Abstract

This systematic review was designed to assess the previous studies related to consumers’ behaviours towards sustainability in a fashion that covers various fashion items including clothing, jewellery, general products, luxury items, and cosmetics. By following the PRISMA table, the reviewers had initiated this systematic review using the two databases which include Scopus and WOS. All the available articles were selected based on publications from the year 2015 to 2019. After reviewing the keywords, abstracts for the inclusion, exclusion process, and careful reading, a number of 45 papers were selected for reviewing. Further, the reviewer identifies and categories the selected articles based on four main themes of sustainable fashion namely, collaboration, eco-conscious, ethical or slow fashion and recycled and upcycled. The results from this review indicate that there is still a lack of research on sustainable fashion that covers clothing, jewellery and luxury items, as compared to cosmetics and general products such as food and cars. This review provides fruitful directions for future research on sustainable fashion.

Keywords: Collaborative fashioneco-conscious fashionethical/slow fashionrecycle/upcycle fashionsustainable fashion

Introduction

In the present century, fashion plays a pivotal role in most places around the world. According to Wiedmann et al. ( 2009), people have spent their entire lives by excessively focussing on others’ perceptions about fashion that they wear. The emergence of mass markets and the fluidity of demand have continuously changed this industry to a growing pace. In keeping up with the race in the fashion industry, designers never stop competing to create the next hit as consumers eagerly await the items. Despite providing consumers with the latest styles at low prices, this industry leaves behind a huge negative impact on the planet. The pollution contributed by various chemicals and pesticides used to grow cotton and toxic dyes are accumulating. Apart from the environmental footprints, this industry is also inextricably to gender inequality, labour injustice and poverty issues. The continuity of excessive pollution has in turn ranked this industry as the second biggest contributor of pollution came after oil and gas industry ( Qutab, 2017). Currently things seem to be changing. The seriousness of this issue has led fashion to be included in the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals on the agenda to transform the fashion industry by accelerating sustainability with a common framework of the global textile value and exploring many different efforts. Moreover, there is a rise in the number of scholars who claimed that there is a connection between fashion and sustainability ( Amatulli et al., 2018). The development of these trends has built a substantial buyer segment, colloquially known as ‘LOHAS’, which can be described as an inclination to practise a healthy and sustainable life ( Emerich, 2012). Leveraging on the customer’s interest, more companies are implementing sustainable fashion as the foundation for their businesses.

Problem Statement

Therefore, the motivation to consume sustainable product such as organic food and cosmetic is slightly different with sustainable apparel as the chosen of apparel involved with the development of appearance, self-confidence, style, and image ( Athwal et al., 2019). All the product categories should not be treated equally as it will lead them to just claiming their concern about the environment but do not translate this into action ( Scherer et al., 2018). Due to that, it is necessary to review the previous studies which had explored the motivational drivers of each sustainable fashion product differently.

Research Questions

The list of research questions derived for this review are:

What is the motivational drivers which triggered the customers to purchase sustainable fashion (based on specific country)?

What are the types of sustainable fashion?

Which sustainable fashion product are still lack of study?

Purpose of the Study

Therefore, this study aims for the first time to shed light on the consumers’ behaviours towards sustainability in fashion by systematically reviewing the literature covering various fashion items including clothing, jewellery, general products, luxury items, and cosmetics. Further, the reviewers had identified and categorised sustainable fashion into four specific main themes. Through the process, this review provides a beneficial in identifying the specific product that is still lacking in research based on different types of sustainable fashion.

After the introduction, the remaining of the paper is constructed as follows: Section

Research Methods

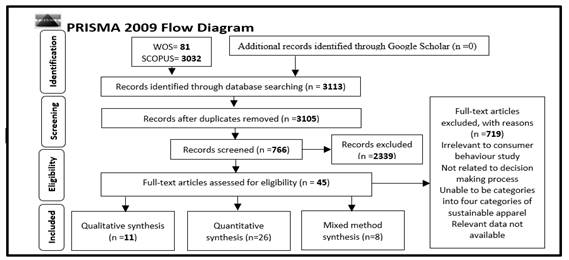

This systematic literature review was constructed by the following specific relevant criteria from PRISMA table ( Moher et al., 2009) (see Figure

Findings

The findings of the review are presented in a comprehensive four themes form on the different categories of sustainable fashion, including eco-fashion, ethical fashion, collaboration, and recycled/upcycled fashion. These categories of sustainable fashion are also supported by ( Brismar, 2019), who had classified sustainable fashion into seven forms (green and clean, custom made and on demand, timeliness design, ethical, upcycle, rent, lease, and second-hand fashion). Shen et al. ( 2013) strongly agreed with the statement and stated that from the fashion aspect, all terms labelled with organic, recycled, locally made, fair-trade certified, vegan, custom made and fair-trade certified are categorised as sustainable fashion. In answering all the research questions and knowledge gap, the reviewers had identified previous sustainable fashion studies which not only covered clothing but also include other categories of fashion (jewellery, general products, luxury items and cosmetics).

Further, the analysis results of the review show that the 45 research articles from 24 countries are summarised in Table

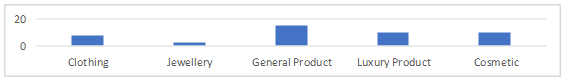

Figure

The next section will explain in depth about each fashion item according to the category of sustainable concepts covered in a different country. Finally, the reviewers will provide directions for future research in the perspective of sustainable fashion.

Collaborative fashion

Collaborative fashion can be defined as providing the consumers an option for the alternative of fashion instead of purchasing new fashion products ( Iran et al., 2019). There are various alternatives to the classic form of collaboration including swapping, renting and purchasing second-hand fashion. In regards to this systematic review, several scholars had specifically touched on collaboration in terms of clothing and discovered the level of acceptance in China, United States, Iran, and German ( Iran et al., 2019; Liang & Xu, 2018; Norum & Norton, 2017). Based on the research by Iran et al. ( 2019), Germany students were more engaged in collaborative fashion compared to the students in Iran. Germany students were more engaged in collaborative fashion compared to the students in Iran. This is due to the cultural differences between German and Iran, whereby German students are found to be shaping more on their feminine culture with power distance and lower uncertainty avoidance rates compared to the Iranian students. Meanwhile, the research conducted in the United States by Norum and Norton ( 2017) showed that consumers from Generation Y are labelled as a group who fully practise sustainability in fashion. This is due to the fact that this generation is willing to be entirely involved in second-hand, renting and swapping alternatives compared to Generation X, who are only attracted in consuming second-hand clothing which proves that collaborative is more prevalent and is becoming a new huge business opportunity there ( Liang & Xu, 2018).

On top of that, previous studies by Gaur et al. ( 2018); McNeill and Venter ( 2019) had looked into collaborative fashion as part of the general products in India, the Unites States and New Zealand. The cross-cultural study between United States and India revealed that the customers in United States have more eco-conscious value as compared to the Indian customers ( Gaur et al., 2018). The strong argument of difference is that customers from the United States were found to have more harmony orientation towards nature and follow the regulations more strictly. Meanwhile, the involvement of social norms, personal enhancement, and emotion play important roles in influencing the collaborative fashion consumption among the female consumers in New Zealand ( McNeill and Venter, 2019). Another research initiative regarding this topic covering the luxury item was conducted by ( Kessous & Valette-Florence, 2019; Onel et al. 2018; Turunen & Leipämaa-Leskinen, 2015). Turunen and Leipämaa-Leskinen ( 2015) postulated that the consumption of second-hand product in Finland were driven by five main factors which include sustainable selections, real deals, pre-loved treasures, unique finds and future investment. It can be said that the consumption of luxury second-hand brands is allied to green consciousness, product heritage and symbol of status compared to the first-hand luxury purchase which is more entailed to power-building, social ranking and quality ( Kessous & Valette-Florence, 2019). Throughout this systematic review, the reviewers realised that there is an absence of collaborative fashion-related research on jewellery and cosmetics. It may be difficult for both product categories to practice collaboration concepts (swapping, renting and buying second-hand), but it is possible with the availability of social media and online platforms such as Carousell, as it is able to connect the consumers in a wide network while enabling transactions of pre-loved and second-hand products.

Ethical and slow fashion

Ethical aspect has become a prominent concern since the occurrence of excessive consumption, labour abuse and ignorance of animal welfare ( Carrigan et al., 2004). On the one hand, the introduction of the slow fashion approach by Godart and Seong ( 2015) is synchronised with the movement of sustainability in fashion. Just like slow food, currently, slow fashion is quickly becoming the new black. Based on this systematic literature review, two studies covered the topic of ethics in apparel ( Bly et al., 2015; Brandão et al., 2018); two studies for jewellery ( Moraes et al., 2017; Nash et al., 2016); four studies for general products ( Cho et al., 2015; Jung & Jin, 2016; Lee & Cheon, 2018; Ritch, 2015); three studies for luxury items ( de Klerk et al., 2019; Dong et al., 2018; Jung et al., 2016) and one study for cosmetics ( Chun, 2016). The study conducted by Brandão et al. ( 2018) in South Western European countries had exposed that transparency of information does not subsequent a positive significant result. It is shown that retailers need to reduce the creations of the ephemeral fashion and start to implement the concepts of timeliness of style which gives more meaning to customers ( Bly et al., 2015). At the same time, de Klerk et al. ( 2019), discovered that most customers in South Africa expressed strong ethical concern about luxury products, but never transform it into real action. This is probably due to the excessive material possession and the love of owning luxury products ( Dong et al., 2018). Past studies related to cosmetics and personal body care also revealed that the ethical aspect, including honesty, trustworthiness, had left a minimal impact on the consumers’ emotional attachment in the United Kingdom ( Chun, 2016). This is due to the customers’’ limited consideration which is only to empathy and citizenship image.

In a different perspective, Nash et al. ( 2016) uncovered that over half of the respondents in the United States revealed that ethics-concerned messages are extremely or somewhat important to their jewellery-purchasing decisions. The inclusion of jewellery products with ethical concerns may result in the enhancements in terms of quality, value and uniqueness. Moraes et al. ( 2017) stated that to influence customers through ethical practice, there must be a strong linkage between ethical activities and the consumption practices of fine jewellery. Up to this point, the new practices of ethical luxury consumption are likely to succeed with the presence of innovation process involving the convergence of ethical materials and competencies. In terms of general products, customers in the United States were found to purchase ethical brand when they consider the elements of pragmatic benefit and sensory pleasure ( Cho et al., 2015; Jung & Jin, 2016; Lee & Cheon, 2018). The literature on ethical fashion also covers general products specified to food retailing. According to Ritch ( 2015), participants in the United Kingdom started to consider ethical production practice as part of their decision-making and supporting market preferences. Overall, previous studies show that ethical and slow fashion provide less and not significant impact on apparel, luxury items and cosmetic products. However, the fashion product categories such as jewellery and general products have a significant impact on the ethical and slow fashion concepts.

Eco-fashion

Environmentally fashion can be described as a fashion involving with an overall process that can maximise the benefits to all wherein minimise the carbon footprint impacts ( Joergens, 2006). Based on this systematic review, two studies were focussing on clothing ( Khare & Varshneya, 2017; Matthews & Rothenberg, 2017); four studies of general product ( Kim et al., 2016; Paparoidamis & Tran, 2019; Saleem et al., 2018; Shin et al., 2018); three studies of luxury items ( Ali et al., 2019; Fiore et al., 2017; Han et al., 2019), while nine studies were focussing on cosmetics ( Ahmad & Omar, 2018; Amos et al., 2019; Baden & Prasad, 2016; Chin et al., 2018; Ghazali et al., 2017; Hsu et al., 2017; Kahraman & Kazançoğlu, 2019; Ndichu & Upadhyaya, 2019; Pudaruth et al., 2015;). Past research by Khare and Varshneya ( 2017) show that relatives and friends are not important drivers in influencing the organic clothing purchase decisions of youths in India. It can be signifies that a decision to purchase this product is bonded based on personal pro environmental values and previous experience. Besides that, Matthews and Rothenberg ( 2017) found that customers in the United States were more concerned about sustainable materials, price and production, rather than the technology adopted. They prefer the eco-friendly labelling over organic labelling for apparels. In addition to that, four studies have discovered the eco-friendly general products. A past study carried out by Saleem et al. ( 2018) which explored the relationship between eco-conscious value and social interaction related to the choice and use of eco-personal cars in Pakistan showed a positive significant result. The findings of his study proved that there is a growing of preference towards environmentally friendly product selection in developing countries. Kim et al. (2016) and Paparoidamis and Tran ( 2019) share the same findings which revealed that promoting and marketing a new, eco-friendly faux leather product is a worthwhile prospect for the United States and the United Kingdom.

However, another research initiative by Shin et al. ( 2018) showed a negative relationship of eco-consciousness among customers in dealing to purchase the detergent‐free washing machines. Moving to green luxury products, several previous studies showed that consumers are started to put their attention on the concept of environmentally friendly and sustainable luxury involving wine, automobile and airplane services ( Ali et al., 2019; Fiore et al., 2017; Han et al., 2019). Most of them are the highly-educated customers and have vast information about environment-related issues. Moving on to organic cosmetics and personal care, a series of past studies exploring this topic, covering several countries, revealed that lifestyles practise, personal image, health and economic conditions are the factors that contribute to these purchasing patterns ( Ahmad & Omar, 2018; Amos et al., 2019; Chin et al., 2018; Ghazali et al., 2017; Pudaruth et al., 2015). Hsu et al. ( 2017) mentioned that the importance of exposing the country of origin, technology in production, and price to influence the eco conscious purchase intention. This review of the current literature reveals that previous scholars have examined numerous studies focussing on the organic cosmetics and environmentally friendly personal care that cover several countries, including the emerging and developing countries. Nevertheless, there is still a lack of studies, especially on the eco-conscious clothing and luxury products in the context of developing countries.

Recycled and upcycled fashion

The raw materials used in producing recycled garments can be attained through the accumulation of supply chain and post-consumer collection methods. It can be manifests that the adoption of recycled materials in a production is synchronise with the global effort to practices the movement to acquire a closed-loop production cycle. Meanwhile, the term “upcycling” was first coined by Kay ( 1994) which significantly elucidated the concept of adding value to used and old product, which slightly differs from the concept of recycling that cut the value of the products. Notably, upcycling is synonym to the creation of something new and upgrade the function better from old, used, or disposed items. In sum, the objective of upcycling is to focus on putting a value in a development process that are truly sustainable, creative, and innovative ( Muthu, 2016). Previous research has revealed the fact that customers evaluate the products made from recycled plastic positively ( Grönman et al., 2013; Magnier et al., 2019). Atlason et al. ( 2017) found that consumers support the effort to reuse the recycling textile waste to produce new garments and people older than 50 years old with higher education are seem to favour the integration of this sustainable product design. Yet, at the same, the Finnish and Canadian consumers also oftenly separate the basic recycled material (metal, paper, glass) and they practise it in the same ways for their garments collection ( Vehmas et al., 2018; Weber et al., 2017). As circular clothing is built based on new processes material so customers who avoid to wear second-hand fashion can optionally choose to purchase this circular garments. In part of commercialisation value, circular clothing should be more available on the market while at the same times be branded as luxury items and special editions. However, Rolling and Sadachar ( 2018) still argued the effectiveness of using recycled material on luxury items. Their research exposes that despite of putting recycled material as a brand descriptions, it is more effective to use sustainable message element in luxury marketing communication. From the systematic literature review, there are no previous research related to recycle and upcycle fashion implemented in jewellery and cosmetics. It happened due to the irrelevancy of those products to be practiced with this dimension of fashion.

Conclusion

The systematic review provides an insightful information about the consumers’ behaviours towards sustainability in fashion from different countries. At the same frequency, the results of the review were presented in four comprehensive themes based on the category of sustainable fashion which includes collaborative fashion, eco-conscious fashion, ethical fashion, and recycled/upcycled fashion. Taken together, all four dimensions of sustainable fashion are one way to respect the planet and to value what we already have. Despite a wider coverage of sustainable fashion, not everyone is able to practice all the various alternatives mentioned. Consumers have various options to acquire a fashion choice with pro-environmental attributes, so there is no excuse for not practising this clean fashion. It can be seen that sustainable fashion has the big potential to transform the entire fashion industry to positive movement, nevertheless the impact still depends on the prospect customers willingness to pay more for ethically produced clothing ¬and the readiness of brands to sacrifice profits and shift to sustainable. It was found that there is a lack of research in fashion products likes clothing, jewellery and luxury products, compared to cosmetics and general products like food and cars. For further exploration, it would be noteworthy to study this specific category of product. In addition, the future study can be conducted in an experimental study by considering how consumers react to a certain stimulus and all the ways that are able to influence their sustainable fashion consumption.

References

- Ahmad, S. N. B., & Omar, A. (2018). Influence of perceived value and personal values on consumers repurchase intention of natural beauty product. International Journal of Supply Chain Management, 7(2), 116–125.

- Ali, A., Xiaoling, G., Ali, A., Sherwani, M., & Muneeb, F. M. (2019). Customer motivations for sustainable consumption: Investigating the drivers of purchase behavior for a green-luxury car. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(5), 833-846.

- Amatulli, C., De Angelis, M., Korschun, D., & Romani, S. (2018). Consumers’ perceptions of luxury brands’ CSR initiatives: An investigation of the role of status and conspicuous consumption. Journal of Cleaner Production, 194, 277–287.

- Amos, C., Hansen, J. C., & King, S. (2019). All-natural versus organic: Are the labels equivalent in consumers’ minds? Journal of Consumer Marketing, 36(4), 516-526.

- Athwal, N., Wells, V. K., Carrigan, M., & Henninger, C. E. (2019). Sustainable luxury marketing: A synthesis and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 21(4), 405-426.

- Atlason, R. S., Giacalone, D., & Parajuly, K. (2017). Product design in the circular economy: Users’ perception of end-of-life scenarios for electrical and electronic appliances. Journal of Cleaner Production, 168, 1059–1069.

- Baden, D., & Prasad, S. (2016). Applying behavioural theory to the challenge of sustainable development: Using hairdressers as diffusers of more sustainable hair-care practices. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(2), 335–349.

- Bai, H., Wang, J., & Zeng, A. Z. (2018). Exploring Chinese consumers’ attitude and behavior toward smartphone recycling. Journal of Cleaner Production, 188, 227–236.

- Bly, S., Gwozdz, W., & Reisch, L. A. (2015). Exit from the high street: An exploratory study of sustainable fashion consumption pioneers. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39(2), 125–135.

- Brandão, A., Gadekar, M., & Cardoso, F. (2018). The impact of a firm’s transparent manufacturing practices on women fashion shoppers. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 9(4), 322–342.

- Brismar, A. (2019). Seven forms of sustainable fashion. http://www.greenstrategy.se/sustainable-fashion/seven-forms-of-sustainable-fashion/

- Carrigan, M., Szmigin, I., & Wright, J. (2004). Shopping for a better world? An interpretive study of the potential for ethical consumption within the older market. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 21(6), 401–417.

- Chin, J., Jiang, B. C., Mufidah, I., Persada, S. F., & Noer, B. A. (2018). The investigation of consumers’ behavior intention in using green skincare products: A pro- environmental behavior model approach. Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(11), 3922.

- Cho, E., Gupta, S., & Kim, Y. K. (2015). Style consumption: Its drivers and role in sustainable apparel consumption. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39(6), 661–669.

- Chun, R. (2016). What holds ethical consumers to a cosmetics brand: The Body Shop case. Business and Society, 55(4), 528–549.

- de Klerk, H. M., Kearns, M., & Redwood, M. (2019). Controversial fashion, ethical concerns and environmentally significant behaviour: The case of the leather industry. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 47(1), 19–38.

- Dong, X., Li, H., Liu, S., Cai, C., & Fan, X. (2018). How does material possession love influence sustainable consumption behavior towards the durable products? Journal of Cleaner Production, 198, 389–400.

- Emerich, M. (2012). The Gospel of sustainability: Media, market, and LOHAS. Contemporary Sociology: A Journal of Reviews, 41(4), 532–532.

- Fiore, M., Silvestri, R., Contò, F., & Pellegrini, G. (2017). Understanding the relationship between green approach and marketing innovations tools in the wine sector. Journal of Cleaner Production, 142, 4085–4091.

- Gaur, J., Amini, M., Banerjee, P., & Gupta, R. (2015). Drivers of consumer purchase intentions for remanufactured products a study of Indian consumers relocated to the USA. Qualitative Market Research, 18(1), 30–47.

- Gaur, J., Mani, V., Banerjee, P., Amini, M., & Gupta, R. (2018). Towards building circular economy. Management Decision, 57(4), 886–903.

- Ghazali, E., Soon, P. C., Mutum, D. S., & Nguyen, B. (2017). Health and cosmetics: Investigating consumers’ values for buying organic personal care products. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 39(March), 154–163.

- Godart, F., & Seong, S. (2015). Is sustainable luxury fashion possible? In Sustainable Luxury: Managing Social and Environmental Performance in Iconic Brands (pp. 11–27). Routledge.

- Grönman, K., Soukka, R., Järvi-Kääriäinen, T., Katajajuuri, J. M., Kuisma, M., Koivupuro, H. K., Ollila, M., Pitkänen, M., Miettinen, O., Silvenius, F., Thun, R., Wessman, H., & Linnanen, L. (2013). Framework for sustainable food packaging design. Packaging Technology and Science, 26(4), 187–200.

- Han, H., Lee, M. J., Chua, B. L., & Kim, W. (2019). Triggers of traveler willingness to use and recommend eco-friendly airplanes. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 38(July 2018), 91–101.

- Hsu, C. L., Chang, C. Y., & Yansritakul, C. (2017). Exploring purchase intention of green skincare products using the theory of planned behavior: Testing the moderating effects of country of origin and price sensitivity. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 34(August 2016), 145–152.

- Iran, S., Geiger, S. M., & Schrader, U. (2019). Collaborative fashion consumption – A cross-cultural study between Tehran and Berlin. Journal of Cleaner Production, 212, 313–323.

- Joergens, C. (2006). Ethical fashion: Myth or future trend? Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 10(3), 360–371.

- Jung, H. J., Kim, H. J., & Oh, K. W. (2016). Green leather for ethical consumers in China and Korea: Facilitating ethical consumption with value–belief–attitude logic. Journal of Business Ethics, 135(3), 483–502.

- Jung, S., & Jin, B. (2016). From quantity to quality: Understanding slow fashion consumers for sustainability and consumer education. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 40(4), 410–421.

- Kahraman, A., & Kazançoğlu, İ. (2019). Understanding consumers’ purchase intentions toward natural-claimed products: A qualitative research in personal care products. Business Strategy and the Environment, (March), 1–16.

- Kay, T. (1994). Reiner Pilz. Salvo Monthly, 23. http://www.nrutech.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/1994_Salvo_Reiner_Pilz_Upcycling.pdf

- Kessous, A., & Valette-Florence, P. (2019). “From Prada to Nada”: Consumers and their luxury products: A contrast between second-hand and first-hand luxury products. Journal of Business Research, 102, 313-327.

- Khare, A., & Varshneya, G. (2017). Antecedents to organic cotton clothing purchase behaviour: Study on Indian youth. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 21(1), 51–69.

- Kim, H. J., Kim, J. Y., Oh, K. W., & Jung, H. J. (2016). Adoption of eco-friendly faux leather: Examining consumer attitude with the value–belief–norm framework. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 34(4), 239–256.

- Lee, H., & Cheon, H. (2018). Exploring korean consumers’ attitudes toward ethical consumption behavior in the light of affect and cognition. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 30(2), 98–114.

- Liang, J., & Xu, Y. (2018). Second-hand clothing consumption: A generational cohort analysis of the Chinese market. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 42(1), 120–130.

- Magnier, L., Mugge, R., & Schoormans, J. (2019). Turning ocean garbage into products – Consumers’ evaluations of products made of recycled ocean plastic. Journal of Cleaner Production, 215, 84–98.

- Matthews, D., & Rothenberg, L. (2017). An assessment of organic apparel, environmental beliefs and consumer preferences via fashion innovativeness. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 41(5), 526–533.

- McNeill, L., & Venter, B. (2019). Identity, self-concept and young women’s engagement with collaborative, sustainable fashion consumption models. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 43(4), 368-378.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Open Medicine : A Peer-Reviewed, Independent, Open-Access Journal, 3(3), e123-30.

- Moraes, C., Carrigan, M., Bosangit, C., Ferreira, C., & McGrath, M. (2017). Understanding ethical luxury consumption through practice theories: A study of fine jewellery purchases. Journal of Business Ethics, 145(3), 525–543.

- Muthu, S. (2016). Textiles and Clothing Sustainability: Recycled and Upcycled Textiles and Fashion. Springer.

- Nash, J., Ginger, C., & Cartier, L. (2016). The sustainable luxury contradiction: Evidence from a consumer study of marine-cultured pearl jewellery. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 2016(63), 73–95.

- Ndichu, E. G., & Upadhyaya, S. (2019). “Going natural”: Black women’s identity project shifts in hair care practices. Consumption Markets and Culture, 22(1), 44–67.

- Norum, P., & Norton, M. (2017). Factors affecting consumer acquisition of secondhand clothing in the USA. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 21(2), 206–218.

- Onel, N., Mukherjee, A., Kreidler, N. B., Díaz, E. M., Furchheim, P., Gupta, S., Keech, J., & Murdock, M. R., & Wang, Q. (2018). Tell me your story and I will tell you who you are: Persona perspective in sustainable consumption. Psychology and Marketing, 35(10), 752–765.

- Paparoidamis, N. G., & Tran, H. T. T. (2019). Making the world a better place by making better products: Eco-friendly consumer innovativeness and the adoption of eco-innovations. European Journal of Marketing, 53(8), 1546-1584.

- Paul, J., Modi, A., & Patel, J. (2016). Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 29, 123–134.

- Pudaruth, S., Juwaheer, T. D., & Seewoo, Y. D. (2015). Gender-based differences in understanding the purchasing patterns of eco-friendly cosmetics and beauty care products in Mauritius: A study of female customers. Social Responsibility Journal, 11(1), 179–198.

- Qutab, M. (2017). What’s the Second Most Polluting Industry? (We’ll Give You A Hint – You’re Wearing It). https://www.onegreenplanet.org/environment/clothing-industry-second-most-polluting/

- Ritch, E. L. (2015). Consumers interpreting sustainability: Moving beyond food to fashion. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 43(12), 1162–1181.

- Rolling, V., & Sadachar, A. (2018). Are sustainable luxury goods a paradox for millennials? Social Responsibility Journal, 14(4), 802–815.

- Saleem, M. A., Eagle, L., Yaseen, A., & Low, D. (2018). The power of spirituality. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 30(4), 867–888.

- Scherer, C., Emberger-Klein, A., & Menrad, K. (2018). Consumer preferences for outdoor sporting equipment made of bio-based plastics: Results of a choice-based-conjoint experiment in Germany. Journal of Cleaner Production, 203, 1085–1094.

- Shen, D., Richards, J., & Liu, F. (2013). Consumers’ awareness of sustainable fashion. Marketing Management Journal, 23(2), 134–147.

- Shin, J., Kang, S., Lee, D., & Hong, B. Il. (2018). Analysing the failure factors of eco-friendly home appliances based on a user-centered approach. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(8), 1399–1408.

- Turunen, L. L. M., & Leipämaa-Leskinen, H. (2015). Pre-loved luxury: Identifying the meaning of second hand luxury possessions. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 24(1), 57–64.

- Vehmas, K., Raudaskoski, A., Heikkilä, P., Harlin, A., & Mensonen, A. (2018). Consumer attitudes and communication in circular fashion. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 22(3), 286–300.

- Weber, S., Lynes, J., & Young, S. B. (2017). Fashion interest as a driver for consumer textile waste management: Reuse, recycle or disposal. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 41(2), 207–215.

- Wiedmann, K. P., Hennigs, N., & Siebels, A. (2009). Value-based segmentation of luxury consumption behavior. Psychology and Marketing, 26(7), 625–651.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

06 October 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-087-7

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

88

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1099

Subjects

Finance, business, innovation, entrepreneurship, sustainability, environment, green business, environmental issues

Cite this article as:

Hasbullah, N. N., Sulaiman, Z., & Mas’od, A. (2020). Systematic Literature Review Of Sustainable Fashion Consumption From 2015 To 2019. In Z. Ahmad (Ed.), Progressing Beyond and Better: Leading Businesses for a Sustainable Future, vol 88. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 341-351). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.10.30