hide their diagnosis from loved ones, because they are afraid to be left completely alone, without the slightest hope that someone will be waiting for them at large, someone will come to them while they are in prison, someone will bring them warm clothes or food ... It is difficult for them to find words, it is difficult to muster courage. The fear of being rejected and unnecessary pushes HIV-infected people to hide their diagnosis and, thus, the risk of infection of partners / spouses increases. It is impossible not to mention also the influence of public opinion, the Internet, as well as the activities of the so-called groups of HIV dissidents who deny the presence of HIV infection and AIDS, that is, they propagate the assertion that these diseases do not exist.

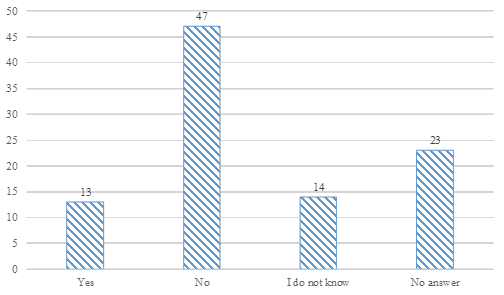

Most of the study participants (47%) indicated that their spouses (sexual partners) do not have a positive HIV status, and this again emphasizes the influence of the fear of loneliness (see figure 5).

At the same time, the overwhelming majority of prisoners (47%) refused to take antiretroviral therapy because they felt good, 17% could not themselves understand the need for therapy. Among the arguments, those who agreed to accept therapy named “believed the doctors” - 30%, “I know a lot about HIV infection and therapy myself” - 28%, and 25% of respondents indicated poor health (see table 5).

Among the participants in the study were those who started taking therapy, but then quit for the following reasons: it seemed that the pills were constantly different - 44%; side effects appeared and did not pass - 39%; decided that HIV does not exist - 8.7%.

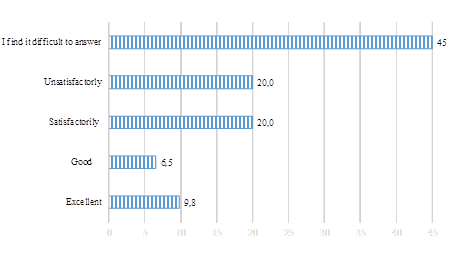

Prisoners with a positive HIV status should receive appropriate medical and social services in places of deprivation of liberty (PDL) and further follow-up after release to maintain adherence to dispensary observation and treatment. 9.8% of the prisoners who answered this question gave an excellent assessment of the medical and social services in the PDL, good - only 6.5%, satisfactory and unsatisfactory marks for 20% of the respondents. Almost half of the respondents (45%) found it difficult to answer, that is, they could not say anything at all (see fig. 6).

It can be concluded that the system of medical and social services in the PDL does not work very effectively. That is, prisoners with HIV status do not receive sufficient assistance.

Today it is necessary to conduct well-coordinated complex work with the joining of efforts of several services and organizations.

Prolonged stay in places of detention leads to social isolation and alienation from the outside world, and people who find it difficult to adapt to new conditions leave the correctional institution. It is especially difficult for those who do not know where to go for help, how to get a job, where to live, and the closest relatives do not intend to help at all.

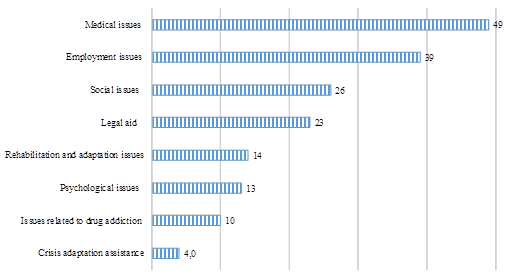

It is practically impossible for HIV-infected people to solve emerging problems without outside help and support. Leaving places of detention, they can start using drugs again, while practicing unprotected sexual relations, becoming a dangerous source of HIV infection (see figure 7).

Initially, we wanted to find out if our respondents know the institutions and organizations to which they can turn for help after release, for medical and social services. It is very difficult for the majority to name at least some institutions. Among the options were: “AIDS Center”, “social protection”,“employment center”, “psychologist”, “narcologist”. It is much easier for them to mark issues of concern to them that they would like to solve after release (see figure 8).

Conclusion

Based on the results of a survey of prisoners with HIV status in correctional institutions in the Chelyabinsk Region in September-November 2019, it can be concluded that the low level of awareness of prisoners about their disease and its treatment, about which institutions they can seek help, lack of support from loved ones are quite acute problems.

There is a low awareness of HIV-infected about their status before entering the pre-trial detention center. Many respondents named among the places where they learned about their diagnosis "SIZO" - remand centre- and "hospital, polyclinic" by 21%, respectively. Only 4% applied to the AIDS Center. This fact suggests that almost a quarter of the respondents, before being taken into custody, do not apply to medical institutions for preventive examinations, which means that they continue to lead their usual way of life and infect loved ones.

Almost half of our respondents, 47% had problems with alcoholic products, 34% used injecting drugs, 16% suffered from non-injecting drug addiction.

HIV-infected people in correctional institutions do not have full and comprehensive access to social, medical and psychological services, including those related to HIV infection, which they need for health reasons.

At the same time, the overwhelming majority of prisoners (47%) refused ARVT because they felt good, 17% needed an explanation of the need to take ARVT. Among the arguments, those who agreed to accept therapy called “believed the doctors” - 30%, “I know a lot about HIV infection and therapy myself” - 28%, and 25% of respondents indicated poor health.

Since most of the respondents receive information through medical personnel, the role of doctors in the colony as the main source of accessible and understandable information about their condition is increasing. It is very important that prisoners understand what kind of life they need to lead in order to improve their quality of life and to preserve the functions of internal organs as much as possible.

Also, prisoners have a high need for consultations from psychologists, narcologists, general practitioners, infectious disease doctors, social work specialists, specialists from employment centers.

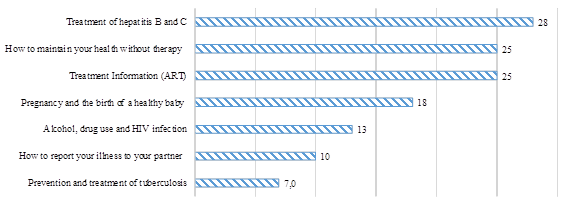

The respondents need informational lectures, brochures, or booklets on such topics as: "Treatment of hepatitis B and C", "How to maintain your health without therapy", "Information about ART", "Pregnancy and the birth of a healthy child".

Based on the survey results, recommendations were developed:

1. To carry out active preventive work among HIV-infected persons under investigation and prisoners in order to ensure timely diagnosis of HIV infection and hepatitis B and C and the initiation of treatment.

2. To create a medical and social bureau, which would unite the efforts of various specialists for effective work on the rehabilitation and socialization of HIV-infected, including HIV-infected, who are in prison. Since the modern penitentiary system is not able to provide medical and social support for people with HIV, and then after release they do not go anywhere, because they do not know, are afraid, ashamed, quit taking therapy, fall under the influence of sects, which ultimately leads to the further spread of HIV infection.

3. Ensure adequate funding for the medical service in the ILC in order to ensure universal access for inmates to the diagnosis and treatment of HIV, hepatitis C and drug addiction in correctional institutions.

4. Optimize the procedure for prescribing antiretroviral therapy to patients in accordance with accepted clinical guidelines in order to remove barriers to treatment.

Acknowledgments

The reported study was funded by South Ural University of Technology, project number 05/19.

References

Ajong, A. B., Njotang, P. N., Nghoniji, N. E., Essi, M. J., Yakum, M. N., Agbor, V. N., & Kenfack, B. (2018). Quantification and factors associated with HIV-related stigma among persons living with HIV/AIDS on antiretroviral therapy at the HIV-day care unit of the Bamenda Regional Hospital, North West Region of Cameroon. Globalization and health, 14, 56.

Bauer, R. (1990). Zwischen Skylla und Charybdis: das intermediäre Hilfe- und Dienstleistungssystem. [Between Skylla and Charybdis: the intermediate aid and service system]. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 2, 153-172.

Brinkley-Rubinstein, L. (2018). Jail and Prison Populations, Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS. In T. J. Hope, D. D. Richman, M. Stevenson (Eds.), Encyclopedia of AIDS. Springer.

Fadeeva, E. V. (2020). Dostupnost' besplatnoj medicinskoj pomoshchi v Rossii: sostoyanie i problemy [Availability of free medical care in Russia: status and issues]. Sociological Studies, 4, 94-104. [in Rus.]

Hongfei, D., Chi, P., & Li, X. (2017). High HIV prevalence predicts less HIV stigma: a cross-national investigation. AIDS Care, 30(6), 714-721.

Kassira, E. N., Bauserman, R. L., & Tomoyasu, N. (2001). HIV and AIDS surveillance among inmates in Maryland prisons. J Urban Health, 78, 256-263.

Panchaud, C., & Cattacin, S. (1997). The contribution of non-profit organisations to the management of HIV/AIDS: A comparative study. Voluntas, 8, 213-234.

Romodina, A. M. (2018a). Vich / Spid: Social'nye aspekty problemy [HIV / AIDS: Social aspects of the problem]. Bulletin of the Council of young scientists and specialists of the Chelyabinsk region, 2(21), 67-70. [in Rus.]

Romodina, A. M. (2018b). Sovremennye zavisimosti molodogo pokoleniya [Modern dependencies of the younger generation]. Bulletin of the Council of young scientists and specialists of the Chelyabinsk region, 3(22), 55-61. [in Rus.]

Ruzaeva, E. M. (2015). Dostupnost' besplatnoj medicinskoj pomoshchi v Rossii: sostoyanie i problem [On the issue of medical care for HIV-infected people as one of the types of social security]. Bulletin of the Orenburg state University, 3(178), 130-137. [in Rus.]

Smetanina, O. V., & Kuzminykh, D. A. (2018). Diskriminaciya i stigmatizaciya VICH-inficirovannyh pacientov [Discrimination and stigmatization of HIV-infected patients]. In Pirogov readings. Materials of the XIV scientific conference of students and young researchers. Nizhny Novgorod, Privolzhsky Research Medical University, 240-243. [in Rus.]

Solodovnikova, E. V., & Suleymanova, F. O. (2019). Problema diskriminacii VICH-inficirovannyh grazhdan v sfere trudovyh otnoshenij [The problem of discrimination of HIV-infected citizens in the sphere of labor relations]. Issues of labor law, 3, 26-31. [in Rus.]

Thapa, S., Hannes, K., Buve, A., Bhattarai, S., & Mathei, C. (2018). Theorizing the complexity of HIV disclosure in vulnerable populations: a grounded theory study. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 162-167.

Thapa, S., Hannes, K., Cargo, M., Buve, A., Peters, S., Dauphin, S., & Mathei, C. (2018). Stigma reduction in relation to HIV test uptake in low- and middle-income countries: a realist review. BMC Public Health, 18, 1277.

Yavon, S. V. (2016). VICH-inficirovannye lyudi: diskriminaciya i narushenie prav [HIV-infected people: discrimination and violation of rights]. Sociological Studies, 6, 142-144. [in Rus.]

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 June 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-111-9

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

112

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-436

Subjects

Personality, norm, pathology, behavior, uncertanity, COVID-19

Cite this article as:

Romodina, A., Valko, D., & Tananin, A. (2021). Assessment Of The Needs Of People With Hiv In Correctional Institutions. In M. Ovchinnikov, I. Trushina, E. Zabelina, & S. Kurnosova (Eds.), Personality in Norm and in Pathology, vol 112. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 96-109). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.06.04.12