Abstract

Tolerance is a necessary characteristic of the educational environment of a university. In this regard, the problem of studying the conditions and factors for the formation of student tolerance remains relevant. This is complicated by the absence in psychology of a single conceptual approach to understanding this phenomenon, its psychological specificity not being clearly defined. The authors consider personality tolerance as an integrative, hierarchical formation. External, surface components of which are specifically directed dispositions, for example, tolerance to representatives of another culture or to other social groups. The article presents the results of an empirical study of tolerance of students from multi- and mono-ethnic families. It was assumed that the features of socialization in a multi-ethnic family will affect students' ethnic tolerance – it will be higher than the tolerance to other social groups, and then among respondents from mono-ethnic families. As a result, no significant differences between the groups were revealed. At the same time, the highest rates were observed specifically for students from multinational families, and precisely on the scale of “ethnic tolerance”. In the same group, the results on the scales of “ethnic” and “social tolerance” are statistically different at the level of the trend.

Keywords: Personal tolerancesocial tolerancestudents from mono-ethnic familiesstudents from multi-ethnic familiestoleranceethnic tolerance

Introduction

In any country in the world, successful universities are centers of intercultural communication. Tolerance is a necessary characteristic of the educational environment of a university. In this regard, the problem of studying the conditions and factors in the formation of tolerance of university students, and tolerance as a psychological phenomenon, in principle, remains relevant. This is complicated by the absence in psychology of a single conceptual approach to understanding this phenomenon, its psychological specificity not being clearly defined. The complex, multidimensional nature of tolerance is reflected in a multitude of definitions and conflicting models. It is considered a personal attribute, an integrative mental education, including a set of personality traits and processes, disposition, attitude or attitude, etc. (Bardier, 2005; Bondyreva & Kolesov, 2003; Doroshina, 2016; Klejberg, 2012; Uglova, 2008).

In our opinion, personality tolerance is a complex integrative, hierarchical formation that determines the emotional and behavioral reactions of an individual in those cases when they are faced with something different from their ideas, unusual and unacceptable. The core of this structure is composed of implicit basic beliefs about the positive nature of a person, a value attitude to a person – to other people, to the myself. The external, surface components of this structure will be specifically directed dispositions. For example, tolerance to representatives of another culture, to the elderly, the poor or the mentally ill, etc. The prerequisites or inclinations of personal tolerance may be the physiological and psychophysiological characteristics of an individual, such as: stability and balance of nervous processes, emotional stability, low reactivity, etc. They are not determinative, but facilitate its formation.

The underlying personality substructures of tolerance are more stable. The formation and transformation of tolerant attitudes aimed at specific social groups and processes will be influenced by many factors (experience in interacting with specific people, the nature of education, the characteristics of primary and secondary social groups in which the individual was included, etc.).

Problem Statement

Regarding the factors, conditions and mechanisms of tolerance, among researchers there is even less unity and certainty. The systematization of factors is almost completely absent. In the existing works on this topic, more attention is paid to the intrapersonal determinants of tolerant dispositions – personality traits that are considered either as factors, or as prerequisites, or as components of tolerance (Doroshina, 2016; Kapustina, 2008; Markova, 2009; Uglova, 2011).

The nature of the influence of primary social groups on the formation of tolerant attitudes has hardly been studied. It is indisputable that the influence, first of all, of the family is crucial for the formation of the personality, its basic attitudes, norms of social interaction, values, etc. (Cooley, 2016). But what specific characteristics of the family will determine tolerance, and what specific substructures of personality tolerance will they determine? For example, do manifestations of ethnic and racial intolerance of parents contribute to the formation of the same position in children (Marchenko, 2011)? Or will the parent's style of communication with the child be crucial? All of these issues remain open.

From our point of view, for the formation of ethnic tolerance, it is important if the family has a peaceful coexistence of different cultural norms and traditions. From this perspective, respondents who were brought up in a multi-ethnic family are of interest to our study. A multiethnic or multinational family is a family in which family members have different ethnic identities or nationalities. Conversely, a family where everyone belongs to the same ethnic group is called mono-national or mono-ethnic.

Research Questions

Is the tolerance of students from multi- and mono-ethnic families different?

Is the ethnic tolerance of students from multi-ethnic families more pronounced than their social tolerance?

Purpose of the Study

If a child, from the moment of birth, grows up and develops in a family where the merging, mixing of cultural norms and traditions of different ethnic groups is an everyday natural reality, this cannot but affect his attitude to cultural differences. Thus, assuming that the features of socialization and inculturation in a multiethnic family will affect specific types of tolerance, we set a goal in this study to test the following hypotheses.

Ethnic tolerance of students from multiethnic families will be higher than among students from mono-ethnic families. Moreover, other types of tolerance, in two groups of students, will not differ.

Perhaps, in subjects from multinational families, ethnic tolerance will be more pronounced than attitudes of tolerance aimed at other social groups.

Research Methods

To achieve these goals, at the empirical stage of the study, questionnaires, psychodiagnostics, and methods of statistical data analysis were used.

Initially, we were faced with the task of forming a sample of the study. For this, a special questionnaire was developed, with which we received information about the age, gender, ethnic identity of students, and, most importantly, the national composition of their families. In total, more than one hundred people were interviewed (students from universities in the north-west of Russia, between the ages of seventeen and twenty-one), of which fifty made up a sample for the study. The sample was divided into two groups.

The first group (twenty-six people, thirteen males and thirteen females) included only those respondents who were brought up in families, where all close relatives in their environment (primarily mom and dad) consider themselves to belong to one ethnic group and one culture, share traditions of their people. These were Russian, Ukrainian, Chuvash, Belarusian, Armenian and other families.

The second group (twenty-four people, twelve males and twelve females) included only those respondents who were brought up in families where the mother and father are of different nationalities and retain, at the moment, different ethnic identities. In our case, these were the following options: Russian – Ukrainian, German – Russian, Belarusian – Russian, Ukrainian – Belarusian, Agul – Lezgin, Lezgin – Uzbek, Armenian – Russian, Ukrainian – Tatar, etc.

It is important to note that the students, who came from multinational families, defined their ethnic identity in different ways themselves. In most cases, the ethnic identity of the child coincided with the identity of one of the parents. For example, in a family where the mother is Russian and the father is Bulgarian, the son also considers himself a Bulgarian. Or in a family where the father is Lezgin and the mother is Uzbek, the son considers himself a Lezgin. But there were other options too. Some respondents from this group had a bi-ethnic identity or a mono-ethnic identity, but of a different ethnic group. For example, in a family where the mother is Ukrainian, and the father is Abkhazian, the daughter identifies herself with one and the other nation. Or in a family where the father is gypsy, and the mother has a bi-ethnic identity (refers herself both to the Belarusian and Ukrainian ethnic groups), the daughter identifies herself with the Russian people. According to our observations, this is most often associated with the place of permanent residence.

To identify students' tolerance, at the next stage, the questionnaire “Tolerance Index” was used by Soldatova, O. A. Kravtsova, O. E. Khukhlaeva, L. A. Shaigerova (Soldatova & Shajgerova, 2008).

In addition to the general indicator of tolerance, the technique allows one to diagnose its following types:

ethnic tolerance;

social tolerance;

tolerance as a personality trait.

Ethnic tolerance is an attitude in the field of intercultural interaction, when the basis for accepting or rejecting a person is only their belonging to their or another ethnic group or race. Social tolerance characterizes the attitude towards representatives of various marginal, religious movements, minorities, and other people who are somewhat different from us, but are within the framework of their ethnic group. Tolerance as a personal property is a generalized characteristic of the worldview of a person as a whole, their basic beliefs. It largely determines a person’s attitude to the world, people, social processes, etc., including the two types of tolerance described above.

For statistical data processing, the Mann-Whitney difference criterion (U) and the Fisher angular transformation criterion (φ*) were used.

Findings

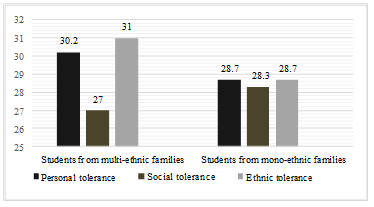

Initially, indicators of different types of tolerance of students from poly- and mono-ethnic families were measured and compared. The results are clearly shown in Figure 01

Having compared the results of studies of different types of tolerance within each group of subjects and between groups, the following can be said. The average values of the indicators of personal, social and ethnic tolerance of students from mono-ethnic families are almost the same. A greater variation is in the results among the group of respondents from multi-ethnic families. In the same group, as we expected, indicators for the parameter of “Ethnic tolerance” are the highest, and the indicators of social tolerance are the lowest.

For statistical analysis of the obtained data, the Mann-Whitney difference criterion (U) was used. Initially, the results of the two groups were compared among themselves. No significant differences were found on any of the scales. We can say that the severity of ethnic, social and personal tolerance in the two groups does not differ.

Then, the indicators of subjects from multinational families were compared, since we assumed that it was their ethnic tolerance that would be higher than other types of tolerance. Indeed, statistical processing showed that in this group the results on the scales of “ethnic” and “social tolerance” differ at the level of the trend (UE = 179, significance at the level of p ≤ 0.05).

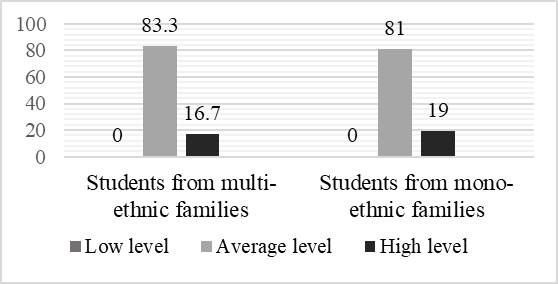

At the next stage, by summing the data on separate scales, students' tolerance indices were measured and compared. The integral indicators of tolerance of the two groups are very close (Figure 02)

The dominance of intolerant attitudes and intolerance towards others was not found in any of the respondents. Perhaps this is due to social desirability, although the survey was anonymous.

The vast majority of respondents – more than eighty percent in both the first and second groups – have an average level of general tolerance. This means that, within the continuum of “absolute tolerance – absolute rejection” they have a fairly wide range of attitudes towards different social groups and their representatives, or carriers of certain personal qualities. Therefore, in situations of social interaction, they can behave differently. But at the same time, for this part of the sample, a certain “healthy” balance of tolerant dispositions and intolerant attitude towards various social objects is characteristic.

Less than twenty percent of students from the first and second groups showed high values of general tolerance (and in the group of students from mono-ethnic families, there are a little more). Using the questionnaire to collect data, we understood that, in this case, a high level of tolerance will not always be an unambiguous indicator of the dominance of positive attitudes towards social diversity. Also, the high scores of these subjects may indicate their inherent conformity. Respondents are more likely to demonstrate a tolerant attitude, since they believe that this is a certain norm or value for their social environment or culture, and in reality, their tolerant attitude may be not expressed. An integral indicator of tolerance close to the maximum value may indicate blurring of the boundaries of the personality, pronounced infantilism, or indifference to the social environment. It may also be a manifestation of high social desirability.

We compared the percentages of subjects with a high and medium level of tolerance in the two groups using the criterion φ * – angular Fisher transform. No significant differences were found.

The average value of the tolerance index in a group of students from multi-ethnic families is not significantly higher, but it is higher – in general, they are more tolerant. But data analysis using the Mann-Whitney test (U) also confirmed the absence of significant differences. The results of the mathematical analysis of the data are presented in the Table

At the same time, it is interesting that the range of values of this characteristic in this group is noticeably larger (Table

Conclusion

Tolerance is a complex, systemic, multi-level concept. It is determined by a system of factors, and family is one of them. In our study, we did not reveal any significant differences in the ethnic, social and personal tolerance of students from multi- and mono-ethnic families. Although the integral indicator of tolerance of students from multinational families is slightly higher, nevertheless, there are no statistically significant differences between the groups.

At the same time, some peculiarities in the structure of dispositions of tolerance of students from multi-ethnic families were identified. The highest average value is noted precisely in this group, and precisely on the scale of “ethnic tolerance”. For students from multi-ethnic families, the results on the scales of "ethnic" and "social tolerance" are statistically different at the level of the trend. Also, respondents from multinational families are more likely to demonstrate extreme values of the tolerance index.

The problem of the influence of the family on the formation, degree of expressiveness and structure of tolerance requires further study.

References

- Bardier, G. L. (2005). Social psychology of tolerance. Saint-Petersburg, St. Petersburg University. [in Russ.].

- Bondyreva, S. K., & Kolesov, D. V. (2003). Tolerance (introduction to the problem). Moscow-Voronezh: MODE`K. [in Russ.].

- Cooley, C. (2016). Human Nature and the Social Order. Creative Media Partners: LLC.

- Doroshina, I. G. (2016). Tolerance: the psychological perspective. Akademicka psychologie, 1, 15-18. [in Russ.].

- Kapustina, N. G. (2008). Tolerance as an internal resource of personality. Siberian psychological journal, 30, 64-69. [in Russ.].

- Klejberg, Yu. A. (2012). Tolerance and destructive tolerance: concept, approaches, typology, characteristics. Society and law, 4(41), 329-334. [in Russ.].

- Marchenko, G. B. (2011). Tolerance of parents as a factor in the formation of tolerance of preschool children. Actual problems of psychological knowledge, 1(18), 101-105. [in Russ.].

- Markova, N. G. (2009). Formation of tolerance among young people as an indicator of the culture of interethnic relations. Siberian psychological journal, 31, 53-58. [in Russ.].

- Soldatova, G. U., & Shajgerova, L. A. (2008). Psychodiagnostics of tolerance of personality. Moscow: Smysl. [in Russ.].

- Uglova, T. V. (2011). Intrapersonal determinants of tolerant attitude to the other. Veliky Novgorod. Novgorod state University. [in Russ.].

- Uglova, T. V. (2008). Formation of tolerant attitude to other students. Vestnik Novgorod state University, 48, 78-80. [in Russ.].

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

26 August 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-086-0

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

87

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-812

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, teacher training, moral purpose of education, social purpose of education

Cite this article as:

Uglova, T., Lazareva, V. A., & Moiseev, D. V. (2020). Tolerance Of Students From Multi- And Monoethnic Families. In S. Alexander Glebovich (Ed.), Pedagogical Education - History, Present Time, Perspectives, vol 87. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 198-204). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.08.02.25