Abstract

The paper analyzes images of the Orthodox sculpture and icon paintings from the collections of Perm State Art Gallery, Tobolsk Historical and Architectural Museum-Sanctuaries, Irkutsk Regional Art Museum. Among the objects analyzed, the authors' attention was drawn to images of the Ural-Siberian origin of the XVII-XIX centuries with a pronounced anthropological appearance of the Finno-Ugric (mainly Komi-Permyak and Ob-Ugric) and the Tatar populations; as comparison the paper describes the Byzantine icons of an earlier origin with the anthropological appearance of other peoples. The “ethnic” approach to images was practiced in the history of the church with a missionary purpose to create an image of Orthodoxy that would be closer to the local environment, including the existing beliefs. The authors noted that the anthropological appearance on the icons is often accompanied by the colors of those religions to which the flock subjected to missionary belonged: green – in the case of Islam, orange – in the practice of Buddhism, etc. The paper notes that this approach was used by the Orthodox Church in different historical periods, but it appeared first in Byzantium and was transferred to the iconography of the Urals and Siberia. This emphasizes the continuity of the Orthodox culture, its religious canons and the principles of images preserved in different political conditions. At that time it was the source of anthropological appearance and the religion of peoples who fell into the missionary activity of the Christian Church.

Keywords: Orthodox artIslamFinno-Ugric peoplesUralsSiberiaByzantium

Introduction

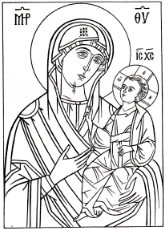

In September 2019, part of the European parishes belonging to the Russian tradition came under the jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Church. This means that the general canons were adopted, in the history of which there were some stories that became the subject for scientific debates. In addition to the Arabic graphics used in the church texts, the Turkish-Muslim ornaments on the clothes of priests, and other discussion-based artifacts, there were some icons and the Orthodox sculptures with uncharacteristic images of the local ethnic environment for Orthodoxy, including non-European anthropological features of Jesus Christ and Saints, colors of other religions and local technology at manifacturing some objects of worship. The study of these samples gives us the possibility to supplement the history of people living under the influence of the Orthodox missionaries (Figure

Problem Statement

Some Orthodox iconographic and sculptural images of the Ural-Siberian origin have a pronounced Mongol-Tatar or Finno-Ugric anthropological appearance, which indicates the ethnic composition of the flock. The largest number of such items was created by the dioceses in the XVII–XVIII centuries, gradually decreasing in the XIX century. In the Vatican Pinakothek’s funds, similar “ethnic” patterns were created in different centuries, but most of them belong to the XIII–XIV centuries, which is 400 years earlier. In the Ural-Siberian region, the use of Byzantine visual principles through such an impressive period should have serious reasons: a mere imitation to the country traditions which has not existed for 200 years seems to be a rather insufficient explanation. Therefore, the issue requires a more detailed analysis.

Research Questions

The anthropological appearance of the mages in the Orthodox icons of the Urals and Western Siberia, as well as the images and colors of other religions, have not yet become the subject of a scientific independent study. In the framework of some scientific works, this phenomenon was described though without the link with the missionaries’ practice and Byzantium traditions (Levchenko & Yarkov, 2016; Lobzova, 2018). The main part of the works is devoted directly to the Ural and Siberian icon painting, mainly to the Stroganov and Nevyansk paintings, including the traditions of the Old Believers (Prokhorova, 2012; Rusanov, 2008; Trofimova, 2010). The issues on how the images of the local ethnic environment were used have been reflected in previous works of the authors on the Orthodox sculpture of the XVII century. The sample were taken from the funds of the Perm State Art Gallery and the Tobolsk Historical and Architectural Museum-Sanctuaries, intended for missionary work among the Finno-Ugric population, as well as the culture of the Siberian Tatars-Kryashen and traditions of the syncretic version of Siberian Islam (Bortnikova et al., 2016; Naumenko et al., 2016). Another group of studies relates to the conditions of the northern regions in which cultural borrowings took place, but the issues of the Orthodox icon painting were not addressed there (Bogomolova et al., 2017; Tkachev et al., 2018). Foreign (inter alia Italian) experts, studying some religious art (Carandini, 2016; Daverio, 2018; Ravasi, 2014; Vatican, 2008, 2011) did not set a goal to project paintings from the Vatican Museums on the Ural icon painting and Siberia. In general, the scientific problem reflected in the paper has not yet been developed in modern historiography.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the paper is to trace the relationship between the Byzantine tradition and the iconography of the Urals and Siberia relating to the use of images of the local ethnic environment.

Research Methods

The methodological basis of the study is Frontier Theory (Turner, 1962). Any frontier has a regional specificity associated with the cultural landscape of the region and its natural and climatic features. In particular, Kerner (1973) investigated the role of the rivers of the Urals and Western Siberia: they were the transport arteries along which religious missionaries originally moved, therefore the greatest manifestation of religious syncretism is observed among peoples living along the banks of large rivers. The paper uses the

Findings

To study the anthropological appearance of the images, 100 samples of the Orthodox sculpture and icon painting of the XVII-XIX centuries were taken from the home exhibition of the Perm State Art Gallery, the Berezniki Museum of Local Land of the Perm Region and the Tobolsk Historical and Architectural Museum-Sanctuaries of the Tyumen Region. The result of the study showed that 77 exhibits (77 %) have characteristic Komi-Permian faces, 7 copies (7%) – Tatar faces, and the remaining 16 (16 %) reflect a Slavic / European (even Greek) appearance. The number of sculptures with Tatar faces in the collection of the Perm State Art Gallery, in all likelihood, is lower than the real-life numbers: there were more, but not all were in museums. According to the testimony of the initiator of this collection, to N.N. Serebrennikov, the numerous sculptures with Tatars’ faces were among the first in the collection; they were discovered in the 1920s. in the villages of Ilyinsky and Dmitrovsky, where, according to local sources, the Nogai Tatars lived. Later, the sculptures with ethnic faces (not only Komi Permyaks but also Tatar) were found in the villages of Verkhnekamye – Pyskor, Usolye, Redikor, Wilgort, Tsidve, Yanidor, and others, where Komi Permyaks, Khanty, Mansi lived (Serebryanikov, 1967) and, inter alia, the Tartars, judging by the sculptural images. Why in the places of the Finno-Ugric peoples’ residence there were so many Orthodox sculptures with Tatars’ (Mongol-Tatar) faces, to date this question remains not entirely clear, but as a version, it can be assumed that Turkic people may have had some pre-Christian Ugric idols.

In general, the use of the anthropological appearance of the flock was used not only on religious sculpture but also on the icons of different regions, gaining a foothold in some iconographic traces (e.g. Figure

Let us turn to St. Peter by P. Lorincetti. The image has an Indian type of face, dark skin, hair characteristic of Hindu hermits and a tunic of the orange-pink color of Buddhism. His halo is in the form of a mandorla (almond-shaped light. In the Medieval Christian painting, the mandorla was understood as a symbol of the Immaculate Conception and was depicted around the faces of Our Lady and Jesus Christ. However, in the analyzed icon, the mandorla was used for the image of the saint, and this is not characteristic to Orthodoxy. Meanwhile, the almond-shaped halo is widely known in South-east Asia. It repeats the architectural forms of religious and residential buildings, fragments of ornamental murals and other elements of local culture. Such forms of halos, as well as the attire (tunics) of the color of Buddhism, were used in Siberia on the icons of local origin for the Christianization of Lamaists (one of the directions of Buddhism). Similar icons of the XVII-XVIII centuries, with a Buryat anthropological type, have been preserved in the collections of the Irkutsk Regional Art Museum (e.g. Figure

The continuity of the art techniques is obvious, but the question is why such borrowings happened 400 years later after the Byzantine images had appeared. The reasons must be sought in a religious-political situation, similar to Byzantium that folded in the Ural-Siberian region: in the XVII–XVIII centuries there appeared the possibility to intensify missionary activity in terms of Siberia annexation to Russia, and the experience of Byzantium of the XIII–XIV centuries played a positive role. One or two centuries before the fall of the Empire in 1453, the Byzantine missionaries were active in different parts of the world. Its success was not so well spread and accepted, for instance, the Orthodoxy was not consolidated in India, and the Ottoman Empire remained Muslim. Approximately the same result was obtained in the Ural-Siberian region: in local Shamanistic, Buddhist and Muslim cultures, only traces of the Christianity influence are observed, without serious penetration into the confessions concepts.

Conclusion

The tendency revealed during the analysis of the sources shows that the images of the local ethnic environment, including the anthropological appearance and the color of the religions of the Christianized flock, were consciously used by the Orthodox icon painters to create a visual image of the Orthodoxy that would correspond to traditional culture, if possible, and the roots of this phenomenon come from Byzantium. Icon painters based on the characteristics of personality psychology associated with the perception of colors, shapes, and images, and tried to maximize the potential of the local ethnic environment. In general, the considered examples of the Orthodox art are a valuable source in the history of peoples who fell under the missionary activity of priests: icons can be used to determine not only the appearance of the people and their confession but also the degree of their religiosity and the level of knowledge of their faith.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Presidential Grant No. MK-3655.2019.6.

References

- Bogomolova, L. L., Takmashеva, I. V., Araslanov, R. K., & Zelinskaya, A. B. (2017). Priority guidelines in the socio-economic development of the northern oil and gas regions of Russia. Acad. of Strat. Manag. J., 16, Specialissue 1, 1–9.

- Bortnikova, Y. A., Naumenko, O. N., & Naumenko, E. E. (2016). Russia and Islam: State policy on formation of tolerance of Muslims in Western Siberia (1773–1917). Bylye Gody, 39(1), 14–21.

- Carandini, A. (2016). Angoli di Roma. Guida inconsuenta alla cita` antica. Editory Laterza.

- Daverio, F. (2018). Le stanze dell' armonia. Nei musei dove I' Europa era gia` unita. Rizzoli Vintage.

- Gusakova, V. O. (2006). Dictionary of the Russian religious art. Avrora.

- Kerner, R.J. (1973). The urge to the sea. The course of Russian History. The role of rivers, portages, ostrogs, monasteries and furs. Berkeley.

- Levchenko, А. M., & Yarkov, А. P. (2016). Abalakskay icon in the culture of Siberia. Bull. of Tyumen State Univer., 2(1), 138–154.

- Lobzova, О. N. (2018). Notes on portable iconostases found in the Omsk region. Bull. of Omsk Orthodox Theolog. Seminary, 2(5), 244–249.

- Naumenko, O. N., Naumenko, E. A., & Bortnikova, Ju. А. (2016). Multiculturalism of Tatar-Christians in Western Siberia as a result of confessional policy in the Russian Empire. Bylye Gody, 3, 41, 594–599.

- Prokhorova, Т. V. (2012). Orthodox traditions of the Russian North in icon painting of Siberia. Reg. architect. School, 1, 202–208.

- Ravasi, G. (2014). Le meraviglie dei Musei Vaticani. Musei Vaticani.

- Rusanov, Ya.A. (2008). South-Ural monuments of Old Beliver icon paining of the late XIX and the beginning of ХХ centuries (based on private collection of O. Kalmin). Bull. of South-Ural State Univer., 6(106), 79–84.

- Sacks, O. (1997). L' isola dei senza colore e l' isola delle cicadine. GLI ADELFI.

- Serebryanikov, N.N. (1967). Perm wooden sculpture. Perm.

- Tkachev, B., Fedulov, I., Moldanova, T., & Tkacheva, T. (2018). Everyday Ethnocultural Adaptation of Newly Arrived and Indigenous Populations in Yugra. SHS Web of Conf. 2018. 50. 01184. https://www.shs-conferences.org/articles/shsconf/pdf/2018/11/shsconf_ cildiah2018_01184.pdf

- Trofimova, N. V. (2010). Concept of “Nevyansk school of icon painting” in the Russian historiography. Bull. of South-Ural State Univer., 8(184), 76–79.

- Turner, F. (1962). The Frontier in American History. New York.

- Vatican (2008). Guida ai capovalovari della Pinoneka Vaticana. SCALA.

- Vatican (2011). I Musei Vaticani. Conossere, la storia, le opera, le collesione. Edizione Musei Vaticavi.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 October 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-091-4

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

92

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-3929

Subjects

Sociolinguistics, linguistics, semantics, discourse analysis, translation, interpretation

Cite this article as:

Naumenko, O., Bortnikova, J., & Evgeny, N. (2020). Ethnic Environment Images Reflection In The Orthodox Art Of Xiv-Xix Centuries. In D. K. Bataev (Ed.), Social and Cultural Transformations in the Context of Modern Globalism» Dedicated to the 80th Anniversary of Turkayev Hassan Vakhitovich, vol 92. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 784-790). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.10.05.105