Abstract

Marginalized populations such as sex workers are at constant risk of violence, abuse, and human rights violation due to inadequate laws governing their rights. Although media has an integral role in influencing the public’s perception of these vulnerable populations, it continues to reinforce social stigmas and discrimination against sex workers through stereotypical and negative representation of the populations. Drawing on Wodak’s discourse-historical approach (DHA), this paper is an outcome of a study that used the DHA analytical tools to examine the discursive strategies specifically

Keywords: Discourse-historical approachsex workersstigmanews mediadiscursive strategies

Introduction

Traditional sexual morality in many cultures, views sex as acceptable only within marriage, and the access to women’s bodies are reserved for only one man (Primoratz, 1999). Hence, when viewed through the lens of sexual ethics, commercial sex is considered morally flawed and 'deviant.' In the attempt to remove this deviant act, the sex industry and sex workers have received different types of sanctions, formally in the policy and legal codes that criminalize solicitation of sex, and socially through discrimination and stigmas against the sex trade and the workers. According to Foucault, (1978), the policing of sex began in the 17th century when tighter controls were placed on any form of sexual discourse. Through this control, a religious confession known as 'Christian Pastoral' was established where Christians were obligated to disclose their sexual misconduct, sexual desires, fantasies, thoughts, and any sexual inclinations to the church. This practice was a turning point when sex became a public matter, and subsequently policed and administered by the ruling authority.

Sex Industry in Malaysia

In Malaysia, sex workers were first cited in The Story of Abdullah, the first commercial Malay literary text published in 1849 (as cited in Nagaraj & Yahya, 1995). In the book, Abdullah recounted his observation of sex workers that he described as 'loose women.' However, the sex industry in Malaysia is believed to have emerged as early as 1718. Purcell (1948) suggested that the emergence of brothels in 1718 in Peninsular Malaysia was due to the gender imbalance of migrant workers brought in by the British to work in the mines and plantations. It was recorded that between 1839 and 1880s, the ratio of males against female migrants in Peninsular Malaysia was at 18 to 1000, and this increased demand for sex workers.

In 1870, the first policy that regulates brothels, known as Contagious Diseases Ordinance, was introduced as an attempt to contain the outbreak of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Although the policy was primarily established to control STDs, the compulsory medical examination imposed on brothels had benefited sex workers and protected them from enforced detention and ill-treatment (Warren, 1994). However, the ruling was repealed in 1888, and with that, the medical inspection required for the workers was also withdrawn. In 1931, a new regulation was drafted, and brothels were illegalized entirely, resulting in the criminalization of the industry as well as the people working in the sector (Lim, 1998; Warren, 1994). At present, although prostitution is not a criminal offense under the Malaysian Federal Law, the exploitation of women for prostitution is an offense punishable by imprisonment and a fine or both. This regulation is enacted in the Penal Code 574 Sections 327a and 327b (Penal Code Act 574, 2015). In addition to this provision, sex work is also regulated under the Syariah law, Act 559, Section 21 (Syariah Criminal Offences Act 1997, 2002). Syariah law is another body of jurisdiction that governs Muslims in Malaysia. Under this provision, sex work is considered as an offense relating to decency, and sanction can include imprisonment and a fine or both.

Problem Statement

When Malaysia was listed on Tier 2 of the U.S. Department of State's Trafficking in Persons 2011 Report, the Malaysian government established the Anti-Trafficking in Persons and Anti-Smuggling of Migrants (the ATIPSOM) under the Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act 2007. This newly merged law considers trafficked persons living on or receiving the profits of prostitution, including victims of trafficking as illegal migrants (Human Rights Commission of Malaysia, 2010). The inclusion of trafficked victims under this law was highly criticized as it undermines the need to identify and safeguard sex trafficking victims. Besides the ambiguity in the law enforcement, the media plays a significant role in influencing public attitudes towards this population. Much research has shown the mounting evidence of stigmatization of sex workers perpetuated in the media where they are depicted as the ‘other’ and ‘deviant’ even when their involvement is forced (Hallgrímsdóttir et al., 2008). Research has also shown that sex workers often refuse to seek legal protection when faced with violence or ill-treatment since, in many cases, the perpetrators are reported to be people from the law enforcement itself (Gould & Fick, 2008; Scorgie et al., 2013; SWEAT, 2013). As a result, sex workers often regard the assaults against them as normal and as part of their line of work (Hallgrímsdóttir et al., 2008; Svinurai et al., 2019).

Adding to this, academic research on sex workers is also scarce, and they are often interlaced with topics that are frequently linked with sex workers, for instance, the research on AIDS, HIV, and human trafficking (Kantola & Squires, 2004; Noor, 2015). As such, this study is significant as it fills in the gap that exists in the research on sex workers in Malaysia by exploring the discursive representation of this population as the negative-other found in the Malaysian news media. This study believes that the way sex workers are depicted as the negative-other in the media, if not exposed, will continue to perpetuate sex workers’ stigmatization and hinder their rights for public benefits such as health care services, legal rights, and protection from violence and human rights violations.

Research Questions

This study used Wodak’s (2001) Discourse Historical Approach (DHA) in Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), and research questions for this study were formulated based on the strategies suggested in DHA. The research questions that guide this study are:

What are the linguistic items used to name and refer to sex workers in the news media?

What are the characteristics and qualities attributed to these workers?

What arguments used to rationalize the negative representations of these workers?

Purpose of the Study

The main purpose of this study is to investigate the explicit and implicit discursive strategies employed in the mainstream media in Malaysia in their representation of sex workers as the negative-other. Through this investigation, the study aims to reveal how sex workers are depicted negatively and how these depictions are justified and legitimized in the media. With this revelation, it will show the extent that negative portrayals of sex workers in the news media contribute to shape and reinforce stigma and discrimination against the population. To achieve this objective, this research attempts:

To examine the ways in which sex workers are negatively represented in the mainstream news media in Malaysia

To examine the argumentative strategies employed by the media to legitimize their representations of sex workers.

Research Methods

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) considers the language used to represent a particular group of people within media texts; for example, sex workers as ideological. In other words, the linguistic items assigned to sex workers by and in the media are central to shape and reinforce the way in which the wider public views and treats the sex workers’ population. Using the Discourse Historical Approach (DHA) in CDA, this research aims to identify the way sex workers are negatively represented in the Malaysian news media. DHA is chosen for a number of reasons, firstly due to its concerns on historical contexts and secondly, its interdisciplinary nature in which it considers perspectives from different fields of studies as well as triangulates its methods of data collection and analysis. As such, DHA provides a number of advantages, including minimizing the risk of biases by capturing the topic under study from different angles, and the triangulation of data from multiple sources to ensure a comprehensive and complete examination of the discursive event (Reisigl & Wodak, 2017).

The Construction of Negative-Other

In the DHA, the construction of the negative-other is a discursive practice frequently used to discredit a particular group of people as

The Discursive Strategies

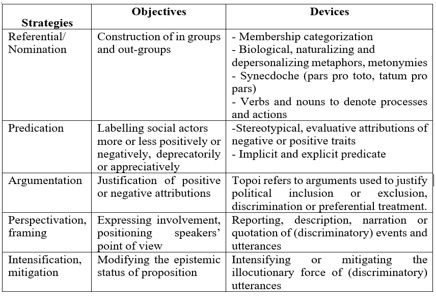

To examine the explicit and implicit strategies in the construction of the negative-other, Reisigl and Wodak (2017) propose the discursive strategies as tabled in Figure

Drawing from the five-discursive strategies in Figure

Data Collection

The data for this study consists of 20 news reports relevant to sex workers in Malaysia circulated in

Findings

In all the twenty news articles, the findings revealed that sex workers were consistently represented as the negative-other and limitedly, as offenders and as victims in

Collectivized and Aggregated

Throughout the news reports, while sex workers were frequently collectivized as a group using plural nouns such as ‘

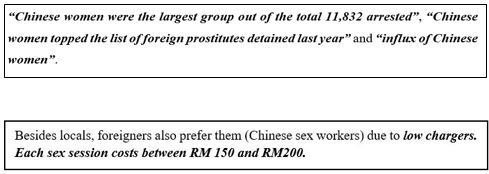

The specific mention of sex workers from China as seen in Figure

The use of numerative was also frequent when these workers were portrayed as criminals. The implication of aggregating a particular group of people and representing them as statistics, polls, surveys, or numbers is that it helps to create the group as a distanced population. Consequently, the group’s projection as a specimen instead of a person will reduce the readers’ empathy towards the population, making any actions taken against them deemed justifiable. Additionally, aggregation can also be interpreted as the public's consensus, which works the same way as to how statistics, polls, and surveys are used in the governmental organizations or the marketing as a mechanism to manufacture consensus opinion. By representing sex workers in the form of statistics, these workers are not only objectified to numbers, but the statistics present their criminalization as facts agreed by the public. However, this representation is in a stark difference with the workers’ narration as victims. As victims, the workers’ age was frequently highlighted. They were identified as very young women and, as such, helpless, innocent, and in need of saving.

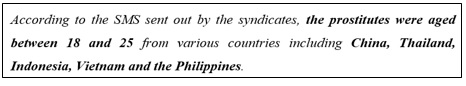

In the excerpt (see Figure

Activated and Passivated

As analysed above, even though sex workers were impersonalized, their involvement in the sex trade was frequently depicted as purposeful and voluntary. This was realized by placing the workers as agents and beneficiaries of the selling of sex.

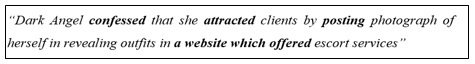

As shown in Figure

This portrayal is in contrast with the way media represents the workers as victims. Their victimization is constructed through the passive agency of their involvement. The news headline,

It is also evident that the positive-heroic image of the cops was reinforced through adjectives such as; ‘swiftly,' 'rescue,' and 'within four hours.' As indicated in Figure

It is also noted that the selected news articles used verbs and adjectives to highlight the workers' victimization such as, 'lured,' 'locked up,' 'imprisoned,' 'hit, 'forced into prostitution,' and 'rape.' The use of verb 'rape’ in the line ‘the woman was raped by the man several times’ was also crucial in enhancing the workers' victimization in which they were represented not only as victims of physical assaults, but also victims of sexual assaults. This line is instrumental as it gives a new interpretation toward the traffickers, not only as a commercial criminal but also as sex offenders.

Objectification

The news reports also frequently objectified sex workers in their portrayals of sex workers. Sex workers were depicted as objects to be consumed and sold, usually through the description of their prices. Another prominent strategy used to objectify sex workers is through metaphor. An example can be traced in a news report portraying a university student turned sex worker identified as ‘Dark Angel.' From the news headline, 'Undergrads netting tourists for sex,' (see Figure

Other examples of metaphors are evident when the premise is described as ‘den' (see Figure

Argumentative Strategies

In order to rationalize the negative representations of the workers,

Topos of Numbers

The growing number of sex workers in the country was justified through topos of numbers, in the form of statistics. Although the source of the statistics used to justify the growth of sex work population was not mentioned anywhere in the text, readers may not question the validity of these numbers as statistics are often deemed to be legitimate and accurate. The numbers also influence readers to consider the phenomenon not only as a fact but as a threat and a problem. Topos of numbers was also frequently applied to emphasize the sex workers' youth, where the workers were represented as either underage or women in their early twenties to legitimize their helplessness and vulnerability. Apart from age, topos of number was also used to highlight the workers' price, for example, in; '

Topos of Blame

Another argumentative strategy that could be traced in the articles is the topoi of blame. Topoi of blame are prevalent in justifying sex workers as criminals, and this can be seen in a direct quotation from an expert identified through her profession as a

Figure

Fallacy of Presumption

The fallacy of presumption is another argumentative strategy employed by the media to legitimize sex workers' negative representations. This representation is achieved using hasty generalization, where the workers were generalized according to their motivations in entering the sector. These categories were made without any support of evidence, and the examples can be seen in the comments made by a speaker who was individualized as

Based on the speaker's claims, foreign sex workers engaged in the sex trade because of the economic conditions of their home countries. As can be seen in Figure

Fallacy of Authority

It was also evident that the local media used the fallacy of authority to justify their negative representations of the workers. In the selected articles, the authorities were personalized through the reference of their titles, positions, or credentials.

In Figure

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings suggest that the local media employed

Meanwhile, as offenders, people in the sector were represented as the allies of illegal brothels, or greedy and materialistic individuals selling sex voluntarily for money. These representations were materialized semantically through role activation in the selling of sex, negative lexical items in referring to their activities as well as objectification that levelled the workers to objects and animals. The depictions will ultimately lead the public to consent to the sanctions applied to sex workers even when they are unfair and violate the workers' human rights.

These limited and negative representations are harmful to sex workers population. When sex workers continue being represented as the negative-other, persecution and violence against them will remain justified. It also trivializes the real issues affecting sex workers, such as violence and human rights violations that are common in the sector. Thus, this study reveals and problematizes how sex workers have been unfairly represented through and by the local media. For Malaysia to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) in reducing inequalities and providing fair access to safety, protection, and health services regardless and without prejudice; the Malaysian media must change the way it reports people in vulnerable groups of society, such as sex workers. This change can be done through inclusive news that brings in the workers' voices in news reports about them, to understand their day to day living realities.

Acknowledgments

This paper reports the findings from a study carried out in 2015 by Natrah Noor as part of the fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters of English as a Second Language (MESL) at the University of Malaya. The full report of the study and findings can be found in the unpublished dissertation entitled: Self-Other Representation of Sex workers in Malaysia.

References

- Foucault, M. (1978). The history of sexuality: An introduction. Pantheon Books.

- Gould, C., & Fick, N. (2008). Selling sex in Cape Town: Sex work and human trafficking in a South African city. Institute for Security Studies.

- Hallgrímsdóttir, H. K., Phillips, R., Benoit, C., & Walby, K. (2008). Sporting Girls, Streetwalkers, and Inmates of Houses of Ill Repute: Media Narratives and the Historical Mutability of Prostitution Stigmas. Sociological Perspectives, 51(1), 119–138. https://doi.org/10.1525/sop.2008.51.1.119

- Human Rights Commission of Malaysia. (2010). Annual Report 2010. https://www.suhakam.org.my/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/AR2010-BI.pdf

- Kantola, J., & Squires, J. (2004). Discourses Surrounding Prostitution Policies in the UK. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 11(1), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506804039815

- Lim, L. L. (1998). The sex sector: The economic and social bases of prostitution in Southeast Asia. Geneva: International Labour Office.

- Nagaraj, S., & Yahya, S. R. (1995). The sex sector: an unenumerated economy. University of Putra Malaysia.

- Noor, N. (2015). Self-Other representation of sex workers in Malaysia [Unpublished Master’s Thesis]. University of Malaya.

- Penal Code Act 574, Pub. L. No. Act 574 (2015). http://www.agc.gov.my/agcportal/uploads/files/ Publications/LOM/EN/Penal Code %5BAct 574%5D2.pdf

- Primoratz, I. (1999). Ethics and Sex. Routledge.

- Purcell, V. (1948). The Chinese in Malaya. Oxford University Press.

- Reisigl, M., & Wodak, R. (2017). The Discourse Historical Approach (DHA). In J. Flowerdew, & J. E. Richardson (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Critical Discourse Studies (pp. 23-61). Taylor & Francis.

- Scorgie, F., Vasey, K., Harper, E., Richter, M., Nare, P., Maseko, S., & Chersich, M. (2013). Human rights abuses and collective resilience among sex workers in four African countries: A qualitative study. Globalization and Health, 9, 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8603-9-33

- South China Morning Post. (2012, December 9). Vietnam breaks up rare anti-China protests. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/article/1101264/vietnam-breaks-anti-china-protests-hanoi

- Svinurai, A., Calvin, J., Agnes, J., Freeman, R., Mafa, P., Koketso, F., Chilwalo, N., Namoonga, R., Frank, H., Tiberia, N., Ilonga, H., & Winnie. (2019). “You Cannot Be Raped When You Are A Sex Worker”: Sexual Violence Among Substance Abusing Sex Workers in Musina, Limpopo Province. Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 16(4), 1-15

- SWEAT. (2013). Beginning to build the picture: South Africa National survey of sex worker knowledge, experiences and behaviour. https://www.hivsharespace.net/resource/beginning-build-picture-south-africa-national-survey-sex-worker-knowledge-experiences-and

- Syariah Criminal Offences Act 1997, Pub. L. No. Act 559 (2002). http://www2.esyariah.gov.my/ esyariah/mal/portalv1/enakmen2011/Eng_act_lib.nsf/858a0729306dc24748257651000e16c5/bced11b697691518c8256826002aaa20?OpenDocument

- The Star Online. (2012a, February 13). Women from China pay RM10,000 to work as prostitutes. The Star Online. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2012/02/13/women-from-china-pay-rm10000-to-work-as-prostitutes

- The Star Online. (2012b, February 9). Prostitutes now making house calls to avoid detection. The Star Online. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2012/02/09/prostitutes-now-making-house-calls-to-avoid-detection

- The Star Online. (2012c, January 31). Undergrads netting foreign tourists for sex. The Star Online. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2012/01/31/undergrads-netting-foreign-tourists-for-sex/

- The Star Online. (2012d, March 24). Cops rescue Viet women. The Star Online. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2012/03/24/cops-rescue-viet-women/

- The Star Online. (2012e, January 30). Foreign workers get satis-factory sex service. The Star Online. https://www.thestar.com.my/News/Nation/2012/01/30/Foreign-workers-get-satisfactory-sex-service

- The Star Online. (2012f, January 31). Cheap motels add to the growth of prostitution, says police. The Star Online https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2012/01/31/cheap-motels-add-to-growth-of-prostitution-say-police/

- UNGGAS Malaysia. (2012). Pelacuran di Malaysia semakin parah. http://sinarloronggelap.blogspot. com/2012/01/pelacuran-di-malaysia-semakin-parah.html

- Warren, J. (1994). Women and Chinese Patriarchy: Submission, Servitude, and Escape. In M. Jaschok, & S. Miers (Eds.), Women and Chinese Patriarchy: Submission, Servitude, and Escape (pp. 77–107). Hong Kong University Press.

- Wodak, R. (2001). Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857028020

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

12 October 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-088-4

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

89

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-796

Subjects

Business, innovation, sustainability, environment, green business, environmental issues, urban planning, municipal planning, disasters, social impact of disasters

Cite this article as:

Noor, N., & Abdul Hamid, B. (2020). Representation of Sex Workers in Malaysian News Media: A Critical Discourse Analysis. In N. Samat, J. Sulong, M. Pourya Asl, P. Keikhosrokiani, Y. Azam, & S. T. K. Leng (Eds.), Innovation and Transformation in Humanities for a Sustainable Tomorrow, vol 89. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1-13). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.10.02.1