Abstract

English has accumulated a large number of bright expressions throughout its history, its phraseology being its treasury. Phraseological units reflect the history and culture of a nation, the mode of life and consciousness. These units represent a significant, widely used layer of vocabulary, among which phraseological units containing animal names are of particular interest. Animals play a crucial role in the advancement of human life: animals have always been omnipresent in people’s lives; there are countless examples of interaction between humans and animals. In some countries, certain animals, such as a cat in Egypt or a cow in India, were of great symbolic importance and had a sacred status. Primitive people used animals in rituals, and, according to some linguists, it is the ritual, that generated the language to exist. Therefore, the significant role of animals is expressed in a language and a culture. The research focuses on determining the role of phraseological units with the zoonym component, their linguistic cultural and stylistic features. The studies of phraseological units can contribute to a higher level of cross-cultural awareness. Phraseological units with the zoonym component are also widely used nowadays and important for effective cross-cultural communication. Modern fiction and songs provide perfect examples of phraseological units under consideration that prove to be of great cultural importance.

Keywords: Phraseological unit, idiom, the zoonym component, linguistic and cultural peculiarities, sources of phraseology

Introduction

Akhmanova (1966) defines the phraseological unit as a phrase in which the semantic solidity (integrity of nomination) dominates over the structural separateness of its constituent elements. As a result, it functions as an equivalent of a separate word in the sentence. According to academician Vinogradov (1977), a phraseological unit is a combination of words which are semantically integral in the sense that the meaning of the whole is not deducible from the meanings of the constituent elements.

Remote ancestors believed in the existence of kinship between men and animals. People chose animals, making them symbols of clans and tribes, i.e. totems. The animal became sacred, and it could not be killed or eaten. Totemism was widespread among all peoples, and its remnants have been preserved in religion (Sakaeva, 2008). It is especially true for domestic animals that helped people in their work and provided food.

Problem Statement

The primary purpose of our paper is the study of English proverbs and sayings with the zoonym component. The following tasks constitute the foundation of our research: 1) to classify English idioms, proverbs and sayings with the zoonym component; 2) to describe their ethnic identity; 3) to study their origin; 4) to analyze their stylistic features.

Research Questions

Research questions focus on determining the role of phraseological units with the zoonym component, their linguistic cultural and stylistic features.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of our research is to give a comprehensive study of English proverbs and sayings with the zoonym component aiming to provide useful information on English phraseology that can appeal to a broad audience interested in this field of linguistics.

Research Methods

The research was based on the following theoretical research methods: synthesis, classification, quantitative analysis and semantic interpretation. The psychological mechanism of these methods allows us to process, verbalize and interpret the meaning, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the analyzed phraseological units.

Findings

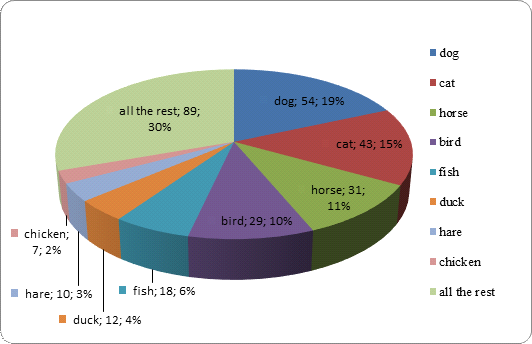

The research revealed 292 phraseological units with the zoonym component (Clarke, 2009; Flavell & Flavell, 1992; Kunin, 1984; Litvinov, 2000) that were classified according to the dominant zoonym component.

A dog has long been considered a person’s friend. However, there are not so many expressions that emphasize the best qualities of a dog. In English, more than 90% of phraseological units with the zoonym component characterize these animals negatively:;;;;. The dog in these expressions is an offended and persecuted creature. It seems greedy and quarrelsome:;.

Like dogs, cats are not carriers of positive qualities: to turn a cat in pan; a fat cat; to move like a scalded cat; a cat in the meal; like a cat on hot bricks; as nervous as a cat; a scaredy-cat; as weak as a cat; a copy-cat; to look like something the cat brought/dragged in; to let the cat out of the bag; to put/set the cat among the pigeons. In Russian phraseology a cat represents a sleazy strange woman: драная кошка (a ragged cat), как угорелая кошка (as a hey-go-mad cat).

Horses played a prominent role in the peasant economy. Their strength and hard work are reflected both in Russian ((as tired as a horse),(to work as a horse)) and English set-expressions;The English language also contains a lot of phraseological units related to hunting and horseracing:;.

Wild animals are less represented in phraseological units than domestic ones. Animal images were formed under the influence of various beliefs. The attitude to the same animal in different countries is not similar (Belyaeva, 2019). However, the wolf is a symbol of cunning, treachery and cruelty for many nations, as seen in the example of English and Russian phraseological units;;(as hungry as a wolf);(a wolf rule/law);(to look as a wolf).

The most widely represented phraseological units are tested to be those with the lexeme– 54 phraseological units, e.g., the tail wagging the dog; not to have a dog’s chance; to teach an old dog new tricks; barking dogs seldom bite; dog eat dog; don't teach a dog to bark; a good dog deserves a good bone; let sleeping dogs lie; to be like a dog with two tails; a living dog is better than a dead lion; dogs bark but the caravan goes on, there's life in the old dog yet, etc.

According to the frequency of use, the second-best component is the lexical unit included in 43 phraseological units, e.g.,;;;;;

Taking the third place, the lexeme is used in 31 phraseological units, among them: to be on one’s high horse; to play horse; a stalking horse; to be on one’s hobby-horse; from the horse’s mouth; to ride two horses at the same time; to flog/to beat a dead horse; hold your horses, etc.

29 phraseological units contain the lexeme: a night bird; A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush; birds of a feather (flock together); a little bird told me; to be a bird-brain; to kill two birds with one stone; the early bird catches the worm; old birds are not caught with chaff. Names of specific birds (not only the word bird) may also occur as components of phraseological units: to be up with the lark; to watch with an eagle eye; parrot-fashion; to be as sick as a parrot.

The frequency of use of lexical units is 18, 12, 10 and 7 times, respectively, e.g.: to feel like a fish out of water; to have other fish to fry; a different kettle of fish; like shooting fish in a barrel; there’s something fishy about this; to cry stinking fish; to swear like a fish-wife; to drink like a fish; chicken feed; to run around like a chicken with its head cut off/like a headless chicken; to be no spring chicken; better an egg today that a hen tomorrow; to take to smth. like a duck to water; a lame duck; to be like a rabbit caught in the headlights; to run with the hare and hunt with the hounds.

There are also names of other domestic and wild animals and birds used in the phraseological units ‒ wolf, monkey, pig, bee, fly, bull, lamb, mouse/rat, goat, sheep, goose, bug, owl, butterfly, worm, snake, lion, donkey, insects, and others: a lone wolf; to be as funny as a barrel of monkeys; to squeal like a stuck pig; sweat like a pig; to happen when pigs fly; as busy as a bee; to have a bee in one’s bonnet; to follow a bee-line; to take the bull by the horns; in two shakes of a lamb tail; to be poor as a church mouse; to smell the rat; to separate the sheep from the goat; to kill the goose that lays the golden eggs; smb’s goose is cooked; everything is lovely and the goose hangs high; to be beaten by the bug; to be as crazy as a bedbug; to be drunk as an owl; to have butterflies in one’s stomach; a social butterfly; a worm's eye view; a can of worms; a snake in the grass; as brave as a lion; the lion's share; feed smb. to the lions; Hares may pull dead lions by the beard; to do the donkey work; to have ants in your pants, etc.

The results of this study can be presented in Figure 1.

According to Telia (1966), the phraseological composition of the language is a mirror, in which the linguistic and cultural community recognizes its national identity, i.e. customs and traditions, historical events, personalities. Phraseology, as part of the language, has a direct relation to the culture and history of the people (Shirokova, 2019) reflecting its most significant stages as sources of phraseological units. The largest sources include borrowings from the Bible, English literary works, borrowings from other languages and English realities.

The enormous influence of the Bible on English is evident from the following phraseological units: to worship the golden calf, a fly in the ointment, a lost sheep, to cast pearls before swine, a wolf in sheep's clothing, the fatted calf, Can the leopard change his spots? Most of them were assimilated so firmly into the language that they ceased to be associated with the Bible.

The most valuable source of phraseological units are works of literature, directly reflecting a particular period of language history. According to Kunin (1996), works by W. Shakespeare are second-best after the Bible in the number of phraseological units to enrich the English language. The following units go back to Shakespeare's works:

W. Scott introduced, J. Swift is responsible for. L. Carroll in his series created very unusual characters by giving them certain distinctive features that led to the evolvement of the idioms and.

The third source of origin of phraseological units with the zoonym component are adoptions from different languages (Amosova, 1989; Arnold, 2002). Mostly they are phraseological units of Romanic origin (Latin, Italian, French, Spanish). A large number of English idioms originate from Ancient Rome as well as from antique mythology, history, culture, and literature. The Roman invasion, the adoption of Christianity, the development of British colonialism, trade and cultural relations with different countries enriched the English vocabulary substantially. So, the following phraseological units can be attributed to the Latin language:;;;;Some phraseological units like;;;; were adopted from the French language.

A small number of phraseological units are adoptions from other languages: to go to the dogs (German); to let the cat out of the bag (German); every dog is a lion at home (Italian); a wolf in sheep's clothing (Greek); to rise like a phoenix from its ashes (Greek); to kill the goose that lays the golden eggs (Greek); the lion’s share (Greek); to cherish a viper in one’s bosom (Greek); an ugly duckling (Danish).

A lot of phraseological units came to England from the American English (Zubayraeva, 2020) and the Australian English, they belong to intralingual adoptions:;;;(AmE); (AuE).

A lot of phraseological units of the English language are primordial English phrases connected with historical facts as well as with beliefs, customs and traditions of English people that can be illustrated with the following idioms:

- “To fight like Kilkenny cats” means to engage in a mutually destructive struggle; to fight almost to death. Kilkenny cats denote two cats fabled to have fought until only their tails remained, hence combatants fight until they annihilate each other. The phrase alludes to an Irish fable in which two cats fought and nearly killed each other.

- “I might as well be hung for a sheep as a lamb” is said to mean that because the punishment for a bad action and an even worse one will be the same, you have no reason not to do the worse one. In the past people who stole lambs were killed, so it was worth stealing something more because there was no worse punishment.

- “To call off one’s dogs” means to stop attacking or criticizing someone. This idiom is related to the English tradition of hunting.

- “To have a bee in one's bonnet” means to keep talking continuously about what other people do not find equally important. This phrase is an alliterative and metonymic transformation of the earlier one’s head full of bees. This term was first found in a translation of Virgil’s “Aeneid”.

- “A black sheep” means a person who has done something bad that brings embarrassment or shame to his or her family. In the 18th- and 19th-century England, according to an old popular belief, the sheep with black wool was seen as carrying the mark of the devil.

As the research has shown, despite most phraseological units with the zoonym component express the spirit and identity of the nation, their etymology may fail to be traced.

Conclusion

In our research we selected and studied about 300 phraseological units with the zoonym component. Found in fiction, press, and lyrics, phraseological units were classified according to the dominant lexical units and source of origin.

The correct interpretation of phraseological units is vital to understand cultural, historical, social and linguistic specificity of a foreign language (Sulima, 2019; Tsvetkova & Mineeva, 2019). We can state that the study of phraseological units can contribute to a higher level of cross-cultural awareness (Sokolova & Plisov, 2019); without them effective communication (Kirillova et al., 2019) between people of different communities and cultures is impossible (Dzyuba et al, 2020).

In their semantics phraseological units reflect a long process of development of the people’s culture, record and transmit cultural attitudes from one generation to another. The metaphorical meaning of phraseological units with the zoonym component reflects cultural specificities. The idioms can be more or less unknown to native speakers of other languages because of the relationship between the language and the culture. Therefore, phraseological units can cause problems when a non-native speaker tries to decode or translate them. Thus, methods of translation of phraseological units with the zoonym component are of great interest to our further research.

References

Akhmanova, O. S. (1966). Dictionary of linguistic terms. Book house “Lybrocom”.

Amosova, N. N. (1989). Basics of English phraseology. Prosveschenie.

Arnold, I. V. (2002). Stylistics. Modern English (4th ed.). Flinta, Nauka.

Belyaeva, I. V. (2019). The Interpreting Nature of Phraseological units with zoonym component. Issues of Cognit. Linguist., 3, 103–109.

Clarke, Y. (2009). How Idioms Work: Resource Book. Garnet Publ. Ltd.

Dzyuba, E. M., Zakharova, V. T., Ilchenko, N. M., Latuhina, A. L., & Sheveleva, T. N. (2019). Intellectual Resource as a Factor of Ensuring National and Cultural Security in the Conditions of the Training Course “Teacher of Russian as a Foreign Language”. In Institute of Scientific Communications Conference (pp. 477-483). Springer.

Flavell, R., & Flavell, L. (1992). Dictionary of Idioms and their Origins. Kyle Cathie Ltd.

Kirillova, N., Savenkova, E., Lazarevich, S., Khaibulina, D., & Diudiakova, S. (2019). Public Speaking Skills In Educational Space: Russian Traditions And Americanized Approach. Amazonia Investiga, 8(21), 617-632.

Kunin, A. V. (1984). English-Russian Phraseological Dictionary (4th ed.). Russ. lang.

Kunin, A. V. (1996). Phraseology of modern English. Int. Relations.

Litvinov, P. P. (2000). English-Russian Phraseological Dictionary with Thematic Classification. Yakhont.

Sakaeva, L. R. (2008). Phraseological Units with the zoonym components, describing a person as an object of comparative analysis of the Russian and English languages. Izv. Herzen univer. J. of human. & sci., 62, 43–47.

Shirokova, E. N. (2019). Methods of text analysis as university subject: cognitive and discursive aspect. Philolog. Class, 57(3), 13–18.

Sokolova, M., & Plisov, E. (2019). Cross-linguistic transfer classroom L3 acquisition in university setting. Vest. of Minin Univer., 7(1(26)). https://vestnik.mininuniver.ru/jour/article/viewFile/927/710.pdf

Sulima, I. I. (2019). The ontological status of language in education. Vest. of Minin Univer., 7(4). https://vestnik.mininuniver.ru/jour/article/view/1047/762

Telia, V. N. (1966). What is phraseology? Nauka.

Tsvetkova, S. Y., & Mineeva, O. A. (2019). Concept of intercultural communicative competence forming in the sphere of business foreign language communication of master degree students. The Tidings of the Baltic State Fishing Fleet Academy: Psychol. and pedag. Sci., 2(48), 192–201.

Vinogradov, V. V. (1977). Selected Works. Lexicology and lexicography. Nauka.

Zubayraeva, M. U. (2020). Figurative phraseological units in the novels of English and American writers. Baltic Human. J., 9(1(30)), 236–238.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

17 May 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-106-5

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

107

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2896

Subjects

Science, philosophy, academic community, scientific progress, education, methodology of science, academic communication

Cite this article as:

Belova, E. E., Arkhipova, M. V., Gavrikova, Y. A., Mineeva, O. A., Nikolskaya, T. E., & Zhernovaya, O. R. (2021). The Linguistic Cultural Analysis Of Phraseological Units With The Zoonym Component. In D. K. Bataev, S. A. Gapurov, A. D. Osmaev, V. K. Akaev, L. M. Idigova, M. R. Ovhadov, A. R. Salgiriev, & M. M. Betilmerzaeva (Eds.), Knowledge, Man and Civilization - ISCKMC 2020, vol 107. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 158-164). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.05.21