Abstract

In this article the problem of interpretation of successful positive politeness strategy use is analyzed in terms of P. Brown and S. Levinson’s theory of politeness. In our research, we ulitized Principle of Relevance instead of Cooperative Principle and theory of politeness it was initially based on. The introductory part of the article reviews Grice’s Cooperative Principle, the way it was used as a basis for models of politeness, and the limitations of that principle, specifically in terms of evaluating the success of polite behaviour. Relevance theory is introduced as a possible alternative basis for the theory of politeness, containing a relevance scale for each utterance depending on the context of the interaction, thus enabling the evaluation of the success of polite behaviour. In the practical section of the article, the analysis of the politeness strategy “Notice, Attend to Hearer (his interests, wants, needs, goods)”, which is a part of the macrostrategy of positive politeness, as exemplified in the American talk-show discourse. The relevance of the politeness strategy is evaluated in terms of the hearer’s response and reaction to it. The success of the strategy is determined through the overall ratio of positive to negative reactions to the utterance containing it, as well as in terms of the specific positive reaction exhibited by the hearer.

Keywords: Relevance theorypositive politenesscooperative principle

Introduction

Framing the issue of politeness as the postulates of verbal communication is primarily connected with the name of Grice. In his work Logic and Conversation, Grice ( 1975) first formulated the Cooperative Principle, which consists of four postulates or conversational maxims (pp. 41-58). This issue has also been addressed by many modern Russian and foreign linguists in scientific works. For instance, Locher and Larina ( 2019) state that “im/politeness research has been a solid and growing research field in sociolinguistics, pragmatics and discourse analysis during the last four decades” (p. 873). Vlasyan and Kozhukhova ( 2016) in their article discuss some frequent ways of minimizing communicative pressure and describe the main obstacles of effective communication. Vlasyan ( 2016) in one of her works speculates about the influence of culture on communicative behaviour of speakers ( Vlasyan, 2016) and in the other work she writes that many linguists have shown a great interest for the importance of dialogical speech ( Vlasyan, 2017). Having studied many foreign articles, we cannot but make reference to Culpeper and Terkourafi ( 2017), who describe how concepts from linguistic pragmatics have shaped early politeness theories and critically examine the main politeness notions.

In our research, we ulitized Principle of Relevance instead of Cooperative Principle and theory of politeness it was initially based on. And, first of all, we would like to dwell on each maxim in more detail:

Maxims of quality:

Do not say what you believe to be false.

Do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence ( Grice, 1975, p. 45).

The lie is a phenomenon that has a universal character in different cultures, and it is socially acceptable within the framework of a certain "false minimum" that may vary in different cultures.

When evaluating a fact related to the addressee, the speaker has to take into account not only and not so much the factor of truthfulness of his or her evaluations, but also the reaction of the interlocutor to the way the latter is verbalized. Telling the truth is regulated by the ethical principles of a speaker and, first of all, by the beliefs of what and in what form it is possible to tell the other person and under what circumstances. Researchers of communication argue that social and communicative "truth" is often preferred in conversations in order to preserve favorable relations, rather than logical truth, but leads to a disturbance of social balance. Thus, it is appropriate to compliment: “What a fashionable hairstyle you have!” and inappropriate truthful: “What an ugly hairstyle you have!” (in relation to the "owner" of the same hairstyle).

Maxims of quantity:

Make your contribution as informative as is required (for the current purposes of the exchange).

Do not make your contribution more informative than is required ( Grice, 1975, p. 45).

The difficulty related to the implementation of this maxim is that it is very complicated to predict the necessary amount of information, because the ideas about the amount of information that should contain a statement may differ between a speaker and a recipient ( Thomas, 1995, p. 91).

Maxims of relation:

Be relevant.

Unfortunately, in his work, H.P. Grice does not give a detailed description of this postulate ( Grice, 1975, p. 46). In modern pragmatics different interpretations of the concept of relation are used.

For example, Dascal ( 1977) and Berg ( 1991) hold to a level approach. Although semantic and thematic levels are important, we cannot agree that their formal observance means fulfilling this maxim. Communication that occurs at the semantic level can be detrimental at the pragmatic level if the intentions of the participants in the communication diverge. For example, it is difficult to imagine the next conversation between a salesperson and a purchaser in a pet shop:

‘How about rabbits?’

‘Nice in a stew, isn’t it?’

But it will be quite relevant at the butcher shop.

The Principle of Relevance is distinguished, according to Sperber and Wilson ( 1995), includes the requirements contained in all other maxims (p. 50). The authors' criticism of the Principle of Cooperation and description of this theory are given below.

Maxims of manner:

Avoid obscurity of expression.

Avoid ambiguity.

Be brief (avoid excessive prolixity).

Be orderly ( Grice, 1975, p. 46).

Violation of this maxim occurs quite often because of emotional or psychological condition, for example, emotional excitement may be the cause of unrelated or confused speech. Moreover, in everyday communication, we often infringe upon the submaxim "Be brief" to be polite. Grice ( 1975) notes that the first three categories relate to what is said and the fourth to how it is said (p. 46).

The Cooperative Principle can be called the fundamental of "unwritten code" of speech etiquette. In real communication, it is always associated with the speaker's speech tactics, types of speech behaviour: the speaker can act as an "aggressor", an effective interlocutor or express a passive affirmative reaction. Obviously, implementation of some maxims is more obligatory than the others: a very talkative person is usually subject to less severe disapproval than a person who lies. Indeed, the importance of maxims of quality is so great that it should not be included in the general scheme. The other maxims come into effect only under the assumption that the maxims of quality are fulfilled. However, Grice ( 1975) believes that the role of these maxims does not differ significantly from that of the other maxims and that it is convenient to consider it among all other maxims.

Problem Statement

The Cooperative Principle of Grice ( 1975) was conceived as a universal set of rules defining cooperation between participants in social interaction. Grice uses the term "conversation" to denote social interaction, indicating that he was primarily interested in establishing agreements on meaning (both conventional and intentional) between the participants of communication. His approach to pragmatics anticipated postmodern theories, but he still remained focused on the ideology of defining language as a semiotic code. Grice himself did not claim that participants of communication would always stick to the maxims. On the contrary, the Cooperative Principle was originally based on the fact that it is impossible to abide all maxims. He notes that they can be supplemented by rules of other nature (aesthetic, social or moral), one of which is politeness. In communication, we constantly violate maxims for some reasons. One of the maxims may contradict the other, leading to the fact that the participant of communication, adhering to one maxim, will be forced to violate the other. Sometimes the participant of communication may consciously not abide the maxims for personal reasons.

Sperber and Wilson ( 1995) acknowledge that the Cooperative Principle of H. P. Grice takes the right way, but make many critical comments. First of all, they state that in order to meet the criteria of the model, all maxims must be derived from one of the main maxims of communication, which by their definition is the maxim of relation. The result of Sperber and Wilson’s (1995) joint study of pragmatics was the book “Relevance: Communication and Cognition”, which laid out a theory of relevance, the main statement of which is to define relevance as the only and determining value of information for the individual. In interpersonal communication, the guarantee of the relevance of a statement is its ostension, i.e., the obvious intention of the speaker to convey some information to the hearer. Ostensive behaviour provides the hearer with some fact at a time when they are able to admit that fact’s existence and accept it as true or likely true (p. 49). In Sperber and Wilson's theory, each statement in some discourse is an incentive that changes the hearer's cognitive environment. The speaker's statement is thus an indication of his or her action, about which the speaker informs the hearer(s) and changes the social context in which the speaker and the hearer(s) interact. The totality of all facts perceived by the hearer constitutes his or her cognitive environment. Ostensive behaviour of a speaker implies that each statement will by definition be guaranteed optimal relevance to the hearer, since knowing the speaker's intention to inform the hearer about something will mean that the speaker has done his or her utmost to produce a statement that contains new information related to information already known to the hearer. Such a statement will be relevant to the hearer's cognitive environment. The hearer should extract a sufficient amount of relevant information from the statement. This may be information that is relevant to the hearer, or information that the hearer understands to be most relevant to the speaker. Of course, in a communication situation, the hearer may not receive any new information from the speaker's statement, in which case, even if the hearer concludes that the speaker has done their utmost to say something optimally relevant, the relevance of that statement will still be low. Otherwise, the hearer may spend a lot of effort to understand a statement that will have little role in changing the general cognitive environment. Relevance in this theory is a sliding scale, the data of which will be different for the speaker and the hearer, for the hearer among themselves and depending on the context of communication. Some hearers may also use statements to extract some information that was not contained in the statements. One of the basic principles of relevance theory is the statement that no statement can be fully defined in relation to its meaning. The hearer discards all the propositional content of the statement, then uses the information from the context of the statement and his or her knowledge, highlighting the knowledge he or she most likely shares with the speaker in order to create some of his or her own assumptions deduced from the statement. The relevance of the statement is determined by its contextual effects and the efforts made to create assumptions ( Grice, 1975).

Research in the 1970s and early 1980s was characterized by the use of Grice’s Cooperative Principle as the basis for models explaining politeness as a way of achieving mutual cooperation and saving the

Brown and Levinson's ( 1987) work is based on the Cooperative Principle, attempting to resolve the contradiction described above by introducing the concept of "face" (pp. 61-62), borrowed from American sociologist Erwing Hoffmann. Saving the

However, in terms of relevance theory, the use of polite forms and strategies will not necessarily communicate politeness, or otherwise change the meaning of the message. Such behaviour will result in an additional level of communication only if the speaker's intense behaviour makes it obvious that he/she is more or less respectful of the hearer than it was obvious to him/her at the time, and this intention is obvious to both the speaker and the hearer.

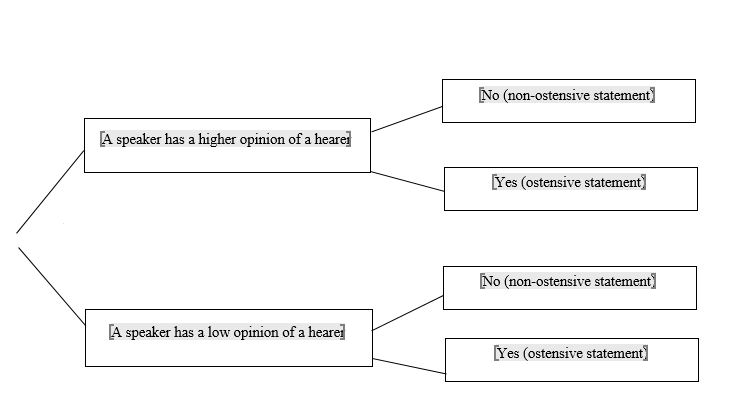

Designating the hearer as polite or impolite depends not only on the nature of the behaviour itself, but also on the motivation that the hearer attributes to the speaker. If the hearer's cognitive environment changes under the influence of statements that contain an intense speech behaviour of the speaker, and the relevance of this change to the hearer is information about the speaker's assessment, then the hearer comes to one of two possible conclusions: the speaker has a more or less high opinion about him or her than he or she expected. The hearer then has to decide whether the speaker intentionally made this impression on him or her. If the hearer considers the speaker's motivation to be sincere and the content of his or her statement to be true, then he or she will come to the conclusion that the speaker actually has a higher opinion of him or her. If, however, the hearer feels that the speaker is flattering him in order to achieve his deceptive purposes, or is trying to soften the damage to the hearer's face from a previously stated face-threatening act so as to restore the balance, then he will conclude that the speaker's opinion of him has not changed or has changed for the worse ( Jary, 1988).

Sorlin ( 2017) speculates in her article that Cooperative Principle and Brown and Levinson's politeness strategies, going beyond both frameworks to propose a model of manipulation that puts equal emphasis on Self and Other.

Research Questions

Given the fact that Brown and Levinson’s ( 1987) theory of politeness is initially based on Grice’s Cooperative Principle, can the model of politeness be altered to be based on the Principle of Relevance, in order to be able to evaluate the effectiveness of politeness strategies?

Can the macrostrategy of positive politeness be evaluated according to the Principle of Relevance in the talk-show discourse?

Purpose of the Study

Many contemporary scholars abovementioned have been studying different types of speech acts, for instance, Kozhukhova ( 2018) pays attention in her article to typical phrases of apology in English and Russian speech etiquette. As for foreign linguists we cannot but mention the article about speech acts in the talk-show genre, which we have examined with great interest ( Lubis, Purba, Sitinjak, & Tambunan, 2018). Markov ( 2018) dwelt upon the realization of negative and positive politeness in talk-show discourse in his early articles.

However, the purpose of our study is dialogue speech of talk-show as a part of politeness strategy “Notice, attend to Hearer”, based on the model of Brown and Levinson ( 1987) and the relevance theory of Sperber and Wilson ( 1995). “Notice, attend to Hearer” strategy suggests that the speaker should take notice of aspects of the hearer’s condition (noticeable changes, remarkable possessions, anything that demonstrates exclusiveness) (p. 103). Thus, this strategy represents some statement about the hearer's personality and actions, portraying him or her in the most favourable light, which the hearer may or may not agree with, depending on his or her understanding of the speaker's motivation and the validity of the statement.

Research Methods

We have analyzed all cases of using the "Notice, attend to Hearer" strategy as exemplified in the scripts of the American talk-shows "Conan" and "The Ellen Degeneres Show", with a total duration of 9 hours, and have studied the reactions of hearers of these strategies according to theory of Sperber and Wilson ( 1995) as part of the talk-show discourse.

The use of the "Notice, attend to Hearer" strategy of positive politeness by one of the participants in the conversation with respect to his or her interlocutor causes a reaction of agreement or disagreement, depending on what motives the hearer attributes to the speaker in the given situation. Agreement in English can be expressed by non-verbal means, such as nodding the head, lexically, particles "yes" or "yeah", verbs such as "wish" or "suppose" that have the meaning of desire or faith, or morphological means, by Indicative or Imperative Mood of the verb. Agreement may also be evidenced by the absence of direct logical contradictions between the hearer's further utterances and the speaker's words. Often, the hearer, in response to the polite statement of the speaker, continues the topic mentioned, thus accepting the changes in his cognitive environment, which caused the speaker's statement.

Findings

Having accepted the obvious polite or impolite behaviour of the speaker, the hearer will come to one of four possible conclusions, which are illustrated below in Figure

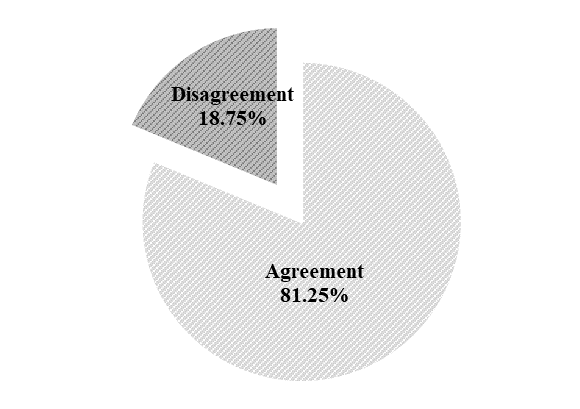

Sperber and Wilson ( 1995) admit that the process of making conclusions about the relevance of the interlocutor's statements is too complex to describe fully, and includes guesswork, analogies and reasoning in the absence of convincing evidence or supported by baseless statements. However, only conclusive evidence of the person's agreement or disagreement is required to demonstrate the success of politeness strategies.

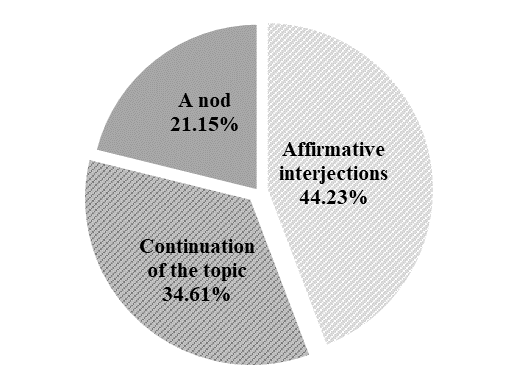

The most frequent means of expressing agreement in response to attention are particles "yes" or "yeah", as well as the set-expression "thank you" or "thanks". They represent 44.23% of all agreement reactions to the strategy of positive politeness under consideration.

The second most frequent means of expressing agreement was to continue the topic started by the speaker in his statement, in which the politeness strategy was applied. The absence of logical contradictions between the speaker's words and the hearer's response indicates that the hearer accepts this change in his or her cognitive environment as relevant. The continuation of the topic is 34.61% of all the reactions of agreement to the strategy under discussion of positive politeness. An example of such reaction is the answer of Tony Robbins, a famous business trainer and writer, to the statement of Ellen DeGeneres (broadcast - 03.12.2014):

'- Your seminars are not just about finance, but you help people with weight issues, with everything - confidence...'

'-...relationships, business. But before we begin, I wanna thank you for letting me on...

Tony agrees with Ellen's statement, continuing to list his qualifications, literally finishing her sentence. In doing so, he shows that he understands Ellen's motivation and finds her remark relevant.

The least frequent means of expressing agreement to the strategy of positive politeness under consideration is nodding. This is probably a result of the specific character of the talk-shows discourse, as it performs an entertainment function for the audience, and therefore the speech of the participants is more extensive and abundant in expressions. The nod constitutes of 21.15% of all the reactions of agreement to the strategy of positive politeness under consideration.

Disagreement with the statement of the interlocutor informing him/her that the politeness strategy has not reached its goal can be expressed by reciprocal silence or negative interjections such as "uh-uh" or "no". In such a situation, the hearer will refuse to continue the topic started by the speaker, as he considers the motivation for his statement to be insincere. Only 18.75% of the attempts to apply this strategy of positive politeness were met by the reaction of disagreement.

An interesting example of such behaviour is the reaction of Ellen DeGeneres, the host of "The Ellen DeGeneres Show", to the designation of her exclusivity as a person who changes other people's lives at the beginning of her conversation with Lewis House, a former footballer and media consultant ( broadcast - 20.04.2017):

"You know, what I loved doing was connecting with people like you, inspiring people who are changing the world, in every industry...

Ellen responds in silence to this comment, allowing Lewis to continue talking, although pauses in Lewis' speech allowed her to respond with a brief “yeah” or a nod. In saying this phrase, Lewis puts his hand on Ellen's wrist, but her body language does not show this fact: no change of the posture or smile. Since this strategy is used by the former footballer at the very beginning of his conversation with the presenter, the probable motivation for disagreement is that Ellen considered his statement flattery. Insincere use of such strategies to quickly achieve the location of interlocutors is characteristic of the speech behaviour of the Internet guru and their followers. In addition, Lewis came to Ellen's show to promote his new book. It is also likely that Ellen suggests the phrase "inspiring people who are changing the world" is excessive or unreliable.

Even if the speaker's intentions are sincere and his statement accurately reflects the facts obvious to all participants in the conversation, a positive politeness strategy can still be met with disagreement of the hearer when the speaker uses it to soften the damage from the previously said face-threatening act, and thus restore balance. In order for the hearer to consider the speaker's behaviour polite, he or she must conclude that he or she has a higher opinion of him or her than the hearer expected. However, in this case the cognitive environment does not change, but only returns to the state in which it was before the face-threatening act. An example of such disagreement is the reaction of Jack McBrayer to the positive politeness of Conan O'Brien, host of the talk-show "Conan", which he resorts to after several unsuccessful jokes about McBrayer's village past ( broadcast on 17.04.2017):

"Anyway, nice to see you here!

'- Uh-uh. No.''

The smile and tone of Jack's voice at this point expresses doubt rather than categorical disagreement. However, he and Conan O'Brien have been colleagues in the past, and remain good friends, so the unsuccessful jokes at the beginning of the conversation made it clear to Jack that Conan may hold him in lower regard than before. Paying attention later does not inform a higher opinion of Conan O'Brien about him, but only restores the balance.

'- You always want diet Mountain Dew, and if you don't get it, you get pretty fussy, don't you?'

"That is not true.

"Yeah, it is.

"I respectfully disagree.

Conan notes Jack's exclusivity as a person, pointing to his bizarre food preferences, but Jack either finds that comment to be untrue or he doubts the reasons that led Conan to note his exclusivity.

Conclusion

Thus, we have considered the main maxims of the Cooperative Principle of H. P. Grice, which originally provided scientific background for the politeness model of P. Brown and S. Levinson, as well as the Principle of Relevance, within the framework of the theory of relevance of Sperber and Wilson ( 1995), which is also assumed by the authors as a universal rule of social interaction. We assessed the success of the positive politeness strategy "Notice, attend to hearer" of the Brown and Levinson's ( 1987) model, according to the theory of relevance by calculating the correlation between the reactions of agreement and disagreement of interlocutors to the implication of the strategy, as well as comparing the frequency of different means of agreement. Within the talk-show discourse, the positive politeness strategy "Notice, attend to hearer" from the point of view of relevance theory is very effective, as its application has been met with 81.25% of agreement reactions from the interlocutor. Likewise, of all the reactions of agreement on this strategy, 78.84% were more active agreement in the form of stable expressions, interjections or continuation of the proposed topic. The results can be seen in the Figure

References

- Berg, J. (1991). The relevant relevance. Journal of Pragmatics 16(5), 411-425. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(91)90134-J

- Brown, P., & Levinson, S. (1987). Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Culpeper, J., & Terkourafi, M. (2017). Politeness and pragmatics. In: Culpeper, Jonathan, Michael Haugh & Daniel Kádár (Eds.) The Palgrave Handbook of Linguistic (Im)Politeness. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 11-39. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-37508-7

- Dascal, M. (1977). Conversational relevance. Journal of Pragmatics 1, 309-327. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(77)90026-1

- Grice, H. (1975). Logic and Conversation. In Cole P., Morgan (Eds.), J. Syntax and Semantics, Vol. 3: Speech Acts (pp. 41-58). New York: Academic Press.

- Jary, M. (1988). Relevance theory and the communication of politeness. Journal of Pragmatics 30, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(98)80005-2

- Kozhukhova, I. (2018). On apologising in the English and Russian languages. The European proceedings of social & behavioural sciences. IX International Conference “Word, Utterance, Text: cognitive, pragmatic and cultural aspects”, 75-79.

- Locher, M. A., & Larina, T. (2019). Introduction to politeness and impoliteness research in global contexts. Russian Journal of Linguistics, 23(4), 873-903. https://doi.org/10.22363/2687-0088-2019-23-4-873-903

- Lubis, F., Purba, N., Sitinjak, V. N., & Tambunan, A. R. S. (2018). Expressive Speech Acts in Ellen Show “An Interview with Ed Sheeran”. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 8(4), 138-144. Retrieved from https://www.ijhssnet.com/journal/index/4085

- Markov, I. (2018). Realizatsiya strategiy negativnoy vezhlivosti v amerikanskom i rossiyskom diskurse tok-shou [Realization of Negative Politeness Strategies in the American Talk Show Discourse]. Vestnik Chelyabinskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta, Filologicheskie nauki, 10(114), 143-149.

- Sorlin, S. (2017). The pragmatics of manipulation: Exploiting im/politeness theories. Journal of Pragmatics, 121, 132-146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2017.10.002

- Sperber, D., & Wilson, D. (1995). Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Thomas, J. (1995). Meaning in Interaction: An Introduction to Pragmatics. London: Longman.

- Vlasyan, G. (2016). Vliyaniye kul'tury na kommunikativnoye povedeniye govoryashchego [The impact of culture on communicative behavior of the speaker]. Filologicheskie nauki. Voprosy teorii I praktiki, part 1, 10(64), 42-45.

- Vlasyan, G., & Kozhukhova, I. (2016). Vezhlivost' v mul'tikul'turnom obshchestve: kamni pretknoveniya [Stumbling Blocks in Understanding Politeness in Multicultural Society]. Filologicheskie nauki. Voprosy teorii I praktiki, 2(56), part 2, 69-72.

- Vlasyan, G. (2017). Ustnyy razgovornyy dialog kak otkrytaya samorazvivayushchayasya sistema [Spoken dialogue as an open self-developing system]. Kommunikativnye issledovaniya, 4(14), 31-38.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

03 August 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-085-3

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

86

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1623

Subjects

Sociolinguistics, linguistics, semantics, discourse analysis, translation, interpretation

Cite this article as:

Markov, I., Vlasyan, G., & Zakharova-Dehamnia, V. (2020). Politeness And Relevance Theory: The Problem Of Interpretation. In N. L. Amiryanovna (Ed.), Word, Utterance, Text: Cognitive, Pragmatic and Cultural Aspects, vol 86. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 529-538). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.08.63