Abstract

The article is devoted to the consideration of the problem of the features of the self-relationship of the personality of students with various levels of perfectionism. Perfectionism is studied as a multidimensional construct, characterized by various levels and types and having both positive and negative effects on the personality, its communication and its activities. The specificity of personality perfectionism during vocational training is investigated. Studentship is considered as one of the periods of professional development of the personality, where the most favorable conditions are created for the manifestation of such a personal characteristic as perfectionism, and in its various types and degrees of severity. Attention is paid to studying the severity of perfectionism by levels: low, medium, high. The levels of perfectionism are compared with its types such as self-perfectionism, perfectionism directed at others and socially prescribed perfectionism. The prevalence of the above types of perfectionism was revealed depending on its level: low, medium, high. Self-relationship profiles were compiled depending on the level of perfectionism in the subjects. The specificity of the severity of the various components of self-relationship is revealed, depending on the respondents belonging to a particular level of perfectionism. The interdependencies of the studied types of perfectionism in students with various aspects of self-relationship are revealed. The revealed connections of the integral indicator of perfectionism with such characteristics of self-attitude as self-confidence, self-leadership, reflected self-attitude, self-worth are analyzed. The specificity of self-attitude among students with a high level of perfectionism is revealed.

Keywords: Perfectionismself-attitudestudentshigh level of perfectionism

Introduction

Professional development of students is aimed at achieving the highest possible result, which surely attracts the attention of researchers of the phenomenon of perfectionism. The behavior of perfectionists is subject to the implementation of excessively high standards, combined with the tendency to supercritically evaluate their own behavior ( Yasnaya & Enikolopov, 2007). Perfectionism is also manifested in a tendency to follow an overestimated standard of activity and to put too high demands on one's self. Currently, it has been established that pathological perfectionism is directly related to maladaptation emotionally and socially. On the other hand, normal perfectionism stimulates self-development and self-improvement of the personality. This ambiguity of the subjective well-being of the individual determines the relevance of the timely detection and correction of perfectionism. Due to the need to optimize perfectionism, carriers of a high level of perfectional installations and values require increased attention to themselves.

The study of perfectionism in the student period of personality development is of particular interest due to the fact that students have a strong intention of their own development, that is, students are especially sensitive, sensitive to self-disclosure and self-improvement. The leading type of activity at the student age is educational and professional activity, therefore, this will contribute to the active manifestation of perfectionism, to varying degrees, among participants in the educational process.

Student youth lives in a situation of instability of socio-economic relations in the world, which can provoke psychological disorders. Moreover, students are exposed to systematic stressful situations during the sessions. Therefore, perfectionist students can be rationally classified as a risk group. For such students, teacher assessment situations are extreme due to their hypersensitivity to criticisms. Fixing increased attention to the desire to achieve the best indicators in educational and professional activities, perfectionist students self-incriminating for the slightest failure can enter themselves into a maladaptive mental state. The latter can manifest itself in anxiety, depression, a tendency to a nervous breakdown, and even suicide. The foregoing causes an urgent need for psychological and pedagogical support of students in the process of obtaining a vocational education.

Problem Statement

High standards imposed on the personality of a professional in the modern technological space have their origin in the period of professional training. Modern university students are, on the one hand, subject to anxiety about further employment, professional competitiveness, and, on the other hand, they need to meet the requirements of educational and professional standards at a high level. It has already become traditional to consider perfectionism a characteristic feature of modern society, which is expressed in a constant desire to meet high criteria and requirements for various social roles, in particular the role of a professional. In connection with these, perfectionist attitudes among university students who are oriented in the process of obtaining a profession towards success, achievement, and self-improvement are quite logical. Despite a large number of international studies on the problem of manifestations of perfectionism among students, the question of the relationship between perfectionism and various aspects of self-attitude among university students, as well as the features of such a relationship with a high level of perfectionism, remains understudied.

In modern psychology, perfectionism refers to the subject's desire for perfection; it is characterized by the presence of high personal standards, the need for experiencing excellence with respect to the products of one's own activity, the desire to bring the results of any activity to the highest standards ( Kononenko, 2014).

Modern researchers have decided to consider perfectionism as a multidimensional construct, taking into account both its positive and destructive effects on a person’s personality ( Zolotareva, 2013). A number of studies are devoted to the study of pathological (neurotic, narcissistic, obsessive-compulsive) perfectionism ( Kholmogorova & Garanyan, 2004; Malkina-Pykh, 2010; Sokolova, 2015; Yasnaya & Enikolopov, 2007). With the support of modern sociocultural standards of society, perfectionism, in addition to a completely healthy component, has significant clinical dependence ( Sokolova, 2015). The lines separating healthy perfectionism and pathological are distinguished by several researchers. Among them are the presence of complex, differentiated, carefully reflexive ideas about the ideal self against the background of the rejection of the real self ( Kholmogorova & Garanyan, 2004), preoccupation with mistakes and doubt in their own actions ( Malkina-Pykh, 2010), the need to avoid the failure to which perfectionists react with symptoms of depression ( Schweitzer & Hamilton, 2002) and others.

Studies of perfectionism both in Russia and abroad are carried out in relation to various groups of professionals. The study of perfectionism among students goes in the direction of clarifying mediation and its connection with various personal qualities: achievement motivation ( Putarek et al., 2019), academic difficulties and academic activity ( Cowie et al., 2018; Leanna et al., 2017), self-realization ( Belyakova et al., 2016), etc. The connections between perfectionism and self-relations among students are quite controversial and require further clarification ( Komissarova, 2012; Mironova & Dondulova, 2010; Novgorodova, 2014).

Research Questions

The subject of our study is the specificity of self-attitude among university students with a high level of perfectionism. Perfectionism can have both positive and negative manifestations, depending on its severity and orientation, respectively, can have a completely ambiguous effect on the personality, its activities and communication.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the work is to identify the characteristics of self-relations among students with various levels and prevailing types of perfectionism.

Research Methods

The study of various aspects of students' self-attitude and their level and type of perfectionism, as well as their interconnections, was carried out using psycho-diagnostics as a research method, as well as using methods of mathematical statistics. The first stage of the study was devoted to identifying the actual levels and types of perfectionism among students and, when implemented, such techniques were used as the multidimensional scale of perfectionism ( Gracheva, 2006), differential test of perfectionism ( Zolotareva, 2013). At the second stage, various aspects of self-relation were studied that were most typical for the subjects (the method of studying self-relation (Stolin, 2003). At the third stage, using the methods of mathematical statistics (Kruskal Wallis H-test, Pearson correlation criterion), the presence of the desired differences and correlations.

Findings

The results obtained on the multivariate Hewitt perfectionism scale are presented in Tables

Most of the test students (64 %) are characterized by a high level of perfectionism. A low level of perfectionism is inherent in the smallest number of students (14 %). Table

Thus, with a low level of perfectionism (on an integrated scale), the socially prescribed type of perfectionism (56.3) and perfectionism oriented to others (53.2) prevail. Respondents with an average level of perfectionism (on an integrated scale) are characterized by pronounced self-oriented perfectionism (100.9). Such students are more likely to make extremely high demands on themselves. With a high level of perfectionism (on an integrated scale), high levels of perfectionism oriented towards others (98.6) and socially prescribed perfectionism (81.0) prevail. Students with a high level of perfectionism tend to make extremely high demands on others, and the demands that others make on them are regarded as overvalued and unrealistic.

To determine the significance of differences in the types of perfectionism at different levels of severity of the integral scale of perfectionism according to the multivariate Hewitt-Flett perfectionism scale, the Kruskall-Wallis H-test was used. Significant differences between the three types of perfectionism studied are identified, which are distributed across the levels of integral perfectionism. So, on the scale of “self-oriented perfectionism”, students with low, medium and high levels of perfectionism on the integrated scale are significantly different from each other (Hemp = 200.6, ρ > 0.01). According to the scale “perfectionism oriented to others”, students with a low, medium and high level of perfectionism on the integral scale significantly differ from each other (Hemp = 202.8, ρ > 0.01). On the scale of “socially prescribed perfectionism”, students with low, medium and high levels of perfectionism on the integrated scale are significantly different from each other (Hemp = 201.5, ρ > 0.01). And also, on “perfectionism integral scale”, students with low, medium and high levels of perfectionism on the integral scale are significantly different from each other (Hemp = 200.6, ρ > 0.01).

The results of the differential test of perfectionism, which allows identifying the existing level of normal or pathological perfectionism ( Zolotareva, 2013), are compared with the previously identified levels of the scale of integral perfectionism (Table

With a low level of perfectionism (on an integrated scale), normal perfectionism is expressed (100 %). With an average level of perfectionism (on the integrated scale), normal perfectionism prevails (80 %), one fifth of students have pathological perfectionism (20 %). With a high level of perfectionism (on an integrated scale), normal perfectionism prevails (69 %), one third of students have pathological perfectionism (31 %).

The reliability of differences between normal and pathological perfectionism according to the method of Zolotareva ( 2013) at different levels of severity of the integral scale of perfectionism was revealed using the Kruskall-Wallis H-criterion (Table

Thus, students with a low, medium and high level of perfectionism reliably differ from each other in terms of the severity of types of perfectionism identified by the method of Zolotareva ( 2013) (ρ > 0.05).

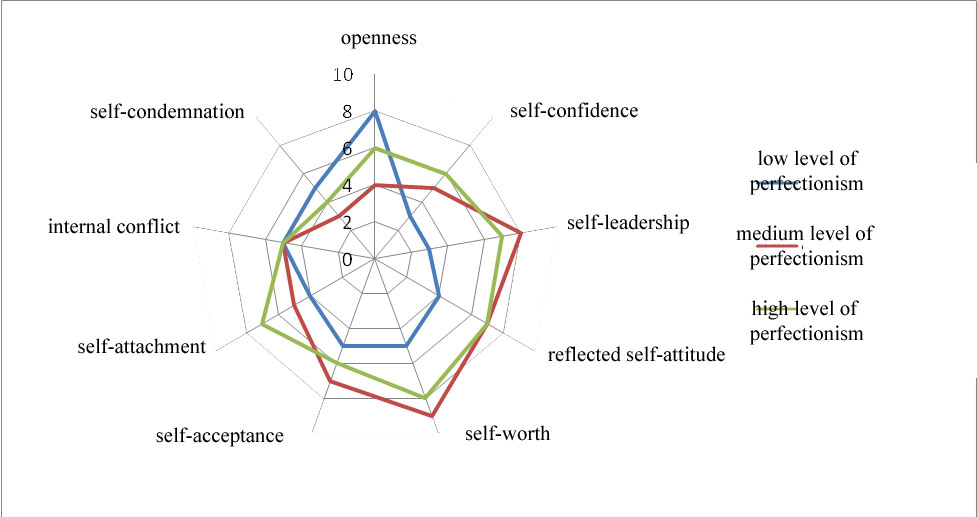

The results of the study of self-relation in comparison with the integral levels of perfectionism in students are presented in Figure

The self-relationship profile with a low level of perfectionism is characterized by a high level of openness (8.5); the medium level of severity of the parameters of self-attitude: reflected self-attitude (2.9), self-worth (7.2), self-acceptance (7.2), self-attachment (3.2), internal conflict (6.2), self-condemnation (4.2); low level of self-attitude parameters: self-confidence (2.6) and self-leadership (2.8). The profile of self-relationship with an medium level of perfectionism reflects a high level of the parameters of self-attitude: self-leadership (8.7) and self-worth (12.2); the medium level of severity of self-attitude parameters: openness (1.6), self-confidence (9.3), reflected self-attitude (8), self-acceptance (8.9), self-attachment (4.4), internal conflict (7.2); low level of self-condemnation parameters (2.3). The profile of self-relationship with a high level of perfectionism reflects a high level of expression of self-worth (10.9); the medium level of self-attitude parameters: openness (5.7), self-confidence (10.3), self-leadership (7.5), reflected self-attitude (8.2), self-acceptance (7.9), self-attachment (8.1), internal conflict (6.1), self-condemnation (3.9).

Thus, with a low level of perfectionism openness prevails, self-confidence and self-leadership are weakly expressed. At a medium level of perfectionism, self-worth and self-leadership are pronounced, self-condemnation is weakly expressed. With a high level of perfectionism, the self-worth of the personality is clearly expressed, in the absence of weakly expressed features.

The significance of differences in the severity of the parameters of self-attitude at different levels of severity of the integral scale of perfectionism was revealed using the Kruskall-Wallis H-test (Table

Thus, students with a low, medium and high levels of perfectionism significantly differ from each other in terms of the severity of self-attitude parameters: openness (ρ> 0.05), self-confidence (ρ> 0.01), self-leadership (ρ> 0.01), reflected self-attitude (ρ> 0.05), self-worth (ρ> 0.05), self-attachment (ρ> 0.05).

To identify the relationships between the studied parameters of perfectionism and self-relationship, we used the linear correlation Pearson coefficient r. The results of significant correlations between are presented in Table

The most significant correlations relate to the relationship between integral perfectionism and the self-leadership scale (0.442), as well as such types of perfectionism as self-oriented perfectionism, others-oriented perfectionism, and socially prescribed perfectionism with some self-attitude scales. So, self-oriented perfectionism is closely related to self-attitude parameters such as self-leadership (0.425) and self-worth (0.373), while others-oriented perfectionism correlates with self-confidence (0.464) and self-attachment (0.652). Socially prescribed perfectionism found a close relationship with such an indicator of self-relation as reflected self-attitude (0.357).

Conclusion

-

Students of the studied sample are more characterized by a high level of perfectionism, but which is within the normal range. This is the so-called normal perfectionism, where the subject has a number of positive qualities that contribute to his successful activity and quite satisfactory functioning in the social world, as well as leading to the experience of his own value and confidence. The most expressed is the orientation of perfectionism as that directed at others and socially prescribed perfectionism, the latter being attributed by a number of researchers to neurotic, maladaptive ( Malkina-Pykh, 2010). Students of this sample are more characteristic of experiencing an external, social source of high requirements, as well as the presence of higher requirements for others than for themselves. Part of the students in the group of medium and high levels of perfectionism is also inherent in pathological perfectionism. That is, students of medium and high level of perfectionism, relatively speaking, represent a certain risk group for the development of psychopathologies.

-

The features of self-attitude in students with various levels of perfectionism are determined. Students with a high level of perfectionism are characterized by a fairly stable, overly-positive self-image, with a low degree of openness to the world, as well as the presence of a rigid image of the self, which has quite rigid features. Such students are inclined to develop such protective mechanisms that contribute to the sustainability of a highly positive self-image. Such students are also fully confident that others approve and support their actions. For comparison, students with a low level of perfectionism have a high degree of credulity and openness, but they are much less confident in themselves. Also, the so-called inner core, reliance on the Self is not sufficiently developed in them. Students with an average level of perfectionism have a more harmonious structure of self-relationship. Here, with a sufficiently high level of a positive attitude towards oneself and a locus of control of the Self, there is a sufficient degree of acceptance of oneself with all its merits and mistakes.

-

The revealed correlation dependencies between the studied parameters also serve as evidence of the presence of self-relational features in students with various levels of perfectionism. Students who make high demands on themselves are primarily characterized by experiencing their own inner strength and worth, a positive attitude towards themselves and their own actions, and confidence that their own lives and their own feelings are under personal control. In the event that perfectionism is more oriented toward others, the subject himself is characterized by a tendency to a high degree of strong-willed self-confidence and that people around him also perceive it in a rather rigid way, a weak ability to self-change. The connection obtained between socially prescribed perfectionism as experiencing a source of high requirements located outside and the tendency to increase the expectation of all kinds of social recognition and a positive attitude towards oneself is quite natural.

References

- Belyakova, N.V., Petrova, E.A., Romanova, A.V., & Akimova, N.N. (2016). Formation of professional self-realization of student athletes at the stage of leaving sports of the highest achievements. Theory and pract. of phys. Ed. and sports, 3, 32–34.

- Gracheva, I. I. (2006). Adaptation of the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale methodology by P. Hewitt and G. Flett. Psycholog. J., 6, 73–81.

- Kholmogorova, A.B., & Garanyan, N.G. (2004). Narcissism, perfectionism and depression. Moscow Psychotherap. J., 1, 18–35.

- Komissarova, L.G. (2012). Peculiarities of the self-relationship of students with self-oriented perfectionism. Bull. of the Buryat State Univer., 5, 46–51.

- Kononenko, O.I. (2014). Theoretical models for the study of personality perfectionism in foreign psychology. Rem: Psychol. Educol. Med., 1, 49–57. Retrieved from: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/v/teoreticheskie-modeli-izucheniya-perfektsionizma-lichnosti-v-zarubezhnoy-psihologii

- Leanna, M., & Closson, R. R. (2017). Boutilier Perfectionism, academic engagement, and procrastination among undergraduates: The moderating role of honors student status. Learn. and Individual Differences, 57, 157–162. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.04.010.

- Malkina-Pykh, I.G. (2010). Research on the relationship of self-actualization and perfectionism in the structure of personality. World of psychol., 1, 208–218.

- Cowie, M. E., Nealis, L. J., Sherry, S. B., Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (2018) Perfectionism and academic difficulties in graduate students: Testing incremental prediction and gender moderation. Personality and Individual Differences.123, 223–228. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.11.027

- Mironova, T.L., & Dondulova, E.V. (2010). Features of the self-attitude of students prone to perfectionism. Bull. of the Buryat Univer., 5, 88–100.

- Novgorodova, E.F. (2014). The relationship of manifestations of perfectionism and self-identity. Letters of emission: Electron. Sci. J., 10, 2263.

- Putarek, V., Rovan, D., & Pavlin-Bernardić, N. (2019). Relations of patterns of perfectionism to BIS sensitivity, achievement goals and student engagement. Learn. and Motivat., 68. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lmot.2019.101596

- Schweitzer, R, & Hamilton, T. (2002). Perfectionism and mental health in Australian university students: is there a relationship. J. College Stud. Dev., 43(5), 684–695.

- Sokolova, E.T. (2015). Clinical psychology of loss of Self. Moscow: Smysl.

- Stolin, V.V. (2003). Personal identity. Moscow: Moscow State Univer.

- Yasnaya, V.A., & Enikolopov, S.N. (2007). Perfectionism: a history of study and the current state of the problem. Quest. of Psychol., 4, 157–168.

- Zolotareva, A.A. (2013) Differential diagnosis of perfectionism. Psycholog. J., 34 2), 117–128.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 October 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-091-4

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

92

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-3929

Subjects

Sociolinguistics, linguistics, semantics, discourse analysis, translation, interpretation

Cite this article as:

Berber, N., Belyakova, N., & Romanova, A. (2020). Features Of The Self-Attitude Of Students With A High Level Of Perfectionism. In D. K. Bataev (Ed.), Social and Cultural Transformations in the Context of Modern Globalism» Dedicated to the 80th Anniversary of Turkayev Hassan Vakhitovich, vol 92. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1467-1475). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.10.05.193