Abstract

This paper describes the evolution of Israeli high-school students' choice of the options: "Other solutions" or “I have no opinion” in response to moral dilemmas presented to them in the Moral Attitude Questionnaire. The questionnaire contained different statements describing seven Holocaust moral dilemmas and seven post-Holocaust moral dilemmas. The study aimed to test whether the Holocaust Learning Program generated changes in the evolution of the choice of Other solutions" and “I have no opinion” responses by the participants when asked to respond to the seven Holocaust moral dilemmas and the seven Post-Holocaust era moral dilemmas. 102 male and female students in three Israeli high-schools, responded to the Moral Attitudes Questionnaire at three time points (T1-T3) during their studies in the Holocaust Learning Program at their school. The results indicated that as the research progressed through three different stages, there was a clear decrease both in the number of "Other solutions" and “I have no opinion” options. The main conclusion is that the learning process, which provided more knowledge and clarified the issue of Holocaust moral dilemmas, along with maturation processes over time and participants’ increased motivation reduced the use of both "I have no opinion" responses and the writing of "Other solutions".

Keywords: Moral dilemmasopinionsmoral solutions

Introduction

The Jewish Holocaust involved the systematic murder of more than six million Jews by the Nazis during World War II (1939-1945). It has been discussed, investigated, taught and learned from many perspectives and viewpoints over many years. Nevertheless, the moral perspective is one of the most interesting but less investigated aspects of the Holocaust (Browning, 2004; Farabstein, 2002; Goldhagen, 1998; Zimerman, 2013). From the Jewish viewpoint, morality is considered in relation to four main dimensions: the Nazis who exterminated the Jews, the governments and individuals who assisted the Nazis, the free world and especially the countries who fought against Nazi Germany, who undertook or did not undertake actions to save the Jews and finally the Jews’ own actions in order to cope with the Holocaust. For Israeli youth who study the subject of Holocaust at high-school in Grades 11 and 12 the issue of morality is a very sensitive-emotive topic.

The connection between emotions and other aspects of moral thinking and moral decision-making has been increasingly studied in cognitive psychology and neuroscience in the time that has passed since the early work of Kohlberg (1973) and especially over the last decade (Cushman & Greene, 2012). Contemporary approaches have begun to appreciate and to study the complex interplay and connections between affective reactions and cognitive reasoning in moral decision-making (Greene, 2011). Research has revealed that emotions are involved in socio-moral concerns and dilemmas that involve conflict between socio-moral norms. The study of such dilemmas has provided researchers with an excellent testing ground for the role of emotions in moral decision-making (Cushman & Greene, 2012). Contemporary research also indicates that social norms usually oppose harmful actions against other people, and it has been suggested that an emotional aversion to harming others may have evolved as part of humans’ decision-making (Haidt, 2007). Recent studies support the natural assumption that when the individual is exposed to the experience of harming other people, it triggers strong emotional reactions that are also expressed in cognitive and physiological dimensions especially if the harmful action involves physical force like intentional killing (Cushman et al., 2006; Greene et al., 2004).

Greene et al. (2001) and Greene et al. (2004) indicated that situations in which harming another person is justified are usually and normally accepted for the purpose of social welfare, mainly in extreme conditions. Several lines of evidence indicate that emotions play a significant role in moral decision making. Early functional neuroimaging studies showed that responding to H2S (the utilitarian “harm to save") moral dilemmas (where one must decide whether to kill another person in order to save more lives) involves activity in brain areas associated with emotional reactivity, emotion regulation and social cognition. There are two possible courses of action in these dilemmas: refusing to harm another person, despite all possible consequences or saving as many people as possible even at the cost of harming one person: the H2S decision (Koenigs et al., 2007).

Experimental stress conditions induced in healthy volunteers reduce the proportion of utilitarian choices in moral dilemmas (Starcke et al., 2012; Youssef et al., 2012). These landmark results suggest that emotional experience might promote the choice of deontological decisions in moral dilemmas, and overcoming this bias would involve emotion regulation.

It has recently become clear that abstract judgment and personal choice of action in moral dilemmas rely on distinct psychological and neural processes. When participants have to judge the moral acceptability of a utilitarian course of action in a moral dilemma and then report their own choice of action, they make more deontological judgments, but also more utilitarian choices (Tassy et al., 2013).

In addition, variations of the affective proximity between participants and the potential victim, for example a family relative, have been described as influencing moral choice, but not moral judgment (Tassy et al., 2013). It was also suggested in recent studies that in addition to prospective thinking and social emotions, which probably contribute to moral decision–making in general, moral choice may also involve increased self-focused emotions relating to moral judgment (Tassy et al., 2012). These findings raise the question of whether emotion regulation influences moral choice.

Christensen et al (2014) tried to look for variables known to influence moral judgment, in order to find out which of them matters most, and how they interact. One main result of their work is that, when dilemmas are validated, a more complex pattern appears and it is revealed that moral judgments are reached by a combination of deliberation, deontological thinking and arousal of emotions.

This paper discusses whether the Holocaust Learning Program generates changes in the evolution of “No opinion” and "Other solutions" responses expressed by the participants with regard to Holocaust and Post-Holocaust moral dilemmas.

Problem Statement

Previous research on moral dilemmas has not tested the evolution of “No opinion” and "Other solutions" responses given to moral dilemmas faced by Jews during and after the Jewish Holocaust.

Research Questions

The research question: Did the Holocaust Learning Program generate changes in the evolution of “I have no opinion” and "Other solutions" chosen by the participants to respond to Holocaust and Post-Holocaust era moral dilemmas.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to test whether the Holocaust Learning Program generates changes in the evolution of “I have no opinion” and "Other solutions" responses chosen by the participants in response to Holocaust and Post-Holocaust era moral dilemmas.

Research Methods

-

Participants. 102 Israeli high school students, male and female participated in the study. They were studying in three different high schools in Israel and their ages ranged from 17-18. They all took part in the study voluntarily. All of them belong to the third and fourth generation after the Jewish Holocaust, and some of them had relatives who were Holocaust victims or survivors.

-

Procedure. The research was conducted over two academic years from January 2015, when the students were in the middle of Grade 11 and until January 2016, when they were in the middle of Grade 12. The research instrument was a Moral Attitudes Questionnaire which contained statements describing seven Holocaust era moral dilemmas and another seven post-Holocaust era moral dilemmas. The questionnaire was administered at three timepoints during the research period: Measurement 1 took place when the students were in the middle of Grade 11 in January 2015, at the beginning of the formal learning process for matriculation exams in Jewish Holocaust history and when they were preparing for a journey to visit Holocaust memorial sites in Poland. Measurement 2 took place after the students returned from the journey to Poland in September 2015, at the beginning of Grade 12. Measurement 3 took place in January 2016 in the middle of Grade 12, when the students completed their matriculation exams in Holocaust studies.

-

The research tool used in this study was a specially developed closed-ended questionnaire investigating the participant's moral attitudes towards Holocaust and post-Holocaust era moral dilemmas. The questionnaire was developed on the basis of pioneering work by Kohlberg (1973) and his followers including the work of Foot (1967) and Graham et al. (2011). The dilemmas were chosen because they stand out after comprehensive review of the relevant literature regarding the Holocaust and post-Holocaust eras. Two contradicting alternative solutions were given for each dilemma. All the dilemmas and solutions were historically authentic. Participants were requested to indicate their personal attitude concerning the two different suggested solutions, A or B, for each dilemma on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 = strongly disagree, and 5= strongly agree. They could choose to relate to one solution (A or B), or to both solutions, A+B. Alternatively, they could mark the response “I have no opinion” or write another solution of their own.

-

Data analysis including descriptive statistics analysis was used to present the evolution of the participant's choices for "Other solutions" and “No opinion” along the different measurement times (T1-T3).

This paper presents only the results regarding the evolution of the participants’ choice of the options: "Other solutions" and “No opinion” for moral dilemmas as they were used by the participants to respond to the Moral Attitude Questionnaires at three timepoints (T1-T3) in parallel to the Holocaust Learning Program at school;

Findings

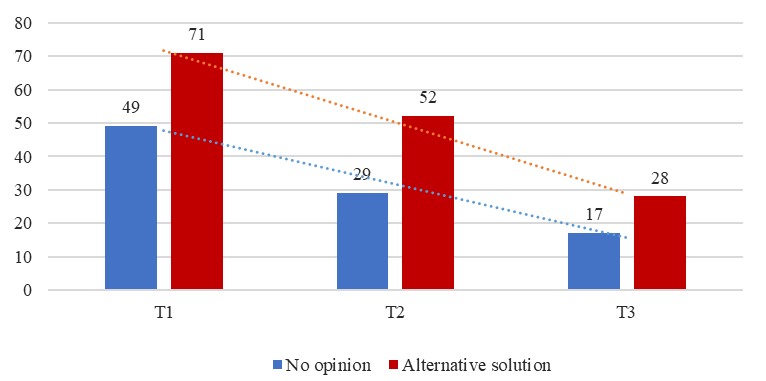

Findings for "Other solutions"

Three main types of "other solutions" were identified during the data analysis:

Type 1 - Unrealistic or imaginary solutions.

Type 2 - Solutions that were actually explanations that the respondent gave for their choice of a predetermined given solution, A or B.

Type 3 - Solutions that are genuinely different from solutions A or B.

"Other solutions" were written by participants at each of the research stages but they became fewer in stage 2 (T2) relative to stage 1 (T1) and then fewer in stage 3 (T3) relative to stage 2 (T2). These solutions mainly stemmed from the participants’ lack of knowledge, emotional difficulty or a desire to express a personal opinion. Most of these solutions were in fact explanations for the choice of solution A or solution B given in the questionnaire and so they actually reinforced the choices of these options from the participant's point of view.

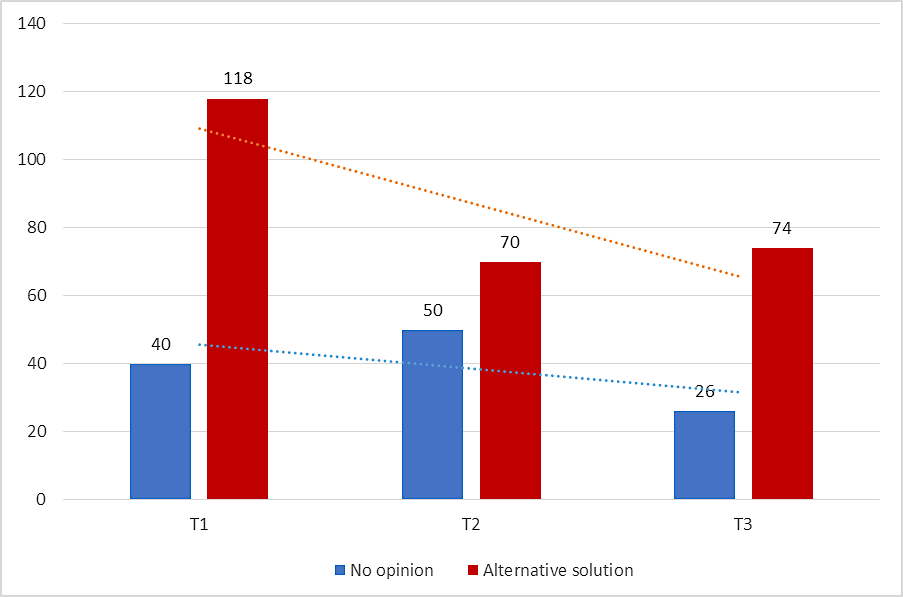

Findings for “I have no opinion” responses

The attitudes questionnaire also gave participants the possibility of choosing the response “I have no opinion” as an option. As can be seen in Table

Conclusion

The results indicate that as the research progressed through the different stages there was a clear decrease both in the number of "Other solution" and “I have no opinion” options that were chosen. The reduction of “I have no opinion” answers can be attributed to an authentic effort by the participants to cope with the dilemmas and the contribution of the learning process and maturation over time. In the dilemmas from the Holocaust era there were more participants who chose the option “I have no opinion” than in the post-Holocaust era dilemmas. This testifies to the greater strength of the dilemmas from Holocaust era and the serious difficulty that participants had to cope with them. It seems that the main reasons to write an "Other solution" were a lack of knowledge (mainly at the beginning of the learning), emotional difficulty and cognitive confusion about the justification for the different given solutions, as well as a will to explain in words the moral choices they had marked in the questionnaire. The conclusion is that the learning process in the Holocaust Learning Program, which provided more knowledge and clarified the issue of Holocaust moral dilemmas, along with maturation processes over time and participants’ motivation reduced the use of both "no opinion" responses and the writing of "other solutions".

References

- Browning, R. C. (2004). The origins of the final solution: The evolution of Nazi Jewish policy, September 1939-March 1942, with contributions by Jurgen Matthaus. University of Nebraska Press; Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, Jerusalem.

- Christensen, J. F., Flexas, A., Calabrese, M., Gut, N. K., & Gomila, A. (2014). Moral judgment reloaded: A moral dilemma validation study. Frontiers in Psychology 5, 607.

- Cushman, F., & Greene, J. D. (2012). Finding faults: How moral dilemmas illuminate cognitive structure. Social Neuroscience, 7, 269–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470 19.2011.614000

- Cushman, F., Young, L., & Hauser, M. (2006). The role of conscious reasoning and intuition in moral judgment: Testing three principles of harm. Psychological Science, 17, 1082–1089. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467- 9280.2006.01834.x

- Farabstein, E. (2002). Hidden in thunder. Philosophy and leadership in the days of the Holocaust. Jerusalem: Rav Kook Institute. [Hebrew]

- Foot, P. (1967). The problem of abortion and the doctrine of double effect. Oxford Review, 5, 5–15

- Goldhagen, D. J. (1998). Hangmen by choice, serving Hitler, ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. Yediot Ahronot and Sifrei Hemed. [Hebrew]

- Graham, J., Nosek, B. A., Haidt, J., Iyer, R., Koleva, S., & Ditto, P. H. (2011). Mapping the moral domain. Journal of personality and social psychology, 101(2), 366. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021847

- Greene, J. D. (2011). Emotion and morality: A tasting menu. Emotion Review, 3(3), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1754073911409629

- Greene, J. D., Nystrom, L. E., Engell, A. D., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2004). The neural bases of cognitive conflict and control in moral judgment. Neuron, 44, 389–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2004. 09.027

- Greene, J. D., Sommerville, R. B., Nystrom, L. E., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science, 293, 2105–2108. https://doi.org/10.1126/sci ence.1062872

- Haidt, J. (2007). The new synthesis in moral psychology. Science, 316, 998–1002.

- Kohlberg, L. (1973). The claim to moral adequacy of a highest stage of moral judgment. Journal of Philosophy, 70, 630-646.

- Koenigs, M., Young, L., Adolphs, R., Tranel, D., Cushman, F., Hauser, M., & Damasio, A. (2007). Damage to the prefrontal cortex increases utilitarian moral judgments. Nature, 446, 908–911. https://doi.org/10.10 38/nature05631

- Starcke, K., Ludwig, A. C., & Brand, M. (2012). Anticipatory stress interferes with utilitarian moral judgment. Judgment and Decision Making, 7(1), 61–68.

- Tassy, S., Oullier, O., Duclos, Y., Coulon, O., Mancini, J., Deruelle, C., & Wicker, B. (2012). Disrupting the right prefrontal cortex alters moral judgment. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7, 282–288.

- Tassy, S., Oullier, O., Mancini, J., & Wicker, B. (2013). Discrepancies between judgment and choice of action in moral dilemmas. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 250.

- Youssef, F. F., Dookeeram, K., Basdeo, V., Francis, E., Doman, M., Mamed, D., & Legall, G. (2012). Stress alters personal moral decision making. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37, 491–498.

- Zimerman, M. (2013). Germans against Germans. The fate of the Jews 1938- 1945. Am Oved Publishers. The Hebrew University in Jerusalem. The R. Kavner Center. [Hebrew]

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 March 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-103-4

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

104

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-536

Subjects

Education, teacher, digital education, teacher education, childhood education, COVID-19, pandemic

Cite this article as:

Efrat, S. (2021). The Evolution of Different Solutions to Holocaust Moral Dilemmas. In I. Albulescu, & N. Stan (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2020, vol 104. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 377-383). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.03.02.39