Abstract

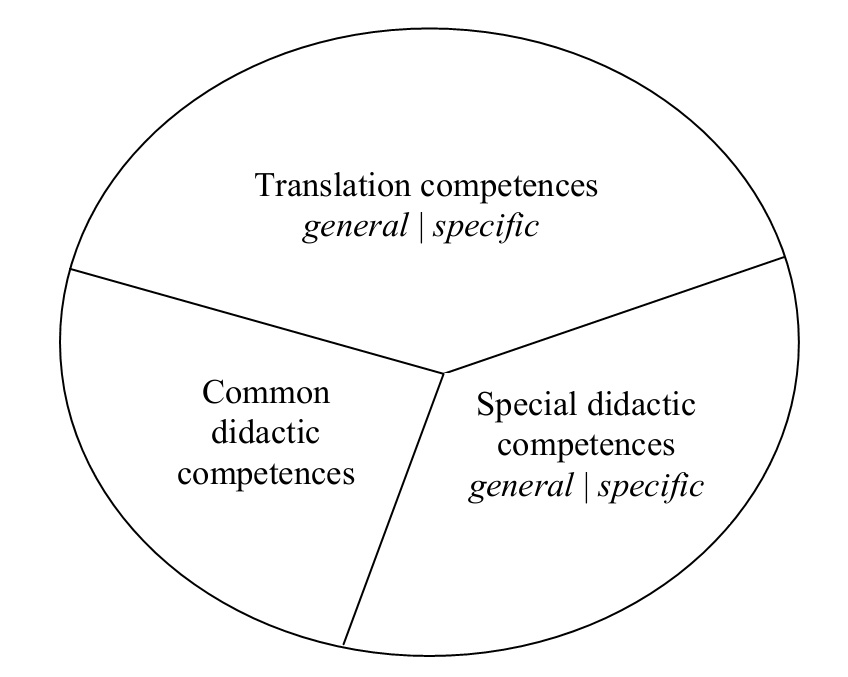

Since a large number of Russian universities have started training professional translators, a significant number of teachers of translation disciplines are required. The general requirements to university professors are defined in state regulations, but the requirements to a translator trainer have not yet been defined in Russian higher education environment. The problem is that Russian Translation Studies have not yet developed a list of competences that a translator trainer should possess, which cannot be said about Western Translation Studies. However, the analysis of empirical data shows that translation teachers in Russia only partially meet the general requirements specified in regulations. Worse still, universities that offer programs in translation have welcomed many practitioners who have vast experience in translation activities but lack knowledge of how to teach students. It exacerbates the problem of specifying competences of translator trainers. Our literature review showed that translation scholars unanimously believe that the short list of mandatory competencies for a translation teacher includes ability to translate, knowledge of translation theory and teaching skills, which is expressed in a certain set of competencies. A general model of translator trainer’s competences is proposed in the article. The model comprises translation competences, common didactic competences and special didactic competences. Translation and common didactic competences are naturally associated with special didactic competences, clarifying and specifying them.

Keywords: Translator trainer’s competencetranslation competencesdidactic competencesgeneral translation competences modeltranslation teacher’s profile

Introduction

Upon the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, the environment for the translation activity in the country has changed dramatically: a translation market emerged, which entailed the necessity of training a large number of translators/interpreters who are expected to satisfy the needs of the market.

Responding to the challenges of the time, to the transformations in the Russian society, the Russian higher education system has also transformed. In particular, many universities began to train translators/interpreters within various education programs. The number of such institutions is very hard to calculate; still some experts believe that it can be 120-140. The number is enormous even for such a huge country as Russia, especially when we take into account that the Soviet Union could boast of not more than five higher education institutions that were engaged in training translators. Certainly, newly emerged translation schools had no experience in this field of activity. But the main problem is that universities required and still require a large number of trainers who are capable of training translators. As a result, the sizable staff of translation teachers welcomed many people with different educational background, different experience in translation and teaching and with different vision of the essence of translation activity.

Problem Statement

We have all reasons to believe that the situation in Russian education system differs from that in other countries. It required at the very outset to define the general approaches to training translators who would meet the requirements of the translation industry ( Malenova, 2018a), to define the goals and objectives of the translators training, to develop methods of teaching various types of translation/interpreting and to formulate the requirements to competences of those who were expected to solve these tasks, i.e. trainers. Universities were very quick in responding to the challenge, and now there is no shortage of speculative studies devoted to competences of translators/interpreters, to the issue of forming professional translator’s mentality, i.e. professionally sound attitude of the translator to performing his/her activity, to methods of teaching various kinds of translation/interpreting, etc. These issues are broadly discussed at numerous scientific conferences and in their proceedings. But the question “What competences should a translation teacher possess?”, i.e. the question about the mere personality of a translation teacher, is not answered yet. It is even never asked. Thus, despite the similarity of the situations in Russia and the West, Russian Translation Studies are far behind Western Translation Studies.

Research Questions

The conducted research aims to answer the following question:

What is the situation with determining the competences of a translator trainer in modern Translation Studies?

What impact do government education policies and national traditions have on shaping requirements to teachers?

What are the general requirements to teachers of translation, and how do these requirements relate to the theoretical provisions adopted in Translation Studies?

What are the existing competence models for a translation teacher?

Answering these questions will be instrumental in creating a professional profile of a translation teacher.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the paper is to analyze the main approaches to defining translator trainers’ competences with due account of the requirements of the translation industry and the latest achievements of the Western Translation Studies as well as to specify the competences which are most significant in the education context in Russia. The more so as the consideration of national peculiarities of the given economy and the given education system is viewed by many scholars as one of the most significant methodological principles that help solve practical tasks. For example, Kelly ( 2008) argues that “careful attention needs to be paid, then, to institutional and local context, despite the internationalization of higher education and the globalization of the translation profession, which should be taken into account in trainer training” (p. 115). Even programs of training translators can be different in different cultures. Moreover, many Russian translation agencies, even small ones, offer courses of various types of translation, which is not the case abroad. Apparently, competences of those who teach translation are not always a matter of concern for the management of such agencies. So, it is worth mentioning that we shall consider this issue exclusively in relation to the higher education system, though some of our conclusions may also relate to the training of translators in non-university educational programs.

To define the competences that a translation teacher should possess, it is necessary to create a general model of such competences. Classification of the types of competences, even presented in the most general form, will allow to create a professional profile of a translation trainer.

Research Methods

Methods of theoretical research were used to solve the questions raised and to achieve the goal of the study. First of all, it is analysis method used to understand the essence of theoretical views of researchers presented in scientific works. The synthesis method allowed us to draw certain conclusions summarizing the results of comparing the theoretical positions presented in the works of Western translation scholars. The method of mental modeling was applied to create a general model of the translation teacher’s competence. At the same time, it should be noted that this model is the result of using the combination of the above methods.

Findings

General Requirements to Translator Trainers Competences in Russia

One of the peculiarities of the Russian higher education system is its rather strict regulation by the state authorities. Educational programs in higher education institutions are implemented in accordance with federal state educational standards adopted for each training area or major, and the requirements to the qualification of teachers are defined in the professional standard “Teacher of vocational training, professional education and additional professional education” approved by the Professional Standard of the RF, order No 608H ( Professional Standard…, 2015). Administrators of higher education institutions are obliged to organize the activities of the universities and, in particular, to recruit teachers with due regard to the existing federal regulations and in full compliance with them. The definition of requirements to university professors in federal regulations offers hope that, firstly, these requirements are sufficiently clear and specific, and secondly, universities will employ professors capable of fulfilling their mission effectively.

However, the requirements to the competence of university teachers are too general, which means that when it comes to defining the competence of teachers involved in training specialists for a certain industry, it is necessary to interpret the provisions of the professional standard. Given the space limitations for this paper, we shall not dwell on the structure of the professional standard, but shall pay attention to only some of its provisions, the interpretation of which can help us to come to a sufficiently clear definition of the competencies of translation teachers.

The professional standard contains a list of requirements to skills and knowledge of teachers. In particular, the following requirement to skills is noteworthy: “to perform an activity and/or demonstrate elements of activity mastered by the learners and/or to perform tasks in the curriculum of a subject, course, discipline (module)” ( Professional Standard…, 2015, p. 8). In other words,

Another provision of the professional standard requires to use pedagogically grounded forms, methods and techniques of organization of students’ activity, to apply modern technical means of education and educational technologies, to carry out e-learning, to use distance educational technologies, computer technologies, etc. ( Professional Standard…, 2015). In the most general form, this requirement can be formulated as follows:

The professional standard contains requirements not only to the skills of the teacher, but also to his/her knowledge. In particular, it is really important to have knowledge of the scientific and technical field and/or professional activity taught, current problems and trends in the development of the field ( Professional Standard…, 2015). This means that a translation teacher needs to understand the peculiarities of the translation industry organization, to know the trends of its development, to understand the requirements of the translation industry to translators and specialists of related professions in order to focus his/her teaching activities on developing the qualities that will help students meet these requirements. However, in Russian conditions, the knowledge of some translation teachers about the trends in the translation industry and its requirements to translators is clearly insufficient.

Still another requirement to the knowledge of translation teachers would help to solve this problem, at least in part: to know the requirements of the federal education standards, model programs and curricula of the practical training in the profession, the content of relevant textbooks and manuals ( Professional Standard…, 2015). As far as standards, model programs and curricula are concerned, university lecturers are quite familiar with them, which cannot be said about the so-called “prospective employers” involved in teaching. The situation with textbooks and manuals is even more unfortunate. Many teachers are still guided by textbooks published 30-40 years ago, and, accordingly, learn or still share the outdated ideas underlying these textbooks and manuals. It should be admitted, however, that so far there are very few sources in Russia from which teachers can learn modern knowledge about the specifics, goals, and patterns of translation activity, and about professionally justified approaches to solving translation problems. But the main problem is that some teachers of translation do not seek to acquire this intimate knowledge, naively believing that good command of a foreign language is a necessary and sufficient condition for quality translation or its teaching.

Meanwhile, many professors also have to both supervise students’ research and conduct research themselves. In this respect, the situation in Russia differs little from that in the West. The standard also requires that a teacher should know the role of the subject, course, discipline (module) to be taught in the basic professional educational program ( Professional Standard…, 2015).It implies not only the knowledge of the role of the subject in the educational program, but also the ability to interact with teachers of related disciplines, necessary to avoid clashes of and contradictions in the theoretical attitudes used in teaching different disciplines.

The general requirements of the professional standard are only partially met when translator training is organized. However, their interpretation makes it possible to determine what competencies a translation trainer should have. Unfortunately, so far this issue has not been the subject of active discussion in the Russian university community, which cannot be said about the situation abroad. Therefore, it seems necessary to consider the approaches of Western researchers to solving this problem.

Translator Trainers’ Competences in Brief: Western Approach

Over 30 years, the problem of training translation trainers and defining their competences became a matter of discussion in Translation Studies in the West. Many recent editions discuss the most fundamental problems of training translator trainers ( Colina & Angelelli, 2017; Haro-Soler, 2017; Li, 2017; Massey, 2019; Massey, Kiraly, & Ehrensberger-Dow, 2019; Orlando, 2016; Orlando, 2019; Sawyer, 2019; Wu, Wei, & Mo, 2019), methods of teaching various types of translation and interpreting ( González-Davies & Enríquez-Raído, 2016; Kiraly, 2016; Setton & Dawrant, 2016), the T/I teacher’s professional profile ( Pym & Torres-Simón, 2016) as well as requirements to competences of translation trainers.

The most significant contribution to defining and classifying translation teacher’s competences has been made by Dorothy Kelly. In ( Kelly, 2005, p. 151) she states that “the different areas of competence or expertise required in order to be a competent translator trainer are:

Professional translation practice,

Translation Studies as an academic discipline,

Teaching skills.”

The quote suggests that to have professional experience in translation and knowledge of translation theory is a must for a translation teacher. But the most essential area of competence, i.e. the central competence, is teaching skills subdivided into “subcompetences”:

Other approaches to classification of teachers’ competences can result in somewhat different models. Below we shall dwell upon one of them.

Translator Trainers Competences Model: Another Approach

One of the co-authors of this paper (D.N. Shlepnev) proposed a general model, or a framework structure, of a translation teacher’s competences. A conference presentation of this model and the corresponding publication are currently being prepared.

The starting point is as follows. The proposed model is not intended to be a competitor or a substitute for existing models and lists of competencies of a translation teacher ( Kelly, 2005; Kelly, 2008; The EMT…, 2013). Its primary goal is to become a practical tool for analysis and reflection. We can say that this framework structure sets a certain perspective through which it would be advisable to look at the translation teacher's competences and evaluate their composition, nature and specificity. It is also an additional opportunity to consider and compare existing or future models, as well as an additional opportunity to systematize the competences themselves.

What is particularly important in the proposed model is the fact that it allows to pay attention to some nuances – however, essential – that are not always properly understood. They are not realized exactly in the university context – in teaching and in appointing translation teachers. And this comes down to the problem of understanding the requirements to teachers.

The model is shown in Figure

We propose to differentiate between three main modules:

Professional translation competences do not need any comment. What matters here is the fact that a translation trainer must have translation competences: we have already seen that today this requirement is self-evident and no longer requires special argumentation in a professional context. It’s another matter that, unfortunately, persons with inadequate qualifications may sometimes be involved in teaching a particular translation discipline. The list (or model) of translation competences is a separate big issue on which we will not dwell here.

Two other modules are important not from the purely theoretical perspective, i.e. in terms of classification. Here we also take for granted the statement that translator training is a separate specific activity, and simply “being a practitioner” is not enough for training.

So, a teacher as such, regardless of the subject (s)he teaches, should possess common didactic competences. It should be noted that, in fact, this is what differentiates the profession of a teacher as a practical activity from other professions.

In our case, special didactic competences are related to the teaching of translation disciplines.

Translation and common didactic competences are naturally associated with special didactic competences, clarifying and specifying them (interrelation and openness of borders is marked with a dashed line).

And finally, another step from general to special: translation and special didactic competences are divided into general and specific.

General competences imply the requirements to a translator or translator trainer “in general”, regardless of the type of activity or the discipline taught. Specific competences relate to specific translation activities or disciplines.

It might seem that the scheme presented is just a descriptive construct. But it allows considering the following practical issues, mainly, by means of moving from general to special.

Let us compare common didactic and special didactic competences (their common component). An important question arises: are special didactic competences only a specification of common didactic competences (actually, by adding the word “translation”) or do they have their own specificity?

It is the second part of the statement that is true. Accordingly, if there may be requirements to a translator trainer – precisely, a teacher of translation – that cannot be directly deduced from the common didactic competences by simple clarification (adding the word “translation”, etc.); they must be identified and accounted for. And it is especially important not in theory, but in practice.

In the article under preparation it is suggested that such specific requirements include, for example, the ability to explain linguistic aspects (language proficiency is, strictly speaking, the sphere of professional translation competences); the ability to provide and explain relevant information of different nature that is somehow related to the given type of translation activity, the given subject area, etc.; possession of relevant knowledge of Translation Theory and didactics and the ability to use it. These components are not directly derived from common didactic requirements, as opposed to, for example, the ability to design or implement a curriculum, etc. Perhaps the knowledge and skills associated with a code or codes of professional ethics and specified by EMT ( The EMT…, 2013) can also be added to these three examples.

2. Let us compare the general and specific components of translation and special didactic competences. It is not always recognized in the education environment that specific types and spheres of activity, specific types of translation inevitably imply specific competences – necessary for performing these specific activities. For professional translators this is self-evident, and sometimes the requirements are fixed in certain documents (i.e. here we mean specific translation competences).

Accordingly, there are two things to emphasize.

Teaching a translation discipline or any assignment or exercise given to students should automatically imply the following requirement:

the teacher must be familiar with this type of translation activity, understand its specifics, requirements and be able to perform these activities and tasks professionally .It is not a question of making detailed lists for all types of activities: let us be realistic. But a very clear understanding of the problem is absolutely essential. And it should be understood not only by (future) teachers, but also – and most importantly – by their superiors, those people who appoint teachers and distribute the academic load among them. It is here that we find, at least in Russian reality, some unfortunate mistakes: a lack of understanding that a “translation teacher” is by no means a teacher of any kind of translation; a lack of understanding that translation activity is diverse, and the discipline “Translation” requires differentiation.

It may be noted that the scheme presented, on the one hand, clearly summarizes what is known and, on the other hand, draws our attention to the questions that do not always receive it, above all, in practice, i.e. in the university context.

Conclusion

A specific feature of the Russian education system is its strict regulation by state authorities, which, in particular, is manifested in the formulation of general requirements to university professors in the professional standard “Teacher of professional training, professional education and additional professional education”. However, these requirements are general and do not take into account the specifics of the subject area to be taught. The analysis of teaching translation subjects in Russian universities shows that even these general requirements to the competence of a translation teacher are only partially met in practice.

The situation in Russia is paradoxical: despite the fact that the education system is bureaucratized, it does not know the requirements to the competencies of translation teachers that are clearly defined and spelled out in standard regulations. Theorists learn about them from Western sources, and practitioners derive them intuitively from their own experience. Therefore, the requirements to the competence of a translator trainer remain a matter of discussion.

There is no doubt that the very general requirements to a translation teacher are: to be able to do what students are taught, i.e. to translate; to know the provisions of Translation Theory; to be able to teach.

In a more systematic way, the requirements to translator trainers can be presented as a general model that includes: translation competencies, common didactic competencies and special didactic competencies. Discussion of the presented model gives an opportunity to pay attention to the issues which are ignored in the higher education system.

Acknowledgments

The reported study was funded by RFBR, project number 20-013-00149.

References

- Colina, S., & Angelelli, C. (Eds.) (2017). Translation and Interpreting Pedagogy in Dialogue with Other Disciplines. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- González-Davies, M., & Enríquez-Raído, V. (2016). Situated Learning in Translator and Interpreter Training: Bridging Research and Good Practice. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 10(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2016.1154339

- Haro-Soler, M. (2017). Teaching Practices and Translation Students’ Self-efficacy: A Qualitative Study of Teachers’ Perceptions. Current Trends in Translation Teaching and Learning English, 4, 98-228.

- Kelly, D. (2005). A Handbook for Translator Trainers: A Guide to Reflective Practice. Manchester: St. Jerome.

- Kelly, D. (2008). Training the Trainers: Towards a Description of Translator Trainer Competence and Training Needs Analysis. Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction, 21(1), 99-125. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.7202/029688ar

- Kiraly, D. (Ed.). (2016). Towards Authentic Experiential Learning in Translator Education. Göttingen: V&R unipress/Mainz University Press.

- Li, X. (2017.07.28). Teaching Beliefs and Learning Beliefs in Translator and Interpreter Education: An Exploratory Case Study. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 12(2), 132-151. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2017.1359764

- Malenova, E. (2018a). Podgotovka perevodchikov v vuze: ozhidaniya i real'nost' [Academic teaching of translation and interpreting: expectations and reality]. Bridges. Translators’ Journal, 3(59), 57-66.

- Malenova, E. (2018b). Academic Teaching in Translation and Interpreting in Russia: Student Expectations and Market Reality. English Studies at NBU, 4, 101-116.

- Massey, G. (2019). Translation teacher training. In Laviosa, S. & Gonzalez-Davies M. (Eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Education (pp. 384-399). London: Routledge.

- Massey, G., Kiraly, D., & Ehrensberger-Dow, M. (2019). Training the translator trainers: an introduction. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 13(3), 211-215. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2019.1647821

- Orlando, M. (2016).Training 21st Century Translators and Interpreters: At the Crossroads of Practice, Research and Pedagogy. Berlin: Frank & Timme.

- Orlando, M. (2019.08.17).Training and educating interpreter and translator trainers as practitioners-researchers-teachers. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 13(3), 216-232. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2019.1656407

- Professional Standard “Teacher of professional training, professional education and additional professional education” (2015). Retrieved from: http://fgosvo.ru/uploadfiles/profstandart/01.004.pdf

- Pym, A., & Torres-Simón, E. (2016). The Professional Backgrounds of Translation Scholars. Report on a Survey. Target, 28(1), 110-131.

- Sawyer, D. B. (2019).Interpreting teacher training. In Laviosa, S., & Gonzalez-Davies, M. The Routledge Handbook of Translation end Education. London: Routledge.

- Setton, R., & Dawrant, A. (2016). Conference Interpreting: A Complete Course. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- The EMT Translator Trainer Profile. Competences of the Trainer in Translation (2013). Retrieved from: http://docplayer.net/14445272-The-emt-translator-trainer-profile-competences-of-the-trainer-in-translation.html

- Wu, D., Wei, L., & Mo, A. (2019). Training translation teachers in an initial teacher education programme: a self-efficacy beliefs perspective. Perspectives, 27(1), 74-90. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2018.1485715

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

03 August 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-085-3

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

86

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1623

Subjects

Sociolinguistics, linguistics, semantics, discourse analysis, translation, interpretation

Cite this article as:

Sdobnikov, V. V., Shamilov, R. M., & Shlepnev, D. N. (2020). The Basic Requirements To Translator Trainers Competence. In N. L. Amiryanovna (Ed.), Word, Utterance, Text: Cognitive, Pragmatic and Cultural Aspects, vol 86. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1227-1236). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.08.141