Abstract

The government of Malaysia has recently been urged to increase the mandatory retirement age of employees from 60 to 65 years old. It prompted many reactions from the netizens, labour unions, politicians as well as the publics. Some say the higher retirement age will thwart the country’s development as the younger generation will have less job opportunities. However, some say by raising the retirement age, the economic growth would be better as life expectancy of people has increased and the country is lacking of workforces. This paper descriptively examines the impact of increasing the retirement age from perspective of demographic and health, graduates’ labour market and the government’s fiscal policy. The analysis canvasses several financial and non-financial indicators provided by Bank Negara Malaysia, Department of Statistics, Ministry of Education and Ministry of Finance. The analysis generally concluded that at current economic growth, recent trend of graduates’ labour market and current demography and health pattern, Malaysia is not yet ready to increase the retirement age to 65.

Keywords: Economic analysisgraduates labour marketMalaysiaretirement age

Introduction

Retirement age is the age at which a person is expected or required to cease work and is usually the age at which they may be entitled to receive superannuation or other government benefits, like a state pension etc. Statutory retirement ages are difference in every country. Typically, the policy maker or the government will consider the demography, fiscal cost of ageing, health, life expectancy, nature of profession and supply of labour force in deciding the retirement age. Today, the retirement age varies from a minimum of 45 years in Turkey to 70 years in Australia. According to an analysis carried out by The Star where the information on the retirement age, life expectancy and the proportion of the elderly among the population in 153 countries were collected, a total of 62 countries set 60 as the retirement age, while the second most common age is 65, which is in place in 35 countries. According to a source from United Nations (UN) data and news reports, 60 is the single most common age for retirement among the countries surveyed.

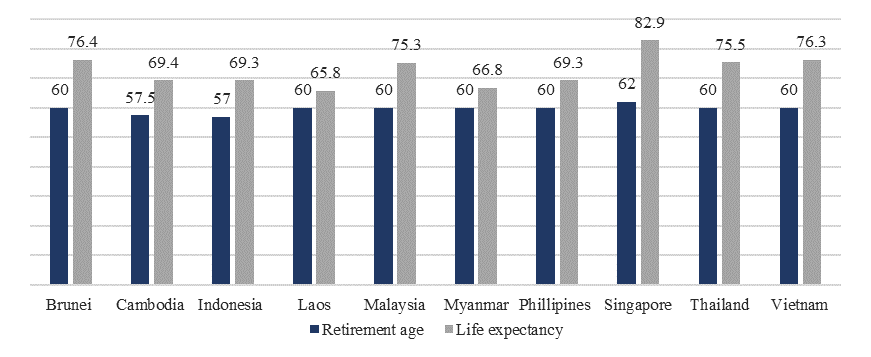

While majority of Malaysian disagree on the extension of the retirement age, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) however reported that as life expectancy continues to rise, the governments need to raise the age of retirement in order to keep up. OECD had recently reported that the average woman and man can expect to live roughly 24 and 20 years beyond retirement age respectively, up from 20 and 17 years in 2010. At the same time, retirement ages across many countries have stayed the same. Among Asean countries, Singapore has the highest retirement age with 62 while Indonesia the shortest (57 years old).

Literature review

Hagen (2018) had estimated the health effects of increasing the normal retirement age using Swedish administrative data on drug prescriptions, hospitalizations, and mortality. By estimating the effect of the reform on individuals’ health within the age range 65–69, the results show no evidence that the reform impacted mortality or health care utilization. Increasing the normal retirement age may thus have positive government income effects without seriously affecting short to medium run government health care expenditures.

Meanwhile, Gough et al. (2008), in a study on the relationship between pension reforms, retirement age, pay and decision had concluded that in both countries Italy and the UK, high income earners retired relatively early. On the same note, the lowest income earners group tend to retire later. This is quite typical as the lower income group needs to work longer to support family, work longer due insufficient retirement savings, obligation to pay outstanding loans, and fear about the loss of future income. The research had also concluded that while the Italian’s retirement system emphasis on the state pension, the UK puts greater focus on private savings on the increase of retirement age.

On the other hand, Bovini and Paradisi (2019) had concluded that substitutability among different types of workers may affect the impact of public policies by creating labor demand spillovers within firms. The study found that older workers delaying retirement and younger co-workers are substitutes. Labor demand spillovers cause almost the entire short-run fiscal cost of the pension reform and therefore concluded that firm’s behavior and labor substitutability have important implications for the impact of policies that lower the turnover of older workers.

In addition, Vogel et al. (2013) suggested that an endogenous human capital formation coupled with an increase in the retirement age has strong implications in aggregate economic and welfare of society, particularly in an open economy. The demography study has been done in three countries in Europe namely Germany, France and Italy. High numbers in endogenous human capital and higher retirement age could help to sustain the economy as it can avoid a sudden shock in consumer spending and collection of taxes.

Scharn et al. (2018) meanwhile summarized that there is a wide range of determinants that influence retirement timing in modern industrialized countries. These determinants are differing across the countries. There are mainly eight domains influencing retirement timing namely demographic, healthcare, social status, types of job, financial factors, retirement preference and macro effects. Demographics factors will mainly explain how does age and sex play a role in retirement funding patters. Healthcare meanwhile symbolises two components, the purchase of healthcare related insurance for retirement and the life-expectancy of the retirees. On the same note, the social status and participation explains the level of respect, honor, competencies of a person in group of people, organization and society. The types of job meanwhile will also determine the retirement age. High-risk- high-pay job might cause a person to retire early. Furthermore, the financial position is considered the most important in deciding retirement age. Total amount of savings, investment, current and future commitments are in mind of many future-to-be retirees. In addition, the retirement preference could also a role. Hypothetically, a successful Muslims tend to retire early as many are preparing to spend time to perform Hajj and charity activities. As for macro effect, the country’s policies and economic factors such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP), employment rate, inflation rates become a key determinants towards deciding retirement age.

Ivanova et al. (2017) studied the impact of the increase in retirement age on labor supply and economic growth in Russia. Combining own estimates of labor participation and demographic projections by the Rosstat, the authors predict marked fall in the labor force (by 5.6 million persons over 2016 to 2030). Labor demand is also expected to go down but to a lesser degree. If vigorous measures are not implemented, the labor force shortage will reach 6% of the labor force by the period end, thus restraining economic growth. Even rapid and ambitious increase in the retirement age (by 1 year each year to 65 years for both men and women) can only partly lessen the adverse impact of demographic trend.

Domonkos (2015) in a study has concluded that in the case of increasing life expectancy, defined‐contribution schemes that apply actuarial formulae linking the level of starting monthly pension benefits to life expectancy are more useful in promoting a higher retirement age than conventional defined‐benefit schemes, which typically do not forge an automatic connection between longevity and starting pensions. Thus, the increase of retirement age subjects to the defined-contribution of the workers to the firms.

Problem Statement

A recent proposal from the Malaysian Trades Union Congress for Malaysia (MTUC) to increase the retirement age has sparked many debates among Malaysians. Even though the Prime Minister has shot down the proposal, there was no academic discussions made to provide comprehensive factual and numerical justifications over the decision. This paper therefore triggers researcher to probe the government’s fiscal implications, youth employment as well as demography and health analysis if the retirement age were to increase to 65.

Research Questions

The research and analysis would descriptively clarify a few questions namely 1. Will the increase of retirement age thwart the government’s fiscal policy? 2 Does the Malaysians are healthily fit for higher retirement age? and 3. Can our economy absorb the new graduates if the retirement age increase?

Purpose of the Study

The research and analysis would definitely attempt to examine the implications of increasing the retirement age from perspective of the government’s fiscal policy, Malaysians health level as well as the youth employment.

Research Methods

A trend analysis is adopted which canvasses several financial and economics’ indicators provided by Bank Negara Malaysia, Department of Statistics, Ministry of Education and Ministry of Finance, The World Factbook and other relevant sources. Adopting Sibin Sabu’s (2015) retirement age setting methodology, the research explore

Findings

Demography & Health

Demography analysis is a branch of study of statistics such as births, deaths, income, or the incidence of disease, which illustrate the changing structure of human populations. Based on the data sourced from CIA Factbook, Singapore has the highest retirement age in the South East Asia region with 62 and life expectancy of 82.9 while Indonesia has the lowest retirement age with 57 and life expectancy of 69.3. On average, the retirement age and life expectancy in the region are 54 and 66 respectively. The retirement age and life expectancy for Malaysia meanwhile 60 and 75.3 respectively (see Figure

On the same note, Singapore has the highest life expectancy to retirement age ratio. It indicates that the Singapore retirees have the longest life after their retirement. On average, they live about 20.9 years after retirement. Despite having been working for longer time due to high retirement age, enjoyed their retirement longer than other retirees in the region. It is also giving a sign that the people of the country have a better health status. On the other hand, Myanmar has the lowest retirement age to life expectancy ratio. The retirees in the country only live 6.8 years after retirement. As for Malaysia, the retirees have 15.3 years of life after retirement, 3.4 years higher than 11.9 years average for ASEAN countries. Surprisingly, the lower Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita countries such as Thailand and Vietnam have a higher life expectancy as compared to Malaysia. The correlation between retirement age and health status jives with Ilmakunnas and Ilmakunnas (2018) regression analysis which concluded that the health status is positively correlated with both actual and anticipated full-time retirement age.

The most aging country in Asean, based on median age, is Thailand with 38.1. On the other hand, the youngest country is Laos with a median age of 23.7. Only 6.8% of the country’s population or 7.2 million are aged above 60. As for Malaysia, the population with age above 60 is 11% or 3.5 million with a median age of 28.7 and ranked at 5th place in the region. In total, there are 71.6 million of population aged 60 and above in Asean.

Based on the life expectancy, life expectancy to retirement ratio and median age, the retirement age of 60 for Malaysians are considered fair. It should be noted that Japan is the most aging country in the world with median age of 47.7 and life expectancy of 84.3. The country’s retirement age however set at 60.

Youth unemployment

Employers and manufacturers disagreed on increasing the retirement age to 65 as it will thwart the recruitment of younger labour into the job market, according to Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers president Datuk Soh Thian Lai. In addition, based on Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) (2019) report, from 2010 to 2017, the number of tertiary graduates entering the job market has surpassed the number of jobs created for them. During the period, there were 173,457 diploma and degree graduates generated by the universities annually whereas there were only 98,514 high-skilled jobs offered. This left 74,943 graduates to work in the sector that is not compensable with their qualifications. The situation is caused by slower economic growth which in turn has not created sufficient high-skilled jobs to absorb the graduates. Based on simple regression analysis, Malaysia’s economic needs to grow by 9.0% annually in order to absorb the 74,943 graduates or otherwise they will end up working in the gig economy. According to Employees Provident Fund (EPF), the gig economy rose by 31% a year, faster than the traditional job market. Furthermore, Khazanah Research Institute (KRI) in a report has concluded that one-third of young workers are turning to non-standard employment such as freelancing of which it offers limited access to labour and social protection. On the same note, Malaysia has already registered high youth unemployment rate of 13.2 per cent in 2017. It was three times higher as compared to the national unemployment rate. In addition, the unemployment rate among the youth between 15 and 24 has been hitting double digit since 2012. It was recorded 10.6 per cent in 2016. Lack of job experience, education and insufficient skills are among the factors that contributed to the high unemployment rate.

Most of the jobs created in 2018 were in the unskilled and low-skilled category. BNM report has also stated that graduates with master degree’s starting salary decreased from RM2,923 in 2010 to RM2,707 in 2018. On a similar note, diploma holders’ starting salary shrank from RM1,458 to RM1,376 over the same period (annual inflation factored in). On the other hand, according to JobStreet survey, 67 per cent of employers who took part in a 2017 reported that the graduates have asked for unrealistic wages of between RM2,400 and RM3,000 a month.

All in all, there are still many of young graduates are waiting to be employed. Extending the retirement age will deny them from entering the labour market after so many years of time, efforts and money consumed in the university. The extension of retirement age could also elevate the cost of doing business. Higher premiums of insurances for healthcare are also expected.

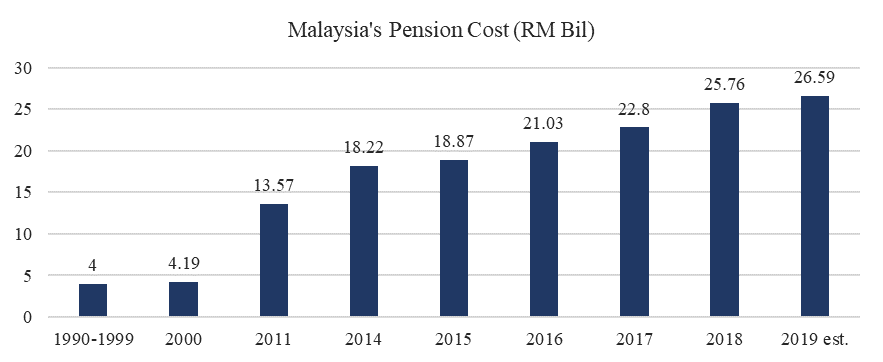

Fiscal burden

According to Ministry of Finance in a Treasury Economic Outlook 2019 report, from 1990-1999, the annual cost of Malaysia’s pensions and gratuities were below RM4 billion. It has reached to RM4.19 billion a year later. It has been skyrocketed to RM13.57 billion in 2011, in just 10 years. In 2014, it has ballooned to RM18.22 billion and increase further to RM 18.87 billion in 2015. The pension costs have breached RM 20 billion mark to RM21.03 billion in 2016 in the span of five years from 2011. In 2017, it grew to RM22.18 billion. As for 2018 and 2019, it has been estimated to be RM25.76 billion and RM26.56 billion respectively. Within 20 years, the pension costs have increased about six times higher or at compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.8 per cent. Thus, the higher-than-expected pension cost seems uncontainable and possibly affecting the government’s fiscal budget in the future. Judging from a CAGR of 9.8 per cent, the pension cost will balloon to RM 46.6 billion in 2025.

As percentage of government revenue, the pension cost is expected to increase to 10% in 2020 from 7% in 2014. On a similar note, the percentage of pension cost to government’s operating expenditure is expected to increase to 12.1% next year from 8.3% in 2014. Going forward, the higher contribution of pension cost is highly due to lower government revenue for the year.

In managing pension cost, the government seems having difficulties in cutting it down. Making retirement compensation lower to the current government servants is just impossible. The only way for the government to contain the pension cost is by “not to add more costs” into it and this can be done by not extending the retirement age.

Conclusion

From demography and health perspective, despite Malaysians are now have longer life expectancy age, it is still relatively lower as compared to our neighbouring countries. Brunei, Vietnam and Thailand maintain its workers’ retirement age at of 60 in spite of higher life expectancy. Judging from this situation, Malaysia is recommended not to extend the retirement age.

On the same topic, from the youth employment’s perspective, it strongly suggested that the retirement should stay at 60 or otherwise the country must grow its economy by 9.0 per cent annually in order to absorb unemployed graduates.

On another note, increasing the retirement age would not have positive fiscal impact to the government. The pension costs have ballooned from less than RM 4 billion in 1990- 1999 to 25.76 billion in 2018. The government should focus on creating more jobs for new generation and propelling the economics by investing towards advance technology.

As for conclusion, it is recommended that the government not to proceed for higher retirement age and let the market forces to decide. In case shortage of expertise in particular sector, the firms or corporates may opt to reemploy them but on a voluntary basis as per company’s demand and workers’ contributions.

References

- Bank Negara Malaysia. (2019). Monthly Highlights and Statistics. https://www.bnm.gov.my/index.php?csrf=5562173c9038e86e932e10d8d002a36d10d3db9b&ch=en_publication&pg=&pub=msbarc&yearfr=2019.

- Bovini, G., & Paradisi, M. (2019). Labor substitutability and the impact of raising the retirement age. Scholar Harvard.edu. https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/5d8e3657fd776a7142924af1/5d926005b46 207e6b0f249ed_bovini_paradisi_sep2019.pdf

- Domonkos, S. (2015). Promoting a higher retirement age: A prospect‐theoretical approach. International journal of social welfare, 24(2), 133-144.

- Gough, O., Adami, R., & Waters, J. (2008). The effects of age and income on retirement decisions: A comparative analysis between Italy and the UK. Pensions: an International Journal, 13(3), 167-175.

- Hagen, J. (2018). The effects of increasing the normal retirement age on health care utilization and mortality. Journal of Population Economics, 31(1), 193–234.

- Ilmakunnas, P., & Ilmakunnas, S. (2018). Health and retirement age: comparison of expectations and actual retirement. Scandinavian journal of public health, 46, 18-31.

- Ivanova, M., Balaev, A., & Gurvich, E. (2017). Implications of higher retirement age for the labor market. Voprosy economiki, 3.

- Ministry of Finance Malaysia. (2019). Economic Outlook. https://www.treasury.gov.my/pdf/economy/2019/chapter3.pdf

- Scharn, M., Sewdas, R., Boot, C. R., Huisman, M., Lindeboom, M., & Van Der Beek, A. J. (2018). Domains and determinants of retirement timing: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. BMC public health, 18(1), 1083.

- Sibin Sabu. (2015). Setting an Ideal Retirement Age! Centre for Public Policy Research (CPPR). https://cppr.blogspot.com/2015/03/setting-ideal-retirement-age.html

- Vogel, E., Ludwig, A., & Börsch-Supan, A. (2013). Aging and pension reform: extending the retirement age and human capital formation (No. w18856). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 December 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-099-0

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

100

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-905

Subjects

Multi-disciplinary, accounting, finance, economics, business, management, marketing, entrepreneurship, social studies

Cite this article as:

Abdullah, Z. (2020). Higher Retirement Age? Trend And Growth Analysis Of Labour Market In Malaysia. In N. S. Othman, A. H. B. Jaaffar, N. H. B. Harun, S. B. Buniamin, N. E. A. B. Mohamad, I. B. M. Ali, N. H. B. A. Razali, & S. L. B. M. Hashim (Eds.), Driving Sustainability through Business-Technology Synergy, vol 100. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 583-591). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.12.05.63