Abstract

There are discussions in the scientific world about whether or not there are real differences between generations. But people perceive each other based on generational affiliation. Therefore, the purpose of this work was to study the correlation between the perception of intergenerational relations and the frequency of interaction with different generations. The survey was conducted to confirm the hypothesis that the frequency of contacts with different generations is related to the perception of intergenerational relations. 134 people between the ages of 17 and 65 took part in the survey. The results of the study showed that the frequency of contacts with the Soviet generation positive correlates with the positivity of perception of relations with the Soviet generation and negative correlates with the positivity of perception of relations with the post-Soviet generation. The frequency of contacts with the transition generation positive correlates with the positivity of perception of relations with the transition generation and negative correlates with the positivity of perception of the relations with the Soviet generation. The frequency of contacts with the post-Soviet generation positive correlates with the positivity of the perception of relations with the post-Soviet generation and negative correlates with the perception of the relations with others generations.

Keywords: Generational stereotypesintergenerational relationspost-Soviet generationSoviet generationsocial categorizationtransitional generation

Introduction

The issue of intergenerational relations is of particular relevance in the context of worsening geopolitical, economic and social crises. It is in difficult conditions for the society that demographic asymmetry of society is most acute (Fisher, 2020) and strengthening of intergenerational gap (Easthope et al., 2017; Lauterbach & De Vries, 2020; Quadir et al., 2019). They lead to changes in interpersonal relations between representatives of different social groups (Sivrikova, Moiseeva et al., 2019). An important element of these relationships is the interpersonal perception (Sivrikova, Moiseeva et al., 2019), which is formed by culture (Hamamura et al., 2020).

Researchers note that there are currently changes in culture that lead to changes in psychological processes (Kashima et al., 2019). Hamamura, Johnson and Stankovic note that studies describing temporal changes of mores, values, and behaviors are published worldwide (Hamamura et al., 2020). These changes are taking place so rapidly that they lead to the formation of a multigenerational society, that is, a society in which several generations live side by side (Sivrikova, Moiseeva et al., 2019). In science, there is a theory of generations (Sivrikova, 2015), and in the life of people belonging to a generation acts as an indicator of the presence of certain features of personality. And the statements about personality features common in society are not always based on real differences between people of different ages. In particular, the results of the meta-analysis of studies on the level of narcissism in people of different ages did not confirm the hypothesis that this personality trait is more typical for young generation pre-students than for older generation in Australia and Canada (Hamamura et al., 2020).

There is a suggestion that intergenerational perceptions and expectations are likely to develop in society due to increased attention to generations and as a result of the pervasive public discourse associated with generational differences in general and in the workplace in particular (Perry et al., 2017). Furthermore, closer attention to generations and intergenerational differences today probably makes membership in each generation valuable and meaningful. As a result, it can be assumed that intergenerational stereotypes that influence intergenerational relations will be formed in society.

In our study, we turned to an analysis of the correlation between generational perception and frequent interaction with its representatives.

Problem Statement

There are unjustified inequalities in the social sciences. Researchers often turn to analyze age stereotypes and rarely raise the issue of generational perception. Of course, the content of age and generational stereotypes is the same but may differ significantly. This is because of the tog that age and belonging to a generation is not always identical (Lyons & Schweitzer, 2017; Perry et al., 2017). In addition, there are differences between age and generational groups (Sivrikova, Moiseeva et al., 2019). For example, belonging to a generation is constant and belonging to an age group is temporary. The type of generation is related to the national-historical context (different generations are allocated in different countries), and age groups do not depend on nationality and historical events (coincide in different countries).

The field of research on age stereotypes is very extensive. Researchers analyze: the content of age stereotypes in media and online humor (Nimrod & Berdychevsky, 2018), impact on the perception of older persons of experience with them (Bocksnick & Dyck, 2018) and special programs (Lou & Dai, 2017), impact of age on the assessment of victims and perpetrators (Chu & Grühn, 2018), impact of culture on age stereotypes (Schloegel et al., 2018). Comparison of research results will allow detecting contradictions related to age stereotypes: in society, there is an increase in real negative age stereotypes (Levy, 2017; Spangenberg et al., 2018) despite the positive representation of older people in the media (Bae et al., 2018; Oró-Piqueras & Marques, 2017); The ambivalence of age stereotypes (a higher rating of friendliness against the background of low ratings of competence in older persons, and a reverse picture in young people) (Vauclair et al., 2017). The effects of age stereotypes are studied. They are internalization and dissociation (Nimrod, & Berdychevsky, 2018).

Researchers have found that there are differences between the perception of age and generational groups. For example, it turned out that the perception of the "baby boomers" generation was more positive than that of the appropriate age group (Perry et al., 2017). Furthermore, differences in intergenerational perception have been found to be significantly superior to actual differences between them (Sivrikova, Postnikova et al., 2019).

Scientists have obtained indirect data on how people from different generations are perceived in society. But their conclusions are limited conceptually and methodologically, as the subject of these studies were not differences in generational perception in itself (Perry et al., 2017). Study of the content of stereotypes of different generations allowed to find that "baby boomers" are perceived as hard-working and low-component in modern technologies, "millennials" and representatives of generation Y – as naughty but confident in the technology (Sivrikova, Moiseeva et al., 2019).

Researchers conclude that generational stereotypes have a systematic impact on human activity, play a key role in the perception of different generational groups. They may impede communication, trust, knowledge sharing and coordination in joint activities (Schloegel et al., 2018) аnd depend on intergenerational contacts, legislation and social climate (Levy, 2017).

Research Questions

In Russia, interest in the peculiarities of perception of different generations has not been developed in the form of empirical research, but the problem of intergenerational relations in the family is widely discussed (Pishchik et al., 2016; Soldatova & Rasskazova, 2016; Steinbach & Hank, 2016). Little attention is paid to the analysis of the peculiarities of perception of different generations in Russia outside the family context. They are analyzed only in individual works (Sivrikova, Moiseeva et al., 2019).

However, foreign researchers note that social stereotypes and biases are related to social categorization and social identity (Schulz et al., 2020). Hence, social identity theory can act as a theoretical basis for investigating the perception of intergenerational relationships. At the heart of theories of social identity and social categorization is the idea that a person has a need for a positive social identity. As a result, if a particular group membership becomes meaningful, a person has a desire to achieve, maintain, or enhance the positive value associated with that group membership. It is this desire that leads to more positive assessments of its generation and more negative assessments of its other generation (Sivrikova, Moiseeva et al., 2019). This is how biases and stereotypes in the perception of different social groups are born. We have suggested that they also extend to the perception of relations with representatives of these groups.

This study examines the features of intergenerational relationship perception. From the point of view of social categorization theory, the more often and closer a person interacts with representatives of a certain social group, the more he tends to refer to himself in this group. Therefore, the hypothesis of the study was that the frequency of interaction with different generations will influence the perception of relations with these generations.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study was to identify correlations between the perception of intergenerational relationships and the frequency of intergenerational interaction.

Research Methods

At the heart of the methodology of research is the concept of the mentality of generations Pozhik (Pishchik et al., 2016). Therefore, 3 generations were taken for the study, which actually exists in modern Russia: Soviet, transitional and post-Soviet. The allocation of generations, in this case, was based on the most significant event in the history of Russia – the collapse of the USSR.

Participants

134 people took part in the study. Of these, 67 are men and 67 are women. The age of respondents ranged from 17 to 65 years. Employees of enterprises and students of state universities of Chelyabinsk (Russia) took part in the study.

Measures

To evaluate intergenerational relationships, study participants were offered 6 semantic scales (comfort/discomfort; proximity/distance; conflict/absence of conflict; respect/disrespect; misunderstanding/understanding; tranquility/tension). The dimension of the scales ranged from 3 to –3 points. For each of the scales, respondents assessed the relationship of their generation with representatives of different generations: Soviet, transitional and post-Soviet.

The author 's graphic technique was used to estimate the frequency of interaction with representatives of different generations. The study participants were asked to divide the circle (symbol of the circle of communication) into sectors according to how much of the people they communicate with are occupied by each generation. In the processing of results, the size of the sector was converted to a percentage of the whole circle.

Data analysis

A Pearson's correlationanalysis was used to mathematically process the results of the study. Calculations were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23.

Findings

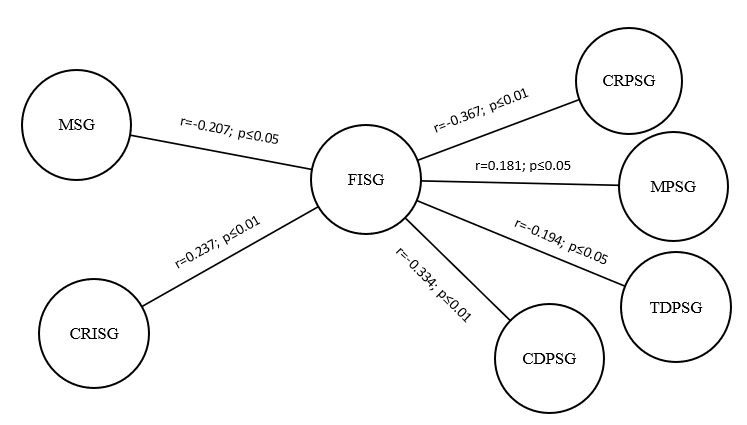

Correlations between the level of contact with the Soviet generation and the peculiarities of perception of relations with other generations are shown in Figure

Notes: Symbols: FISG – Frequency of interaction with the post-war generation; CRISG–Close relations with the Soviet generation; MSG – Misunderstandings with the Soviet generation; TDPSG–Tranquility in dealing with the Post-Soviet generation; CDPSG – Comfort in dealing with the Post-Soviet generation; CRPSG – Close relations with the Post-Soviet generation; MPSG – Misunderstandings with the Post-Soviet generation; r – Pearson's correlation; p – significant (2-tailed)

The results of the study show that the level of contact with representatives of the Soviet generation is related to the perception of relations with representatives of the Soviet and post-Soviet generations. And the frequency of contacts with representatives of the Soviet one reveals direct connections with the perception of this generation and reverse – with the perception of the post-Soviet generation. In other words, people who often communicate with members of the Soviet generation tend to perceive relations with this generation as closer and more understandable to themselves, and relations with the post-Soviet generation as less understandable, less comfortable, less close and less calm.

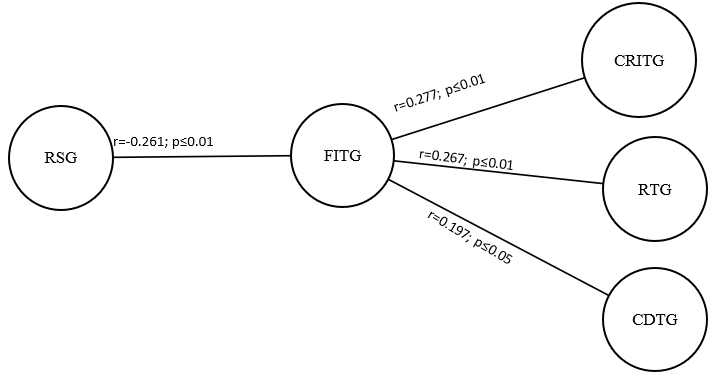

The correlations between the level of contact with the transition generation and the perception of relations with other generations are shown in Figure

Notes: Symbols: FITG – Frequency of interaction with the transitional generation; RSG–Respect for the Soviet generation; RTG – Respect for thetransitional generation; CRITG–Close relations with thetransitional generation; CDTG – Comfort in dealing with the transitional generation; r – Pearson's correlation; p – significant (2-tailed)

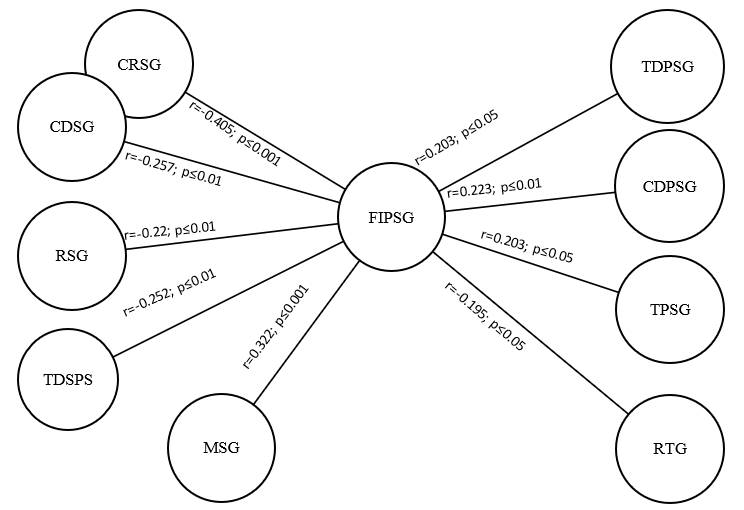

The results of the analysis of correlations between the level of contacts with representatives of the post-Soviet generation and the perception of relations with representatives of different generations are shown in Figure

The number of relationships in the latter case was maximum. This may be due to the fact that the representatives of the post-Soviet generation included the youngest respondents. Assuming that people most often interact with their generation (for example, students with students), it can be concluded that young people are more exposed to the effects of social categorization

Notes: Symbols: FITG – Frequency of interaction with the transitional generation; RSG–Respect for the Soviet generation; RTG – Respect for thetransitional generation; CRITG–Close relations with thetransitional generation; CDTG – Comfort in dealing with the transitional generation; r – Pearson's correlation; p – significant (2-tailed)

Conclusion

The results of the study confirm the theory of social categorization. Frequent contact with a certain generation leads to the perception of a given generation as closer to itself, in other words contributing to identification with it. Frequent contacts with members of a certain generation also contribute to the fact that relations with this generation are assessed more positively and relations with members of other generations are assessed more negatively.

It should be noted that the study has a number of limitations. Factors such as age and generational identification are not taken into account in the study. However, these factors could significantly influence the results of the study, as belonging to a certain generation can determine attitudes towards members of other generations and mediate the perception of relations with them (Sivrikova, Moiseeva et al., 2019; Sivrikova, Postnikova et al., 2019). Therefore, in the future, we plan to consider the influence of age factors and generational identification on the perception of intergenerational relations.

References

- Bae, H., Jo, S. H., Han, S., & Lee, E. (2018). Influence of negative age stereotypes and antiaging needs on older consumers’ consumption-coping behaviours: A qualitative study in South Korea. Int. J. of Consumer Studies, 42(3), 295–305.

- Bocksnick, J. G., & Dyck, M. (2018). Identifying age-related stereotypes: Exercising with older adults. Activit., Adaptat.& Aging, 42(4), 278–291.

- Chu, Q., & Grühn, D. (2018). Moral Judgments and Social Stereotypes: Do the Age and Gender of the Perpetrator and the Victim Matter? Soc. Psychol. and personality sci., 9(4), 426–434.

- Easthope, H., Liu, E., Burnley, I., & Judd, B. (2017). Changing perceptions of family: A study of multigenerational households in Australia. J. of Sociol., 53(1), 182–200.

- Fisher, P. (2020). Generational Cycles in American Politics, 1952–2016. SOCIETY, 57(1), 22–29

- Hamamura, T., Johnson, C. A., & Stankovic, M. (2020). Narcissism over time in Australia and Canada: A cross-temporal meta-analysis. Personal. and Individ. Differences, 155,109707.

- Kashima, Y., Bain, P. G., & Perfors, A. (2019). The psychology of cultural dynamics: What is it, what do we know, and what is yet to be known?Annual Rev. of Psychol., 70(1), 499–529.

- Lauterbach, F., & De Vries, C. E. (2020). Europe belongsto the young? Generational differences in public opinion towards the European Unionduring the Eurozone crisis.J. of Europ. Public Policy, 27(2), 168–187.

- Levy, B. R. (2017). Age-Stereotype Paradox: Opportunity for Social Change. The Gerontologist, 57,118–126

- Lou, V. W. Q., & Dai, A. A. N. (2017). A review of nonfamilial intergenerational programs on changing age stereotypes and well-being in east Asia. J. of Intergenerat. Relationships, 15(2), 143–158.

- Lyons, S. T., & Schweitzer, L. (2017). A qualitative exploration of generational identity: making sense of young and old in the context of today’s workplace, Work, Aging and Retirement, 3(2), 209–224.

- Nimrod, G., & Berdychevsky, L. (2018). Laughing off the Stereotypes: Age and Aging in Seniors’ Online Sex-Related Humor.The Gerontologist, 58(5), 960–969.

- Oró-Piqueras, M., & Marques, S. (2017). Images of old age in YouTube: destabilizing stereotypes. Continuum, 31(2), 257–265.

- Perry, E. L., Golom, F. D., Catenacci, L., Ingraham, M. E., Covais, E. M., & Molina, J. J. (2017). Talkin’ ‘Bout Your Generation: the impact of applicant age and generation on hiring-related perceptions and outcomes. Work, Aging and Retirement, 3(2), 186–199.

- Pishchik, V. I., Gavrilova, A. V., & Sivrikova, N. V. (2016). Styles of Intergenerational Pedagogical Interaction of Teachers and Students of Different Generational Groups. Russ. Psychol. J., 13(3), 245–264.

- Quadir, B., Chen, N. S., & Yang, J. C. (2019). Investigation of the Generational Differences of Two Types of Blog Writers: The Generation Gap Influence. I. J. of Distance Educat. Technol., 17(4), 54–70.

- Schloegel, U., Stegmann, S., Van Dick, R., & Maedche, A. (2018). Age stereotypes in distributed software development: The impact of culture on age-related performance expectations. Inform. and Software Technol., 97, 146–162.

- Schulz, A., Wirth, W., & Müller, P. (2020). We Are the People and You Are Fake News: A Social Identity Approach to Populist Citizens’ False Consensus and Hostile Media Perceptions. Communicat. Res., 47(2), 201–226.

- Sivrikova, N., Moiseeva, E., Sokolova, N., Ertemeva, N., & Zolotova, I. (2019). Perception of intergenerational relationships by people with different types of generational identification. The Europ. Proc. of Soc.& Behavioural Sci.,LXXVI, 2926–2934.

- Sivrikova, N., Postnikova, M., Pyschyk, V., & Miklyaeva, A. (2019). Features of perception of inter-generational relationships. The Europ. Proc. of Soc. & Behavioural Sci., LXXVI, 2935–2943.

- Sivrikova, N. V. (2015). Problems of Research on Generations in Psychology. Cultural-histor. Psychol., 11(2), 100–107.

- Soldatova, G. U., & Rasskazova, E. I. (2016). “Digital gap” and intergenerational relations of parents and children. Psychol. J., 37(6), 83–93/

- Spangenberg, L., Zenger, M., Glaesmer, H., Brähler, E., & Strauss, B. (2018). Assessing age stereotypes in the German population in 1996 and 2011: socio-demographic correlates and shift over time. Europ. J. of Ageing, 15(1), 47–56.

- Steinbach, A., & Hank, K. (2016). Intergenerational Relations in Older Stepfamilies:A Comparison of France, Germany, and Russia. J. of Gerontol.: Soc. Sci., 71(5), 880–888.

- Vauclair, C. M., Rodrigues, R. B., Marques, S., Esteves, C. S., Cunha, F., & Gerardo, F. (2017). Doddering but dear … even in the eyes of young children? Age stereotyping and prejudice in childhood and adolescence. Int. J. of Psychol., 53(S1), 63–70.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

27 February 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-101-0

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

102

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1235

Subjects

National interest, national identity, national security, public organizations, linguocultural identity, linguistic worldview

Cite this article as:

Ptashko, T. G., Perebeinos, A. E., Moiseeva, E. V., Borodina, V. A., & Zolotova, I. A. (2021). Intergenerational Relationship Perception And Intergenerational Contact Frequency. In I. Savchenko (Ed.), National Interest, National Identity and National Security, vol 102. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 788-796). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.02.02.99