Abstract

Well-being is vital for the optimal functioning of students in universities. The present study aimed, on the one hand, the analysis of the subjective well-being of a group of students and, on the other, to test the structure of subjective well-being in the case of the same sample students (N = 516; Mage = 20,09). To this purpose, we used scales that measure both the cognitive and affective components of the subjective well-being: Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) which takes into account the individual's satisfaction regarding his own life and Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE) for measuring positive and negative feelings and experiences. Descriptive analysis and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were used as statistical strategies. The results show medium to high values of life satisfaction, positive and negative affect. Female subjects report negative affective states in a higher degree compared to male subjects. Regarding the structure of the subjective well-being, CFA leads to a three-factors model that proves the premise that subjective well-being is a multidimensional construct that includes life satisfaction, positive affect and negative affect (χ² = 2,53; CFI = .95; RMSEA = .055; SRMR = .048). The result, also, demonstrates that the three components of subjective well-being, satisfaction with life, positive affect and negative affect, are relatively independent and moderately correlated. Further studies are needed to verify the subjective well-being structure on other peoples categories and to include other well-being components in its structural analysis.

Keywords: Subjective well-being structurepositive affectnegative affectlife satisfactionstudents

Introduction

There are two directions of research on well-being in the studies of positive psychology: the

Problem Statement

Subjective well-being (SWB) is essential for mental health at young age and is a determinant of many life outcomes (Suldo et al., 2011). The main dimensions of SWB in youth are related to the balance between experiencing positive emotions (e.g., happiness, optimism) and negative emotions (e.g., anxiety) and life satisfaction (Diener et al., 1999; Proctor et al., 2009). There is a controversy over the structure of subjective well-being with regard to the way in which its components relate to one another: are they distinct components or are they ramifications of one and the same concept? For example, some studies showed that the positive and the negative affect are separable components rather than two poles of the same continuum (Schimmack, 2008; Joshanloo, & Bakhshi, 2016). On the other hand, some pieces of research have shown moderated correlations between the cognitive and the affective variables of SWB (Arthaud-Day et al., 2005; Diener et al., 1995; Galinha & Pais-Ribeiro, 2008). And again, there are studies which did not find any correlations between the mentioned variables, or they found some that are very weak (Galinha & Pais-Ribeiro, 2008; Balatsky & Diener, 1993). For example, Albuquerque et al. (2012) used instruments such as Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) and Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) in the case of a sample of Portuguese teachers and they reached the conclusion that SWB has three elements: life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect, which are moderately correlated and relatively independent. Suar et al. (2019) analyzed four components of SWB: life satisfaction (LS), positive affect (PA), and negative affect (NA) and flourishing, and concluded that the best way to account for the structure of SWB is to consider the hierarchical structure with the interdependence of the four components. Their results corroborated the results of Busseri (2018) who meta-analyzed the correlation between positive affect, negative affect and life satisfaction and concluded that the three components have substantial loading on a latent SWB factor. Thus, the results support the generalization of the association between positive affect, negative affect and life satisfaction within SWB (Busseri, 2018).

Research Questions

In the subjective well-being composition, life satisfaction, positive affect and negative affect are correlated but independent constructs?

Purpose of the Study

We have proposed to analyse the subjective well-being of a group of students and secondly to examine the structure of SWB in the case of the sample of students by using two scales: one specific to the measurement of the cognitive component and another one for the affective one.

Research Methods

Participants and procedure

516 undergraduates (306 males and 210 females) who study in different public universities in the economic (35%), technical (60%), and mathematical domain (15%), in the 19 to 28 age bracket (M = 20,09; S.D. = 1,20). The instruments were administered in groups during the teaching activities from the 2018 – 2019 academic year and each administration was completed in about 7-8 minutes. The subjects provided informed consent and completed the measures without being rewarded for their participation in the study.

Data Collection Instruments

Satisfaction with Life Scale – SWLS (Diener et al., 1985) is a 7-point Likert style response scale which takes into account cognitive appreciation of life satisfaction. Sample item:

Scale of Positive and Negative Experience – SPANE (Diener et al., 2010) assess a broad range of pleasant and unpleasant feelings by asking people to report their feelings in terms of their duration after recalling their activities and experiences during the previous 4 weeks. The SPANE consists of 12 items: six items assess positive feelings (Spane-P subscale), and the other six assess negative feelings (Spane-N subscale) on a scale from 1 to 5. Finally, affect balance is also calculated (Spane-B): the negative feelings score is subtracted from the positive feelings score. Cronbach’s alpha varies between .89 – .92 (Li et al., 2013). In our sample, the internal consistency coefficients are between .80 (Spane-P) and .77 (Spane-N) and confirmatory factor analysis shows good model fit:

Data analysis

Data analysis were conducted using SPSS 22 and Amos 20 and consisted of descriptive statistics and structural equation modeling, specifically CFA for SWB structure verification.

Findings

The three variables which are believed to interact are life satisfaction, positive affect and negative affect, and they cover the cognitive and affective dimension of SWB. Tables

According to the standards proposed by Diener et al. (1985) who find in the case of undegraduates an average of life satisfaction of 23,50 (S.D. = 6,43), and by Pavot and Diener (1993) (M = 23,7; S.D. = 6,4), the average values obtained by the group of students show that they have average to high scores on life satisfaction. It can be considered that the respective students are generally satisfied, but have some areas where they would very much like some improvement (M. life satisfaction total score = 24,70; S.D. = 5,55).

The averages obtained in the case of life satisfaction were compared with those obtained by other studies on Romanian students (Marian, 2007); the comparison revealed similarities with regard to life satisfaction, with slight increases in the present case for items 2 (The conditions of my life are excellent – M = 5,11/1,28), 3 (I am satisfied with my life – M = 5,30/1,36), and 4 (So far I have gotten the important things I want in life – M = 5,42/1,48) of life satisfaction total score (SWLS), which refer to the global assessment of satisfaction with life.

In the case of SPANE, average levels are observed for both PA and NA, compared to SPANE scale norms in terms of percentile rankings (Diener et al., 2010). The items that register high average values are the following: happiness, (M = 3,92 / .91), joy (M = 3,88 / .86), general well-being (M = 3,95 / .81) (Spane-P) and there is only one item from the Spane-N scale that had the highest score, in the case of the analyzed group, in the last month, namely, general condition bad (M = 3,95 / 0.81).

Regarding the gender difference, the t test is statistically significant (t = -2,52; p = .012) only at the SPANE-N subscale (M males = 14,99 / 4,41; M females = 15,99 / 4,38) which indicates higher negative emotional feelings in the case of women. To this result contribute, in particular, the self-reported states of fear of female subjects at a higher level than male students (M males = 2,27 / 1,18; M females = 2,81 / 1,29) (t = -4,84; p = .000). The result is consistent with research showing that women have more negative emotional feelings than men (Chukwuorji & Nwonyi, 2014; Li et al., 2013).

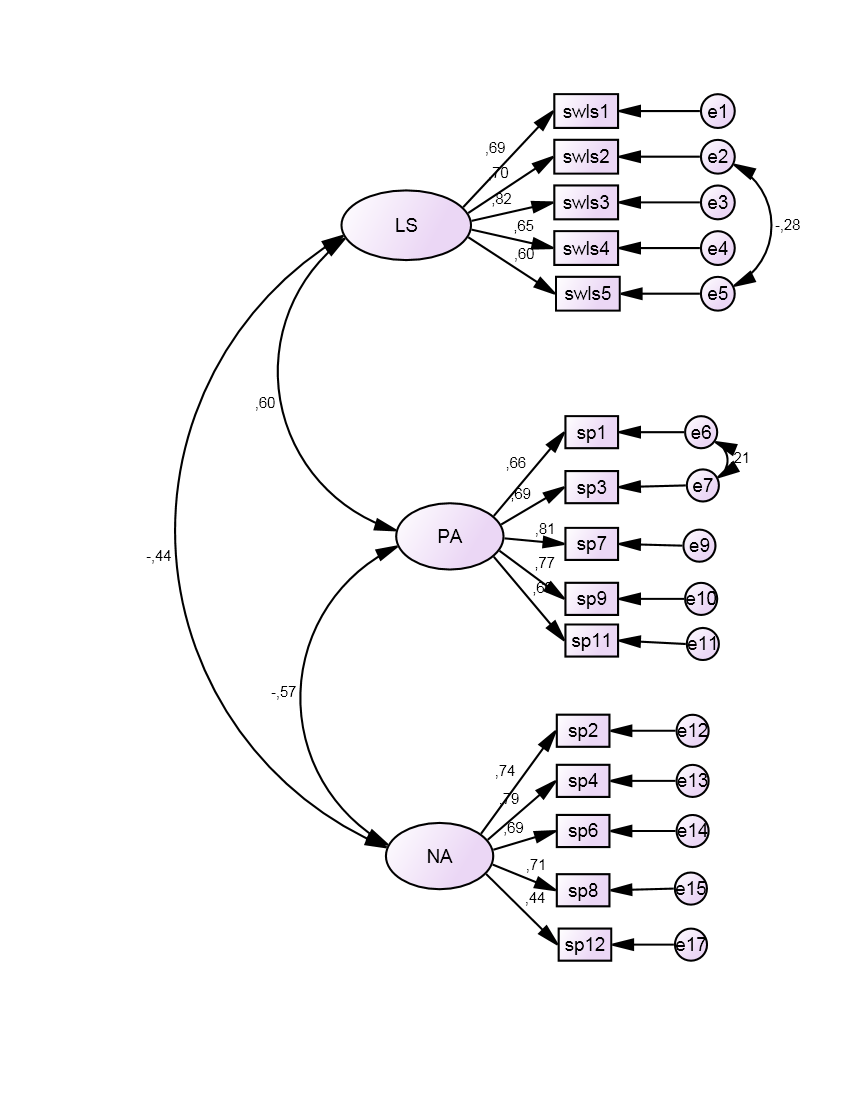

In the next step, we resorted to the confirmatory factorial analysis (CFA) in which the three variables assessed by means of the used scales were included: life satisfaction, positive affect and negative affect, and thus, a number of 17 items were incorporated. For the evaluation of the model the following indexes were examined: χ² value, df, χ²/df (CMIN), GFI (goodness-of-fit index), AGFI (adjusted goodness-of-fit index), PGFI (parsimony of goodness-of-fit index), CFI (comparative fit index), RMSEA (root mean squared error of approximation), SRMR (standardized root mean square residual).

Due to the weak loading (under .40), item 5 (

As figure

The correlation between life satisfaction and positive affect is a moderate one (.60), and life satisfaction and negative affect (-.44), as well as positive affect and negative affect (-.57), show reverse correlations. The correlation between positive affect and negative affect is close to the one reported on by Diener et al. (2010) (see figure

Conclusions

The aim of the study was to identify and analyze the well-being level in the case of a group of students and to examine the structure underlying the three components of SWB by CFA.

The results show moderate levels of life satisfaction, PA and NA for the analyzed group and the fact that the students record higher scores on negative affectivity compared to the male participants. Secondly, the study identifies the three factors of the model that account for SWB and it corroborates the relative independence of affective and cognitive components discovered in other studies (Albuquerque et al., 2012).

The research identifies a model with three factors that are independent, but moderately correlated, which account for SWB. 94% of the items included in the model have a strong factor loading. In addition, the reliability of the subscales that make up the model is acceptable (.78 for SWLS, .80 for SPANE-P, and .77 for SPANE-N). Unlike other studies which have found a weak correlation between the above-mentioned components (Sumi, 2014), the present study showed the moderate correlation between the above-mentioned components and it demonstrated the relative independence of the cognitive and the affective components of SWB; this conclusion corroborates the conclusion of other studies (Albuquerque et al., 2012; Arthaud-Day et al., 2005; Diener et al., 2010; Li et al., 2013). As for the correlation between the affective dimensions of SWB, the results in the present study show that these components, namely positive affect and negative affect, are separable and reversely correlated. Just like the studies that used PANAS scale in the examination of structure SWB (Albuquerque et al., 2012), the present one confirmed that positive affect and negative affect are not completely independent, but they are moderately and reversely correlated. In addition, the results show that the Romanian versions of Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) and Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE) are significant instruments in the assessment of life satisfaction and SWB in the case of students if items 5 (pleasant) and 10 (afraid) within SPANE, which have very weak loading, are eliminated.

References

- Albuquerque, I., Pedroso de Lima, M., Figueiredo, C., & Matos, M. (2012). Subjective well-being structure: Confirmatory factor analysis in a teachers’ Portuguese sample. Social Indicator Research, 105(3), 569-580.

- Arthaud-Day, M., Rode, J., Mooney, C., & Near, J. (2005). The subjective well-being construct: a test of its convergent, discriminant, and factorial validity. Social Indicator Research, 74, 445-476.

- Balatsky, G., & Diener, E. (1993). Subjective well-being among Russian students. Social Indicator Research, 28, 225-243.

- Busseri, M. A. (2018). Examining the structure of subjective well-being through meta-analysis of the associations among positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 122(1), 68-71.

- Chukwuorji, J. B., & Nwonyi, S. K. (2014). Test anxiety: Contributions of gender, parent's educational level and self-esteem among secondary school students. International Journal of Communication, 15(1), 97-115. https://oer.unn.edu.ng/read/test-anxiety-contributions-of-gender-parents-educational-level-and-self-esteem-among-secondary-school-students-vol-15-no-1-2014

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71-75.

- Diener, E., Smith, H., & Fujita, F. (1995). The personality structure of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 130-141.

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276-302.

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New measures of well-being: Flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicator Research, 39, 247-266. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2354-4 12

- Galinha, I. C., & Pais-Ribeiro, J. (2008). The structure and stability of subjective well-being: a structure equation modelling analysis. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 3, 293-314.

- Joshanloo, M., & Bakhshi, A. (2016). The factor structure and measurement invariance of positive and negative affect: A study in Iran and the USA. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 32(4), 265-272.

- Li, F., Bai, X., & Wang, Y. (2013). The Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE): Psychometric Properties and Normative Data in a Large Chinese Sample, PLoS ONE, 8(4), e61137.

- Marcu, R. (2013). New psychometrical data on the efficiency of Satisfaction with Life Scale in Romania. Journal of Psychological and Educational Research, 21(1), 77-90.

- Marian, M. (2007). Validarea Scalei de Satisfacţie cu Viaţa: caracteristici psihometrice [Validation of the Satisfaction with Life Scale. Psychometric characteristics]. Analele Universităţii Oradea, Fascicula Psihologie, XI, 58-70.

- Pavot, W. G., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the Satisfaction with Life Scale. Psychological Assessment, 5, 164-172.

- Proctor, C. L., Linley, P. A., & Maltby, J. (2009). Youth life satisfaction: A review of the literature. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 10(5), 583–630.

- Suar, D., Jha, A. K., Das, S. S., & Alat, P. (2019). The structure and predictors of subjective well-being among millennials in India, Cogent Psychology, 6(1), 1-17.

- Suldo, S. M., Huebner, E. S., Savage, J., & Thalji, A. (2011). Promoting subjective well-being. In M. A. Rray & T. J. Kehle (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of social psychology (pp. 504-522). Oxford University Press.

- Sumi, K. (2014). Reliability and validity of Japanese versions of the Flourishing Scale and the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience, Social Indicator Research, 118(2), 601-615.

- Schimmack, U. (2008). The structure of subjective well-being. In M. Eid, & R. J. Larsen (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being (pp. 97-123). Guilford.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 March 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-103-4

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

104

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-536

Subjects

Education, teacher, digital education, teacher education, childhood education, COVID-19, pandemic

Cite this article as:

Balgiu, B. A. (2021). Examining The Subjective Well-Being In A Students’ Sample: Characteristics And Structure. In I. Albulescu, & N. Stan (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2020, vol 104. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 288-295). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.03.02.31