Abstract

Globalization and technological advancements in the 21st century have drastically transformed the workplace practices. To ensure that graduates are standout contenders in today’s competitive job market, universities are in need to offer a global work-based learning opportunity to the students at the campus. A lack of studies is visible regarding the exploration of key influencing factors in enhancing graduates’ employability particularly in the context of Malaysia. A literature review is conducted on the topic of employability exhibited the yearly distribution, methodologies, and dimensions of employability of graduates. In order to understand the role of internationalization at home (IaH), intercultural competence and global citizenship in fostering graduates’ employability, a conceptual framework is suggested. The framework is oriented in concepts of internationalization at home (IaH), intercultural competence, and global citizenship as key constructs in enhancing the employability of Malaysian graduates. The proposed model offered institutional support as a moderator which is presumed to have a significant effect on the defined relationships. The directions for future research are given at the end.

Keywords: Internationalization at homeintercultural competenceglobal citizenshipgraduates’ employability

Introduction

A major and substantially common challenge in the 21st century is the deficit of global graduate skills. A recent survey conducted by QS named QS employer survey 2018 and QS Applicant Survey 2018 highlighted a lack of skills across the board and also a lack of expectations between students and employers (Abas & Imam, 2016; Omar et al., 2012; Poon, 2012). Such findings may indicate that there is a lack of internationalization and global competencies among students, and At the institutional level, a contact obstacle must be overcome between universities and industry to close the skill gap (Arrowsmith et al., 2011; Anho, 2011; Di Pietro, 2019; Holmes, 2013; Ornellas et al., 2019; Teichler, 2011). The findings of these surveys suggest that potential graduates do not fully adequate with how companies value soft and employability skills (Ismail et al., 2011; Saleh, 2019; Schomburg, 2011). Students have a habit of to overvalue the standing of leadership and creativity skills, rather undervalue the significance of global mindfulness, flexibility/adaptability, and intercultural skills, that are highly considered by employers (Chan, 2011; Hinchliffe & Jolly, 2011; Tomlinson, 2012; Xiao-qian, 2011). Such differences clearly require awareness-raising so that students are mindful of the skills organizations prioritizing them before they graduate (Shumilova et al., 2012; Wang & Tsai, 2014). It may also be reflective of a failure to properly train students in areas of productive jobs (Farčnik & Domadenik, 2012; Ornellas et al., 2019; Wilton, 2011).

From international, intercultural and global perspective, Van Gaalen and Gielesen (2014) assert that to achieve the graduates with intercultural, international and global skill only “if institutions consciously create controlled situations that lead to intercultural collaboration and the utilization of students’ specific international knowledge” (p. 16). This argument emphasized the need for an environment internationally and interculturally integrated for the students' development of global learning (Di Pietro, 2019; Pinto & Ramalheira, 2017; Puhakka et al., 2010; Støren & Aamodt, 2010). Di Pietro (2019) described the high potential for providing professional and individual skills to graduates but is still not widely practiced even in international organizations. In the same vein, Jones (2013) argued that domestic environments could play an equal role in offering opportunities for experience international learning in an intercultural context through campus-based internationalization and intercultural learning. These practices would be helpful in increasing the employability rate of local students (Asonitou, 2015; Huang, 2013; Jones, 2013). At the institutional level, some authors argued that internationalization at home (IaH), intercultural competence (Ciriaci & Muscio, 2014) and global citizenship are the factors that contribute to the development of students' employability (Al-Mutairi et al., 2014; Ayoubi et al., 2017; Yoong et al., 2017). For instance, this has started in the U.S. with some early studies conducted by Soria and Troisi (2014) where they emphasized that IaH and intercultural competence programs may yield greater benefits than study abroad in terms of acquiring global, international, and intercultural competencies which greater the chances of graduates’ employability (Barker & Mak, 2013; González-Romá et al., 2018; Støren & Aamodt, 2010).

Problem Statement

The employability of graduates in Malaysia is not a concern that is new and none-existed before (Belwal et al., 2017; Coetzee, 2017). It was among discussions from a decade ago. There is an increasing number of competition among the graduates because of a limited number of availability of jobs (Pouratashi & Zamani, 2019; Shafie & Nayan, 2010). University students have been reported to lack several skills, particularly problem-solving, communication and other soft skills (Bello et al., 2013; Hanapi & Nordin, 2014; Harvey & Shahjahan, 2013). On the other hand, hard skills that are also lacking among students include lack of technical expertise, lack of knowledge and communication skills in English. The lack of skills is also identified as other causes of unemployment for Malaysian graduates, according to which about 30,000 students were employed in an area not matching their higher education qualifications (Coetzee et al., 2015; Hanapi & Nordin, 2014). Investigating the youth unemployment further to examine graduates in particular (Cai, 2013; de Guzman & Choi, 2013), a recent report in 2015 showed that only 53% of the graduates earned jobs within six months of graduation, 24% of graduates remains unemployed, and 18% were in tertiary studies in Malaysia (Shanmugam, 2017). The only reasons given for 53 percent securing jobs were the gap between university training and employers' demanding skills. The majority of university programs do not reflect current qualifications (Shanmugam, 2017). The given statistics, therefore, indicating the need for academics reforms in Malaysian higher education institutions to meet the challenges of globally competent job markets.

The most noticeable skill which is lacking among Malaysian graduates is the resilience/dealing with conflict and adaptability at a diverse workplace (Nisha & Rajasekaran, 2018; Shafie & Nayan, 2010; Wickramasinghe & Perera, 2010). Researchers suggested that these are not personality-related traits but behavioral characteristics that are learnable, thus higher education institutions (HEIs) enable themselves to advance the tools to cultivate these behaviors among students (Clarke, 2018; Tran, 2015). Considering that the same problems are repeated for Malaysian workers, it seems fitting, in order to effectively resolve the foreign violence, that employers must share experiences and solutions with enhanced cooperation with academic institutions (Fenta et al., 2019; Wang & Tsai, 2014). Global graduates necessitate and must be able to apply skills and the appropriate qualities covering global thinking and cultural endurance (Di Pietro, 2015; Eurico et al., 2015).

Throughout academic literature, a great deal is debated about how colleges and universities develop students for jobs, sometimes named as the "graduate ability gap" (Andrews & Russell, 2012; Chan, 2011; Fatima & Ameen 2011). However, despite the discussion, There seems still to be an inadequate best possible way to prepare graduates with the hard skills needed for work and still less consideration of how best to equip students with the soft abilities needed for a constantly changing and troubling labor market. This, therefore, stress the need for increased graduates’ employability through offering students’ international, intercultural and global competencies to overcome the challenges of unemployment and mismatch of skills. It is crucial to enable Malaysian students to participate in global curriculum and intercultural relations between students. Cross-cultural skills (Hinchliffe & Jolly, 2011) clearly mean employers and the attractiveness of the sector in international student recruitment is improving (Angelova & Zhao, 2016; Messum et al., 2015; Nilsson, 2010). Hasan et al. (2016) support this claim by their research emphasizing that the inconsistencies of employer and qualifications is one of the main causes of unemployment in Malaysia. Dr. Soji, CEO of a management consultant company's mentioned the need of graduate skills as he said that the problem is not unemployment, but the absence of employability by the graduates (Jackson & Chapman, 2012; Suleman, 2016; Tomlinson, 2010).

Malaysian graduates often have lack communication skills and cross-cultural knowledge, which reduces their chances of participating in the increasingly global labor market (Harvey & Shahjahan, 2013; Stiwne & Alves, 2010). According to QS Graduate Employability Ranking 2019, there is not a single university in Malaysia that makes a place in the top 100 universities (Sarkar et al., 2016). Universiti Malaya (UM) is the only university that establishes its position in the top 200. As shown in a World Bank and Talent Corp study, only less than 10 percent of companies have developed university curricula or programs. The study also discussed the global youth unemployment issue, which in Malaysia is 13.2 percent. Of people aged 15-19, the highest unemployment rate is 18.7%, followed by those aged 20-24, 11.9%. While, 68 percent consider the skills of communication to be the most significant factor among employees, followed by work experience, interpersonal abilities, passion, and engagement (Beelen & De Wit, 2012; Finch et al., 2016; Saad & Majid, 2014; Stiwne & Alves, 2010).

Given the above statements, there is a need to inline the strategic objectives of an educational institution with the industrial transformation, that promotes both the development and implementation of a curriculum of a global perspective which results in improved employability for its students. A dynamic framework, incorporating the key influencing factors being considered as the determinants of the graduates’ employability will be highly assistive in this regard. With a strong emphasis on building international, intercultural and global skills, a university can produce globally employable graduates and contribute to the national economic growth by reducing the unemployment rate.

Research Questions

The study aims to answer the following questions;

What are the distribution, methodologies, and dimensions of literature on the employability of graduates?

How a framework is needed and can be supportive to enhance the employability of graduates?

Purpose of the Study

This study, hence, set out to develops a research framework by considering the key influencing factors such as internationalization at home, intercultural competence, and global citizenship for the developing graduates’ employability among Malaysian graduates. The study suggests how students can contribute to the global job market by having the desired employability skills for the 21st century.

The central feature of this study is to highlight the need to encourage universities to produce internationally, interculturally, and globally competent Malaysian graduates who are capable to meet the job requirements of the global market (Finch et al., 2013; Pouratashi & Zamani, 2019). This study also stresses the need for improved collaboration and networking between local and international industry and Malaysian higher education institutions. Schech et al. (2017) called for further studies in order to examine the relation between the factors of internationalization and globalization and employability, because the links of those variables in the Malaysian universities are not very well known. Some authors emphasized the need for a literature review on the issues of employability to bring clarity in this specific research area (Andrews & Russell, 2012; Succi, 2019; Suleman, 2018). Given this, the main aims of this study are to conduct a literature review of the previous study on employability and offer a conceptual framework which would be supportive in explaining the relationships between internationalization at home, intercultural competence, global citizenship, and graduates’ employability among Malaysian students, as well as to explore the mediating influence of institutional support on these relationships (Lau et al., 2014; Pheko & Molefhe, 2017; Sin et al., 2016).

Research Methods

A literature review, as defined by Fink (1998) is a systematic, clear and reproductive method to classify the current documented text set, analyze it and interpret it. The analysis of documents aims at opening up material that is not to be created by the researcher on the basis of the data collection. Literature reviews are usually directed at two objectives: firstly, by defining trends, themes and problems (Pavlin & Svetlik, 2014) to summarize the current research. Secondly, this could assist in identifying the field's conceptual material and can help to develop a conceptual model or framework.

The literature reviews might also be understood as a content analysis from a methodical point of view where quantitative and qualitative factors are combined in order to evaluate (descriptive) structural and content requirements. In the content, analysis, the analyst decides different ways of understanding and extending a particular research topic. This study employed content analysis through a descriptive method to direct and interpret the literature review on graduates’ employability.

Delimitations and Literature Search

To conduct a literature review, identifying clear boundaries to delimit the research scope is of high importance. Three key points are made in this context:

This research was only directed at articles in scientific journals that have been reviewed in English. This does not include articles in languages other than English.

Publications with the core focus on higher education institutions are considered. This debate includes the graduates’ employability through the integration of internationalization of higher education, intercultural competence, and global citizenship.

Articles that lie in the timeframe of 2010 to 2019 are considered for review.

A standardized keyword search was conducted which have an aim to look for related publications. Large databases, such as those operated by major publishers, were used to search for relevant articles. Among those, Springer (www.springerlink.com), Wiley (www.wiley.com), Elsevier (www.sciencedirect.com), Emerald (www.emeraldinsight.com), Scopus (www.scopus.com), and Ebsco (www.ebsco.com) were the targeted portals for article search.

Findings

Content Analysis

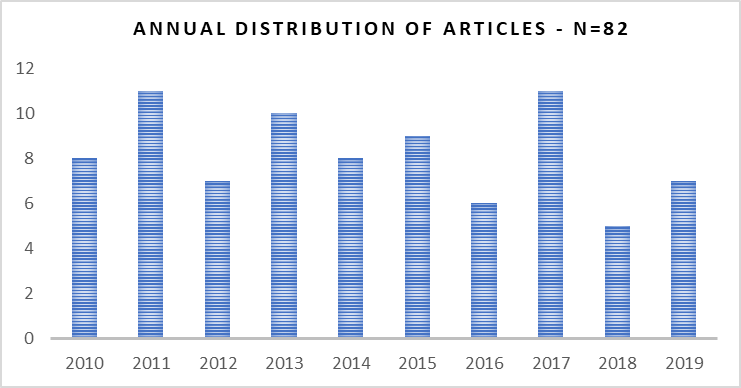

A total of 82 documents have been listed based on the mentioned delimitations. Concise measurements were used to identify the documents in the first phase of the evaluation. A concise analysis has further analyzed the content of the articles. This includes (a) How are publications distributed over the period?? (2) Which methodologies are used for research? (3) What employability dimensions or determinants are discussed?

Descriptive Analysis

There are 82 papers were identified in the basic literature search. Figure

Research Methodologies Applied

There have been identified five methodologies of research: (1) conceptual and theoretical papers; (2) literature reviews; (3) surveys; (4) empirical/modeling papers; and (5) case studies. Table

Determinants of Employability

Based on the thorough reviews, three broader categories were formed such as internationalization at home (IaH), intercultural competence, and global citizenship. These three categories along with their further dimensions and constructs were found highly influential for enhancing graduates’ employability. Table

Graduates’ Employability and its Importance in Today’s Workforce

Many authors have indicated that employers are more intended to recruit applicants who have better soft skills instead of characteristics of hardworking (Lambert & Usher, 2013; Nilsson & Ripmeester, 2016; Watkins & Smith, 2018). Employers claim they can engender and strengthen employee know-how and strategies, but creation and training of soft skills are very difficult (Rao, 2015; Vázquez-Ingelmo et al., 2018; Watkins & Smith, 2018). Therefore, they tend to employ workers with a broad range of skills instead of technical abilities (Peterson, 2016; Zegwaard & McCurdy, 2014). Employers contend that “recruit for attitude and train for skill” (Rao, 2015, p.45). Sutton (2002) noted that companies considered soft skills at the top to differentiate the candidates in the recruitment process (Robles, 2012).

As noted by Yang et al. (2015) and Seth and Seth (2013), employability skills are more likely to lead to increasing the chances of an individual's employability (Sumanasiri et al., 2015; Su & Zhang, 2015). The value of employability can be associated with the way companies function in modern times (Helyer & Lee, 2014). In order to design jobs today, individuals are in need to interact and work with teams to accomplish their organizational objectives (Matsouka & Mihail, 2016; Poon, 2014).

Increased mobility is being observed, as individuals not only move to work in various geographical areas within the organization but try and find advanced and challenging roles for the sake of improvement in their careers (Fenta et al., 2019; Puhakka, et al., 2010; Yizhong et al., 2017). This renders it essential that we understand and use multiple languages, explore different cultures and work with diverse workgroups (Fletcher et al., 2017; Ramadi et al., 2015). Technological changes continue to require workers to learn recent software and mechanisms and strive for a lifelong learning stance (Greenwood et al., 2015; Osmani et al., 2019; Schech et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2015). The acquisition, practice, and use of employees ' skills (such as teamwork abilities, creative and problem-solving and critical-thinking) have therefore become essential for survival and workplace success.

Internationalization at Home and Graduates’ Employability

Internationalization at Home (IaH) refers to an approach to higher education internationalization that extends beyond the movements of a minority of students and instead emphasized the importance of providing students with an international curriculum and the inclusion of intercultural communication in a different cultural environment (Wächter, 2003). This is a wide term, however, which calls for a clear and important contextualization and has been applied in regional forms throughout the UK, Northern Europe, Australia, Canada, and the US. IaH is defined by Nilsson (2003) as “any internationally related activity with the exception of outbound student mobility” (p. 31).

Incorporating global awareness into an Internationalized program was the first priority of IaH. But Killick (2014) found that application as part of an "extended curriculum" could also be used in “practice, including voluntary and global citizenship awards” (p. 36), While Knight (2008) pointed out that "at home" concept gives greater prominence to outsourcing activities, linkages and the integration of foreign students and scholars into the campus and the activities of local and ethnic cultures. Furthermore, the readiness of students for the worldwide workplace will be one of the 10 drivers of internalization as proposed by Green (2012).

Knight (2008) states that to achieve these goals the “Involvement of students in local cultural and ethnic organizations through internships, placements and applied research” (p. 14). A connection between job creation and internationalization appears to be clear: Beelen & De Wit (2012) established that improved "preparation" of students for a globalized world is the main reason for internationalization among universities. On the other hand, almost 90% considered international skills, including being able to work in an unfriendly environment or culture, in Lambert and Usher (2013) survey of 1400 local Canadian students. Moreover, the British Council (2013) and Think Global (2011) published studies into the relevance of cross-cultural skills to employers and the gap among the needs of employers to recruit internationally and globally prepared graduates (Ali, 2019; Sutton, 2002; Van Gaalen & Gielesen, 2014). The Erasmus Impact Report (European Commission, 2014) reveals that 92% of industrial employers reviewed aimed to achieve' transverse competency,' including transparency and interest, confidence and empathy towards other beliefs. Killick (2017), in his recent study, highlighted the significance of' ‘cultural agility' to global graduates (p. 43) — the ability to be respectful to others 'culture without introducing one's own’ (Aulakh & Kotabe, 1997; Nilsson, 2003; Smith et al., 2019; Wellman, 2010).

Intercultural Competence and Graduates’ Employability

A number of previous research on the concept of intercultural competence along with the relevant abilities has been carried (Greenwood et al., 2015; O’Leary, 2017; Tomlinson, 2017). Some of these are described by Jones (2013), who emphasize the numerous words that seem to be synonymous to explain the broader concept of intercultural competence. Some of those terms are "cross-cultural capacity," "intercultural sensitivity," and "cultural fluency." In Freeman et al. (2009), intercultural competence is described as a process of dynamic, continuous, interactive, self-reflected learning that transforms culturally effective and appropriate communications and interactions. There is no clear understanding of a single culture which suggests that societies are running efficiently and our beliefs, perceptions, and prejudices are questioned. (Jones, 2013; Orence & Laguador, 2013). It can lead to a crucial role in higher education in creating students who are willing to solve the global issues in a range of culturally and environmentally sensitive locations (Aulakh & Kotabe, 1997; Ramadi et al., 2015; Sapaat et al., 2011).

Barker and Mak (2013) highlighted a crucial aspect of establishing intercultural skills with an aim to develop students with a motivation of learning to adjust to meetings beyond their comfort zones. This approach applies more to crossing possible barriers not only of nationality and culture, but also of race, sex, class, or other types of social and cultural norms (Khirotdin et al., 2019; Barker & Mak, 2013; Wächter, 2003). These ideas are increasingly resonated in all higher learning institutions, realizing that the intercultural skills necessary for operations effectively in global contexts are equally important to live and work in our ever more diverse local societies (Burke et al., 2017; Watkins & Smith, 2018).

Global Citizenship and Employability

In terms of the role of universities and other educational institutions as an integral proxy for the importance of university education globally, a growing focus has been put on allowing for employability and job creation (Burke et al., 2017; European Commission, 2014). In Australia, New Zealand, and the UK, several universities now have global citizenship education programs, aimed at improving the opportunities for graduates ' jobs (Bridgstock, 2009; British Council, 2013; Mtawa et al., 2019; Nilsson & Ripmeester, 2016; Tomlinson, 2017).

Holmes (2013) acknowledged the idea that universities can, and must, produce "ready-to-work graduates" is often based on the notion of global citizenship. Employability concepts are often perplexed with results for employment, i.e. job security following graduation or higher pay which however needs to think in terms of global terms such as global citizenship and its impact (Burke et al., 2017; Zegwaard & McCurdy, 2014). Many authors concluded that employment is, however, mainly conceived as the global skills and personal attributes which industry considers essential, and which graduates need to secure their jobs (Bridgstock, 2009; Freeman et al., 2009; Holmes, 2013; Jackson, 2016).

Role of Institutional Support in Enhancing Employability

In the recent global and international learning environment, a number of factors affecting students’ learning outcomes (Holmes, 2013; Jackson, 2016). Those factors include classroom atmosphere, institutional learning environment and/or development of curriculum (Killick, 2017). Positive administrative and institutional support (e.g. international programs, and interactions with peer learners, organizational scholastic support) can result in positive learning outcomes (Green, 2012; Peterson, 2016). According to Barefoot (2004), institutional support is a vital factor in learning persistence. He further claimed that the majority of the available research on learning outcomes focuses on learner’s personal behavior, attitude, characteristics or instructional perspectives rather than the institutional support or role.

Institutional support comprises a positive educational environment, colleagues’ support, supervisor’s support, and a positive institutional atmosphere for learning (Jones, 2013; Tymon, 2013; Jackling & Natoli, 2015). Positive educational environment refers to the situations and circumstances favorable for students’ intercultural, global and international learning. Supervisor support denotes to the supervisor’s emphasis on the value of academic training and positively integrate to the students’ learning outcomes (European Commission, 2014; Knight, 2008). In the same vein, colleague’s support” refers to the support provided by one’s colleagues in the process of learning and underpinning the application of such learning to the work situation (Humburg et al., 2013; Minten & Forsyth, 2014). Organizational atmosphere means features such as behavioral patterns, shared beliefs, living structures and cultural values which can impact the behaviors of individuals or a group (Seth & Seth, 2013). Hence, institutional support is the mutual effort of all stakeholders which induces positive learning outcomes at higher education institutes (Robles, 2012; Hunt et al., 2013).

Conceptual Framework

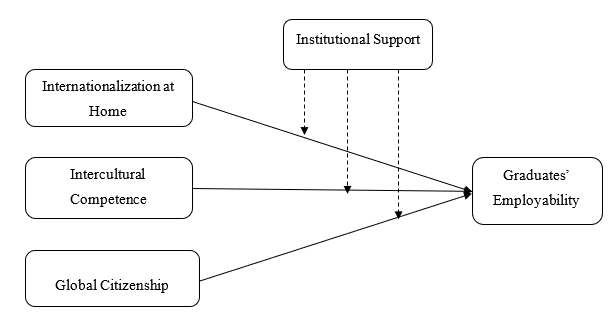

Internationalization at home, intercultural competence, and global citizenship play a vibrant role in developing graduates’ employability for graduates. The present study developed a framework with the consideration of three independent variables such as internationalization at home, intercultural competence, and global citizenship. The dependent variable is the graduates’ employability in the context of Malaysian graduates. Moreover, the study also aims to examine the effects of institutional support as a moderator on the relationship between internationalization at home, intercultural competence, global citizenship, and graduates’ employability. Hence, the current study proposed a research framework presented in figure

Conclusion

Graduates' employability has become a popular topic for scholars and industrial experts who consider it as a useful tool for developing a responsive diversity of human capital to fulfill the needs of modern jobs (Deardorff et al., 2012; De Wit, 2011; Killick, 2014). However, still, a scarcity of research is noticeable, particularly in developing and emerging nations such as Malaysia. This study thus contributed to the literature by clarifying the strength of the relationship between internationalization at home, intercultural competence, global citizenship, and employability of Malaysian graduates. It also offered institutional support as a significant moderator which have the potential to strengthen the relationship between key determinants of graduates’ employability. More empirical research is encouraged to investigate the proposed model by gathering information from a primary source and by analyzing the possible relations. though, the proposed model centred on the Malaysian universities and suggested for further studies are required to test the generalizability of findings in other countries.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge and highly appreciate the School of Management, Universiti Sains Malaysia for their enormous support in publishing my research.

References

- Abas, M. C., & Imam, O. A. (2016). Graduates' Competence on Employability Skills and Job Performance. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 5(2), 119-125.

- Ali, J. (2019). The effectiveness of finishing school programmes from the perspectives of graduates and employers. Malaysian Journal of learning and instruction, 11, 147-170.

- Al-Mutairi, A., Naser, K., & Saeid, M. (2014). Employability factors of business graduates in Kuwait: Evidence from an emerging country. International Journal of Business and Management, 9(10), 49.

- Andrews, G., & Russell, M. (2012). Employability skills development: strategy, evaluation and impact. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 2(1), 33-44.

- Angelova, M., & Zhao, Y. (2016). Using an online collaborative project between American and Chinese students to develop ESL teaching skills, cross-cultural awareness and language skills. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29(1), 167-185.

- Anho, J. E. (2011). An evaluation of the quality and employability of graduates of Nigeria Universities. African Journal of Social Sciences, 1(1), 179-185.

- Arrowsmith, C., Bagoly-Simó, P., Finchum, A., Oda, K., & Pawson, E. (2011). Student employability and its implications for geography curricula and learning practices. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 35(3), 365-377.

- Asonitou, S. (2015). Employability skills in higher education and the case of Greece. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 175, 283-290.

- Aulakh, P. S., & Kotabe, M. (1997). Antecedents and performance implications of channel integration in foreign markets. Journal of International Business Studies, 28(1), 145-175.

- Ayoubi, R. M., Alzarif, K., & Khalifa, B. (2017). The employability skills of business graduates in Syria: do policymakers and employers speak the same language?. Education+ Training, 59(1), 61-75.

- Barefoot, B. O. (2004). Higher education's revolving door: Confronting the problem of student drop out in US colleges and universities. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 19(1), 9-18.

- Barker, M. C., & Mak, A. S. (2013). From classroom to boardroom and ward: Developing generic intercultural skills in diverse disciplines. Journal of Studies in International Education, 17(5), 573-589.

- Beelen, J., & De Wit, H. (2012). Internationalisation revisited: New dimensions in the internationalisation of higher education. Centre for Applied Research on Economics and Management (CAREM).

- Bello, H., Shu’aibu, B., Saud, M. S., & Buntat, Y. (2013). ICT skills for technical and vocational education graduates’ employability. World Applied Sciences Journal, 23(2), 204-207.

- Belwal, R., Priyadarshi, P., & Al Fazari, M. H. (2017). Graduate attributes and employability skills: Graduates’ perspectives on employers’ expectations in Oman. International Journal of Educational Management, 31(6), 814-827.

- Bridgstock, R. (2009). The graduate attributes we’ve overlooked: Enhancing graduate employability through career management skills. Higher Education Research & Development, 28(1), 31-44.

- British Council (2013). Culture at Work: the Value of Intercultural Skills in the Workplace. British Council.

- Burke, C., Scurry, T., Blenkinsopp, J., & Graley, K. (2017). Critical perspectives on graduate employability. In Graduate employability in context (pp. 87-107). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cai, Y. (2013). Graduate employability: A conceptual framework for understanding employers’ perceptions. Higher Education, 65(4), 457-469.

- Chan, J. K. L. (2011). Enhancing the employability of and level of soft skills within tourism and hospitality graduates in Malaysia: The Issues and challenges. Journal of Tourism, 12(1).

- Ciriaci, D., & Muscio, A. (2014). University choice, research quality and graduates' employability: Evidence from Italian national survey data. European Educational Research Journal, 13(2), 199-219.

- Clarke, M. (2018). Rethinking graduate employability: The role of capital, individual attributes and context. Studies in Higher Education, 43(11), 1923-1937.

- Coetzee, M. (2017). Graduates’ psycho-social career preoccupations and employability capacities in the work context. In Graduate employability in context (pp. 295-315). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Coetzee, M., Ferreira, N., & Potgieter, I. L. (2015). Assessing employability capacities and career adaptability in a sample of human resource professionals. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(1), 1-9.

- de Guzman, A. B., & Choi, K. O. (2013). The relations of employability skills to career adaptability among technical school students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 82(3), 199-207.

- De Wit, H. (2011). Globalisation and internationalisation of higher education. Internationalisation of universities in the network society, 8(2).

- Deardorff, D. K., de Wit, H., Heyl, J. D., & Adams, T. (Eds.). (2012). The SAGE handbook of international higher education. Sage.

- Di Pietro, G. (2015). Do study abroad programs enhance the employability of graduates?. Education Finance and policy, 10(2), 223-243.

- Di Pietro, G. (2019). University study abroad and graduates’ employability, IZA World of Labor, 109, 1-10.

- Eurico, S. T., Da Silva, J. A. M., & Do Valle, P. O. (2015). A model of graduates׳ satisfaction and loyalty in tourism higher education: The role of employability. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 16, 30-42.

- European Commission (2014). The Erasmus Impact Study: Effects of mobility on the skills and employability of students and the internationalisation of higher education institutions. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Farčnik, D., & Domadenik, P. (2012). Has the Bologna reform enhanced the employability of graduates? Early evidence from Slovenia. International journal of manpower, 33(1), 51-75.

- Fatima, W.N., & Ameen, K. (2011). Employability skills of LIS graduates in Pakistan: needs and expectations. Library Management, 32(3), 209-224.

- Fenta, H. M., Asnakew, Z. S., Debele, P. K., Nigatu, S. T., & Muhaba, A. M. (2019). Analysis of supply side factors influencing employability of new graduates: A tracer study of Bahir Dar University graduates. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 10(2), 67.

- Finch, D. J., Hamilton, L. K., Baldwin, R., & Zehner, M. (2013). An exploratory study of factors affecting undergraduate employability. Education+ Training, 55(7), 681-704.

- Finch, D. J., Peacock, M., Levallet, N., & Foster, W. (2016). A dynamic capabilities view of employability: Exploring the drivers of competitive advantage for university graduates. Education+ Training, 58(1), 61-81.

- Fink, A. (1998). Conducting literature research reviews: from paper to the Internet. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Fletcher, A. J., Sharif, A. W. A., & Haw, M. D. (2017). Using the perceptions of chemical engineering students and graduates to develop employability skills. Education for Chemical Engineers, 18, 11-25.

- Freeman, M. Treleaven, L. Ramburuth B. P. (2009). Embedding the development of intercultural competence in business education. http://www.altc.edu.au/project-embedding-developmentintercultural-sydney-2006.

- González-Romá, V., Gamboa, J. P., & Peiró, J. M. (2018). University graduates’ employability, employment status, and job quality. Journal of Career Development, 45(2), 132-149.

- Green, W. (2012). The impact of friendship groups on the intercultural learning of Australian students abroad. International students negotiating higher education: Critical perspectives, 211.

- Greenwood, P. E., O’leary, K., & Williams, P. (2015). The Paradigm Shift: Redefining Education. Deolitte.

- Hanapi, Z., & Nordin, M. S. (2014). Unemployment among Malaysia graduates: Graduates’ attributes, lecturers’ competency and quality of education. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 112(2014), 1056-1063.

- Harvey, N., & Shahjahan, M. (2013). Employability of Bachelor of Arts graduates. Office for Learning and Teaching.

- Hasan, A., Mohd, S. N. T., & Yunus, M. F. M. (2016). Technical competency for diploma in mechatronic engineering at polytechnics Malaysia. International Review of Management and Marketing, 6(4S).

- Helyer, R., & Lee, D. (2014). The role of work experience in the future employability of higher education graduates. Higher Education Quarterly, 68(3), 348-372.

- Hinchliffe, G. W., & Jolly, A. (2011). Graduate identity and employability. British Educational Research Journal, 37(4), 563-584.

- Holmes, L. (2013). Competing perspectives on graduate employability: possession, position or process?. Studies in Higher Education, 38(4), 538-554.

- Huang, R. (2013). International experience and graduate employability: Perceptions of Chinese international students in the UK. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 13, 87-96.

- Humburg, M., Van der Velden, R., & Verhagen, A. (2013). The employability of higher education graduates. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Hunt, I., Brien, E. O., Tormey, D., Alexander, S., Mc Quade, E., & Hennessy, M. (2013). Educational programmes for future employability of graduates in SMEs. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, 24(3), 501-510.

- Ismail, R., Yussof, I., & Sieng, L. W. (2011). Employers’ perceptions on graduates in Malaysian services sector. International Business Management, 5(3), 184-193.

- Jackling, B., & Natoli, R. (2015). Employability skills of international accounting graduates: Internship providers’ perspectives. Education+ Training, 57(7), 757-773.

- Jackson, D. (2016). Re-conceptualising graduate employability: the importance of pre-professional identity. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(5), 925-939.

- Jackson, D., & Chapman, E. (2012). Non-technical skill gaps in Australian business graduates. Education+ Training, 54(2/3), 95-113.

- Jones, E. (2013). Internationalization and employability: The role of intercultural experiences in the development of transferable skills. Public Money & Management, 33(2), 95-104.

- Khirotdin, R. K., Ali, J. M., Nordin, N., & Mustaffa, S. E. S. (2019). Intensifying the Employability Rate of Technical Vocational Education and Training (Tvet) Graduates: A Review of Tracer Study Report. Journal of Industry, Engineering and Innovation, 1(1).

- Killick, D. (2014). Developing the global student: Higher education in an era of globalization. Routledge.

- Killick, D. (2017). Internationalization and Diversity in Higher Education: Implications for Teaching, Learning and Assessment. Palgrave.

- Knight, J. (2008). The internationalization of higher education: Complexities and realities. Higher education in Africa: The international dimension, 1-43.

- Lambert, J., & Usher, A. (2013). Internationalization and the Domestic Student Experience. Higher Education Strategy Associates.

- Lau, H. H., Hsu, H. Y., Acosta, S., & Hsu, T. L. (2014). Impact of participation in extra-curricular activities during college on graduate employability: an empirical study of graduates of Taiwanese business schools. Educational Studies, 40(1), 26-47.

- Matsouka, K., & Mihail, D. M. (2016). Graduates’ employability: What do graduates and employers think?. Industry and Higher Education, 30(5), 321-326.

- Messum, D., Wilkes, L., & Jackson, D. (2015). What employability skills are required of new health managers?. Asia Pacific Journal of Health Management, 10(1).

- Minten, S., & Forsyth, J. (2014). The careers of sports graduates: Implications for employability strategies in higher education sports courses. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 15, 94-102.

- Mtawa, N., Fongwa, S., & Wilson-Strydom, M. (2019). Enhancing graduate employability attributes and capabilities formation: a service-learning approach. Teaching in Higher Education, 1-17.

- Nilsson, B. (2003). Internationalisation at home from a Swedish perspective: The case of Malmö. Journal of studies in International Education, 7(1), 27-40.

- Nilsson, P. A., & Ripmeester, N. (2016). International student expectations: Career opportunities and employability. Journal of International Students, 6(2), 614-631.

- Nilsson, S. (2010). Enhancing individual employability: the perspective of engineering graduates. Education+ Training, 52(6/7), 540-551.

- Nisha, S. M., & Rajasekaran, V. (2018). Employability skills: A review. IUP Journal of Soft Skills, 12(1), 29-37.

- O’Leary, S. (2017). Graduates’ experiences of, and attitudes towards, the inclusion of employability-related support in undergraduate degree programmes; trends and variations by subject discipline and gender. Journal of Education and Work, 30(1), 84-105.

- Omar, N. H., Manaf, A. A., Mohd, R. H., Kassim, A. C., & Aziz, K. A. (2012). Graduates' employability skills based on current job demand through electronic advertisement. Asian Social Science, 8(9), 103.

- Orence, A., & Laguador, J. M. (2013). Employability of Maritime Graduates of Lyceum of the Philippines University from 2007-2011. International Journal of Research in Social Sciences, 3(3), 142.

- Ornellas, A., Falkner, K., & Stålbrandt, E. E. (2019). Enhancing graduates’ employability skills through authentic learning approaches. Higher education, skills and work-based learning, 9(1), 107-120.

- Osmani, M., Weerakkody, V., Hindi, N., & Eldabi, T. (2019). Graduates employability skills: A review of literature against market demand. Journal of Education for Business, 94(7), 423-432.

- Pavlin, S., & Svetlik, I. (2014). Employability of higher education graduates in Europe. International Journal of Manpower, 35(4), 418-424.

- Peterson, F. (2016). Media education for the global workplace: Developing employability skills through digital learning. Media Education Research Journal, 6(2), 55-73.

- Pheko, M. M., & Molefhe, K. (2017). Addressing employability challenges: A framework for improving the employability of graduates in Botswana. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 22(4), 455-469.

- Pinto, L. H., & Ramalheira, D. C. (2017). Perceived employability of business graduates: The effect of academic performance and extracurricular activities. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 99, 165-178.

- Poon, J. (2012). Real estate graduates’ employability skills: the perspective of human resource managers of surveying firms. Property management, 30(5), 416-434.

- Poon, J. (2014). Do real estate courses sufficiently develop graduates’ employability skills? Perspectives from multiple stakeholders. Education+ Training, 56(6), 562-581.

- Pouratashi, M., & Zamani, A. (2019). University and graduates employability: Academics’ views regarding university activities (the case of Iran). Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 9(3), 290-304. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-12-2017-0103

- Puhakka, A., Rautopuro, J., & Tuominen, V. (2010). Employability and Finnish university graduates. European Educational Research Journal, 9(1), 45-55.

- Ramadi, E., Ramadi, S. and Nasr, K. (2015). Engineering graduates’ skill sets in the MENA region: a gap analysis of industry expectations and satisfaction. European Journal of Engineering Education, 41(1), 34–52.

- Rao, M. S. (2015). Employers hire for attitude and train for skill: Enthusiastic candidates often land the offer of a job. Human Resource Management International Digest, 23(4), 33-34.

- Robles, M. M. (2012). Executive perceptions of the top 10 soft skills needed in today’s workplace. Business Communication Quarterly, 75(4), 453-465.

- Saad, M. S. M., & Majid, I. A. (2014). Employers’ perceptions of important employability skills required from Malaysian engineering and information and communication technology (ICT) graduates. Global Journal of Engineering Education, 16(3), 110-115.

- Saleh, H. (2019). Employer Satisfaction With Engineering Graduates Employability: A Study Among Manufacturing Employers In Malaysia. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research, 8(9), 819-817.

- Sapaat, M. A., Mustapha, A., Ahmad, J., Chamili, K., & Muhamad, R. (2011). A data mining approach to construct graduates employability model in Malaysia. International Journal on New Computer Architectures and Their Applications, 1(4), 1086-1098.

- Sarkar, M., Overton, T., Thompson, C., & Rayner, G. (2016). Graduate employability: Views of recent science graduates and employers. International Journal of Innovation in Science and Mathematics Education (formerly CAL-laborate International), 24(3).

- Schech, S., Kelton, M., Carati, C., & Kingsmill, V. (2017). Simulating the global workplace for graduate employability. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(7), 1476-1489.

- Schomburg, H. (2011). Employability and mobility of bachelor graduates: the findings of graduate surveys in ten European countries on the assessment of the impact of the Bologna Reform. In Employability and mobility of Bachelor graduates in Europe (pp. 253-273). Brill Sense.

- Seth, D., & Seth, M. (2013). Do soft skills matter? – Implications for educators based on recruiters’ perspective. IUP Journal of Soft Skills, 7(1), 7–20.

- Shafie, L. A., & Nayan, S. (2010). Employability awareness among Malaysian undergraduates. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(8), 119.

- Shanmugam, M. (2017). Unemployment among graduates needs to be sorted out fast. https://www.thestar.com.my/business/businessnews/2017/03/25/unemployment-among-graduates-needs-to-sorted-outfast/#RiCG76Js3EuH2e9u.99

- Shumilova, Y., Cai, Y., & Pekkola, E. (2012). Employability of international graduates educated in Finnish higher education institutions. VALOA-project, Career Services, University of Helsinki.

- Sin, C., Tavares, O., & Amaral, A. (2016). Who is responsible for employability? Student perceptions and practices. Tertiary Education and Management, 22(1), 65-81.

- Smith, S., Smith, C., Taylor-Smith, E., & Fotheringham, J. (2019). Towards graduate employment: exploring student identity through a university-wide employability project. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 43(5), 628-640.

- Soria, K. M., & Troisi, J. (2014). Internationalization at home alternatives to study abroad: Implications for students’ development of global, international, and intercultural competencies. Journal of studies in international education, 18(3), 261-280.

- Stiwne, E. E., & Alves, M. G. (2010). Higher education and employability of graduates: will Bologna make a difference?. European Educational Research Journal, 9(1), 32-44.

- Støren, L. A., & Aamodt, P. O. (2010). The quality of higher education and employability of graduates. Quality in Higher Education, 16(3), 297-313.

- Su, W., & Zhang, M. (2015). An integrative model for measuring graduates’ employability skills—A study in China. Cogent Business & Management, 2(1), 1060729.

- Succi, C. (2019). Are you ready to find a job? Ranking of a list of soft skills to enhance graduates' employability. International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management, 19(3), 281-297.

- Suleman, F. (2016). Employability skills of higher education graduates: Little consensus on a much-discussed subject. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 228, 169-174.

- Suleman, F. (2018). The employability skills of higher education graduates: insights into conceptual frameworks and methodological options. Higher Education, 76(2), 263-278.

- Sumanasiri, E. G. T., Yajid, M. S. A., & Khatibi, A. (2015). Review of literature on graduate employability. Journal of Studies in Education, 5(3), 75-88.

- Sutton, N. (2002). Why can’t we all just get along? Computing Canada, 28(16), 20.

- Teichler, U. (2011). Bologna–Motor or stumbling block for the mobility and employability of graduates?. In Employability and mobility of bachelor graduates in Europe (pp. 3-41). Brill Sense.

- Think Global (2011). The Global Skills Gap: Preparing Young People for the New Global Economy. Think Global.

- Tomlinson, M. (2010). Investing in the self: structure, agency and identity in graduates' employability. Education, Knowledge & Economy, 4(2), 73-88.

- Tomlinson, M. (2012). Graduate employability: A review of conceptual and empirical themes. Higher Education Policy, 25(4), 407-431.

- Tomlinson, M. (2017). Forms of graduate capital and their relationship to graduate employability. Education+ Training, 59(4), 338-352.

- Tran, T. T. (2015). Is graduate employability the ‘whole-of-higher-education-issue’?. Journal of Education and Work, 28(3), 207-227.

- Tymon, A. (2013). The student perspective on employability. Studies in higher education, 38(6), 841-856.

- Van Gaalen, A., & Gielesen, R. (2014). Internationalizing Students in the Home Country-Dutch policies. International Higher Education, 78, 10-12.

- Vázquez-Ingelmo, A., Cruz-Benito, J., García-Peñalvo, F. J., & Martín-González, M. (2018). Scaffolding the OEEU's Data-Driven Ecosystem to Analyze the Employability of Spanish Graduates. In Global Implications of Emerging Technology Trends (pp. 236-255). IGI Global.

- Wächter, B. (2003). An introduction: Internationalisation at home in context. Journal of studies in international education, 7(1), 5-11.

- Wang, Y. F., & Tsai, C. T. (2014). Employability of hospitality graduates: Student and industry perspectives. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 26(3), 125-135.

- Watkins, H., & Smith, R. (2018). Thinking globally, working locally: employability and internationalization at home. Journal of Studies in International Education, 22(3), 210-224.

- Wellman, N. (2010). The employability attributes required of new marketing graduates. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 28(7), 908-930.

- Wickramasinghe, V., & Perera, L. (2010). Graduates', university lecturers' and employers' perceptions towards employability skills. Education+ Training, 52(3), 226-244.

- Wilton, N. (2011). Do employability skills really matter in the UK graduate labour market? The case of business and management graduates. Work, employment and society, 25(1), 85-100.

- Xiao-qian, Y. E. (2011). Developing graduate employability: the experiences of UK and its implications [J]. Education Science, 2, 18-26.

- Yang, H., Cheung, C., & Fang, C. C. (2015). An empirical study of hospitality employability skills: perceptions of entry-level hotel staff in China. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 27(4), 161–170.

- Yizhong, X., Lin, Z., Baranchenko, Y., Lau, C. K., Yukhanaev, A., & Lu, H. (2017). Employability and job search behavior: A six-wave longitudinal study of Chinese university graduates. Employee Relations, 39(2), 223-239.

- Yoong, D., Don, Z. M., & Foroutan, M. (2017). Prescribing roles in the employability of Malaysian graduates. Journal of Education and Work, 30(4), 432-444.

- Zegwaard, K. E., & McCurdy, S. (2014). The influence of work-integrated learning on motivation to undertake graduate studies. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 15(1), 13-28.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

06 October 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-087-7

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

88

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1099

Subjects

Finance, business, innovation, entrepreneurship, sustainability, environment, green business, environmental issues

Cite this article as:

Khalid, J., Muhayidin, A., Ali, A. J., Mohd Nordin, N., & Khan, H. (2020). From A Literature Review To The Conceptual Framework For The Employability. In Z. Ahmad (Ed.), Progressing Beyond and Better: Leading Businesses for a Sustainable Future, vol 88. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 501-516). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.10.45