Abstract

The paper considers the problem of teacher-student interaction styles in the process of online foreign language teaching at a university. Taking into account the inevitable integration of online classes into education and the aim to enhance the students’ innovative potential the authors set the goal to determine and describe the efficient communication styles for a teacher to interact with students in the electronic environment. Literature review and theoretical analysis allowed the authors to specify in detail characteristics of authoritarian, democratic and laissez-faire styles, which are applicable to online English as a Foreign Language (EFL) instruction. The characteristics are based on the four criteria: determining the components of online learning process, organizing online group activities, giving the online feedback, making online assessment. Using the given characteristics, a questionnaire was created to group students’ preferences into three categories. To obtain necessary data about students’ preferences related to online teacher-student interaction styles a survey was conducted among the students of National Research University of Electronic Technology (MIET), Moscow, Zelenograd, Russian Federation. The results of the survey show that students tend to prefer a democratic EFL teacher to communicate with online. Modern students are eager to participate actively in the education process organized in the electronic environment. To take into consideration their point of view and, therefore, to make the process of online EFL learning more effective, the authors recommend that the teachers maintain the so-called “subject-subject” or partnership relation with their students.

Keywords: Teacher-student interaction styleselectronic environmentforeign language teaching

Introduction

As today we are facing the rise of an innovative economy, the aim of higher education institutions should be to mold University graduates of any profile into innovative personnel.

In a broad sense, the term “innovative personnel” refers to the employees with high innovative potential. Innovator is a creative worker, someone who introduces changes and new ideas, someone capable of thinking outside of the box and adapting to the rapidly changing conditions of the post-industrial society. Such persons are characterized by innovative thinking and behavior. They aspire to a high level of professionalism, try to constantly improve their qualifications and creative skills, eager to master the latest technological approaches, methods and forms of labor organization. Such specialists are ready for continuous self-improvement and acquisition of new competencies. Moreover, innovators should possess certain psychological and moral qualities – adaptability, flexibility of thinking, imagination, determination and so on (Evdokimova, 2020).

Given the speed of innovation happening in the world, it is very difficult to predict what hard skills (specific job-related abilities) an innovative person may need in the future. An innovative specialist should possess not only a set of learned competencies (which tend to become obsolete), but also exhibit the so-called soft skills (Fadel, 2015; Klaus, 2010). By the term “soft skills” we mean after Maria Cinque (2016) “a dynamic combination of cognitive and meta-cognitive skills, interpersonal, intellectual and practical skills. Soft skills help people to adapt and behave positively so that they can deal effectively with the challenges of their professional and everyday life” (pp. 394-395).

The currently prevailing classical/traditional educational paradigm, which sets the task of mainly transmitting information from the teacher to students, does not meet the needs of the present society, since the knowledge that is transmitted during the educational process becomes outdated very quickly, especially in high-tech fields.

Thus, in the new educational paradigm, the main task of the teacher should be to enhance the students’ autonomy (Moore et al., 2019), sense of responsibility (OECD, 2018), creativity and interpersonal communication skills, in other words, the teacher should help the students fulfill their innovative potential.

Problem Statement

To reform teaching and learning practices, teachers all over the world are trying to integrate information and communication technologies (ICT) into classrooms (Levy & Moore, 2018; Yang & Shadiev, 2019). Blended learning (“a combination of traditional f2f [face-to-face] modes of instruction with online modes of learning (OL), drawing on technology-mediated instruction, where all participants in the learning process are separated by distance some of the time” (Siemens et al., 2015, p. 62) is being widely used. On introducing blended learning into the process of education, teachers enhance the students' ability to plan and organize their study activities, prioritize daily tasks focusing on the result. The students learn to engage their problem-solving skills when making decisions / informed choices in challenging situations and feel responsible for them. Students have opportunities to autonomously find and analyze information, transform it into knowledge and present the obtained results using various modern technologies. Blended learning helps to organize controlled independent work of the students and creates the conditions for various modes of interaction – not only between the teacher and students, but also between students themselves, as well as between the teacher and the so-called “small groups” of students. Moreover, the function of the teacher is to train the interpersonal communication skills of the students (Evdokimova et al., 2018). These forms of interaction are possible both in the “brick-and-mortar” classroom and during extracurricular time in the electronic environment through webinars, chats, blogs, etc. We can use ICT to do all the conventional things we have always done in the classroom, in the same kinds of ways. But the focus of our research is the use of technology in innovative ways which will change the nature of the interaction between teachers and students.

Research Questions

There is a wide range of research worldwide concerning different aspects of teacher-student interaction. Some of the researchers study the impact of teaching styles on the psychological state of the students (Yao & Luh, 2019), the process of learning (Leithwood et al., 2010), students’ interest and achievement (Dever & Karabenick, 2011; Dinham, 2007), students’ motivation and engagement (Stroet, et al., 2013), student autonomy (Erdel & Takkac, 2019). Some findings show that interpersonal relations influence the students’ perception of the teacher competence (Clemente, 2018).

It is worth mentioning that there are no studies showing in what way the interaction between teachers and students in an online environment is different from that of the traditional classroom. Methodological decisions about the organization of online training are being made intuitively, since practical implementation of online education happens faster than its theoretical research. The impossibility of conducting face-to-face classroom activities during coronavirus pandemic has accelerated the process of reformatting teaching English as a Foreign Language (EFL) to university students. But are the teachers aware of specific online interaction techniques? And what do teachers know about students’ preferences related to online teacher-student interaction styles?

Purpose of the Study

Therefore, the urgent task of pedagogical science today is to determine and describe the efficient communication styles for a teacher to interact with students in the electronic environment.

Research Methods

To fulfill the task it is necessary first to study teacher-student communication styles in face-to-face teaching.

At present, the theory of teaching styles describing teacher-centered and student-centered communication patterns is rather popular. It favours the student-centered classroom interaction, when the teacher considers the students’ needs and interests, fosters their personality through managing their activities (Rogers, 1983).

As Jones states (2007), “in a student-centered class, the teacher is a member of the class as a participant in the learning process” (p. 2). For the student-centered interaction to be a success the teacher should establish good rapport with the students (Estepp & Roberts, 2015) and relationships of trust (Robinson, 2017).

Grasha (1996) gives a more detailed classification of teaching styles and differentiates between five of them.

Teacher-student interaction styles can be also deduced from the leadership styles reflecting the leader’s manner to organize the group activities. The example is the Situational Leadership II theory, which can be applied not only for business spheres, but also for the educational domain. The theory is a modified version of the previous model of Situational Leadership created by Paul Hersey and Kenneth Blanchard. Situational Leadership II theory developed by Kenneth Blanchard, Drea Zigarmi and Robert Nelson uses two dimensions of behaviour – supportive and directing which both may be exhibited by a leader but to a different extent (high and low) (Blanchard et al., 1993).

In our research we will stick to the most widely known theory of leadership styles developed by Lewin et al. (1939). The researchers studied how the leadership methods modified the interaction of the children club members. Lewin and his associates (1939) identified three leadership styles based on the degree of the leader’s involvement in the club activities. Although the theory was proposed in the last century, the styles it differentiates - authoritarian, democratic and laissez-faire ones - are still relevant for pedagogy.

We consider the approach of Lewin and his co-authors (1939) to be suitable for description of pedagogical interaction not only in brick and mortar classroom but in electronic environment as well. But as the description of the leadership styles shows, Lewin and his co-authors give a rather general outline of the leader’s modes of behaviour. So, it is reasonable to lay out the specifics of teacher-student interaction styles in the electronic environment.

To classify leadership styles Lewin’s theory takes into account the degree of control on behalf of the teacher and the degree of academic freedom on behalf of students. The dimension of control vs freedom gives a general understanding of the teacher’s mode of behaviour but does not specify education realms in application to online instruction.

To describe teacher-student interaction styles in the electronic environment we propose the following four realms of online EFL instruction, which can be used as criteria for detailed description of the styles.

The way the teacher determines the components of online learning process, such as the learning content, tasks, their quantity, the way of their implementation and deadlines.

The teacher’s readiness to organize online group activities.

The pattern the teacher gives the online feedback to the students.

The manner the teacher makes online assessment of the students’ assignments.

Using these criteria, we specified the characteristics of the authoritarian, democratic and laissez-faire teacher-student interaction styles in the electronic environment. The description of the styles on the four criteria is shown in Table

The specified characteristics of the authoritarian, democratic and laissez-faire teacher-student interaction styles in the electronic environment make it possible to find out students’ preferences related to online teacher-student interaction style using a questionnaire as an instrument of our research.

Thus, to examine students’ preferences related to online teacher-student interaction style we designed a questionnaire consisting of 12 multiple-choice questions. The questions covered all the four criteria of teacher-student interaction styles. The three alternative answers given to each of the questions were created so as to group students’ preferences into three categories. One of the alternatives was relevant to Authoritarian leadership style, another to Democratic one and the third to Laissez-faire leadership style (Table

Findings

Using the questionnaire, a survey was conducted among 95 first-year students (boys and girls) seeking a bachelor’s degree at National Research University of Electronic Technology (MIET), Moscow, Zelenograd, Russian Federation. The purpose of the survey was to define students’ preferences related to online teacher-student interaction styles. To score the results of the survey, one point was given for each answer, then all the points for each of the alternatives were summed up individually and the students were assigned to the category with the highest total: Democratic (D), Authoritarian (A) or Laissez-faire (L). If the results in two of the categories were equal or differed by one point, the students were assigned to both of the chosen categories (DA, DL, etc.). If the number of the points was equal in all the three categories, the students were assigned to all the three categories and marked as DAL. Table

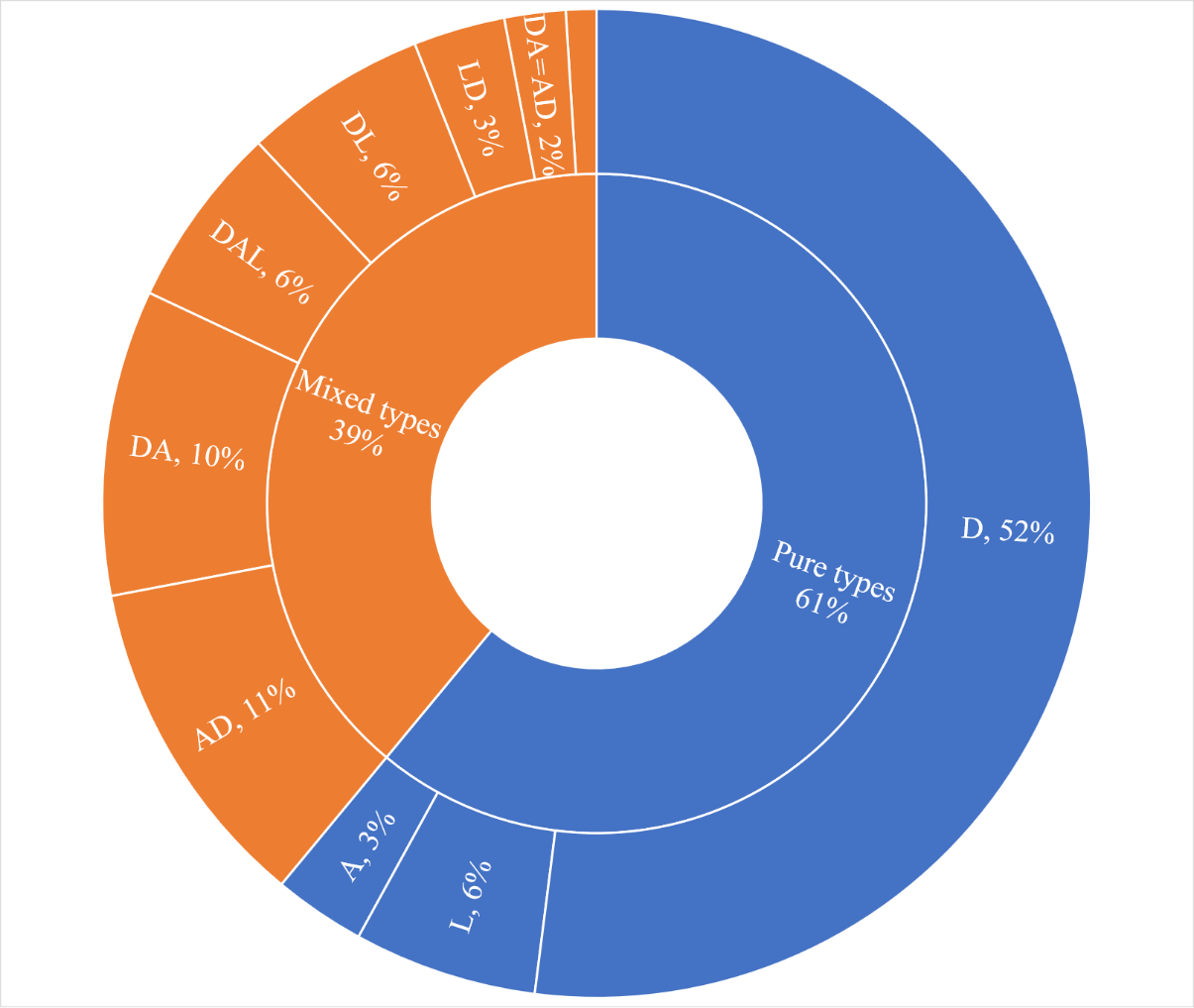

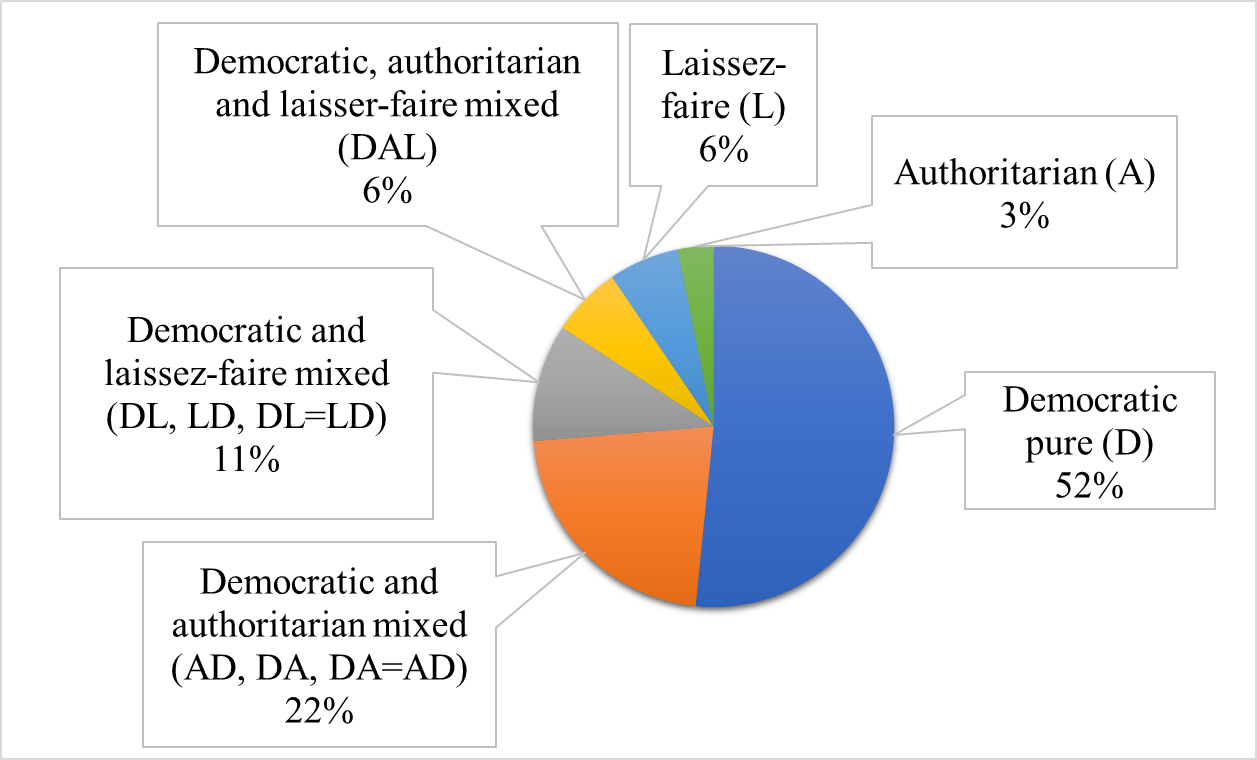

As one can see, the survey made it possible to obtain data showing students’ preferences related to online teacher-student interaction style. It turned out that apart from the so-called “pure” interaction styles preferences (marked by letters D, A, L in Table

If we group mixed interaction styles and count the total in them, we get 22 %of students who give preference to AD, DA or equally to DA and AD styles. Much smaller percentage of students – 11 % -prefer mixed DL and LD interaction styles. The aggregate results of students’ preferences related to online teacher-student interaction style are shown in Figure

Conclusion

Teacher-student interaction styles in the electronic environment can be deduced from the three interaction styles applied to face-to-face communication between the teacher and the students, notably authoritarian, democratic and laissez-faire styles. The characteristics of the corresponding teacher-student online interaction styles were given on the basis of the four criteria:

determining the components of online learning process

organizing online group activities

giving the online feedback

making online assessment.

The survey conducted among the students of National Research University of Electronic Technology (MIET) showed that half of the students (52%) prefer merely democratic EFL teacher to communicate with online. The second largest group of students (22%) choose the teacher who uses both democratic and authoritarian style for communicating during different online tasks. The teacher who uses both democratic and laissez-faire styles is chosen by 11% of the students. The other styles are less preferable, with the authoritarian one gaining the smallest percentage (3%).

The results of the study clearly demonstrate the desire of modern students to participate actively in the education process organized in the electronic environment. They would like to have a certain degree of freedom to decide upon the learning content, tasks, their quantity, the way of their implementation and deadlines. The students prefer to choose their online partners themselves to do tasks with. They dislike their assignments to be always assessed by a mark. At the same time online feedback from the teacher is rather important to them.

The research clearly shows that the students do not approve of authoritarian, monological or the so called “subject-object” style of communication. They do not want to be knowledge consumers any longer and are looking forward to an effective partnership/dialogue with the teacher. To take into consideration their point of view and, therefore, to make the process of online EFL learning more effective, we recommend that the teachers stop being abstract carriers of authoritative knowledge. Turning into equal interlocutors and seeing students as knowledge co-creators, as fellow travelers on the path of knowledge building and finding collaborative solutions seems to be the only way to mold our university graduates into innovative personnel.

References

- Blanchard, K. H., Zigarmi, D., & Nelson, R. B. (1993). Situational leadership® After 25 years: A retrospective. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 1(1), 22-36.

- Cinque, M. (2016). “Lost in translation”. Soft skills development in European countries. Tuning Journal for Higher education, 3(2), 389-427. https://doi.org/10.18543/tjhe-3(2)-2016pp389-427

- Clemente, J. (2018). Interpersonal Justice in the Classroom: The Role of Respectful Treatment and Nature of Teacher-Student Relationships on Teacher and Student Outcomes. Philippine Sociological Review, 66, 61-90. https://doi.org/10.2307/26905844

- Dever, B. V., & Karabenick, S. A. (2011). Is Authoritative Teaching Beneficial for All Students? A Multi-Level Model of the Effects of Teaching Style on Interest and Achievement. School Psychology Quarterly, 26 (2), 131-144. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022985.

- Dinham, S. (2007). Authoritative leadership, action learning and student accomplishment. http://research.acer.edu.au/research_conference_2007/3

- Estepp, C., & Roberts, T. (2015). Teacher immediacy and professor/student rapport as predictors of motivation and engagement. NACTA Journal, 59(2), 155-163.

- Evdokimova, M. (2020). Homo Innovative as an educational ideal in the context of training teachers at non-linguistic Universities. Proceedings of INTED2020 Conference 2nd-4th March 2020, Valencia, Spain, 0120-0124.

- Evdokimova, M., Baydikova, N., & Davidenko, Y. (2018). Grouping Criteria for Training Foreign Language Interpersonal Communication Skills of Engineering Students. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences, 35, 264-272. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.02.30

- Erdel, D., & Takkac, M. (2019). The Relationship between Teacher Classroom Leadership and Learner Autonomy: The Case of EFL Classrooms. International Journal of Education, 8(3), 752-770.

- Fadel, C. (2015). Redesigning the Curriculum for a 21st Century Education the CCR Foundational White Paper. https://curriculumredesign.org/wp-content/uploads/CCR-FoundationalPaper_FINAL.pdf

- Grasha, A. F. (1996). Teaching with Style: A Practical Guide to Enhancing Learning by Understanding Teaching and Learning Styles. Alliance Publishers.

- Jones, L. (2007). The Student-Centered Classroom. Cambridge University Press.

- Klaus, P. (2010). Communication Breakdown. California Job Journal, 28, 1-9.

- Leithwood, K., Louis, K. S., Wahlstrom, K., Anderson, S., Mascall, B., & Gordon, M. (2010). How Successful Leadership Influences Student Learning: The Second Installment of a Longer Story. In A. Hargreaves et al. (eds.), Second International Handbook of Educational Change (pp. 611 – 629). Springer International Handbooks of Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2660-6_35.

- Levy, M., & Moore, P. J. (2018). Qualitative research in CALL. Language Learning & Technology, 22(2), 1-7. https://doi.org/10125/44638

- Lewin, K., Lippitt, R., & White, R.K. (1939). Patterns of aggressive behavior in experimentally created social climates. Journal of Social Psychology, 10, 271-301.

- Moore, P. J., Mynard, J., Wongsarnpigoon, I., & Yamamoto, K. (2019). Autonomy and interdependence in a self-directed learning course. Relay Journal, 2(1), 218-227.

- OECD. (2018). The Future of Education and Skills. Education 2030. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030/E2030%20Position%20Paper%20(05.04.2018).pdf

- Robinson, V. (2017). Capabilities required for leading improvement: Challenges for researchers and developers. 2009 - 2019 ACER Research Conferences. https://research.acer.edu.au/research_conference/RC2017/28august/2

- Rogers, С. (1983). Freedom to learn for the 80's. Ch. E. Merrill Publ. Company, A Bell & Howell Company.

- Siemens, G., Gašević, D., & Dawson, S. (2015). Preparing for the Digital University: a review of the history and current state of distance, blended, and online learning. Athabasca University. http://linkresearchlab.org/PreparingDigitalUniversity.pdf

- Stroet, K., Opdenakker, M. C., & Minnaert, A. (2013). Effects of need supportive teaching on early adolescents’ motivation and engagement: A review of the literature. Educational Research Review, 9, 65-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2012.11.003

- Yang, M. K., & Shadiev, R. (2019). Review of Research on Technologies for Language Learning and Teaching. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 7, 171-181. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2019.73014

- Yao, Z., & Luh, W. (2019). A New Longitudinal Examination on the Relationship between Teaching Style and Adolescent Depression. International Journal of Psychology and Educational Studies, 6(1), 1‐9. https://doi.org/10.17220/ijpes.2019.01.001

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

20 November 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-094-5

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

95

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1241

Subjects

Sociolinguistics, discourse analysis, bilingualism, multilingualism

Cite this article as:

Evdokimova, M. G., Davidenko, E. S., & Baydikova, N. L. (2020). Teacher-Student Interaction Styles In The Electronic Environment Of Foreign Language Instruction. In Е. Tareva, & T. N. Bokova (Eds.), Dialogue of Cultures - Culture of Dialogue: from Conflicting to Understanding, vol 95. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 271-281). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.11.03.29