Abstract

Cross-border entrepreneurship contributes a positive spill-over effect to socio-economic growth in border regions through employment opportunities, wealth creation, better infrastructure, thus improving the standard of living in the border communities. Nevertheless, economic activities in a small border rural area tends to be less formal, which have been contended by many researchers due to several diplomatic issues, such as unclear demarcation of international borders and unequal pace of democratic development between neighbouring countries. Therefore, the study aims to explore the entrepreneurial activities in Sebatik Island, through preliminary site visits and informal conversations with local communities in two of the island’s borderline villages, i.e. Kampung Sungai Melayu and Kampung Aji Kuning by employing Rapid Ethnographic (RE) approach. The site visits provide interesting remarks about the prospects for cross-border entrepreneurship on the island. The study presents the current state of entrepreneurial activities in Sebatik Island and several emerging issues in relation to economic potential, such as the rise of informal business activities, business infrastructure, and government initiatives to support cross-border entrepreneurship on the island. This study provides valuable insights to relevant agencies responsible for rural entrepreneurial development, thus suitable measures or programs can be implemented in promoting formal cross-border entrepreneurship on the island.

Keywords: Cross-border entrepreneurshipinformal entrepreneursSebatik Island

Introduction

Cross-border entrepreneurship can be defined as a business activity across transnational border, in the form of cooperation or partnership, from informal petty to formal registered business ( Smallbone & Welter, 2012). It can be viewed as one of the potential economic activities that can be developed in border regions. Cross-border entrepreneurship between many neighbouring regions have been developing in the forms of social as well as economic cooperation. In less developed areas, the economic activities including the cross-border trade often occurs as micro-sized and in less formal way, in the absence of formal cooperation and partnership. From the government point of view, informal business although legitimate in terms of types of goods and services sold, is generally associated with social and economic problems ( Sunarya & Sudaryono, 2016; Thai & Turkina, 2014), for example, smuggling, transnational crime, tax revenue losses, productivity and growth implications, inequality and poverty. Notwithstanding, considering the deliberation of entrepreneurship, informal business can be regarded as an entrepreneurial action. Though informal, it is considered as a starting point for a venture development stage which requires initial preparation of obtaining resources before moving to a formal start-up ( Leach & Melicher, 2012). Informal entrepreneurship, therefore, should be treated as a business opportunity that are potential for income generation and job creation as it grows to a greater level. In Malaysia, entrepreneurship activity in the cross border plays a significant role in the socio-economic development in the country. The emergence of cross-border trade, including the informal sector will generate employment, create wealth and indirectly will stimulate the construction of better infrastructures ( Awang et al., 2013) and eventually improve the standard of living in the border communities. It is found that research on entrepreneurship in border community, especially between countries sharing their borders are not being explored sufficiently, particularly in rural areas. Therefore, through site visit and informal interviews with local communities in two of the island’s borderline villages, i.e. Kampung Sungai Melayu and Aji Kuning, this paper aims to explore the potential for cross-border entrepreneurship in two of the borderline villages in Sebatik Island (i.e. Kampung Sungai Melayu and Kampung Aji Kuning), which are popular as trading ports among the Malaysia-Indonesia border communities. This paper starts with observing activities in two villages and other nearby villages in the Island, then identifying emergent issues relating to cross-border economic activities in Sebatik Island (Malaysia-Indonesia border).

Sebatik Island – A land of two nations

Sebatik Island, an island of two countries, bisected by the Indonesian and Malaysian border, with Malaysia in the east region (204.7 square kilometres), and Indonesia in the west (452.2 square kilometres). Sebatik Malaysia is within the administrative division of Tawau, consisting of several villages namely, Kampung Wallace Bay, Kampung Mentadak Baru, Kampung Sungai Tongkang, Kampung Bogosong and Kampung Sungai Pukul ( Mahali & Isnain, 2018). Most of the residents in Sebatik Malaysia are fishermen, farmer and loggers. There are two villages located at the Malaysia-Indonesia border of the island, which are also the trading ports between Malaysia and Indonesia, i.e. Kampung Sungai Melayu and Kampung Aji Kuning. Figure

Sebatik Island was one of the islands which received heavy fighting between Indonesian and Malaysian during the 1963 Indonesia–Malaysia Confrontation. Today, there are about 8,000 people of different ethnicities; mostly Bugis, Bajau and Tidong live on Sebatik Malaysia. Meanwhile, the population of Sebatik Indonesia is said to be ten times of Sebatik Malaysia. The socio-economic activity of the Sebatik people had always been connected to Malaysia, especially to Tawau, Sabah, through its economic relations and cultural ties ( Puryanti & Husain, 2011). The Malaysian Sebatik has been receiving government support for local economic development in the island. Nevertheless, the ambiguity of the borders leads to disputes between two neighbouring countries until today. In fact, during the authors’ visit, it was surprising to see only Sebatik Indonesia placing their border guards on the island, but not for Sebatik Malaysia. This implies the situation of socio-economic activities between two border communities, i.e. free entrance to Malaysia by Indonesian, but not for Malaysian to Indonesia.

Problem Statement

The growth of entrepreneurial activities in small remote border areas may inspire the development of cross-border entrepreneurship, contributing to the improvement of the socio-economic condition in deprived regions. Many scholars of cross-border trades have conceptualised cross-border entrepreneurship by its own term ‘cross-border’, which means business activity that takes place beyond international borders, with regular and continuous contact between traders on both side of the borders, which may include various forms of partnerships ( Smallbone & Welter, 2012). It is a joint initiative involving several partners representing entrepreneurs, non-government agencies and government agencies, aimed to build economic cooperation between border regions. Nevertheless, often, small entrepreneurs in remote border villages do not register their businesses on the other side of the border, though they sell goods or buy raw materials to (or from) neighbouring region ( Awang et al., 2013; Smallbone & Welter, 2012). Cross-border entrepreneurship is often proposed by governments as an incentive for economic growth. Many studies found that cross-border entrepreneurship lead to significant economic benefits for local communities through income generation, employment opportunities and some local economic linkages ( Bariyah et al., 2012; Hampton, 2010).

Cross-border entrepreneurship benefits the entrepreneurs or traders through gaining new markets, exposure to new business networks and having ease of access to source of capital (e.g. labour, raw materials and finance). In fact, in many developing regions, cross-border entrepreneurship, including cross-border informal trade, has been regarded as one of the mechanisms to develop economic growth of the local community ( Aralas et al., 2017; Bariyah et al., 2012). Nevertheless, many previous researches highlighted several common strategic issues pertaining cross-border entrepreneurship in Malaysia, including socio-economic vulnerability, security, ethnic relations, and business practice differences ( Awang et al., 2013; Sunarya & Sudaryono, 2016; Thai & Turkina, 2014). For example, the Malaysia-Indonesia border in the Sarawak-Kalimantan region, faced myriad of issues, and became socio-politically vulnerable, that led to border conflicts between Malaysia and Indonesia. Some studies also found that, when it comes to economic activity, there is still lack of formal rules or borders for both neighbouring countries, the most significant to border community is as long as the market society can work together for an economic sustainability ( Puryanti & Husain, 2011; Rudiatin, 2016). It is crucial to understand how entrepreneurial activities in the border villages take place regardless of the absence of formal rules imposed. In addition, it is found that study on entrepreneurship in the small remote border areas, especially the informal cross-border trade receives less attention compared to developed areas ( Ngah, 2012; Sunarya & Sudaryono, 2016) and not being researched sufficiently. Most research on Sebatik Island borderland have been concentrating on anthropological and political study ( e.g. Puryanti & Husain, 2011; Rudiatin, 2016), and none on entrepreneurship. Therefore, this paper discusses the entrepreneurial activities in small remote border villages in Sebatik Island of Malaysia-Indonesia borders, by gathering views from the local entrepreneurs in Sebatik Island, Malaysia on opportunities and challenges of cross-border entrepreneurship in Sebatik Island.

Research Questions

This study aims to explore from the point of view of villagers in two border villages in Sebatik Island, i.e. Kampung Sungai Melayu and Kampung Aji Kuning, on the following research questions: -

What is the current condition of entrepreneurial activities in the border villages of Sebatik Island? What are the emerging issues of cross-border entrepreneurship in the border villages of Sebatik Island?

Purpose of the Study

This study aims to explain the emerging issues of the Malaysian-Indonesian border villages in Sebatik Island, in relating to opportunities and challenges of entrepreneurship activity between two countries, by considering the existing territorial rules and borders, as well as business infrastructure available for communities in the border villages. This study recommends valuable insights to mandated agencies for entrepreneurship development in rural borders, especially in terms of policy and procedures.

Research Methods

This study is a part of a larger research works under the Small Island Research Centre (SIRC), Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS), sought to provide preliminary insights on entrepreneurial activities in Sebatik Island, Malaysia. For the purpose of the study, Rapid Ethnography (RE) approach was employed due to limited time frame given for conducting the study without violating the underlying ethnographic principle. RE technique has been enormously undertaken by researchers in computer studies, education, medicine, and marketing, but its application in entrepreneurship research is still limited ( Handwerker, 2001; Reeves et al., 2008). Unlike conventional ethnography, RE is a fast data collection technique which necessary when researcher has limited time to spend in the field to collect quality depth data ( Spradley 1980). Baines and Cunningham ( 2013) contend that eminent data can still be gathered though within short period of time. In order to compensate its limitation, Millen ( 2000) suggests the used of multiple data collection methods as time-deepening strategies when employing RE approach.

By employing Rapid Ethnography (RE), data were gathered through site visits, photo taking from observations and informal conversations with few locals in two most popular borderline villages in Sebatik Island, i.e. Kampung Sungai Melayu and Kampung Aji Kuning. As the interview was not included in the initial fieldwork plan, the respondents were approached when the authors met the headmen of both villages, and the conversations with them were conducted in an informal way, more to experience and opinion sharing. Puryanti and Husain ( 2011) employs this approach for their research on border-crossings in Sebatik Island, Indonesia, and present the data in narrative ways. Some of the villagers interviewed are small traders operating a grocery shops, bakery shops and used-clothes shops (bundle store), fishermen, and plantation workers. Related photos on entrepreneurial activities were taken during observations to support the data. Angrosino and Mays de Perez ( 2000) mentioned that observations in natural settings can be the most powerful source of validation, rests on researchers’ direct knowledge and own judgement. All data gathered from this study were based on subjective perceptions by entrepreneurs about current entrepreneurial activities, issues and opportunities for cross-border entrepreneurship. All views from the respondents were analysed and presented into a preliminary insight befitting the research aim, i.e. to share the experience and views of entrepreneurs in Sebatik Island border villages about prospects of cross-border entrepreneurship.

Findings

Entrepreneurial activities in Sebatik Island – The current status

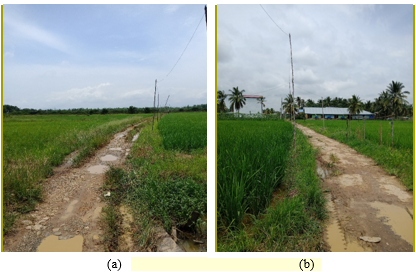

Based on the authors’ visits to two of the island’s small remote border villages, Kampung Sungai Melayu and Kampung Aji Kuning, it is realised that Sebatik in Indonesia is more rapidly thriving than in Malaysia in terms of its socio-economic development, primarily due to active involvement in entrepreneurial activity. The entrepreneurial activities in Sebatik Island, near Malaysia-Indonesia boundary can be recognised from several informal activities among border communities, including sales of goods, transportation services as well as small tourism-related products. For examples, from authors’ observation, some of the locals of Indonesia Sebatik run an informal shuttle that transport goods and people using motorcycle from Malaysia jetty to Indonesia territory in the island (or so-called grab-bike) via informal route or popular as ‘jalan tikus’ among the locals in Kampung Sungai Melayu (Figure

Besides, authors’ observation near Malaysia-Indonesia borderline found that there were so many street shops in Indonesia Sebatik as compared to in Malaysia Sebatik in both villages studied (Figure

Based on the site visit, Sebatik Island can be potentially developed as a small tourism village, for example, the unique house in Kampung Aji Kuning, which owned by a Malaysian family that have been settling exactly on the International borderline of Malaysia-Indonesia. Amazingly, the kitchen area is in Malaysia territory, while the living room is sited in Indonesian land (Figure

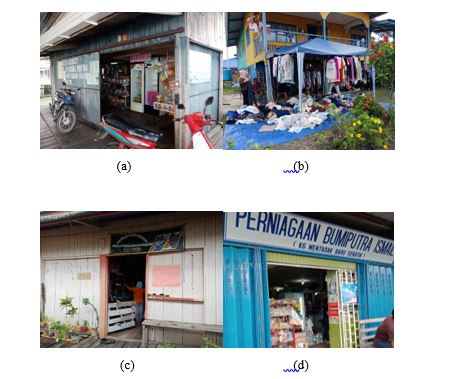

Based on the authors’ observation, the economic activity in borderline villages (i.e. Kampung Sungai Melayu and Aji Kuning) is not as fast growing as in other non-borderline villages in Sebatik Island. For example, based on the interviews with some of Malaysian in Kg Mentadak Baru, there were several small business activities run by the villagers, like bundle shop, cake and bakery, fishing, guest house, transportation services, and even exchange of goods for food items and necessities (Figure

The emerging issues of cross-border entrepreneurship in Sebatik Island

Authors’ site visits to Kampung Sungai Melayu and Aji Kuning discovered several issues related to entrepreneurial activities in the border villages. The first emergent issue involves the unbalanced economic growth between Malaysia Sebatik and Indonesia Sebatik. The economic activity in Malaysia Sebatik is shrinking, due to aging people and the young leaving the village to work in the city. The current activities run by the villagers are micro-sized proprietor business like bundle shop, cake and bakery, fishing, guest house, boating and driving services, and even exchange goods for food items and necessities. Whereas in Indonesia Sebatik, the economy seems more growing, and can be seen from the growing number of factories and brick shops at the border village of Aji Kuning and Kampung Sungai Melayu. The second issue relates to the emergence several informal cross-border economic activities among local people in Sebatik Island, near Malaysia-Indonesia boundary, such as informal shuttles that transport goods and people by motorcycle from Malaysian jetty, to Indonesian mainland in the island (grab transportation), selling and buying goods in Aji Kuning, Indonesia using Ringgit Malaysia for transactions, and potential small tourism attraction in Aji Kuning, Malaysia when where a house of a Malaysian family have been settling exactly on the International border Malaysia-Indonesia, there is possibilities for attraction due to its uniqueness, i.e. the kitchen area is located in Malaysia terrestrial, while the living room is located in Indonesian land.

The third issue relates to the unequal pace of democracy in both border villages. Based on the authors’ observation, despite resembling common religion, language and cultural heritage, both countries have been undertaking unequal pace of democracy which may lead to serious bilateral pressures. The Indonesian government have defended its country through security approach as compared to Malaysia that use both the welfare (prosperity) and security approach ( Sunarya & Sudaryono, 2016). Stringent border controls have been imposed by the Indonesian government on each of its international borders, for example in Sebatik Island, the Indonesian military forces (Tentera Nasional Indonesia) and security post has been positioned at the Indonesia border near the jetty of Aji Kuning, to control illegal visitors. Unlike Indonesian border, at the Malaysian border, there is no formal Malaysia security guard post, no immigration security or custom officer, in fact no fences or walls demarcating the border, which allows free movement of Indonesian people inbound and outbound of the Malaysian border. This issue can be regarded as unfair legal demarcated international border between Malaysia and Indonesia in Sebatik Island. In fact, this could be a hindrance to cross-border entrepreneurship development in both regions.

Conclusion

The study employed preliminary site visit for data collection method in order to explore the status of entrepreneurial activities in the area under investigation. The preliminary findings that contributes to the body of knowledge on the emerging issues and prospects of cross-border entrepreneurship in small island’s borderline villages in Sabah. Nevertheless, this study was limited to communities in several borderline villages in Sebatik Island. Furthermore, lack of systematic way for sample and location selection due to limited time for the site visit and accessibility issue to the borderline villages may have implications for the generalisability of the results, in terms of richness of data gathered from respondents. In order to compensate the drawbacks, multiple data collection technique was used, including informal conversation with the head of village, local communities as well as photo taking which support the findings. In addition, it is believed that the scope of the study in terms of the sample (local communities near borderline villages), geographic area (borderline villages in Sebatik Island) and field of study (current issues and prospects of cross-border entrepreneurship) can allow the findings to be adequately understood. Furthermore, there are some concerns relating to reliability and validity of data as the study undertook parsimonious qualitative technique, therefore, future research might be conducted via structured interview guide and systematic analytical techniques.

Notwithstanding, it is hoped that the study provides some valuable insights pertaining economic activities, the challenges and prospects for entrepreneurship activities in the borderline villages, i.e. in Kampung Sungai Melayu and Kampung Aji Kuning in Sebatik Island. Literature has contended that cross-border entrepreneurship contributes to the development of the regions and also to individual businesses. The current situation in the border villages of Sebatik Island can be said as still lack of continuous formal government supports on cross-border entrepreneurship rules and infrastructures. The intermittent assistance or supports from outside agencies will not always sustain the economy of the local people for long term. Nijkamp ( 2003) mentioned external supports from external institutions per se may not always promise successful entrepreneurial development. Terluin ( 2003) proposes that entrepreneurship development happens as a result of local people being stimulated to develop enterprises based on local resources in their area. Therefore, it is important for the related agencies to assist the border communities to create income from their own local resources, which will eventually provide significant changes in economic status in the border villages. In addition, by identifying the emergent issues relating to cross-border economic activity in Sebatik Island of Malaysia and Indonesia, this paper hopes to provide some insights to related agencies in both countries, to develop effective support measures to encourage formal cross-border entrepreneurship in the island.

Acknowledgments

This research was sponsored by Universiti Malaysia Sabah through Small Island Research Centre (SIRC), under the Top-Down Research Grant (STD0012-2016). Appreciation goes to all local communities of Sebatik Island who have been involved in this study, for their invaluable assistance during data collection stage.

References

- Angrosino, M.V., & Mays de Perez, K.A. (2000). Rethinking observation: From method to context. In N.K. Denzin, & Y.S Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd Edition, (pp. 673-702). Sage, Thousand Oaks.

- Aralas, S., Abu Bakar, M. A. A., & Chan, K. L. (2017). The effects of barter trade suspension in Sabah. Journal of BIMP-EAGA Regional Development, 3(2), 13-22.

- Awang, A. H., Sulehan, J., Abu Bakar, N. R., Abdullah, M. Y., & Liu, O. P. (2013). Informal cross border trade Sarawak (Malaysia)-Kalimantan (Indonesia): A catalyst for border community’s development. Asian Social Science, 9(4), 167-173.

- Baines, D., & Cunningham, I. (2013). Using comparative perspective rapid ethnography in international case studies: Strengths and challenges. Qualitative Social Work, 12(1), 73-88.

- Bariyah, N., Lau, E., & Mansor, S. A. (2012). Long run sustainability of Sarawak - West Kalimantan cross-border trade flows. Journal of Developing Areas, 46(1), 165-181.

- Block, J., & Wagner, M. (2010). Necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs in Germany: Characteristics and earnings differentials. Schmalenbach Business Review, 62(2), 154-174.

- Hampton, M. P. (2010). Enclaves and ethnic ties: The local impacts of Singaporean cross‐border tourism in Malaysia and Indonesia. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 31(2), 239-253.

- Handwerker, W. P. (2001). Quick Ethnography: A Guide to Rapid Multi-Method Research. AltaMira Press.

- Leach, J. C., & Melicher, R. W. (2012). Entrepreneurial finance. Cengage Learning.

- Mahali. S. N., & Isnain, Z. (2018). Sebatik Island: The land of two sovereignty. In C. G. Joseph (Eds.), SIRC Newsletter (pp. 12-13). Small Island Research Centre.

- Millen, D. R. (2000). Rapid ethnography: Time deepening strategies for HCI field research. In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on designing interactive systems: processes, practices, methods, and techniques (pp. 280-286). ACM.

- Nasiri, N., & Hamelin, N. (2019). Entrepreneurship driven by opportunity and necessity: Effects of educations, gender and occupation in MENA. Asian Journal of Business Research, 8(2), 12-18.

- Ngah, I. (2012). Rural transformations development. In the International Conference on Social Sciences & Humanities (pp. 1-11). UKM.

- Nijkamp, P. (2003). Entrepreneurship in a modern network economy. Regional Studies, 37(4), 395-405.

- Puryanti, L., & Husain, S. B. (2011). A people-state negotiation in a borderland, A case study of the Indonesia-Malaysia frontier in Sebatik Island. Wacana, 13(1), 105-120.

- Reeves, S., Kuper, A., & Hodges, B. D. (2008). Qualitative research, Qualitative research methodologies: Ethnography, BMJ: British Medical Journal, 337(7668), 512-514.

- Rudiatin, E. (2016). The way of people in the borderland and exploiting island assets and maritime resources, (Study in Aji Kuning Village Sebatik Island North Kalimantan Province the Borderline of Indonesia and Sabah Malaysia). In Proceedings of the 2nd International Multidisciplinary Conference 2016 November. Universitas Muhammadiyah Jakarta.

- Smallbone, D., & Welter, F. (2012). Cross-border entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Regional Development International Journal, 24, 43-63.

- Spradley, J. P. (1980). Participant Observation. Holt, Rinehart and Winston Inc.

- Sunarya, A., & Sudaryono (2016). The strategic issues of economic development of border area of Indonesia – Malaysia (study case of Entikong sub-district of West Kalimantan). Cyberpreneurship Innovative and Creative Exact and Social Science, 2(2), 110 – 121.

- Terluin, I. J. (2003). Differences in economic development in rural regions of advanced countries: An overview and critical analysis of theories. Journal of Rural Studies, 19, 327-344.

- Thai, M. T. T., & Turkina, E. (2014). Macro-level determinants of formal entrepreneurship versus informal entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(4), 490-510.

- Zali, M. R., Faghih, N., Ghotbi, S., & Rajaie, S. (2013). The effect of necessity and opportunity driven entrepreneurship on business growth. International Research Journal of Applied and Basic Science, 7(2), 100-108.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

06 October 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-087-7

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

88

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1099

Subjects

Finance, business, innovation, entrepreneurship, sustainability, environment, green business, environmental issues

Cite this article as:

Fabeil, N. F., Marzuki, K. M., & Pusiran, A. K. (2020). Cross-Border Entrepreneurship: A Preliminary Study On Informal Entrepreneurs In Sebatik Island. In Z. Ahmad (Ed.), Progressing Beyond and Better: Leading Businesses for a Sustainable Future, vol 88. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 390-400). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.10.34