Abstract

Although it is universally known that the success of adaptation of junior staff members to the penal system environment influences their whole further career, specific characteristics of adaptation to working conditions in law enforcement agencies in general and in penitentiary establishments in particular have not been sufficiently studied yet. The research was conducted in four stages (N=295): desktop analysis, ascertaining experiment, forming experiment and data analysis. The research comprised theoretical methods in the form of an analysis of literature on psychology and education and compilation of the findings, empirical methods in the form of an ascertaining and a forming experiment, testing and an analysis of documents and personnel records, and psychodiagnostic methods in the form of the Prediction technique used to evaluate mental toughness and the risk of disadaptation under stress developed by the Kirov Military Medical Academy, and Gerchikov's Labour Motivation Test. The statistical analysis of test results was conducted with the application of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test in the IBM SPSS Statistics software. A special training programme was used as the main method of correction (10 meetings of 40-50 minutes twice a week). The purpose of the correction was to relieve mental strain and improve labour motivation in adaptation to working conditions. The training resulted in higher average levels of emotional stability, normative behaviour, hardiness and diplomacy as well as in lower levels of aggressiveness, intemperance, suspiciousness, anxiety, conservatism, conformity and slackness. Moreover, the average self-esteem became more adequate.

Keywords: Adaptabilityjunior stafflabour motivationmental toughnesspenal systempersonal qualities

Introduction

The need to adapt to constant changes in the social, economic, technical and technological spheres has affected the labour market in such a way that today counselling support must be considered as an investment into human resources as it can generate multiple benefits for organizations as well as for employees and their personal job satisfaction.

The study will include such aspects of adaptation as adaptability, or the property of a system to adapt to possible changes in the environment (used to define adaptability of the system), adaptation as the adapting of an adaptive system (used to define the process of adaptation), and adaptation as the method based on the processing of incoming information and used to achieve a certain degree of optimization (used to define adaptation algorithms). If there are systems that use adaptability to further when new features or changes occur, such models should be referred to as adaptive (Aksenova & Aksenova, 2017).

Counselling support within adaptive systems must include determination of existing concepts for various hierarchical levels, an analysis of current needs in staff training, development of continuing education programmes that follow adult learning principles, definition of objectives, content, methods and tools of learning for a particular job, and implementation of specific performance measurements (Sosnina, 2010; Udrea, 2014; Voloshin, 2016).

Successful adaptation of junior staff members to specific working conditions from the very first years of employment may prevent emotional and professional burnout that is inevitable for specialists of caring professions. These also include staff members of the penal system that interact with convicted persons directly or through other staff members.

International human rights law provides comprehensive protection to detainees, in particular by means of the absolute prohibition of torture and other forms of inhuman treatment, and through ensuring their right to human dignity. However, there is a significant gap between what should be done considering respect for human rights and what is actually done. We can only hope that the growing interest in human rights and the expanding knowledge on the topic will result in further protection of detainees’ rights in order to ensure that those people who often get forgotten by society can enjoy a dignified existence. The cited work provides a review on the worldwide detention policy, main rights granted to detainees, in particular the prohibition of torture and inhuman treatment, and existing safeguards to protect their rights and key international control mechanisms (Birk & Kiselica, 2015).

In international practice, penitentiary facilities are a branch of the criminal justice system that is responsible for probation, imprisonment, control, rehabilitation, medical care, parole and sometimes execution of convicted criminals. It involves a wide range of specialists, including wardens, sheriffs, jail officers, prison guards, corrections investigators, probation officers, parole officers and administrative support staff. The works cited here focus on responsibilities of corrections personnel working directly with convicted persons, especially of personnel that interact with detainees and supervise and control detainees, prisoners and convicts. Unethical behaviour of corrections staff largely includes inhuman treatment of prisoners, abuse, providing prisoners with contraband, and sexual exploitation (Torres & Turvey, 2013).

Despite a growing number of studies on the topic, an important but mostly understudied question remains the extent to which a country's penal policy and its punitive actions are actually reflected in prisoners’ experiences. Based on the analysis of the way prisoners perceive correctional officers’ behaviour in English and in Dutch prisons, some conclusions have been drawn on significant differences in relationships between staff and prisoners. In English prisons, relationships between staff and prisoners are more detached, and staff members seem to be unresponsive. In Dutch prisons, staff is perceived as more helpful and fair. It was found that changes in the penal policy are not necessarily mirrored in the practice of prisons (Dirkzwager & Kruttschnitt, 2012). However, even a step towards changes can result in more successful adaptation of staff members and especially of junior staff.

It is expected that citizens tend to view corrections staff negatively if a country’s prison system is working against the people (Harris, 2010; Szczepanik et al., 2014). Corrections staff experience excessive stress that leads to physical illnesses, emotional burnout, family problems and failures to exercise their duties, which in turn adds more pressure on other staff members and compromises institutional security (Moon & Maxwell, 2004).

Even if all standards of institutional security are met, the penal system still can influence adaptation of junior staff members through its specific characteristics that include a clearly defined structure and regulation of official activities, the need to strictly follow national legal acts and comply with the rule of law, a stressful nature of official activities and their impact on the security and the quality of life, specific characteristics of the subculture of corrections officers, and some others (Belicheva, 2012).

Adaptation of junior staff members to working conditions in law enforcement agencies in general and in penitentiary establishments in particular has some specific characteristics.

First of all, the process of adaptation undergoes several steps. According to works by other researchers, there are four steps: diagnosis, introduction, adaptation and evaluation. In this regard, counselling support must be provided to junior staff members not only within these steps but also further into their professional careers.

Researchers believe that mentors and psychologists play a leading role at each step as they accompany junior employees during a truly difficult period of their professional development and make it possible for them to acquire knowledge, skills and competences necessary for handling their professional tasks without spending their own inner resources.

However, no matter how effective and intense the training is that is performed with junior staff members on site in order to assist them in adaptation to working conditions in the penal system environment, it might be useless unless an employee displays favourable individual characteristics.

Many works have been devoted to the problem of the impact of one`s individual characteristics on their choice of career and on the nature of their further professional development (Ivanova, 2008; Johnson, 2016; Malkina-Pykh, 2005). One work used results of the Prison Social Climate Survey, which is administered to a sample of all employees in the federal prison system. The study revealed that blacks and whites and Hispanics and non-Hispanics did not differ in their job satisfaction or their opinions about supervision. Both blacks and Hispanics had a greater sense of personal efficacy in working with inmates, and blacks reported less job-related stress (Wright & Saylor, 1992).

Adaptation of corrections officers, besides one`s individual characteristics and personality traits, is also influenced by general age-specific characteristics of the emerging adulthood period (usually from 20 to 27 years).

The emotional component of interpersonal relations is particularly significant during this period; it defines values of a person and feelings they have regarding their objectives, activity and behaviour. Self-recognition, self-acceptance, positive self-evaluation, independence and self-confidence assume particular relevancy at this age period (Demidov & Mokhorov, 2018; Shipunova & Berezovskaya, 2018).

It is believed that only high-quality professional selection and further motivation (financial and non-financial) of employees to conscientious performance of their official duties, together with their aspiration to work in the penal system, can generate the expected results and minimize failures of duty.

A predominant role of assisting junior staff members in their professional development is given to psychologists, mentors and master trainers. It also should be noted that due to the above-mentioned age-specific characteristics, it is important for a junior employee to see that their mentors, managers and colleagues trust their competences and skills.

Professional development is associated with the formation of a positive attitude towards a chosen profession, aspiration to self-improvement and acquisition of a professional identity, and improvement of profession-related qualities and skills. It also requires the teaching of junior staff members self-regulatory skills for mental toughness and confidence building in order to realize motives of self-recognition and self-acceptance. It is also important to establish and maintain an atmosphere of unity and harmony within the team to help junior members adapt and feel accepted (Korzhova, 2015).

The success of adaptation is judged according to external (the degree of adaptation) and internal (the degree of subjective well-being) criteria. However, there have been attempts to establish a third criterion (a systematic one) that would describe interaction between the personality and the environment. We believe that the degree of integration of profession-related qualities can be viewed as such a criterion. It is reflected in individual characteristics and personality traits of junior penal staff, their mental toughness, risk of disadaptation under stress and types of labour motivation.

Problem Statement

Although it is universally known that the success of adaptation of a junior staff member to the penal system environment influences their whole further career, specific characteristics of adaptation to working conditions in law enforcement agencies in general and in penitentiary establishments in particular have not been sufficiently studied yet.

Research Questions

3.1 To analyse individual characteristics and personality traits of junior penal staff and identify the nature of changes occurring in the training process;

3.2 To analyse mental toughness and a risk of disadaptation under stress before and after the training;

3.3 To analyse types of labour motivation before and after the training.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study is to determine on the basis of theoretical arguments the efficiency of a special training programme in adaptation of junior staff members to the penal system environment and prove it with an experiment.

Research Methods

The empirical study in the form of an ascertaining experiment focused on adaptation of junior staff to working conditions in the penal system environment at the Russian federal penal enforcement institution of the Chelyabinsk region.

The purpose of the study was to determine on the basis of theoretical arguments the efficiency of a special training programme in adaptation of junior staff members to the penal system environment and prove it with an experiment.

The study deals with adaptation of junior staff members, in particular it examines counselling support provided to junior staff members in their adaptation to the penal system environment.

The research on adaptation was conducted in four stages.

Desktop analysis: an analysis of literature on psychology and education dedicated to the problem of adaptation of junior staff members to the penal system environment.

Ascertaining experiment: psychological and pedagogical testing of adaptation of junior staff members to the penal system environment and processing of experimental results.

Forming experiment: an experiment on the role of counselling support in adaptation of junior staff members to the penal system environment and processing of experimental results.

Data analysis: an analysis of findings and study results, statistical and qualitative analyses of the obtained data, systematization of results, the drawing of conclusions, and hypothesis testing.

The study incorporated a wide range of methods and techniques, in particular theoretical methods in the form of an analysis of literature on psychology and education and compilation of the findings, empirical methods in the form of an ascertaining and a forming experiment, testing and an analysis of documents, and psychodiagnostic methods in the form of Prediction technique used to evaluate mental toughness and the risk of disadaptation under stress developed by the Kirov Military Medical Academy, and Gerchikov's Labour Motivation Test. The statistical analysis of test results was conducted with the application of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test in the IBM SPSS Statistics software.

The study was conducted at the Russian federal penal enforcement institution of the Chelyabinsk region (N=295, among them there were 14 junior staff members who participated in the training).

Findings

The special training programme comprised 10 meetings of 40-50 minutes held twice a week. The training included tasks of introduction, the main tasks and tasks for self-reflection. Some tasks were done regularly and almost at every meeting (Introduction, Reflecting on the meeting, Host`s summary, Goodbye), therefore they are not mentioned in every meeting.

I. Goal: to establish favourable conditions for teamwork, to introduce rules and principles of the training, to learn an active communication style and means of transmitting and receiving feedback. Tasks: Rules in Our Group, Relieving Muscular Tension and Releasing Voice, Dictionary of Emotions, Who Am I?

II. Goal: to improve teamwork and self-reflection skills. Tasks: Letter to Myself About Goals of Participation in the Training, Motivation to Study and Realization of Personal Work Experience; Finding Personal Interests.

III. Goal: to improve communication and teamwork skills. Tasks: Funny Experiment, Same as a Ball, Detectives (word-for-word repetition of remarks said by a partner), Self-Control of External Expression of Emotions, Mirror (improvement of facial expression control).

IV. Goal: to improve empathy and verbal and non-verbal communication skills. Tasks: Dictionary of Emotions Competition (verbalization of emotional states), Fishing Cork in an Ocean (self-control in conflicts), Adjustment (establishing trust with a partner through mirroring intonations and a speech tempo), Cat in a Bag (improving skills of persuasion), Narrow Bridge (development of behavioural patterns of competition, cooperation, compromise and adaptation).

V. Goal: to establish skills of a positive exchange of information, to improve self-esteem and to develop non-verbal communication skills. Tasks: Compliments, My Acts of Kindness, Crocodile (non-verbal communication), External Expression of Emotions, Pump and Ball (relieving muscular tension).

VI. Goal: to self-reflect and to improve decision-making skills and teamwork skills. Tasks: My Personality Traits (self-reflection), Traffic Lights (teamwork), I am Strong – I am Weak (my strong and weak qualities).

VII. Goal: to improve skills of constructive communication and establish objective self-esteem. Tasks: Compliments, Wood Chips in a River (establishment of a calm and honest atmosphere in communication, constructive communication), Straight Talk (objective assessment of personal communication skills, feedback from the group), Hot Potato of Complainers (a communication game)

VIII. Goal: to improve listening skills. Tasks: Passive Listening (to demonstrate inefficiency of transmitting information without feedback), Active Listening (with feedback), Three Circles (discussion of a personal life cycle), Universe of Me (realization of self-worth), Metaphor (improvement of conversation and discussion skills).

IX. Goal: to improve conversation and self-presentation skills and creative potential. Tasks: Rumpus (non-verbal transmission of information), Learning from Our Mistakes (conversation and self-presentation), Understanding Career (realization of potential, improvement of communication skills), My Style of Decision-Making.

X. Goal: to improve skills of developing personal career potential and managing personal career, to improve communication skills and to draw conclusions of the training. Tasks: Conversation on Goals and Career with Feedback (designing personal professional growth), Seven Bogatyrs (enhancing communication skills, skills of finding arguments for personal opinions and self-presentation skill), Couple Drawing (improving self-regulation, behaviour, skills of following the rules and constructive cooperation skills), Letter to Myself (drawing a conclusion on the experience received in the training and analysing personal progress).

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used in the study to prove the study hypothesis that following the implication of the training programme as a method of counselling support in adaptation of junior staff members to the penal system environment, their level of adaptation and adaptation-related personal characteristics might improve. This is a non-parametric test that is applied for comparison of two independent samples (Shelekhova, 2015).

The results of statistical analyses of each of the performed psychodiagnostic methods are presented next to test the hypothesis.

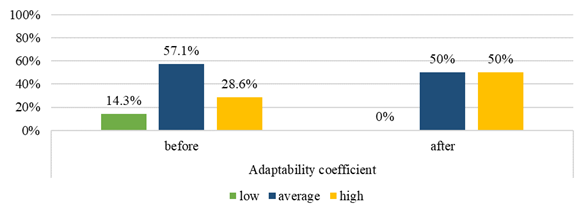

Figure

The results show that equal numbers of the junior employees demonstrate a high and an average level of adaptability after the programme; low adaptability is not observed found. Thus, following the implementation of the adaptation training programme, a larger number of junior employees showed a stronger adaptability.

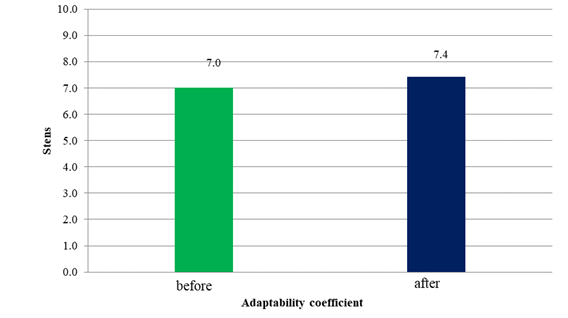

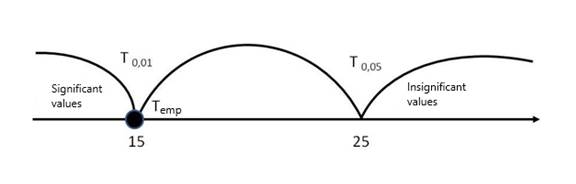

However, median values of adaptability among the employees have not changed, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test did not determine any significant changes (Figure

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test on adaptability

Тemp=50

Critical values of T, n=14:

0.01 = 15

0.05 = 25

The obtained Тemp on adaptability is deemed insignificant.

The obtained Тemp on adaptability is deemed insignificant (figure

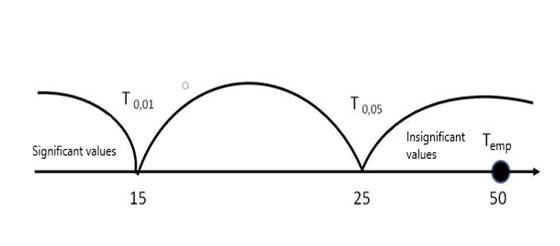

Figure

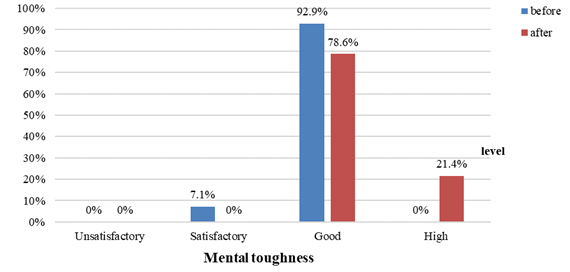

The results on mental toughness before and after the programme show that no one among the junior staff members has either unsatisfactory or satisfactory levels of mental toughness. 78.6% of the subjects demonstrate a good level of mental toughness and 21.4% – a high level. Thus, it can be predicted that all junior staff members will display a low probability of mental disturbances and a high level of behavioural reaction as well as adequate self-esteem and evaluation of the environment.

Next, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test will be applied to compare the results on mental toughness before and after the implementation of the programme.

Тemp=15

Critical values of T, n=14:

0.01 = 15

0.05 = 25

The obtained Тemp on mental toughness is deemed significant.

The obtained Тemp=15 is within significant values (p< 0.01) (Figure

Figure

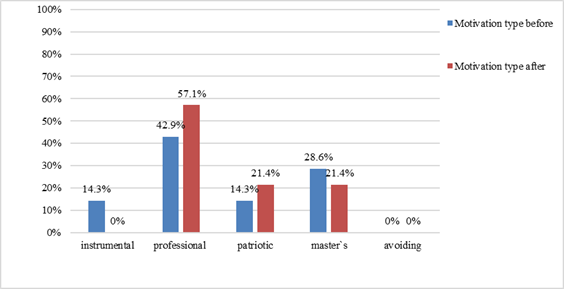

As seen in the figure

The Dutch penal system also views the professional type of labour motivation as one of the key factors that lead to establishment of a decent and humane climate in prisons that encourages prisoners to assume responsibilities and change their life. Prison staff is seen as the most significant factor in achieving this objective as it is believed that their work environment influences the way they treat prisoners, which in turn has an impact on their perception of prison conditions. Establishment of a good work environment for penal staff is essential for practising an active approach to prisoners (Molleman & Broek, 2014).

The patriotic type of labour motivation was found in 21.4% of the employees after the programme implementation. They enjoy high moral, religious or ideological views and believe to be necessary for the organization. These employees are willing to work at full capacity, value results of the common cause they are participating in and want to be acknowledge for their participation through moral appraisal and rewards. Other empirical studies revealed that positive representations of prison wardens depict them as friendly men of a strong character, who embody and command respect for authority (Dolgova et al., 2019; Tabolina & Gulk, 2018; Walby et al., 2018).

The master`s type of labour motivation was found in 21.4% of the subjects. These employees are willing to assume responsibility for their work and do their best without asking for a more interesting task or for higher wages. They do not need to be given additional instructions or to be under constant control. The instrumental and avoiding types of labour motivation were not displayed by any of the subjects after the training.

Therefore, following the implementation of the training programme as a method of counselling support in adaptation of junior penal staff members, significant changes occurred in personal traits and mental toughness of the employees.

Another empirical study was performed that focused on reputations of cadets studying at educational establishments of the Federal Penitentiary Service. The purpose of the study was to identify factors that might lead to the establishment of either a positive or a negative reputation of an aspiring penal establishment staff member. As proven by the study, there is a correlation between reputations of the Federal Penitentiary Service cadets and such personality traits as self-discipline, motivation for self-learning and self-development, anxiety, impulsiveness and intelligence. Findings obtained in the studying of 275 first-year cadets of the Academy of the Russian Penitentiary Service are presented in the current study as well. It was found that the personal reputation development of aspiring officers of the Russian Penitentiary Service facilities is influenced by the reputation of the commander of a cadets training unit, his self-discipline, motivation for self-learning and self-development, anxiety and impulsiveness. The conclusion was drawn that the educational process during the first year at educational establishments of the Federal Penitentiary Service does not adequately address the problems of improving skills of establishing and maintaining a positive reputation in cadets, which in the further course seriously hinders their professional development (Gavrina et al., 2018).

Conclusion

The study showed that the training programme helped junior penal staff members positively improve emotional stability, normative behaviour, hardiness and diplomacy and decrease the level of aggressiveness. In general, the junior employees have become less intolerant, suspicious, anxious, conservative, conformist and slack; their self-esteem has become more adequate.

Following the programme, the equal numbers of the employees demonstrated either average or high adaptation; low adaptation was not found in the subjects. Moreover, neither unsatisfactory or satisfactory levels of mental toughness were demonstrated. 78.6% of the employees displayed a good level of mental toughness and 21.4% – a high level.

The professional type of labour motivation was exhibited by more than half of the employees (57.1%), while the patriotic and the master`s ones were shown by the rest of the subjects in equal parts (21.4%). Neither the instrumental nor the avoiding types were found.

The statistical analysis of the test results revealed that significant changes occurred in personality traits and mental toughness of the subjects.

Based on the obtained findings, recommendations on preventive and corrective measures for adaptation of junior staff members were given together with a plan of programme implementation.

In the further study, it is possible to continue the work on improving adaptation of junior staff members through target cooperation with all participants of the process, in particular with supervisors, mentors, psychologists and personnel and training staff.

Acknowledgments

The article is written in the framework of the Scientific and Methodological Foundations of Psychology and Management Technology of Innovative Educational Processes in the Changing World scientific project of the comprehensive plan of research, project and organizational activities of the research centre of Russian Academy of Education in the South Ural State Humanitarian Pedagogical University for 2018-2020 (Grant from the Mordovia State Pedagogical Institute named after M. E. Evsevyev).

References

- Aksenova, G. I., & Aksenova, P. Yu. (2017). The problem of personality adaptation in domestic psychology. Applied Legal Psychology, 4, 28–36. [in Rus.]

- Belicheva, S. A. (2012). Preventive psychology in preparation of social teachers and psychosocial workers. Piter.

- Birk, M., & Kiselica, E. (2015). Detention: Legal Framework for the Care of Those in Detention and the Prohibition/Prevention of Torture, Cruel, Degrading or Inhuman Treatment. In R. Byard, & J. Payne-James (Eds.) Encyclopedia of Forensic and Legal Medicine (p. 236-243). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800034-2.00141-5

- Demidov, V., & Mokhorov, D. (2018). Professional Culture Of A Specialist In The Field Of Jurisprudence. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences, LI, 932-942. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.12.02.101

- Dirkzwager, A. J. E., & Kruttschnitt, C. (2012). Prisoners’ perceptions of correctional officers’ behavior in English and Dutch prisons. Journal of Criminal Justice, 40(5), 404-412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2012.06.004

- Dolgova, V., Rokitskaya, Ju., Bogachev, A., & Nurmiev, G. (2019). Characteristic aspects of professional self-determination in students of pedagogical college. Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, 90, 14–16. https://doi.org/10.2991/ispcbc-19.2019.4

- Gavrina, E. E., Aksenova, G. I., Kovalchuk, I. A., & Tyugaev, N. A. (2018). An empirical study of the cadets' reputational orientations. Psychological Science and Education, 23(5), 67-76. https://doi.org/10.17759/pse.2018230507 [in Rus.]

- Harris, C. J. (2010). Problem officers? Analyzing problem behavior patterns from a large cohort. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38(2), 216-225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010.01.003

- Ivanova, I. L. (2008). Professional'naya identichnost' v sovremennyh issledovaniyah [Professional identity in modern research]. Questions of Psychology, 1, 89–101. [in Rus.]

- Johnson, M. (2016). Relations between explicit and implicit self-esteem measures and self-presentation. Personality and Individual Differences, 95, 159–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.02.045

- Korzhova, O. V. (2015). On the psychological support of the professional development of young employees of the special purpose department. Sheets of the penal system, 6, 11-14. [in Rus.]

- Malkina-Pykh, I. G. (2005). Age crises of adulthood. EKSMO. [in Rus.]

- Molleman, T., & Broek, T. C. (2014). Understanding the links between perceived prison conditions and prison staff. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 42(1), 33-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2014.01.001

- Moon, B., & Maxwell, S. R. (2004). The sources and consequences of corrections officers' stress: A South Korean example. Journal of Criminal Justice, 32(4), 359-370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2004.04.006

- Shelekhova, L. V. (2015). Mathematical methods in psychology and pedagogy. Doe. [in Rus.]

- Shipunova, O. D., & Berezovskaya, I. P. (2018). Formation of the specialist's intellectual culture in the network society. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences EpSBS, LI, 447-455. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.12.02.48

- Sosnina, V. N. (2010). Features of the socio-psychological adaptation of employees to service in the penal system. Bulletin of the Buryat State University, 1, 143–145. [in Rus.]

- Szczepanik, R., Simpson, G., & Siebert, S. (2014). Prison officers in Poland: A profession in historical perspective. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 47(1), 49-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2014.01.002

- Tabolina, A. V., & Gulk, E. B (2018). Gaming Technologies As A Mean Of Development Of Motivation Of Students. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences EpSBS, LI, 1672-1678. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.12.02.179

- Torres, A. N., & Turvey, B. E. (2013). Ethical Issues for Corrections Staff. In B. E. Turvey & S. Crowder (Eds.), Ethical Justice (pp. 377-401). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-404597-2.00012-7

- Udrea, C. (2014). Pedagogical Strategies for Continuous Training in the Police. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 142, 597-602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.07.672

- Voloshin, D. V. (2016). Historical and pedagogical heritage of N.F. Luchinsky. Education and Science, 6(135), 187-199. https://doi.org/10.17853/1994-5639-2016-6-187-199 [in Rus.]

- Walby, K., Piche, J., & Friesen, B. (2018). “…they didn't just do it because it was a job”: Representing wardens in Canadian penal history museums. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 53, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2017.12.002

- Wright, K., & Saylor, W.G. (1992). A comparison of perceptions of the work environment between minority and non-minority employees of the federal prison system. Journal of Criminal Justice, 209(1), 63-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2352(92)90035-8

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

18 December 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-097-6

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

98

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-788

Subjects

Communication, education, educational equipment, educational technology, computer-aided learning (CAL), Study skills, learning skills, ICT

Cite this article as:

Dolgova, V., Bogachev, A., Kryzhanovskaya, N., & Ufimtseva, A. (2020). Characteristics Of Adaptability Of Junior Penal Staff Members. In O. D. Shipunova, & D. S. Bylieva (Eds.), Professional Culture of the Specialist of the Future & Communicative Strategies of Information Society, vol 98. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 45-57). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.12.03.5