Abstract

The article discusses the patriotic accents of advertising texts that were published in the Armenian newspapers of Tiflis. It is shown that advertising texts containing the ethnic codification of a people living in an imperial state system, possessing large trade and economic capital in the colony, and also having clearly formed national-cultural units—language, religion, literature—are most often found in creative advertisements content, while advertising texts for consumer goods and services are generally not nationally labeled. It is noted that most often patriotic texts in advertisements are found during the First World War. In general, the Armenian newspaper advertisement of Tiflis develops in two directions: on the one hand, it serves as a means of transmitting Armenian-language materials in the information and communication space of the Russian Empire and plays an important role in the socio-economic life of the state, in particular, the Caucasian governorate. And on the other hand, advertising has an important intra-ethnic mission: it mobilizes the Armenian people at crucial moments and becomes a means of disseminating and developing the national value system.

Keywords: AraratAniCaucasian Censorship Committeecommodification

Introduction

The emphasis on patriotism has long been used in promotional materials in view of the content in them of the internal potential to promote a product or service. The impact of various advertising mechanisms changes the psychological and behavioral qualities of the audience, and due to the formation of new stereotypes, the value thinking of the person is also affected (Uraleva, 2012).

Modern research in the field of patriotic advertising indicates that the effectiveness of advertising depends on the cultural roots of its recipients, which determines the ratio of national essence and consumer behavior. Addressing the emotional inner world of people, patriotic advertising creates a powerful connection between the country and the people living in it, which is further strengthened during natural or man-made disasters and during an emergency (Yoo et al., 2014). Especially in the war years, such promotional products are created that become an incentive for the population to fight the enemy (Martynov, 2018), thus performing a mobilizing function (Belousov & Manykin, 2014).

Important cultural factors in the impact of advertising are historical memory and consciousness— the main components of national ideology (Savchenko et al., 2017). They are formed thanks to cultural- national codes, becoming a sociocultural mechanism for maintaining the value system (Savrutskaya, Ustinkin, 2019). This leads to the frequent use of national symbols and archetypes in patriotic advertisements, which are an additional recognizable code to arouse consumer interest in the advertised product (Murog, 2017).

Very often, to help their compatriots, people even at the cost of self-sacrifice promote the sale of domestic products (Tsai, 2010); while advertisers, realizing this circumstance, resorting to various expressive advertising means, turn the sale into a kind of ritual, making it possible to appeal to recipients’ patriotic feelings, which in turn have a beneficial effect on the effectiveness of advertising (McGovern, 1998).

Patriotic advertising contains an important incentive for social responsibility. Such advertisements remind consumers of personal or civil liability: choose not foreign, but domestic products. In this case, ethnocentrism based on economic and moral factors becomes important: the consumer realizes that in case of loss of interest in domestic production, the massive flow of foreign goods will lead to an economic crisis, and morality forces consumers to buy domestic production, although inferior in quality to an identical foreign product (Sharma et al., 1995).

The above observations in connection with patriotic advertising only partially reflect the historical development of Armenian advertising, because it occurred in the absence of statehood. Having clearly formed important cultural and national components—language, religion, literature—deprived of statehood and scattered around the world (Figure

Problem Statement

The first Armenian periodicals were printed outside the historical homeland of Armenians. Stemmed in 1794 in India, the vector of development of the Armenian periodical press then moves to Venice, to the cities of the Ottoman and Russian empires, to European, Asian and American cities.

For the most part, the Armenian periodicals did not act as an informational tool for transmitting operational news, but as an intranational communication tool that performed educational and enlightening functions. Since the founding of the Armenian press until 1918, when the birth of the First Republic of Armenia was proclaimed, direct or indirect references focused on uniting Armenians scattered around the

world around one idea—the revival of a lost homeland. In this regard, the Caucasian Censorship Committee noted that the cooperation of Armenians scattered around the world has the common goal of reviving the Armenian people as a political body, and this was facilitated by Armenian newspapers and magazines.

Moreover, patriotic ideas acquired socio-historical significance both in journalistic articles of the periodical press and in advertisements, the informative emphasis of which changed over time under the influence of political, economic and even interpersonal factors.

The capital of Georgia, Tiflis, which in 1801 became the center of the Caucasian governorate of the Russian Empire, was also one of the main cultural centers for the Armenian colony, which makes up the majority of the population. In the 60s of the 19th century, taking advantage of economic reforms, the Armenian trade and production class in a short time created large trading, banking and credit institutions (Yesayan, 2019). In fact, a significant part of Tiflis capital and the levers of power of the city government were mainly concentrated in the hands of the Armenians. The most famous and authoritative Armenian periodicals were also published in Tiflis, which outnumbered the Georgian editions in quantity and circulation but were inferior to the Russian-language press, including that published by the Armenians. However, this quantitative regularity, which dates back to the 1860s and continued until 1918, was maintained thanks to the willful qualities of some individuals, due to the introduction of financial resources, since, according to contemporaries, some Armenians did not know the Armenian language and communicated, wrote and read in Georgian, the elite used Russian, and in some cases the use of Armenian was not encouraged, because it was unfashionable (Artsruni, 1877).

This caused the fragility and published irregularity of most of the Armenian press. This circumstance also influenced the development of printing and advertising, as well as the perception of the press as a means of mass communication and advertising as a form of mass communication: publishing a press, subscribing to it, sponsoring a print of a publication in itself was considered an indicator of patriotism and contributing to preservation and development of national education circumstance. In view of the conditionality of these factors in the Tiflis-Armenian periodical press, there are noticeable components of personal advertising (for example, praise, exaltation of various persons), the external side of which was wrapped in direct or indirect messages of a patriotic nature. In some cases, the unselfish contribution to the printing business was reimbursed to the contributor by the opportunity to gain good fame or influence public opinion.

For the Armenian periodicals, advertising was an additional, but not the main means of income. Armenian publishers periodically raised the issue that Armenian entrepreneurs prefer to print their advertising materials in foreign-language periodicals. Private individuals also had similar preferences, who ordered their prints, including obituaries, to print foreign-language periodicals. The paradox is also observed in the activities of Armenian charitable companies operating in Tiflis, which asked the Armenian press to print their ads for free or at a great discount, despite the fact that the purpose of these companies was to provide material and intellectual assistance to Armenians and to disseminate education. Many press ads were printed for free, and thus the social role of advertising increased, and such ads more often performed a social function than pursued commercial goals. Advertising in the Armenian press was in itself considered a manifestation of patriotism and national ambition (Danielyan, 2018). However, it is noticeable that in the formation of the national system of values, advertising materials had a clearly formed stratification.

Armenian advertising, as a means of spreading patriotism, has never been investigated, and the relevance of the topic is due to this very factor. At the same time, a study of this topic makes it possible to see how national advertising develops outside the historical homeland, in the imperial system and, in particular, what emphasis on patriotic ideas have advertising materials.

Research Questions

1,500 promotional materials from the advertising sections of eight newspapers published in 1846- 1918 were studied (in the marked period, no clear genre distinctions were made between advertising and the announcement).

The studied newspapers were selected taking into account the following two factors: the duration of printing (minimum 5 years: “Megu Hayastani” (“Bee of Armenia”, 1858–1882), “Mshak” (“Worker”, 1872–1918), “Nor-Dar” (“New Age”, 1883–1907),“Ardzagank” (“Echo”, 1882–1898),“Orizon” (“Horizon”, 1909–1918),“Ovit” (“Valley ”, 1910–1917); and uniqueness (other press, including magazines, were not published during this period: “Kovkas” (“Caucasus”, 1846–1847), “Ararat” (1850–1851).

The study focused on advertising material for consumer goods, services and creative production, 500 advertising materials for each group.

Purpose of the Study

The aim of our article is to identify the patriotic accents of advertised materials of the Tiflis- Armenian periodical press. The task is to identify the informative transformations and their semantic forms, to find out the factors affecting the development of patriotic advertising.

Research Methods

Using content analysis, we extracted information from advertising texts that contains various codes of a national or state value system, including archetypes, symbols or their meanings, as well as the terms “the Armenians”, “Armenian”, “national”, “homeland”. The documents of the Russian State Historical Archive and the National Archive of Georgia were also studied.

Findings

The Tiflis-Armenian periodicals initially led a literary-centric policy. Until the 1860s, when trade and production relations began to develop at a new pace in Tiflis, the press mainly printed advertisements for creative production (in particular, bibliographic). Since the 1880s, the picture has changed: the quantitative ratio of advertising of creative products, consumer goods and provided services is changing in favor of the latter.

Now consider retail advertising for various groups: advertising of consumer goods, advertising of services, advertising of creative production.

Consumer Product Advertising

In 1846-1918, in the Tiflis-Armenian press, the “European”, “American” and similar characteristics occupied a dominant position in the advertising of household goods, food, and drinks. Cigarette advertisements often emphasized the “Turkish” origin of tobacco. Foreign goods were presented as high quality and stylish. In the advertising materials of local goods, either the foreign origin of the raw materials or their qualitative similarity with a foreign product was emphasized (for example, NI Bozardzhyants tobacco factory in Tiflis: “I offer to the public attention the freshly obtained cigarettes of the latest system, made on American machines from the best French paper. We just got fresh Turkish and local tobacco of better quality” (Cigarettes factory Bozardzhyants, 1891).

Until the beginning of the 20th century, locally produced consumer goods generally did not have special names, and the name of the owner of the plant was most often noted. With the development of production and trade and economic relations, pragmatonyms become a necessity for a product to highlight and promote it on the market. Of the 500 products studied, the following products had the Armenian national code:

"Select Lori honey. Sold at the Melik-Bakhtamyants dairy store.” (Lori honey, 1898). In this advertisement, the guarantee of high-quality honey is the place of its origin—the territory of the historical Lori kingdom (982–1113). However, the concept of "Lori" is just an indication of the geographical territory and in this case does not contain essential elements of the national code.

"Pure Caucasian cognac "Ararat". It has no competitors in quality...” (Cognac Ararat, 1911). Although the name of the product is based on the name of the mountain, which is considered an Armenian archetypal symbol, the advertising material does not contain a pronounced Armenian marking, because on the market it acts as a Caucasian cognac. By the way, for comparison, we note that mineral waters produced in the Caucasus (Natural waters Narzan and Essentuki no. 20, 1911), drinks (Lemonade Lagidze, 1911) and wines (Wines Kakheti, Derbenti, Matrasi, 1892) were advertised in the same way. Their Caucasian origin was emphasized.

3. "Ararat” cigarettes. It was produced at the tobacco factory of the Seilanyan Brothers company, but the advertisement for this product was printed only as the name of the product next to the names of other cigarettes (Ararat Cigarettes, 1910). Unlike other advertised cigarettes, the advertisement of Ararat cigarette was not printed separately in Armenian newspapers.

5. "Ani" cigarettes. In the tobacco advertisement of the Mir factory, a box is also presented, which shows a general view of the citadel of the historical capital of Armenia, Ani (961–1045) (Cigarettes Ani, 1913). It must be noted that the assortment of cigarettes produced in Armenian factories was mainly represented by names of non-Armenian origin that do not contain national meaning (1914), Zolotye cigarettes (Cigarette of the Bozardzhyants firm, 1911), Druzhba cigarettes, Comrade cigarettes (1910) of the Bozardzhyants brothers (Cigarettes of the company Bozardzhyants: Friendship, Comrade, 1910), Cigarettes of the company Brothers Seilanov: Sunrise, Zephyr, Mars (1910).

In 1914, when the First World War began, patriotic codes were clearly indicated in the advertisements of some consumer goods. For example, the “Military” cigarettes (“The quality of the “Voyennyie” cigarettes, like our brave warriors, is beyond praise” (Cigarette company Brothers Saylanov, 1915). The store owners adapted the assortment of goods to the requirements of war situation and indicated in bold letters the addressees of the goods being sold (for example: woolen socks, gloves, hats (helmets) were made for the MILITARY, WOUNDED AND REFUGEES .... (Sale of goods for the military, 1915). In this case, advertising served primarily the function of rallying, commodifying the military theme, and was presented to the reader in the form of social advertising.

Advertising of services

In the noted period, the names of the trading houses were dominated by the names of the founders or owners (The shop of Grigor Nasibyan, 1878), sometimes the corresponding toponyms of the goods produced (London store, 1883). The owners of most of the stores advertised in the Armenian press were Armenians, but there was no emphasis on national orientation in the advertising materials.

Teaching service advertisements had a certain national emphasis. With their help, teachers of Armenian schools and colleges were invited to work. To teach the new generation the national language, history and other subjects, changes in educational programs, as well as administrative reports and notifications of educational institutions (for example, announcements of the Nersisyansky school).

(Nersisyan College, 1884), were presented. Initially, such ads were printed for free, for the benefit of national education, and in fact performed a narrow national social function.

Expressed national features contained ads of charitable institutions. Announcements on holding various charity events, lottery drawings, walks were periodically printed in newspaper advertising sections, and during the First World War similar announcements were printed in almost all newspaper issues. In advertisements for events of various formats, their charitable purpose was noted. They had both national (for example, for refugees from the Ottoman Empire and, in particular, from the territory of Western Armenia (Concert of the choir of the Nersisyansky school, 1915), and national importance (for example, after 1914 to help military personnel (Assistance to the military of the Caucasus Front, 1916).

Creative production advertisements

Most of the advertisements for creative production until the 80s of the 19th century were printed for free, or at big discounts, since at the initial stage of advertising in the Armenian periodical press the idea of national education and business benefits came in parallel.

Even price lists and catalogs of Armenian bookstores were printed for free. However, with the development of printing and the intensification of competition, the printing of these advertisements was also subject to market laws. Changes in the market of printing, executive and applied arts directly affect the content of advertising sections. Before World War I, advertising was used more often in order to appeal to historical memory and consciousness (Raffi & Beck, 1897), but during the war years advertisements for the sale or exhibition of works of some kind of art devoted to the patriotic themes of modern times began to prevail. Symbols of national significance were modified and advertised. Biographies of the life of famous national figures and heroes of liberationstruggle became the core of creative production, the development of sales of which was facilitated by newspaper advertising (for example, “Razmi Herger” (War Songs, 1915), “Arshaluysi zayner” (The Sound of Dawn, 1915), accompanied by photographs of the oath of the heroes of the Armenian national liberation movement: Andranik, Amazasp, Keri, Dro, Vardana, volunteers and many old and new military and Hajduk songs and poems).

The applied significance and material value of the advertised goods give way to national-patriotic ideas and values of the spiritual essence of the people. It should be noted that, unlike the previous types of advertising, in the advertisements of creative production quantitatively prevail materials aimed at national and patriotic feelings. And it is no coincidence that until the beginning of the 20th century, advertisements for creative products often ran into censorship obstacles.

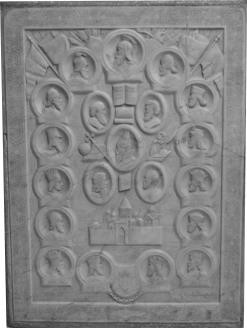

For example, a poster depicting a 5th-century Armenian commander who liberated Armenia from a foreign yoke, Vardan Mamikonyan, and a participant in the church liberation struggle, priest Ghevond, advertisements for the engraving “Park Hayastani” (“Glory to Armenia”: the image of Armenian kings) and photographs “Vogi Hayastani” (“Soul of Armenia”) the Caucasian Censorship Committee considered inadmissible (Engraving Glory to Armenia and photograph Soul of Armenia, 1895), since the allegorical content of the paintings had a narrow national orientation, And advertising was perceived as an ideologically directed tool.

Since the censorship bodies of the Russian capitals had a more loyal approach to materials with a national focus than the censorship committee of the Caucasus (in Tiflis there was strong competition between publishing houses that print in national languages), Armenian publishers very often turned to censorship bodies of St. Petersburg or Moscow.

Conclusion

Thus, it can be stated that modern theories on the correlation of patriotism and consumer behavior do not primarily reflect the consumer preferences of peoples without statehood, because for them the consumption of goods and services does not intersect with a sense of national essence. National codes in the names of goods are also not widely used, because according to market laws, the marketing of consumer goods and the trading philosophy of providing services do not fit into a narrow national framework. Contrary to this, creative production is very important in the formation of patriotic ideas and national essence.

Using the example of the Tiflis-Armenian periodicals of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it can be stated that consumer goods generally have no national, patriotic messages, although there are no special prohibitions on this.

The presence of a national element in advertising services is predominantly neutral. In this group, pedagogical advertisements or notices of charity events have a certain patriotic marking. The main core of the patriotic theme is the advertising of goods of creative production, and, due to the pronounced national coloring, advertising of the cultural industry is faced with censorship prohibitions.

In general, the advertisement of the Tiflis-Armenian periodical press, as a conductor of patriotic ideas, carried out important socio-cultural functions, the significance of which was especially pronounced during the First World War. In one case, it was supranational, fulfilling the function of rallying in the name of the national good in the information and communication system of the Russian Empire, in the other case, it was of national importance, becoming an expressive means of the formed national value system, as well as a means of presenting analogues of trends in the development of the value system of the Armenian people.

References

- Ararat Cigarettes. (1910). Advertising. Horizon, 64.

- Artsruni, G. Y. (1877). The unnatural state of our journalism. Mshak., 8.

- Assistance to the military of the Caucasus Front (1916). Social advertisement. Horizon, 73.

- Belousov, L. S., & Manykin, A. S. (2014). The First World War and the fate of European civilization. Publ. House of Moscow Univer.

- Cigarette company Brothers Saylanov (1915). “Voyennyie”. Advertising. Horizon, 30.

- Cigarette of the Bozardzhyants firm (1911). Advertising. Horizon, 137.

- Cigarettes Ani (1913). Advertising. Horizon, 4.

- Cigarettes factory Bozardzhyants (1891). Advertising. Nor-Dar, 153.

- Cigarettes of Enfiachyan's company: Golubka, Intelligentyi, Extra. (1914). Advertising. Mshak, 281.

- Cigarettes of the company Bozardzhyants: Friendship, Comrade (1910). Advertising. Mshak, 63.

- Cigarettes of the company Brothers Seilanov: Sunrise, Zephyr, Mars (1910). Advertising. Horizon, 64.

- Cognac Ararat (1911). Advertising. Mshak, 84.

- Concert of the choir of the Nersisyansky school (1915). Advertising. Horizon, 101.

- Danielyan, T. R. (2018). Criticism of Advertising and Advertising Activity in the Newspaper “Nor-Dar” (1883–1907). The Fifth Int. Sci. Conf. “Language and Literature in the Context of Intercultural Communication”. Yerevan, Misma (pp. 207–216) (in Armenian)

- Engraving Glory to Armenia and photograph Soul of Armenia (1895). Advertising. Mshak, 35.

- Lemonade Lagidze (1911). Advertising. Horizon, 137.

- London store, (1883). Advertising. Mshak, 83.

- Lori honey (1898). Advertising. Mshak, 240.

- Martynov, E. V. (2018). Social advertising in solving the tasks of patriotic education and propaganda: a comparative political analysis. https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/sotsialnaya-reklama-v-reshenii- zadach-patrioticheskogo-vospitaniya-i-propagandy-sravnitelno-politologicheskiy-analiz/viewer.

- McGovern, C. (1998). Consumption and citizenship in the United States, 1900–1940. In S. Strasser et al. (eds.), Getting and spending: European and American consumer societies in the twentieth century. Cambridge Univer. Press; NY, pp. 3758.

- Murog, I. A. (2017). On the study of the persuasive power of the archetype in the advertising text (for example, American military advertising). https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/k-voprosu- issledovaniya-persuazivnoy-sily-arhetipa-v-reklamnom-tekste-na-primere-amerikanskoy-voennoy- reklamy.

- Natural waters Narzan and Essentuki no. 20 (1911). Advertising. Mshak, 84.

- Nersisyan College (1884). Advertising. Ardzagank, 29.

- Petrosyan, D. V. (2007). Literary debate in the Armenian press of the early 20th century. Publ. House of Yerevan State Univer., p. 22 (in Armenian).

- Raffi, S., & Beck, D. (1897). Historical novels by Raffi: “Samvel”, & “David Beck”. Advertising. Mshak, 100. Sale of goods for the military (1915). Advertising. Horizon, 26.

- Savchenko, I. A., Snegireva, L. A., & Ustinkin, S. V. (2017). Historical memory in emotional and exploratory perception, Vlast’, 25(10), 112–122.

- Savrutskaya, E. P., & Ustinkin, S. V. (2019). Historical memory as a factor of national security. Vlast’, 27(6), 225–231.

- Sharma, S., Shimp, T. A., & Shin, J. (1995). Consumer ethnocentrism: A test of antecedents and moderators. J. of the Acad. of Market. Sci., 23(1), 26–37.

- The shop of Grigor Nasibyan (1878). Advertising. Mshak, 215. The Sound of Dawn (1915). Advertising. Horizon, 131.

- Tsai, W. S. (2010). Patriotic advertising and the creation of the citizen-consumer. J. of Media and Communicati. Studies, 2(3), 076–084.

- Uraleva, E. E. (2012). Advertising as a social institution. Izv. Penzenskogo Gos. Pedagog. Univer., 28, 588–593. https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/reklama-kak-sotsialnyy-institut/viewer.

- War songs (1915). Advertising. Horizon, 101.

- Wines Kakheti, Derbenti, Matrasi (1892). Advertising. Nor-Dar, 99.

- Yesayan, V. B. (2019). The activity of Armenian bourgeoisie in the state of Tiflis in 1846–1917. [Doct. Dissertation]. Yerevan, p. 4 (in Armenian).

- Yoo, J. J, Swann, W. B., & Kim, K. K. (2014). The Influence of Identity Fusion on Patriotic Consumption: A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Korea and the U.S. The Korean J. of Advertis., 25(5), 81–106.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

27 February 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-101-0

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

102

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1235

Subjects

National interest, national identity, national security, public organizations, linguocultural identity, linguistic worldview

Cite this article as:

Danielyan, T. R., Santoyan, A. M., & Savchenko, I. A. (2021). Advertising As A Means Of Disseminating Patriotic Ideas In Tiflis-Armenian Newspapers. In I. Savchenko (Ed.), National Interest, National Identity and National Security, vol 102. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 178-186). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.02.02.23