Abstract

In 2018, Russia witnessed one of the most dramatic events influencing both its economy and political landscape that is the government's decision to raise the retirement age. This decision affected the welfare of almost all Russian citizens. Many of them, especially those who have almost reached their retirement age, expressed an extremely negative reaction in response to this innovation. The purpose of this work is to prove that not only the increase in the retirement age, but also a number of recent transformations in the pension system established at the beginning of the twenty-first century, have obtained clearly "anti-market" characteristics. For this, the study compares the content of the two programs: the first is the program named "Monetization of benefits", implemented at the initial stage of reforming the pension system; the second one is "Retirement-age increase" program. Using the demarcation criterion, the authors has come to conclusion that the recent changes in the pension provision lead to the creation of a new system, where the centre is the state, taking all the responsibilities in order to provide Russians of the retirement age with incomes. Market mechanisms of pension capital formation, i.e. mechanisms of individual choice, either stopped working or lost their effectiveness.

Keywords: Monetizationbenefitspension reformtrust

Introduction

The modern Russian economic landscape was under the influence of two multi-directional forces. The first trend was the radical market reforms initiated in 1992 and successfully continued for about a decade. The second force, qualified as a counterforce to market reforms, was the tendency to strengthen the state's participation in economic processes. This tendency is evident from the following: firstly, the public property sector is growing fast enough; also, all new sectors of the economy are away from the market forces and involved in the sphere of bureaucratic management. The trend appeared when the Russian economy got rid of the chronic budget deficit. However, the balance of the budget was not the only factor making the market reforms slow down. Another reason was strategic errors that come from the gradualist nature of the reforms instead of the "shock therapy «scenario recommended in such cases. The peculiarities of cultural capital, which was typical of the majority of Russians, were also very significant (Bourdieu, 1973; Grondona, 2000). After the liquidity crisis of 2008–2009, the Russian economy began to look more and more like a centralized economy model. This movement towards bureaucratization did not exclude such a vast sector of the economy as pension provision for Russians;

Problem Statement

Consequently, the authors of the research faced a problem that is to assess the implemented pension reform in terms of its attitude to market reforms. According to the authors, the attribution of alternating actions of the economic authorities to the field of market or "anti-market" reforms depends on a demarcation criterion. It is based on the assumption that all the actions leading to a wider range of choices for an individual and to the reduction of his/her dependence on the state are market reforms. If this dependence remains or even increases, and the number of alternatives available to an individual reduces, the reforms are "anti-market" or bureaucratic.

Research Questions

There are many reasons that push the political authorities to choose a particular pension system. However, purely economic reasons are often less important than political, historical, social or cultural ones. In each country, the set of factors that determined the choice of the pension model and its evolution is unique. Russia is no exception in this respect.

Purpose of the Study

The pension system currently existing in Russia bears the imprint of Russian history. For about ten years (counting from the beginning of market reforms in Russia), this system was a tracing paper with the pension system of the USSR. Having solved tactical problems, the political authorities of Russia began to transform the pension system. According to the original plans, it was supposed to shift in the direction of less and less participation of the State in the financing of pensions. However, very soon there were events that turned the vector of pension reforms in the opposite direction. At the same time, the state overloaded itself with obligations. At first, the threat of default looked far-fetched. However, after the financial crisis of 2008, the budget vs. pension dilemma became fully apparent. Currently, the Russian Government has taken some steps to adapt the pension system to the current state of the budget. These actions allow predicting future events.

Research Methods

The article presents a comparative analysis of the two alternatives for pension reforms, separated by the period of 15 years. The first is known as "Monetization of benefits", the second is named "Pension reform". Comparing these two options, the study establishes the correlations of their content with the scenario called "market reforms".

Pension provision transformation has a universal character. Since the nineteenth century, when the prototypes of modern pension systems emerged, the developed countries have been forced to continuously change the pension schemes in order to meet the challenges that inevitably arise as a result of the unpredictability of future events. The examples of such unexpected changes are a sharp increase in life expectancy or a significant increase in fertility in some countries after the Second World War (Greenspan, 2010). Pension problems affect all residents of the state (although the degree of these impacts differs). Therefore, the strategy of transformation should be designed quite skilfully. The main purpose of the study is to compare the two Russian reforms of pension provision carried out with an interval of 15 years, examining the degree of their effectiveness. In addition, the researchers focus on the side effects that ensure the success of the first reform the complete failure of the second one.

The study of household consumption, as well as its propensity to save and invest, has a relatively short history. The first scientist who put these issues into the focus of economic dynamics was Keynes (2007). He also developed a hypothesis of a falling marginal propensity to consume as a function of household income. Later, this hypothesis was investigated by Simon Kuznets, who verified it with a longer period of evidence compared with Keynes data. Moreover, Kuznets stated that the function of household propensity to consume is constant related to the amount of income it receives (Kuznets, 1946). These two hypotheses, seemingly opposed, were reconciled by Milton Friedman in his theory of the consumption function (Friedman, 1957). After this, many well-known economists studied the behaviour of households that decide on the allocation of their costs in the inter-temporal space, such as Franco Modigliani (Ando & Modigliani, 1963) and Martin Feldstein (Feldstein, 1977). They, in particular, developed models of permanent income and life cycle savings, which helped us to analyse the preferences of Russian households. The study applied the method of indifference curves to study the process of optimization of individual household choice in the inter-temporal space. After integration with the final model of budget constraints, this method has become a corner stone of the analysis of choice situations at the micro level (Buchanan & Tullock, 1975) and at the level of the national economy and international trade (Leontief, 1933).

Findings

The reform known as "monetization of benefits", consistently, attracted attention. Apparently, this was the last event to date, implemented at the Federal level, that was in the initial "relic" package of market reforms conceived in the early 90-s of the twentieth century.

The content of the "monetization of benefits" was that all households entitled to numerous in-kind benefits could waive them in exchange for monetary compensation. The reform occurred under the conditions of a negative emotional landscape. However, when making a real choice, the vast majority of the population (in the first year after the reform, there were 9 out of 10 citizens who had the right to benefits) chose a small but guaranteed amount of money, abandoning the natural benefits, the usefulness of which seemed very insignificant to them.

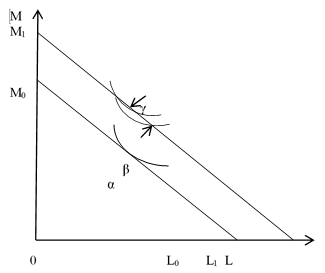

The history of monetization of benefits is cautionary. It is an accurate formula for the success of the reforms. The first component of this success is confidence in the final result. In the case of monetization of benefits, the result, that is the choice of the monetary component, accurately corresponded to the predictions of economic science. Let us consider Figure

The abscissa axis measures the volume of goods and services that can be bought by an individual or paid for by the government (in the second case, these values become benefits). The ordinate axis measures the amount of other goods that a household can buy only with money. At the initial moment, a household buys all the goods on its own. The budget line L0M0 shows household opportunities (at a set income and prices). A household optimizes the selection by being at point

It is at position

Individual household preferences are unknown to the government. By providing in-kind benefits, the government simply applies a single template to different households. Consequently, for many of them, the goods and services included in the "preferential package" do not have the value that officials assign to these benefits. After receiving the money, households will abandon the acquisition of benefits from the preferential list and begin to acquire benefits corresponding to their individual preferences. There is an extensive empirical base verifying the proposed model.

This analysis is to show that, in fact, the risk that the reformers took was very small. Despite the fact that the policy of reforms looked dangerous, its result was quite predictable. The only obstacle to the beginning of the reform was its negative perception formed by the correspondent information attack. Accordingly, the second component of successful reforms (after a precise scientific verification of the first steps results) is the existence of a strong political will, that is, the ability to put in place a mechanism of reforms, even if these reforms are extremely unpopular among the population. The political will is conditioned by the popularity of the political leader or the weight of his track record, his reputation (Witte, 1994). In many respects, the success of monetization of benefits was the result of the fact that the team of reformers was already trained (Tyrol, 1996). After all, they have already managed to go through such large-scale events as price liberalization, privatization and electric power industry reform.

Monetization of benefits conceived to become another link in a long chain of subsequent reforms stopped. It was the last episode in this scenario. The main reason for this, in the view of this study, was the lack of the second component necessary for success that is political will. The political will is not to start painful reforms in the situation of a deadlock. It is to begin these reforms when voters do not see the need for them.

15 years have passed after the triumph of the "monetization of benefits" reform, and the government made a new unpopular decision that was the increase in the retirement age for the majority of working Russians. The event is "Pension reform" by a coincidence perceived as a continuation of long-forgotten market ("liberal") reforms.

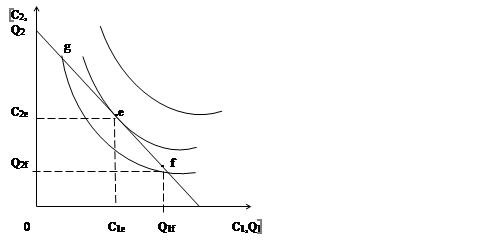

Pension reform was to start at the very beginning of the XXI century, and "monetization of benefits" was one of the initial stages of this reform. The main idea was to distribute the responsibility for old-age pension provision between the entrepreneur and the employee, excluding the state involvement if possible. The workers had the possibility of inter-temporal choice: by donating a part of current income, they could increase future pension (Arrow, 1962; Sachs & Larren, 1999). This household decision is shown in Figure

The main part of household output (income) is concentrated in the current period and is equal to Q1f, while in the future period (in old age) the amount of income is much less (Q2f). If the financial market is not developed enough, households are forced to adjust their current consumption to the amount of current income. This means that a household is initially at point f. The household considers that it is advantageous to reduce its current consumption to C1e, and to transfer the rest of the income in the amount of [Q1f – C1e] to a future period. This allows it to increase its consumption in the future by [C21e – Q2f] and move to the point e on the higher indifference curve. It is a signal that financial market will allow the household to increase its wealth obtained not in the current period, but throughout life.

This plan of pension reform was to create the specific institutions and financial instruments enabling households to make such choices. The differentiated choice of households in the current period ensured their unequal well-being in old age. This is the distinguishing feature of any "market" reforms, as they are to provide each individual with a wider range of alternatives, while reducing the share of state participation.

The original design of the pension reform vanished in the middle of the first decade of the XXI century. Soaring federal budget revenues due to favourable conditions in the global hydrocarbon market make the political leaders of the country in front of a dilemma: to continue reforms or "to make a break". The Russian authorities failed to cope with the temptation of populism. The government refused to balance the Pension Fund and increased the slope of the trajectory of pension growth at the expense of the state budget. This was too ambitious and even risky program, which became obvious after the events of autumn and winter in 2014. The price of oil on the world market in the second half of 2014 fell by half, and the real burden on the budget, created by obligations to the Pension Fund, became unbearable. The unpopular adjustment of the pension scheme was a matter of time. This time came in the summer of 2018 when the government announced the postponement of the retirement of Russians for 5 years.

The two questions remain. The first question is whether this step can be called "reform". Secondly, can this action be classified as a continuation of market reforms? It is assumed that when the reform is completed, it is possible to describe its result with the phrase: "the problem is solved." It is obvious that the disposition formed after the increase of the retirement age does not correspond to this condition. These actions are an instantaneous, or as economists define it, "situational" adjustment. It helps to solve the problems that have arisen "here and now". But what will happen when the additional income generated by this simple manipulation is exhausted? This will happen quite soon, as the government does not create "reserve funds" that would help to smooth the fluctuations in the economic situation in the future period, but it immediately directs funding to increase the pensions size of the current pensioners.

Based on today's circumstances, the prediction is that the retirement age will increase in the future. The danger is that after some time, a step-by-step increase in age of working people will completely absorb the so-called "survival period". This hypothesis may seem an inappropriate joke, but the current pension policy does not offer any alternatives.

Thus, Russians expressed obvious disapproval of the decision to raise the retirement age coming into effect from the beginning of 2019. In a social science perspective, the authorities denounced the social contract implicitly concluded between them and the population of Russia at the beginning of the XXI century. The content of this implicit contract was that the population agreed to abandon market reforms in exchange for constant growth of welfare. It should be recalled, however, that the increase of the retirement age was preceded by other actions of the government that were contrary to the above-mentioned contract. At the beginning of 2016, the government resolutely renounced earlier commitments to annual indexation of pensions in strict accordance with the rate of inflation. Although inflation in 2015 was 13 %, pensions were indexed by only 4 %. It is easy to calculate that such a step led to a decrease in the real pension by 9 %. As soon as the state of the budget, ruined by the crisis and the subsequent recession, stabilized, the government compensated about half of these losses. Then, the rule of full indexation of pensions was restored, but not for everyone. Working pensioners did not fall into this category, and since 2016 the growth rate of their nominal pensions has been chronically lagging behind the rate of inflation. The government can come up with any, even the most sophisticated arguments to justify its actions, but this does not change the fact that it unilaterally renounces its obligations.

Is it possible, reviewing the government pension policy, to categorize this sequence of actions as a "reform"? It seems to us that these actions are more in line with the scenario known as "patching holes". They do not affect lessen this problem in the future, and in any case, they do not eliminate it. Now it is time to answer the second question: should the recent efforts of the government to solve the pension problem be considered continuing the course of market reforms? The demarcation criterion will help us here. It is clear that the actions of the government discussed above do not meet this criterion. The list of "crimes against the market system" is so long that we will mention only the most dramatic ones. First, there are still no reliable financial institutions and instruments that allow individuals to regulate their well-being in the future (Bogatyreva, Kolmakov, & Balashova, 2019). So far, they can only operate with short-term general-purpose financial assets. Secondly, the link between the contribution to the Pension Fund financed by the employer and the size of the individual's future pension has disappeared. Third, a fairly simple formula for the formation of an individual's pension, which uses the national currency (rouble) as a unit of measurement, is replaced by the use of pension points. The monetary value of this "point" does not depend on the will and activities of individuals, it is determined by the government on the basis of "budget parameters". Fourth, the government will not stop changing the "rules of the game" on the pension field. Will a rational individual invest for 25–30 years in advance if the rules of the game can change in 2–3 years? All these facts show that pension provision in modern Russia is rapidly turning into a system where the state assumes all obligations to ensure the income of the population in old age, removing from this function both private sector and pensioners (Bogatyreva et al., 2019). None of the political leaders is hiding the general direction, apparently considering the state pension system as the best solution to the problem. It is not a coincidence that the preamble to the decision of raising the retirement age stated that in exchange for a longer working period, the government guarantees future pensioners a higher amount of cash payments. There is no question of any alternative forms of pension increase. Thus, the economic policy makers consciously prevent the Russians from using the market as a tool to ensure the flow of pension income. Accordingly, the decision to increase pensions should be considered anti-market. It is also worth noting the striking difference between the mode of representation the decision to raise the retirement age and the scenario of "monetization of benefits". Before making the decision about monetization of benefits, there was a continuous and open to the general public discussion, in which participants freely exchanged alternative views. Although the attitude of the majority of Russians to the upcoming monetization was negative, many citizens consciously supported the initiative of the government at the preliminary stage. As for the decision to raise the retirement age, it was adopted without any prior discussion. We can say that the participants of the experiment were obliged to accept it. Only later, the ruling elite began to list the many benefits that they believed would come from a postponed retirement. Let us leave aside the content of the arguments. It is quite possible that they are true. Regardless of the weight of these arguments, we can say that the "rearrangement of moves" made by the government (the decision is before the discussion, but not vice versa), awakened very gloomy memories in the Russian public.

Conclusion

The trust of the population that is such a powerful tool of preserving power is unknown to the authorities of a totalitarian country, because it is not necessary. It seems that in any democratic country, including modern Russia, the trust of the population will be taken into account by the ruling elite. It is enough to mention that the policy of decision-making "in a narrow circle", without taking into account the opinion of the general public, without public discussion of alternative solutions to the problem, does not contribute to the formation of trust. It is the very trust, without which it is impossible to carry out radical reforms, and this is evident not only from distant "world «experience, but also from suffered by a whole generation of Russians personal one. The question remains how the transformation of the Russian pension system, which began in the direction of the widespread use of the market mechanism and the independent participation of people in the formation of their pensions, then, turned in the opposite direction. We agree, however, that this is a completely different problem, and it is already under the investigation.

References

- Ando, A., & Modigliani, F. (1963). The" life cycle" hypothesis of saving: Aggregate implications and tests. The American economic review, 53(1), 55-84.

- Arrow, K. (1962). Economic Welfare and the Allocation of Research for Invention. The Rate and Direction of Inventive Activity: Economic and Social Factors, 609–626.

- Bogatyreva, M. V., Kolmakov, A. E., & Balashova, M. V. (2019). Decent Pension VS Balanced Budget: The Russian Solution to the Dilemma. Proc. of the Int. Conf. on “Humanities and Social Sciences: Novations, Problems, Prospects” (HSSNPP 2019). Retrieved from:

- Bourdieu, P. (1973). Cultural reproduction and social reproduction in knowledge, education and cultural change. London: Tavistock.

- Buchanan, J. M., & Tullock, G. (1975). The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy. Michigan: The University of Michigan.

- Feldstein, M. (1977). Social Security and Private Saving: International Evidence in an Extending Life–Cycle Model. London: Macmillan.

- Friedman, M. (1957). A Theory of the Consumption Function. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Greenspan, A. (2010). The Age of Turbulence. Problems and Prospects of the Global Financial System. Moscow: United Press Ltd.

- Grondona, M. (2000). A Cultural Typology of Economic Development. Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress, 44–55.

- Keynes, J. M. (2007). The general theory of employment, interest and money. Moscow: Exmo.

- Kuznets, S. (1946). National Income, Summary of Findings. New York: National Bureau of Econmic Resources.

- Leontief, W. W. (1933). The use of indifference curves in the analysis of foreign trade. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 47(3), 493-503.

- O’Sullivan, A. (2002). Economy of the city. Moscow: INFRA-M.

- Sachs, J. D., & Larren, F. B. (1999). Macroeconomics. Global approach. Moscow: A business.

- Tyrol, Zh. (1996). Markets and Market Regulation: Theory of Industrial Organization. St. Petersburg: Econ. Schoo.

- Witte, S. Yu. (1994) Memories. Moscow: Skiff alex.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

07 December 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-095-2

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

96

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-833

Subjects

Management, human resources, resource efficiency, investment, infrastructure, research and development

Cite this article as:

Bogatyreva, M. V., Matveev, N. V., & Bogatyrev, K. D. (2020). Monetization Of Benefits And "Pension Reform". In A. S. Nechaev, V. I. Bunkovsky, G. M. Beregova, P. A. Lontsikh, & A. S. Bovkun (Eds.), Trends and Innovations in Economic Studies, Science on Baikal Session, vol 96. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 83-91). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.12.12