Abstract

June 22, 1940 France signed a truce with Hitler’s Germany, which created the pro-Nazi Vichy France that used propaganda posters extensively to demonize communists and Jews to earn Frenchmen’s loyalty to the regime. The ideas were nurtured by Institut d'étude des questions juives (Institute for the Study of the Jewish Problem), the body funded by the German Embassy in Paris. Visual antisemitic propaganda centered around the idea that a “Jewish conspiracy” was the root of all trouble in France, and that Jews were also behind the Bolsheviks and de Gaulle. Propaganda also exploited the French dissatisfaction with the falling living standards: inflation, black market, and unemployment, in an attempt to convince people Jews were to blame. Posters centered around stereotypical, repulsive, dehumanized image of Jews—the image of a murderer and an enemy in disguise that was lurking around and trying to undermine France’s prosperity. Visual propaganda materials heavily relied on the personalized enemy image as exemplified by (Jews and France) exhibition that highlighted the dominance of Jews in the country’s legal, economic, and cultural affairs. The exhibition also sought to teach French citizens to recognize Jews by their stereotypical physical traits. These materials were intended to seed intolerance to Jews in the French, make the people loyal to the pro-German regime and its(Final Solution to the Jewish Question). Mémorial de la Shoah (the Shoah Memorial) in Paris conducted a substantial research to preserve, systematize and provide access to these materials.

Keywords: Antisemitism, Vichy France, visual agitation, propaganda, France

Introduction

Visual images as a complement to verbal propaganda were used in France long before its occupation, namely during WW1 and the Popular Front. On the one hand, since the image dominates over the text, people can retrieve and process information on the poster quickly “on the go”.

On the other hand, history has proved propaganda exhibitions to be a popular and effective tool for manipulating the masses by deploying a whole complex of visuals: images, statues, graphs, quotes, figures, all of which are there to instill a specific ideological concept, to justify and legitimize the regime, to dispel doubt and critical thinking, to create an antagonistic image in order to rally the population around its rulers.

(National Revolution), a concept first mentioned on October 8, 1940 as the common denominator that would bring all French people together under the banner of Marshal Pétain, was based on the idea of bringing back the traditional values, (Work, Family, Fatherland), to replace the Republican one:(Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity). Some of the country’s symbols of state were altered as well. Whilst France did not get rid of its blue-red-white tricolor flag and only placed Pétain’s portrait upon it, Marianne lost here revolutionary Phrygian cap and became a simple woman to personalize France. New France’s Gallic spirit found embodiment in the double-edged poleaxe of the Gauls. July 14, the Bastille Day, remained but a nominal holiday, for which reason the well-known large-scale roundup of Jews that had been planned for the night of July 14, 1942 in Paris was postponed to July 16.

Visual propaganda posters teach people “to think appropriately, to speak appropriately, and to act appropriately”. In this case, image functions as an ideological code whereas the text is a short and concise summary of the message or a call to action.

(National Revolution), a concept first mentioned on October 8, 1940 as the common denominator that would bring all French people together under the banner of Marshal Pétain, was based on the idea of bringing back the traditional values, (Work, Family, Fatherland), to replace the Republican one:(Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity). Some of the country’s symbols of state were altered as well. Whilst France did not get rid of its blue-red-white tricolor flag and only placed Pétain’s portrait upon it, Marianne lost here revolutionary Phrygian cap and became a simple woman to personalize France. New France’s Gallic spirit found embodiment in the double-edged poleaxe of the Gauls. July 14, the Bastille Day, remained but a nominal holiday, for which reason the well-known large-scale roundup of Jews that had been planned for the night of July 14, 1942 in Paris was postponed to July 16.

Problem Statement

This paper covers several issues. How did visual propaganda affect the public views in France?

2.1. What perceptive techniques were utilized by the authors of visual propaganda?

2.2. What methods were used to create a negative image of Jews in the French society?

2.3. What perceptive techniques were utilized by the authors of visual propaganda?

2.4. What methods were used to create a negative image of Jews in the French society?

Research Questions

The authors hereof analyze antisemitic propaganda posters found in high-traffic areas in France as well as the materials of the antisemitic exhibition. Visual propaganda posters teach people “to think appropriately, to speak appropriately, and to act appropriately”. In this case, image functions as an ideological code whereas the text is a short and concise addition to it.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose hereof is to investigate the meaningful symbolism of antisemitic propaganda from the standpoint of its effects on the French society, as well as to systematize the core techniques that were used to influence the public opinion.

Research Methods

This section describes the research methods.

5.1. This research is descriptive in its attempt to analyze the unique contents of posters and exhibits.

5.2. It also relies on typology to classify the studied objects by the method they use to convey the ideas behind them.

5.3. Finally, the authors use deduction, or transition from premises to a more general conclusion, to uncover the symbolism behind some of the elements of visual propaganda.

Findings

Collaborationist policies manifested, among other things, in copying the Nazi view and treatment of Jews, Gypsies, and Freemasons (Cherkasov, 2019). Vichy France painted Jews as the ‘source of all trouble’, the so-called “aliens” that also included communists, de Gaulle supporters, Freemasons, etc., which is why Vichy media often referred to Jews as the allies of communists or de Gaulle. France also had antisemitic posters in the languages of the occupied European nations on public display (Beaurepaire, 2016). We feel compelled to agree with Valter (2016) that a political poster must evoke an emotional state that could be referred to as a “feeling of the highest order. It, in fact, is a set of feelings associated with a variety of ideological, social, and political views including patriotism, the view of labor and civic duties, etc. Every person receives input from all the channels they have access to; however, some channels are more important for communication, and visual communication is the most important one.

6.1. Nazi ideas were mainly spread in France by Institut d'étude des questions juives (Institute for the Study of the Jewish Problem), founded in May 1941 for the purposes of “research and education”. The body was financed by the German Embassy’s Information Center and personally by Gestapo’s Theodor Dannecker.

6.2. The Institute’s propaganda campaign produced numerous books on top of (The Yellow Notebook), a periodical; besides, the Institute made multiple posters and organized, an exhibition that was hosted by Palais Berlitz and presented “research” by Georges Montandon, a well-known anthropologist and the author of (How to Recognize a Jew?) In addition to the newest data of the time, the exhibition revolved around thousand-year old accusations of Jews including the myth of ritual killings of non-Jewish children that had caused heinous pogroms in the past (Perrault, 1987).

6.3. Propaganda was in fact a success, as it sparked an ever stronger antisemitic sentiment, especially in the Free Zone, where many Jews had been lucky to find refuge. This success stemmed from the substantial decrease in France living standards, in particular, because of inflation and the emergence of the black market. When social tension builds up, people need a real-world target to let off steam, and that target is often the “enemy”. The image of the “enemy” begins circulating in mass media, literature, and arts, and is easily absorbed by people who are ready to “live in an echo chamber” (Labutina, 2015).

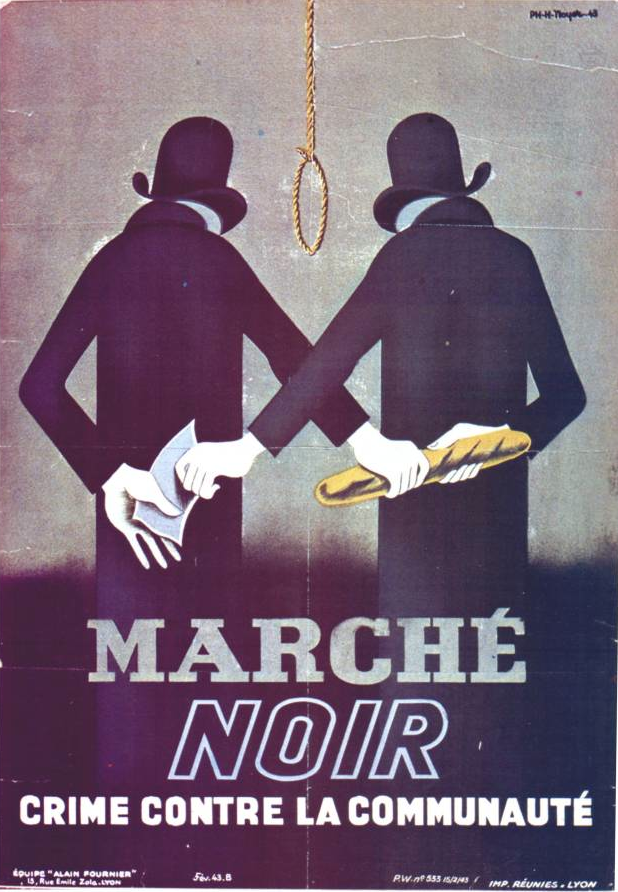

Thus, the poster (Black Market: Crime Against the Community) shows recognizable stereotypical silhouettes of tall men in coats and hats. Accusations of illegal trade, seizure, circumvention of the law, audacious enrichment, non-poverty, elevated welfare, and unburdened life...gave rise again to all the negative stereotypes associated with Jews and filled the police reports (Laborie, 1990).

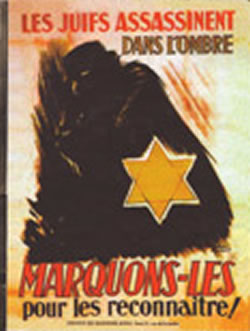

6.4. The image of a Jewish murderer was deemed a good enough excuse to force all Jews to expose themselves by wearing a Jewish chest insignia; this image found a physical manifestation in the poster below: a dark spot that can still be recognized as the silhouette of a knife-armed Jew as betrayed by the bright yellow six-pointed star. The text translates as “Jews kill from the shadows, so let’s mark them for recognition”. Since May 1942, all Jews in France were forced to wear this yellow six-pointed star, and Le Matin, an influential newspaper at the time, wrote of the “surprise” the French were caught by as they learned how many Jews they had at work and in the neighborhood (Ganier, 1975).

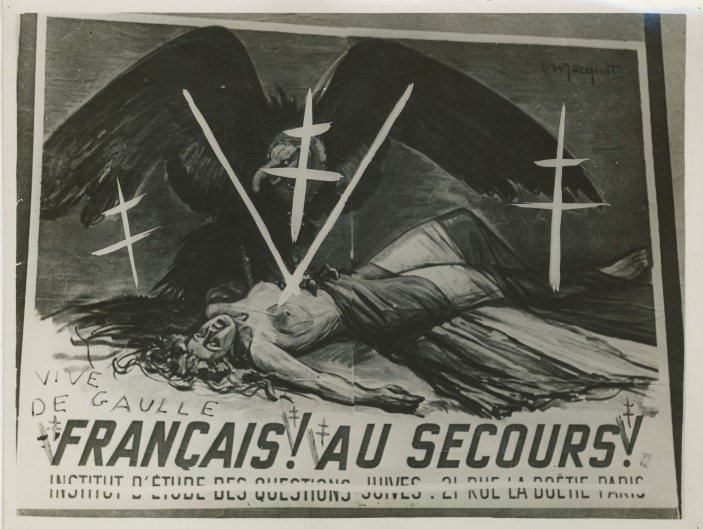

6.5. One poster dehumanizes a Jew by showing him as a vulture, with the long and hooked beak being the stereotypical ethnic feature for recognition. The bird holds captive a woman that it has pinned to the ground; the woman’s screaming, “The French, help me!” However, in this particular poster that is shown hereinunder, unknown Resistance fighters drew three Lorraine crosses on top of the bird and transformed some of the text into Vs for, which is French for victory; they also wrote, “Vive de Gaulle” (Long live de Gaulle).

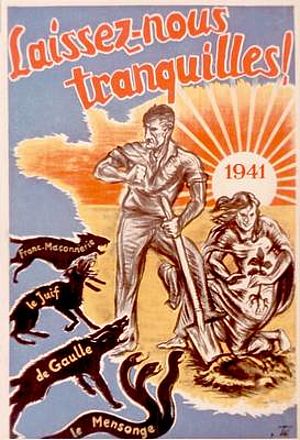

6.6. (Leave us alone!) is another poster that shows a dehumanized Jew as well as a dehumanized de Gaulle; the text is an outcry of farmers that are planting the sprouts of New France in the south of the country whilst being attacked from the west by four predators: lies represented by a hydra, de Gaulle as a hyena, Jews as a jackal, and Freemasons as a wolf.

The farmers, a man and a woman (in fact a typical image in Vichy propaganda) are trying to plant the sprouts of New France using available tools.

6.7 August 4, 1941 General de Gaulle made a statement of the antisemitic Vichy acts, calling them “invalid and ineligible in Free France” (Badinter, 1997).

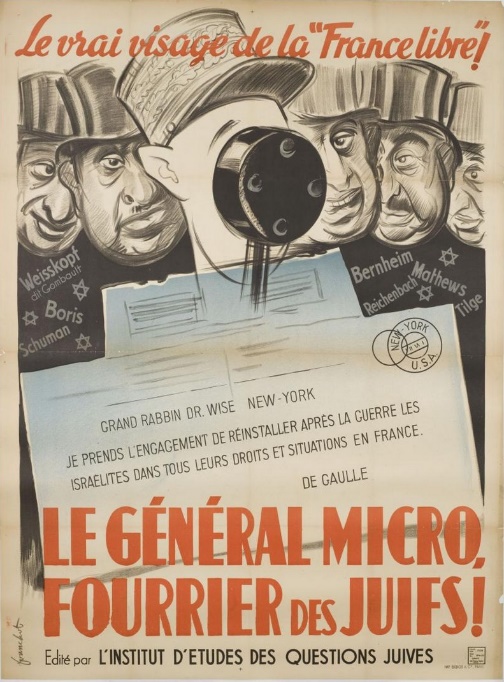

For this reason, de Gaulle was portrayed together with Jews in this poster, (The Real Face of Free France) De Gaulle hides behind the microphone but can still be recognized by his large ears and a képi; however, the stereotypical Jewish faces behind him are hard to miss. The lower text,(General Microphone, the Harbinger of Jews!), apparently refers to the General’s famous speech delivered in a BBC broadcast from London on June 18, 1940, as well as to his further broadcasts. The small text cites de Gaulle’s telegram to the Chief Rabbi of NYC, “I hereby commit to restore the Israelites in all their rights and statuses after the war is over.”

The research of this matter was boosted when French President J. Chirac recognized in 1995 that French be responsible for the persecution of Jews, since the Vichy government was still French (Gugnina, 2017). Later, on July 22, 2012 this statement was reinforced by Francois Hollande on the 70th anniversary of the Vel' d'Hiv' Roundup (Poliakova, 2016).

Conclusion

7.1. The image of Jews in Vichy France was associated with specific symbols (the Jewish star), colors (usually black and yellow), personalization (certain historical figures were portrayed), stereotypes (facial features and clothing with a strong Jewish connection), and dehumanization (showing Jews as animals or birds of prey). Activity-wise, Jews were portrayed as murderers, destroyers, occupiers, molesters, robbers, conspirators, supporters of anti-Hitler movements, and enemy of France.

7.2. General contexts can be summed up as follows: Jews want to prevent France’s revival brought by the National Revolution, seek global hegemony, support de Gaulle and the anti-Hitler coalition; finally, every non-Jew must be able to identify Jews and isolate them in a crowd.

Acknowledgments

The Shoah Memorial is a museum and documentation center and collects and publishes materials on the Holocaust in France. The authors hereof thank the Memorial for their assistance in collecting evidence for this paper.

References

Badinter, R. (1997). Un antisémitisme ordinaire. Vichy et les avocats juifs (1940-1944) [Ordinary antisemitism. Vichy and the Jewish lawyers (1940-1944)]. Fayard. [in French].

Beaurepaire, P.-Y. (2016). Le complot juif contre l’Europe. [The Jewish plot against Europe]. Histoire par l'image. https://histoire-image.org/fr/etudes/complot-juif-contre-europe [in French].

Cherkasov, P. (2019). Marshal Peten [Marshal Petain]. Modern and Contemporary History, 3, 204-218. [in Russ.].

Ganier, R. Ph. (1975). Une certaine France. L’antisémitisme 40-44. [A certain France. Antisemitism 40-44]. Balland. [in French].

Gugnina, O. (2017). Dialog istorikov o Holokoste [Historians’ dialogue on holocaust]. Science and world, 8, 111-112. [in Russ.].

Laborie, P. (1990). L’opinion française sous Vichy. [French opinion when Vichy]. édition du seul. [in French].

Labutina, T. (2015). K voprosu ob etnicheskih stereotipah v istoricheskoj imagologii: Transformaciya obraza «chuzhogo» v obraz «vraga». [To the question of ethnic stereotypes in a historical imagologiya: transformation of an image of "stranger" into image of "enemy"]. The Journal of Education and Science “Istoriya”, 7. https://history.jes.su/s207987840001223-4-1 [in Russ.].

Perrault, G. (1987). Paris sous l’occupation. [Paris under occupation]. Torino: «Belfond» [in French].

Poliakova, N. V. (2016). Politika pamyati v sovrmennoj Francii: meezhdu kollaboracionizmom i soprotivleniem [The politics of memory in modern France: between collaboration and resistance]. Vestnik tomskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta-filosofiya-sotsiologiya-politologiya-Tomsk State university journal of philosophy sociology and political science, 3(35), 192-199. [in Russ.].

Valter, H. (2016). Politicheskij plakat – zerkalo svoego vremeni. [Political poster – the mirror of the time]. Journal of Historical, Philological and Cultural Studies, 3, 143-149. http://apps.webofknowledge.com.ezproxy.usr.shpl.ru/full_record.do?product=UA&search_mode=GeneralSearch&qid=7&SID=F5L1miBiBanD7l1HJEv&page=3&doc=25 [in Russ.].

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

21 June 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-110-2

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

111

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1168

Subjects

Social sciences, education and psychology, technology and education, economics and law, interdisciplinary sciences

Cite this article as:

Evgenievitsh, G. V., Yakovlevitsh, R. G., & Vladimirovitsh, K. S. (2021). Jews Stalking Behind: Anti-Semitism In France’s Propaganda Posters In 1940-1944. In N. G. Bogachenko (Ed.), Amurcon 2020: International Scientific Conference, vol 111. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 372-379). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.06.03.50