Abstract

This paper presents the results of studies aimed at comparing the role of temporal and social comparisons in assessing one’s own subjective emotional age (how old do I look) and the subjective emotional age of other people from photographs. Temporal assessments are based on one’s mental ideas about their age identity, while social comparisons suggest implicit ideas about the ages in a given population, including stereotypes, attitudes, ideals. Subjective emotional age is an anchor representation since it is based on one’s feedback about one’s health and appearance. The study participants were 145 mentally healthy people aged 20-70 years. The analysis was conducted by age groups: 20-30; 40-50 60-70 years old. We used the Barak Subjective Age Questionnaire (2009) and 30 recent photographs of people of different ages (10 photos for each age group of 20-30, 40-50, and 60-70 year-olds).The results showed that the assessment of the subjective emotional age is much more accurate from photographs of people. The photographs of young people were estimated to be slightly older than their real age, and photographs of older people were estimated to be younger than their real age. Despite the differences in estimates of one’s own subjective emotional age and the age of people in photographs, there is a general tendency to evaluate older people as being younger than they are. Temporal comparisons are the actualization of one’s mental notions. However, social comparisons and accounting for social age markers also play an important role.

Keywords: Adultagingemotional subjective agesocial comparisonsubjective agetemporal comparison

Introduction

The nature of age differences is a fundamental question in the study of human behavior. Although chronological age is a fundamental dimension, for understanding human development and its internal subjective coordinates, subjective age seems to be a key construct that allows us to discover new ways of analyzing self-determination, subjective choice of own life scenarios and their interpretation. Two levels of mental representations may determine individual age-related identification (subjective age): stable (anchor) and more labile, changing proximal age references. Stable representations are individual development models that mark one's behavior with respect to age-related mental patterns. Proximal representations or mental age markers change according to events that problematize age.

Recently, the number of studies of subjective age and their scope allows us to assess the phenomenon of subjective age as a predictor of successful/dysfunctional aging, the ability to cope with traumatic situations, a predictor of dementia, death in the older and other people (Hofman et al., 2016; Hubly & Arim, 2012; Stephan & Satin, 2015; Stephan et al., 2018; Shrira et al., 2014; Palgi, 2016). Wherein older than the chronological age of the respondents becomes a predictor of a dysfunctional course of life.

These studies, conducted with large samples of respondents, are limited only to an analysis of subjective biological age (how old a person feels), while other no less significant components of subjective age (emotional – how old do I look; social – what age do I act; intellectual – what age do my interests correspond to) remain outside the scope of the analysis. At the same time, as our studies have shown, all the components of subjective age play an important role in the processes of life activity and regulation of behavior, and their role changes in different periods of adulthood and aging (Sergienko & Kireeva, 2015).

Reevaluation of one’s age is stronger in those areas where it is not easy to get information or feedback unequivocally. Biological aspects of subjective age, such as health and attractiveness, give more definite feedback, their standards are less ambiguous than the general perception of age or age activity and interests. Thus, in our studies, the minimal difference in chronological and subjective age was found precisely in the emotional assessment of one’s appearance. Indeed, health and attractiveness were highly reliable predictors of age-related identification.

Another informational aspect relates to those prototypes against which people evaluate themselves. So, if people are guided by outdated prototypes (for example, those of the previous generation) to evaluate their subjective age, then they can underestimate the age of other people as well. This aspect has not been studied experimentally, and it is related to the question of the influence of age-related stereotypes, their implicit models, and dynamics in human development. In our work with Yu. D. Kireeva (as cited in Sergienko & Kireeva, 2015) we compared the chronological age of a person in photographs and their subjective assessment by respondents (how do they look, which corresponds to emotional subjective age). The study involved 86 people. The age estimated from 10 photographs for each age group was much more realistic and was close to the chronological age of the models. These data indicate that people are more oriented towards real ideas about themselves and temporal comparisons of their ideas (about their physical condition and attractiveness) rather than towards stereotypes and ideals broadcast by society (the value of youth at all costs, ever-young looking actresses, media personas, etc.). In this case, the assumption of the higher reliability of feedback about the physical condition and attractiveness of a person for implicit cognitive models of age and its identification is more confirmed than socially determined comparisons as the basis of age identity (Sergienko, 2014).

Problem Statement

Subjective age was assessed by a questionnaire (Barak, 2009).

To assess the subjective emotional age of other people, respondents were offered 30 photographs of 10 photographs of people 20-30, 40-50 and 60-70 years old, contemporaries actually living in the same region. They were asked: How old is the person in this photo?

Research Questions

-

Compare one’s own subjective emotional age (how old do I look) with the age evaluation of people of different ages in photographs.

-

Assess the contribution of temporal and social comparisons to estimates of subjective emotional age.

Purpose of the Study

The question of the psychological mechanisms of the phenomenon of subjective age remains poorly studied. In the previous study, only 10 photos of examples of people of different ages were presented, which limited the possibilities for interpretation. The purpose of this work is to compare the subjective emotional age of people of 20 to 70 years of age and their assessment of the subjective emotional age of photos of examples of 20-70 year-olds.

Research Methods

The study participants were 145 mentally healthy people living in Moscow and the Moscow Region aged 20-70 years (38 men (27%) and 103 women (73%). The analysis was carried out by age groups: 20-30 year-olds - 51 people (14 men and 37 women); 40-50 year-olds - 47 people (9 men and 38 women); 60-70 year-olds - 47 people (16 men and 31 women). Subjective age was assessed by a questionnaire (Barak, 2009). To assess the subjective emotional age of other people, respondents were offered 30 photographs of 10 photographs of people 20-30, 40-50 and 60-70 years old, contemporaries actually living in the same region. They were asked: How old is the person in this photo?

Findings

Table

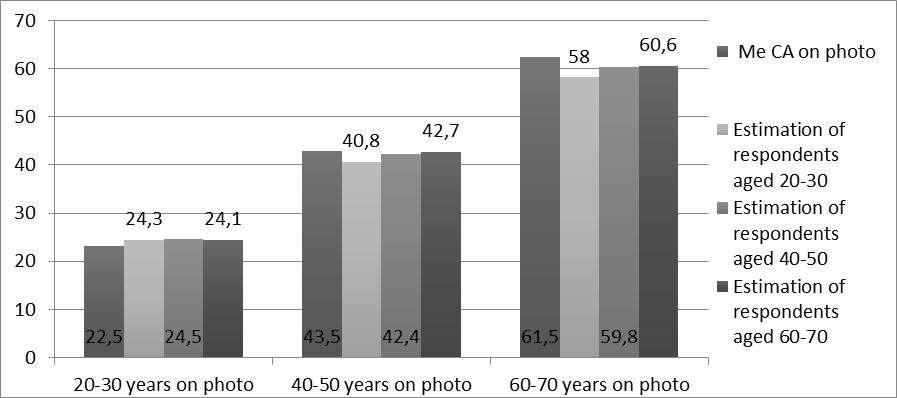

From Figure

Respondents gave the most accurate estimates regarding their own age group. Even though the difference in subjective estimates of how old a person looks and the estimates of the actual subjective emotional age were significantly different, for all ages there was a tendency to evaluate people of 20-30 years old as older and people of 40-50 and, especially, of 60-70 years old as younger. Such dynamics reflect a general phenomenon, where the change in age estimates towards their subjective decrease in age begins at 23–25 years of age (Galambos, 2009).

According to the data obtained, young people are the least accurate in assessing the emotional age of other people of different age groups. Since young people, when evaluating their peers, adults and older people, rather endow these assessments with implicit social ideas about age and its external markers, it should be assumed that temporal comparisons of their emotional age, based on comparisons of themselves in time (temporal) and social comparisons of generations of adults and seniors are very different and more accurate. This indicates that people of all ages mainly rely on temporal comparisons when evaluating other people. However, when evaluating people of older age than themselves, they have difficulties due to the lack of their own mental coordinates. Therefore, social comparisons come to the fore in this case.

The data in Table

Conclusion

Estimates of age from photographs are significantly closer to real age than subjective age-related identification.

Photos of young people are estimated to be somewhat older than their real age, and middle-aged and older people are estimated to be younger. Despite the differences in the estimates of one’s own subjective emotional age and the age of people in the photographs, there is a general tendency to evaluate older people to be younger than they are.

As shown by comparisons of the subjective emotional age of oneself and people in photographs, temporal comparisons (when assessing oneself) are combined with social notions, including implicit conceptions about age markers.

Temporal comparisons are the actualization of one's mental notions. However, social comparisons and the accounting for social age markers also play an important role, as evidenced by data on the relationship of subjective age with important life events, the social status of a worker or a pensioner, the presence of a family, children, grandchildren, and the educational level (Sergienko & Kireeva, 2015; Sergienko & Melekhin, 2016).

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by RFBR foundation, grant N. 17-29-02155.

References

- Melekhin A.I., & Sergienko E.A. (2015). Sub"ektivnyy vozrast kak prediktor zhiznedeyatel'nosti v pozdnikh vozrastakh. Sovremennaya zarubezhnaya psikhologiya. [Subjective age as a predictor of life in later ages]. Sovremennaya zarubezhnaya psikhologiya, 4, 6-14.

- Sergienko E.A., & Kireeva Yu. D. (2015). Individual'nye varianty sub"ektivnogo vozrasta i ikh vzaimosvyazi s faktorami vremennoy perspektivy i kachestvom zhizni. Psikholog. [Individual options for subjective age and their relationship with factors of time perspective and quality of life] Psychologist. Journal, 36(4), 39-51.

- Barak, B. (2009). Age identity: A cross-cultural global approach. International journal of behavioral development, 33(1), 2-11.

- Bergland, A., Nicolaisen, M., & Thorsen, K. (2014). Predictors of subjective age in people aged 40–79 years: A five-year follow-up study. The impact of mastery, mental and physical health. Aging & Mental Health, 18(5), 653-661.

- Braman, A. C. (2003). What is subjective age and how does one determine it: The role of social and temporal comparisons. (Doctoral Dissertation). Washington University.

- Galambos, N. L., Turner, P. K., & Tilton-Weaver, L. C. (2005). Chronological and subjective age in emerging adulthood: The crossover effect. Journal of adolescent research, 20(5), 538-556.

- Galambos, N. L., Albrecht, A. K., & Jansson, S. M. (2009). Dating, sex, and substance use predict increases in adolescents' subjective age across two years. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 33(1), 32-41.

- Mejía, S. T., Ryan, L. H., Gonzalez, R., & Smith, J. (2017). Successful aging as the intersection of individual resources, age, environment, and experiences of well-being in daily activities. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(2), 279-289.

- Rippon, I., & Steptoe, A. (2018). Is the relationship between subjective age, depressive symptoms and activities of daily living bidirectional?. Social Science & Medicine, 214, 41-48.

- Stephan, Y., Sutin, A. R., & Terracciano, A. (2018). Subjective Age and Mortality in Three Longitudinal Samples. Psychosomatic medicine, 80(7), 659-664.

- Stephan, Y., Sutin, A. R., Luchetti, M., & Terracciano, A. (2018). Subjective age and risk of incident dementia: Evidence from the National Health and Aging Trends survey. Journal of psychiatric research, 100, 1-4.

- Xiao, L., Yang, H., Du, W., Lei, H., Wang, Z., & Shao, J. (2019). Subjective age and depressive symptoms among Chinese older adults: A moderated mediation model of perceived control and self-perceptions of aging. Psychiatry research, 271, 114-120.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

15 November 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-093-8

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

94

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-890

Subjects

Psychology, personality, virtual, personality psychology, identity, virtual identity, digital space

Cite this article as:

Sergienko, E. (2020). Psychological Mechanisms Of Subjective Age. In T. Martsinkovskaya, & V. Orestova (Eds.), Psychology of Personality: Real and Virtual Context, vol 94. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 715-720). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.11.02.87