Abstract

The following paper wishes to assess the degree of satisfaction that adult students have with their private language classes in non-formal education settings and their usefulness on the labour market. It focuses on establishing the main age groups, education level, social status, languages studied and their applications to see how this reflects the role of non-formal education today. The field of non-formal private classes is still developing in Romanian society, becoming more in demand in a global, dynamic market that is constantly changing and requiring new skills. Language classes in particular are seeing a rise in popularity as many foreign companies are now opening headquarters in Romania. The study is based on 100 adults, Romanians who chose to learn foreign languages and foreigners who are learning Romanian, in the city of Cluj-Napoca between 2018 and 2020. The study used a questionnaire given to the subjects at the end of their classes, focusing on their overall satisfaction with the curriculum, workbook, teacher, location, and time, as well as their personal investment in the learning process. The results show that there are some clear trends in the category of people who enrol themselves for such classes, from an educational, professional and age perspective and their needs for the languages. Their further use of the knowledge acquired through these classes also follows certain trends.

Keywords: Adult educationlanguagenon-formalsatisfactionefficient teaching

Introduction

Non-formal education exists in Romania in the form of private classes that offer professional reconversion, technical skills, or foreign languages. In recent years, the number of companies offering language classes has grown, especially in large and medium sized cities, with a growing request for them coming now from smaller cities too. Companies with foreign capital are now present in many cities in Romania and they serve an international market, making communication very important for staying competitive and increasing their profits. They need skilled workers who not only are professionals in their fields but also speak at least two or three languages. Often the level of fluency required is not that of a proficient or academic speaker but enough to communicate politely and efficiently in a business environment. They hire people who already have some language skills but are willing to invest in training their staff through private lessons, to increase the efficiency of their workforce. Given that Romania has the second fastest internet in the world and smaller salaries than other parts of Europe, accompanied by a well skilled workforce, more and more global companies are entering the market.

Due to opening to the global market and the European trading space, Romania has seen not only emigration but, in recent years, immigration, that can be permanent or transitory. Hence, besides the request for foreign languages, there is a new demand for Romanian classes as well. This immigration is seen again mostly in larger cities, because there are more companies there and offer more temporary jobs for non-natives. These companies are willing to offer special language training for the incoming migrants or immigrants, in order to facilitate their integration in Romanian society. They often contact and collaborate with other private companies that offer language classes because these are the only ones that offer such services. Formal education, whether to universities or schools only caters to specific groups of people, namely students and children that are already part of the social structure, but they are seldom or never open to private companies and adults.

The only option left for adults is non-formal education, even though it often offers classes similar to what has been already studied in schools or universities, thus questioning the efficiency and practicality of formal education. The discrepancy between academic training and the needs of the workforce has been much debated in recent years, but no proper reforms have been set in place. The gap that still remains can be filled by non-formal education and sometimes by learning on the job but many companied prefer to look for the services of trained personnel to do the training themselves and recognize diplomas and degrees offered by private firms, especially when they target a specific skill. A formal education degree can often equal a non-formal degree in the eyes of private contractors, who care more about the skills an individual possesses as opposed to what he claims to be possessing. That is why companies and individuals themselves choose to study privately and gain the knowledge and competence that their job requires outside of formal training that seldom fulfil their needs.

The paper will assess 100 individuals who chose language classes, through questionnaires about their identity and degree of satisfaction in order to find the main trends they fit in. They are both Romanians and foreigners, men and women who have contacted private companies for language lessons. The questionnaire aims to establish their educational level, professional background, age, current occupation, individual satisfaction and needs for the classes and see what they reflect about non-formal adult education in a medium sized city in Romania. Big and medium sized cities are the places that offer the most opportunities for non-formal education and have the highest demand for it. Thus, what happens in one of them can reflect the general trend of what happens in most of them, reducing regional differences to the top language requirements. The second and the third part of the article will establish the theoretical background and main research questions and the finding will be explained in detail in the fifth part of the article, followed by some conclusions.

Problem Statement

Non-formal education

Non-formal adult education has certain characteristics that influence the teaching and learning process, especially when it comes to foreign languages, like: short term classes – from a few months to a year (they rarely surpass a year); they take place maximum three times a week, two hours at a time; they take place during working hours or after that; they are individual or in small groups. The subject matter that is to be studied is condensed so that it can be taught in a short time, the teaching method can be adapted to individual needs and progress must be seem already after a few months. Mastering a language is split standardly in several aspects: comprehension, grammar, reading and writing and speaking. Out of these some are easier to condense and teach on a short period of time to an adult student based on how they process information. The easiest to learn are passive comprehension and grammar and the hardest is speaking. Speaking needs more time to become fluent and cannot be condensed.

Adult education has often been non-formal through time, as it aimed either to eliminate illiteracy, develop new work skills, learn a craft, and lately learn now technologies or languages. Its foundation has been the idea that people can continue to develop themselves throughout all their life, regardless of their educational starting point.

Paul Freire represents an important voice in adult education through his democratic visions and the literation methods he developed and successfully used in under-privileged areas in South America. He managed to synthetize in a philosophical way the essence of human communication and its highest purpose – to transcend personal limits by connecting to a universal existence.

The normal condition of man consists not only in being present in the world but be a part of it as well. Man must establish relations with the world and through a game of creation and re-creation that begind with the natural world, he must get to a personal report, a cultural work. In his relations with reality, the sence of reality, man creates a specific means, from subject to object, that results in the knowledge expressed through language. (Freire, 1971, p. 108)

He also raised some controversies, in part due to his idealism and belief in the human capacity to develop oneself in harmony with others and the environment. He presents a philosophical view on education and offers it to common people, regardless of their level, as an instrument for knowledge of the world and themselves. The success he had is not without risk, as his message is always open to personal interpretation and ca be used for manipulation. But it proves to be better fitted for today’s society, so individualistic and dynamic, where independent learning becomes more and more important. However, both in communication and in learning, the individual ca be its own enemy.

The present so-called postmodern time is an era of information and communication, facing technological changes unseen before that influence society and human psychology. Sousa Santos (2003) used another type of characterization to understand the history of education, considering the stage that we are at now. Ancient societies were characterized by a continuity between the experience of the represent and the experience of the future. What is happening in the present will continue into the future: the poor will continue to be poor and illiterate. In developed societies education has become hope for the future. The changes that are taking place will lead to a general progress. In a globalized society most of the population has lost hope, the experience of the present is difficult, and expectations are getting worse. Education is often despised as it is seen out of touch with the times. (Frias, 2009, p. 142)

The despise that the author is talking about is not unfounded as in more and more countries the educational system is following an outdated structure, developed in the industrial era, in which the main objective was the training of qualified workers, specialized in a certain profession that was to be exercised throughout their entire lives. The postmodern period, highly technological and always changing does not require the same type of training as the knowledge gained in a particular class become obsolete in a few years. The new educational targets have been redefined as gaining skills and competences that help people to adapt to a dynamic workforce. This doesn’t seem to have worked as it was expected hence the rise in popularity of private classes and the development of adult education, which can be seen as a consequence of the school system’s failure.

Efficient learning

Human memory is of many types: visual, auditive, kinetic, etc. In the case of language learning the predominant types are visual and auditive and information is stored both morphologically and phonetically. In order to have an efficient learning we must understand more profoundly what is learned phonetically and what morphologically.

The teacher should be capacle of offering the grammatical forms that are similar to the native language, and not let the student just have a guess. We are often surprised when an element from a foreign language is similar to what we have in our native one. Fisiak, Oxford, 1981 p. 3

This changes the way certain linguistic elements are taught. Even though languages are not the same, they all have these two basic aspects. Teaching grammar can especially benefit from learning through morphems and morphemic patterns, that can offer formulas for coding and decoding information, with a minimal use of memory.

To better show the importance of this fact I quote the study

In Semitic languages words can be reduced to their root that is formed of three or four letters, mostly conconants. Vocalisation is made by the speaker and in writing some vowels ca be left out. This means that a great variety of prononciations has aexisted over time and continues to exist and phonetic changes are made easily. It also means that the processing ans storage of the vocabulary is made by the human mind differntly to the phonetic languages. By extension, the research done on these languages can be extended to other non-semitic ones.

In Prunet, Béland, and Idrissi 2000, we presented evidence from an aphasic subject that argued for the morphemic status of Arabic consonantal roots. We predicted that inaudible glides in weak roots should resurface in metathesis and template selection errors, but at the time the relevant data were unattested. Here, we present such data, obtained from a new series of experiments with the same aphasic subject. Arabic hypocoristic formation offers another case of glide resurfacing. Both sources of data confirm that Arabic consonantal roots are abstract morphemic units rather than surface phonetic units. (Idrissi et al., 2008, p. 221)

So, if in Arabic consonantic roots are processed by the human mind as abstract morphemic units and not as superficial phonetic units then the human brain has the capacity to learn certain linguistic particularities as pure abstractions, that it manipulates to create meaning. The fact that this can be directly linked to the roots of the word in Arabic shows that these are the abstract concepts that cognitive linguistics talks about and are thus very practical in teaching.

They can be used to create language families and links between languages for the learners that helps them better understand and remember new information. An approach based on morphemes could be extremely useful when it comes to teaching and learning vocabulary and some grammar features. Through them a teacher can establish grammatical parallels and equivalences between related and non-related languages, making for an intuitive learning experience. Non-formal education is all about fast, effective learning, which actually follows very modern trends in what education in general should be and how it should take place. When it comes to learning languages, nothing beats the ability of children to pick up on whatever they hear around them, but adults can be helped by their teachers to undergo a similar process.

The point of education is to accelerate the acquisition process, not be satisfied with or try to emulate what learners can do on their own. Therefore, what works in untutored language acquisition should not automatically translate into prescriptions and proscriptions for pedagogical practice for all learners. (Bielak & Pawlak, 2013, p. 78)

Through supported learning, formal or non-formal, adults can be helped to acquire the necessary knowledge and abilities to further continue their studies on their own. They tend to be individualistic learners anyway, so they benefit from studying in a small group or one on one setting, where most or all of the teacher’s attention is given to their specific needs and styles. However, outside of such frames, they seldom find the discipline, motivation, and disposition to pursue the study of a new language.

The prointervention positions view pedagogical intervention as having a facilitative function with respect to the acquisition of language and its grammar, or even see it as indispensable. Specifically, they represent the view that although formal instruction may in most cases not be necessary to ensure that learners acquire foreign language grammar, such instruction is able to speed up and generally enhance the process so that higher levels of proficiency are achieved. (Bielak & Pawlak, 2013, p. 100)

When using teaching methods developed around achieving a more efficient learning, the teacher’s input is very important as these are presented and applied through and by him. It is the teacher that can offer a morpheme-based learning system, if the student is not a linguist or philologist himself, which he or she usually isn’t, and it comes to the teacher to present new structure of grammar in an easy and intuitive way. Workbooks can only do so much in this case as a deeper understanding often require a human mediator. The focus of this article was thus on the teacher’s performance and appreciation by their students, along with the books, time, place and structure.

Research Questions

This study was designed to find out who chooses to study foreign languages in non-formal education and what is the degree of satisfaction they have with the new skills acquired through them in order to identify some major trends about their social status, origin and practical needs. It considers several languages that are in high demand on the market, including Romanian for foreigners. Given that all the subjects are adults enrolled in private language classes in a non-formal setting, they are treated the same, regardless of their nationality and origin. The most in demand languages on the private market in the city of Cluj-Napoca are English, Romanian, German, French, Spanish and Italian. Other requested languages although rarely are Russian and Arabic.

The Romanian natives

Language classes are requested by native Romanians who wish to learn a new language or improve one they have studied before, often at the demand of their employers, who also sponsor them. The major demands are for English – although it is the most studied language in schools, German – in the region of Transylvania and Bucharest, French – on the rise after Brexit, Spanish, Italian and very rarely Russian. Although some of these languages are studied in schools it appears that students don’t graduate with a level that is advanced enough to serve their professional needs and seek private lessons as adults. The research wishes to see what are the main social groups that these people belong to, from an educational and professional perspective in order to better understand their needs, the faults in their formal education and the role of non-formal education in their career advancement.

Other nationals

The demand for Romanian classes has increased in recent years as foreign companies that open headquarters in Romania are willing to relocate highly skilled people to Romania for a time. This has led to a rising demand for Romanian as a foreign language classes but also for secondary languages like German or French. As the companies pay for the training and offer it as a relocation package, often the families of the temporary immigrant benefit from them. The request for other languages beside Romanian comes from them. However, their choice to enrol in private language classes is based on similar needs as the Romanians and follow the same trends. The gap between academic training and workforce requirement seems to exist in other countries as well.

Purpose of the Study

As stated before, the purpose of this study is to discover the major social and economic categories of people who choose language classes in non-formal education and their degree of satisfaction with their training and try to find the connections between them and the present job market in a globalized world. It also aims to identify the role that non-formal education plays in filling the gap between academic studies and workforce requirements and the importance of teaching in the learning process.

Research Methods

The research method is a small N survey, with questionnaires that I have developed myself as the instruments. The questionnaires are designed to discover the degree of satisfaction of the people who study languages, by identifying certain things about the social status of the people involved, like age, gender, ethnicity, education level, profession, and their individual need for classes. Their needs range from professional obligations to social needs to personal interest to emigration. This study is exploratory and not confirmatory.

The choice of respondents was mostly influenced by feasibility issues as the study was done through a collaboration with a private language company in Cluj-Napoca, but they consist of both men and women, Romanians, and foreigners, of all ages. They were given the questionnaire at the end of their classes, so it had to be easy to fill in and not take too much of their time. I have chosen questionnaires instead of interviews because they allow a generalization of major trends and offer closed answer questions, with the benefits that the results are standardized easier and get a synthetic analysis. Interviews would have been difficult to do in a private setting as the respondents do not want to waste too much of their time doing something unrelated to the studies that they are paying for, so very few would have agreed to more that filling out a questionnaire. This is more of a pilot study of a new area in education in Romania and the rather small sampling is supposed to identify the major trends that can be further explored in the future. The questionnaire has two main parts, the first one made up of nine choices, designed to assess the subjects social background, educational level, profession, age, gender and studied language and the second one, made up of five closed questions aiming to establish the more personal factors of general satisfaction. The questions are how satisfied they are with the progress they have made during the course, whether the competences gained are enough for their needs, how they intend to apply what they have learned, how involved they have been in the learning process and how many hours per week they have studied. Each question is followed by a list of statements to which the subject can agree, partially agree or disagree. The questionnaire itself can be found at the end as an appendix A.

Findings

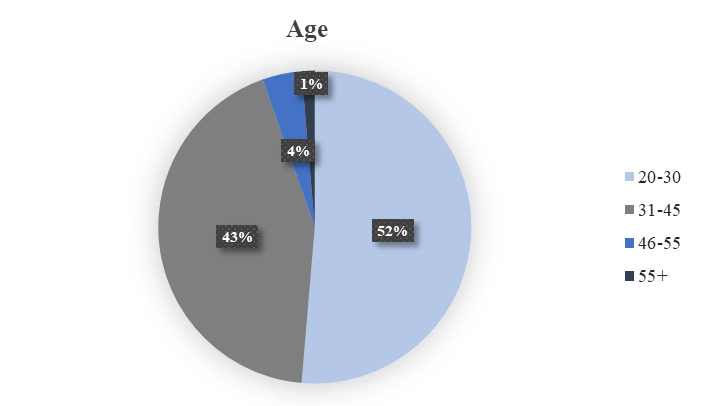

The questionnaires were given to 100 people aged 20 to 70, who all attended private language classes, 57 men and 43 women, 60 Romanians and 40 non-Romanians of many nationalities. Of them 52 were between the ages 20 to 30, 43 were between the ages 31 to 45, 5 were between the ages 46 to 55.

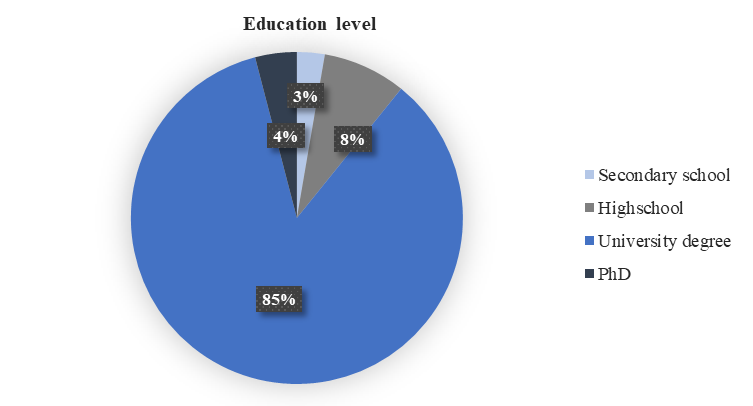

Of all the subjects 85 had a university degree, 14 had a high school degree, 1 had a PhD; 50 worked in a technical field, 15 in an economical field, 15 in a corporate field, 10 in design, 3 in a medical field, 2 in Law, 5 in an executive field. 80 of them were currently employed, 10 owned their own business, 2 were homemakers, 3 were unemployed, 4 were students and 1 was retired. 73 had some knowledge of English, 36 of German and 15 of French.

Already from the more general questions, some clear trends appear, no matter what the ethnicity of the subjects. The biggest age group choosing to study foreign languages privately are between the ages 20 to 30, followed closely by the 31 to 45 age group. Few people above 45 seem interested in linguistic non-formal education. (Figure

Most people have a university degree and are currently employed, either in a technical, economic, corporate, or creative field (Figure

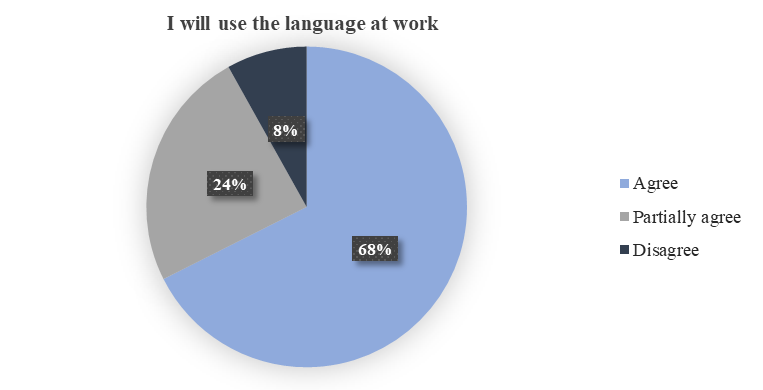

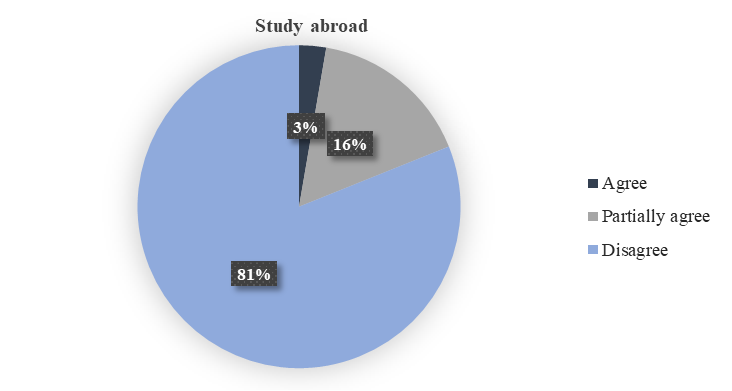

60 of them want to perfect an already known language, 68 want to learn an international language, 68 see it as a possibility for career advancement, only 22 would like to change their current job, 82 have some sort of professional obligation to learn the language, only 19 would like to emigrate, only 18 have family or social obligations to learn the language, only 18 want to study abroad, 83 claim an interest in the language, 90 want to speak the language fluently, 76 see it as a way to get along with their community, 88 see it as a way to communicate professionally, 43 see it as a way to a better job, 84 hope to get some personal satisfaction out of it. 58 claim they will make a considerable effort to learn, 60 will learn as much as their time allows them, 52 hope to learn only by attending the class, 41 claim to allocate 1-3 hours a week for learning and 34, 3-5 hours a week.

As it can be seen from the more personal questions, the main motivation of studying a foreign language seems to be related to the professional field, whether it is required for the job itself or it is a plus in the long term, followed by a desire to fit into the community, as seen in Figure

The split between men and women is almost equal, but some of the unemployed housekeepers mentioned are part of the female group, making men more interested in private classes than women due to their professional status. Most people expect to learn the new language by attending the class and with very little individual effort at home, which can be due to the lack of free time, family demands and interest that is more connected to practical necessities. Adult students are already formed as a personality, so they don’t view their continuation of studies as a part of their continuous formation as people and more as a plus for their formation as professionals. The language classes are considered part of their work and not of their pleasure and represent more time spent for their jobs so at home they prefer to focus on other things.

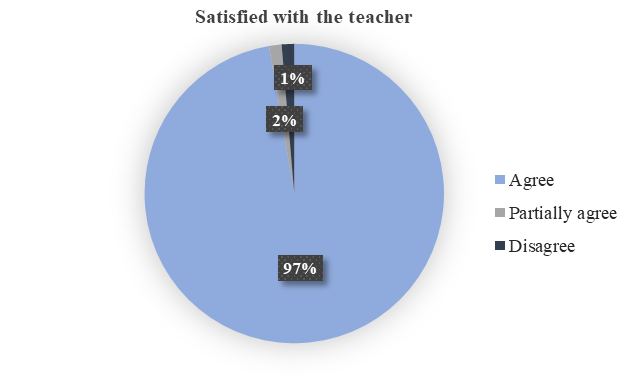

There appears to be a good level of satisfaction with the non-formal studies, both when it comes to teaching methods and to the place and workbooks (Figure

These are the main trends that can be found both with Romanians and foreigners studying language classes in Cluj-Napoca in the year 2018-2020. Further I have divided the two in order to see what is different between the groups.

Romanians

The assessment showed that the Romanians who chose to study foreign languages in non-formal education were more women than men, although it depends on the studied language. The main languages demanded were English and German, followed not so closely by French and Spanish. Russian is a rarity. The German need can be explained by the presence of many German companies in Transylvania and Cluj-Napoca, where the study is based, specialized in technical manufacturing or services. Also, more men chose German classes than women and were working in a technical field. As for English, even though it is studied in schools for as much as twelve years, it appears that the level achieved by the students is not advanced enough for the demands of a global job market. This points to deficits in the formal education received at school, which, despite its lengthy duration, does not offer enough to cover for the real necessities of the job market, leaving graduates without proper training. Women are more present in English, French, Spanish and Italian classes, and work in corporate or economical fields. The main age categories are 20 to 30 years, followed by 31 to 45 years, with few students over 45 years old and only one over 55. About 90 % have a university degree, some even a PhD and were employed during the study or had their own business. They work in technical fields, followed by corporate and economical.

A great majority are satisfied with their classes, their teachers, workbooks, the place and time of the lessons. These types of classes take place either at the company where the students work or at the office of the company that offers them. The teachers are freelancers and collaborators and less so employees, who have some pedagogical training or learn from their reaching experiences. Due to the lack of a curriculum or finality of the studies through an exam, there is greater freedom to use whichever method is required and works better and to follow the rhythm of the students rather than impose one. As most people apply for these classes for work related reasons and not for studies of emigration, very few of them are preparing for an international language exam like IELTS or Cambridge (Figure

One can also argue that the participants who have studied abroad at one time in their lives had already mastered a foreign language to a satisfactory degree before they went there or had gained more knowledge whilst there and do not need to take up private lessons later in life. Also, the older students that request private lessons, that is, past the age of 50, are usually not Romanian but foreign. It appears that Romanians belonging to older generations are not interested in non-formal education, which is logical as it is a new field in education in Romania or if they do, they just find private tutors who go to their homes.

The very young students, children or minors and the elderly tend to choose more traditional non-formal education settings like private tutoring at home. The young adults and mature adults seem to prefer a more organized setting, within a group or alone but structured into study modules that cover specific language levels so that at the ends they can have some idea as to how well they know the language.

Foreigners

The non-Romanians who chose to study Romanian in a non-formal private setting came from many different national backgrounds, with no country being represented predominantly. However, the gender division is different to that of the natives, with an 80 % to 20 % ration of men to women, namely, a greater part of transitory of permanent immigrants were male. Most of them are between the ages 31-45 followed by 20-31 and have a university degree. Foreigners are better represented in the older age group, that is past 50, as most older students that request non-formal language classes are not Romanian.

Foreigners also seem to be quite satisfied with the teaching, workbook, place, and time of the lessons and intend to take several modules of study. That is because they mostly learn Romanian as a foreign language, and they have never studied it before. Other languages that are requested by this group, albeit very rarely, are French and Russian. Their main reasons for studying Romanian are integration in the community and being able to get by daily. If they intend to settle here then they are interested in reaching a more advanced level and are more dedicated to their studies, which can last for up to 2 years, a rather long time for non-formal education. It is with them that we see the elderly group of people better represented, with ages between 50 and 70 years old. Some of them are retired and choose to study a foreign language out of interest or to break the monotony of their daily lives.

Another group appearing here are expat housemakers, the wives of the men who came to Romania for their careers and who are usually transitory and do not wish to settle. This group chooses Romanian and other languages for fun and socializing, prefer a one-on-one approach and befriend their teachers. They also get private home classes if the teacher agrees to it.

This reflects the custom that the family follows the husband as the traditional income earner wherever his career takes him so relocating is more often because of the husband’s job and not the wife’s, especially if they have children. The men usually have higher positions at work and better salaries.

As the languages that foreigner’s study are not mandatory for their work, they tend to be more demanding and ask for a change of teacher more often if they don’t get along. They don’t intend to learn by themselves as they are very busy if employed and see the lessons as a leisure activity, not to be taken too seriously.

Conclusion

Through this study I set up to discover the main trends in adults who choose language classes in a non-formal setting in a medium city in Romania, taking Cluj-Napoca as an example. Cluj-Napoca is representative for an Eastern European middle to large city, that is in a stage of expansion and development and has opened to a global market. Cities of the same region and size have many similarities and are the main centres of non-formal education facilities. The study made here can be considered a sample for the growing social role of adult private education.

The major trends in adult education focused on language learning reveal that the majority of people who choose private classes, regardless of their ethnicity, belong to the age category of 20 to 30 years old, followed closely by a 31 to 45 years old category, have a university degree, are already employed, tend to be more women than men in the case of Romanians and more men in the case of foreigners, they work in technical, economical and corporate fields, and will use their newly gained competences in their profession and at work. Their companies and themselves are willing to pay for private lessons but hope to learn the new language mostly during classes and not so much through individual effort at home, because their main interest in continuous education is professional in nature.

Romanians view their studies as part of their work or connected to work obligations and less as something they would pursue themselves if not obligated. They choose their studied language depending on the company and its requirements rather than personal taste. Rarely do they pursue getting an international degree in said language and are not interested in emigrating or studying abroad. Most of them are between 20 and 45 years old.

The foreigners who come to Romania want to learn Romanian to be better integrated in the local community and to be able to communication on the street or if they are homemakers, for fun and socializing. They tend to be more men as their families are more willing to relocate for the sake of their careers than in the case of women. They also have higher positions at work. Some of them are over 50 years old, up to 70, in a greater percentage than Romanians.

The limitations of this study are due to the relatively small sample of subjects analysed so far, that reflect the bigger trends and the fact that the questionnaires used have set answers, whereas interviews would have yielded more detailed results. The study could benefit in the future by expanding the number of subjects in order to see how trends evolve and change. The same type of study could also be done in other cities in Romania and Eastern Europe to see how the situation there compares to that in Cluj-Napoca, in terms of similarities and possible differences.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the company Linguastar, based in Cluj-Napoca that I collaborated with for allowing me to do this study and facilitating my work.

References

- Bielak, J., & Pawlak, M. (2013). Applying Cognitive Grammar in the Foreign Language Classroom. Springer.

- Fisiak, J. (1981). Contrastive linguistics and the language teacher. Pergamos Press.

- Freire, P. (1971). L’education: pratique de la liberte [Education: practice of freedom]. Les editions du cerf.

- Frias, R. J. (2009). Education de personas adultas en el marco del aprendisaje a lo largo de la vida [The education of adults in the framework of lifelong learning]. UNED.

- Idrissi, A., Prunet, J.-F., & Belard, R. (2008). On the Mental Representation of Arabic Roots. Linguistic Inquiry, 39(2), 221-259.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 March 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-103-4

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

104

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-536

Subjects

Education, teacher, digital education, teacher education, childhood education, COVID-19, pandemic

Cite this article as:

Onutz, T. (2021). Student Satisfaction And Usefulness Of Language Classes In Non-Formal Education. In I. Albulescu, & N. Stan (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2020, vol 104. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 345-359). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.03.02.36