Abstract

The mentoring concept has evolved much in recent years and has become increasingly tied to

Keywords: Mentoringlearning organizationteam learningcooperation

Introduction

We live today in a world where the amount of information and the accelerated rhythm of change are too overwhelming for individuals to cope with. The rate of change is constantly rising, a rapid, unpredictable, non-linear change (Fullan, 2001). In this context, there is a growing need to shift the emphasis from individual learning to the dimension of social learning. The individual is no longer a lonely seeker of knowledge, but rather part of a learning community.

Schools are, in this respect, complex social communities that have the role of training young people for social and professional integration, through transfer of knowledge, development of abilities, norms, values and socially accepted values. Education’s main goal is not only to train students to live in this world, but also to improve it. Therefore, more than ever, the role of educational organizations is changing nowadays: the priority of each school is to stimulate creative individuals and innovators must be the priority of each school. Since there is too much information to be transferred to students, the school has to focus on how to obtain and organize information rather than to transmit knowledge. The networks of collaborative organisations that undergo a continuous process of renewal represent the organisations of the future. The most effective way to align with this goal is to transform schools into learning organizations.

Problem Statement

The concept of a "learning organization", derived from Schön's (1973) theoretical foundations, has become a strong source of inspiration for the academic and economic environment once the works of Senge (Senge, 1990, 1996; Senge, Kleiner, Roberts, Ross, & Smith, 1994) were published. According to him “a learning organization is a place where people are continually discovering how they create their reality. And how they can change it” (Senge, Kleiner, Roberts, Roth, & Smith, 1999, p.13).

Analysing subsequent specialty studies (DuFour, 2004; Garvin, 1993, 2003; Harris & Jones, 2010; Marsick & Watkins, 1999, 2003a, 2003b; Pedler & Boydell, 1996; Redding, 1997; Watkins & Marsick, 1997; Williams, Brien, & LeBlanc, 2012). I have synthesized some of the characteristics of a school seen as a learning organization: a learning school is governed by values shared by an entire collectivity; it prepares a school culture that is renewed through constant learning; it promotes learning anywhere; it prioritizes the improvement of human resources; it facilitates the learning of all its members and it is constantly transforming; teachers work in teams, sharing personal practices; it has an atmosphere of open and positive dialogue; it is an organization capable of creating, acquiring and transferring knowledge; it modifies its behaviour to reflect new knowledge and perspectives; leadership is flexible, supportive and common and it is permanently anchored to immediate reality.

Considering these aspects, Watkins and Marsick (1997), materialized seven dimensions in the model of learning organizations. These are (1) Continuous learning; (2) Inquiry and dialogue (3) Team learning (4) Embedded system; (5) Empowerment; (6) System connection (7) Strategic leadership.

In previous researches (Bradea, 2013, 2016, 2017), I have demonstrated that there is still a great deal to be done for the Romanian school to be seen as a learning organization. Proper development of the school within the community context requires an effort of will of the people involved, but also a managerial option. Although invested with the same social roles, schools operate in different communities, thus the degree of development depends on the community’s resources, on the management style adopted by the school leader, but also on the needs of the educational service users: children, families, adults. We can consider a school as being developed if it responds to a great range of its clients' needs, if it is prepared and involved in partnerships, if it is flexible, with well-trained and motivated employees (Bradea, 2013). If we talk about an organisational culture oriented towards the individual where professional qualities and competences matter more than the status in the institution's hierarchy, then this thing is possible. Because making full use of the individuals' potential is one of the fundamental values of a learning organization (Báez, 2019). It is a team culture which builds an interaction between collective values (such as cooperation, identification with the objectives of the organisation, teamwork, collective mobilisation) and individual values (appreciation of the individual, individual autonomy and freedom). The leadership should be flexible and stimulative, based on values like trust in people, in their creative abilities and self-control. This research showed that schools possess such values (Bradea, 2017).

This aspect of the culture of collaboration has also been part of the research of our postgraduate university for mentoring training. Although there is a legal framework in Romania for conducting mentoring programmes in schools, this is not the case. Their role is held by experienced teachers who, like mentors, are willing to help others develop in order to achieve success. They are ready to invest time and effort and they are ready to share knowledge and personal experience with the young teachers in a confidential manner and based on mutual trust and respect. It has also been pointed out that mentors play an important role in the socialization of beginner teachers, helping them to adjust to norms, standards and expectations related to teaching in general and to the specific nature of the school (Bullough & Draper, 2004; Feiman-Nemser & Parker, 1992; Wang & Odell, 2002). Mentoring must be seen as a two-way learning process that both mentor and mentee can benefit from. It has been shown that teachers in their mentor roles can also learn from beginner teachers who can come up with new ideas and provide new perspectives. The mentor-mentee relationship is sometimes seen as

Research Questions

The aim of our research was to analyse how mentoring can become part of a strategy for transforming school institutions into learning organizations. We aim to identify the strengths of this process as well as its the weaknesses, highlighting the need to prioritize mentoring as an essential part of a learning organization.

Purpose of the Study

Starting from the ideas presented above, the research had the following specific objectives (1) identifying teachers' opinion on the need for mentors in schools to support teaching staff in classroom practice; (2) identifying teachers' perceptions of teamwork in their organizations; (3) identifying teachers' perceptions about the nature of collaborative relationships within the organization.

The research sample consisted of 672 people (N = 672), all teachers from 11 pre-university schools in Bihor county, Romania (6 schools from urban areas and 5 schools from rural areas). The people included in the sample were chosen using the simple random sampling procedure, and they belonged to the following categories: according to gender: 91% females, 9% males, according to the school stage: 22% primary school teachers, 41% lower secondary school and 37% upper-secondary school, according to the area they teach in: 64% in urban area, 36% in rural area.

Research Methods

The main research method used in this study was the Dimensions of the Learning School Questionnaire (DLOQ), adapted after Marsick and Watkins (2003a, 2003b), Kools and Stoll (2016), OECD (2018), which over time was subjected to numerous validity tests, demonstrating that it is an appropriate tool for the characteristics of the learning organisation. It contains 65 items across eight dimensions: 1) developing a shared vision centred on learning of all students; 2) partners contributing to the school’s vision; 3) creating and supporting continuous learning opportunities; 4) promoting team learning and collaboration; 5) establishing a culture of enquiry, innovation and exploration; 6) embedding systems for collecting and exchanging knowledge and learning; 7) learning with and from the external environment; and 8) modelling and growing learning leadership. The dimensions were measured on a 6-point Likert scale (1 – Never, 2 - Almost Never, 3 – Rarely, 4 –Sometimes, 5 – Often, 6 - Almost Always). Each respondent completed the questionnaire online. The research was implemented from October, 2018 to April, 2019. Since our research does not assess schools as learning organisations, we have considered only two items from the second dimension as representative for the investigated issue. They were related to the defining criteria for dimensions 3 and 4.

Findings

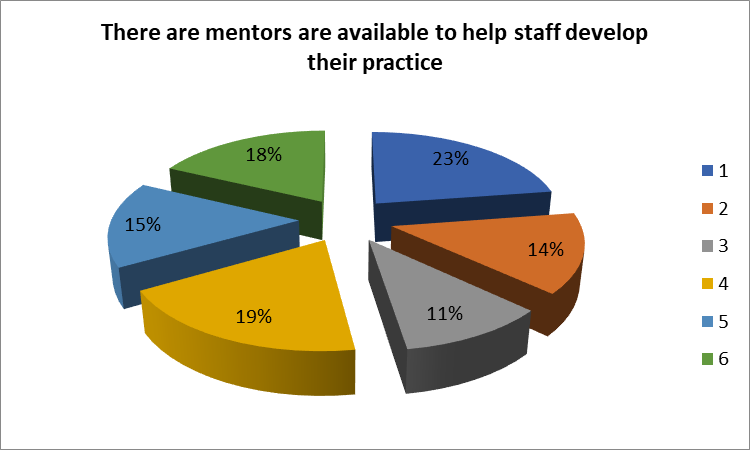

The quantitative interpretation of the results was performed by calculating the statistical frequency of the answers provided by the respondents. The results are presented below (Figure

Despite the legislation in this regard, in schools across Romania mentoring is not explicitly part of the basic model of the learning organisation. This is also highlighted in the figure above: most respondents, 23%, claim that there is nobody in their school to guide them in the development of class practice. Answers from the first part of the grid (1,2,3) show that almost half (48%) of the respondents benefit very little, or sporadically, of such guidance. The majority of those who benefit from experienced teachers, mentoring and school support (18%-Almost Always, 15%-Often) belong to rural schools, low-staffed organisations where collaborative relationships are prioritised. This is beneficial both for the one that needs support and for the organisation as a whole, through collaborative research, joint educational projects that increase the quality of the educational act, according to the vision of the school. Eller, Lev, and Feurer (2014) describe eight aspects of an effective mentoring relationship. These include open communication and accessibility; objectives and challenges; passion and inspiration; personal relationship; mutual respect and trust; knowledge sharing; independence and collaboration; and shaping the role. Responses from the second part of the grid show that these dimensions are not capitalized in all the schools. But there is certainty that schools, as learning organisations, can provide a structural context for mentoring. Leidenfrost, Strassnig, Schütz, Carbon, and Schabmann (2014) concluded that "any mentoring style is better than no mentoring at all" (p. 108).

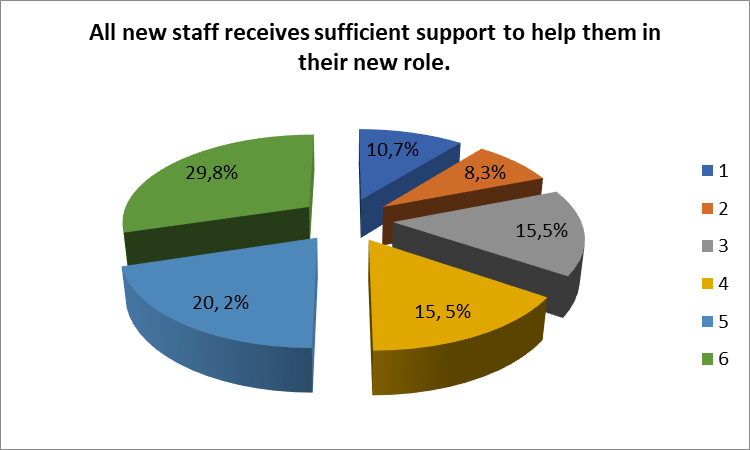

The answers to this item (Figure

The development of a strong culture of mutual support is defining in a school seen as a learning organization. Learning in such organizations is not additional, but complementary to personal learning. The results presented in Table

The idea that there is greater collaboration in rural schools than in urban schools is explained by the fact that these are generally smaller collectivities who spend most of their breaks together and are generally involved in several school activities (Bradea, 2017). As teachers are not divided on specialized subcommittees, jealousies generated by professional pride are almost non-existing.

Perhaps the most important feature of a productive collaboration is the desire of those involved to accept the feedback and to work on improving the activity (Louis & Kruse, 1995). The mean on this item (

Conclusion

A strong learning organization encourages collective effort rather than individual isolated efforts (Senge et al., 2000). A learning school is a place where learning teams can be seen everywhere. Within the team, everyone spends time identifying the issues to be solved and helping others solve these problems. In addition, each person is assessed on the basis of the desire to share experience with others in school learning (Báez, 2019).

Recently there have been more and more studies which include mentoring in the sphere of learning organization, assigning it a key role. A learning organization should offer teachers the possibility to continuously learn from each other, developing at the same time common action plans (Lieberman & Miller, 2008). And these action plans should start at the level of school. This should be a bridge that takes learning from the macro-knowledge level to the micro one by developing the teachers' professional abilities, embodied in practices and refinements required for implementation in school or in classroom. In this respect, mentoring is an important part within a learning organization. The principles of a mentoring relationship are entirely the principles that are found in the functioning of a learning organization.

Through our research we have confirmed certain aspects of the need of using mentoring as part of a strategy of transforming schools into learning organizations. Since there is no formal framework in Romania for the development of mentoring periods for beginner teachers, they find little support in their first years of profession and in the induction process (sometimes with the support of a specialist inspector, County Inspectorates or with the support of an experienced teacher from school). Taking into consideration the fact that there is a culture of collaboration between employees (even if at different stages depending on the organizational culture of each school), mentoring should become a priority for the educational policies in our country. The lack of coherence in the Romanian educational policy, the frequent changes to the organization of the educational system, the agglomeration of teachers with administrative tasks, sometimes only tangent to the educational field, the focus on competition and results (at all levels and for all employees) are just a few barriers in transforming our schools into true learning organizations. Schools, as well as other parts of the system, spend a lot of time and effort in analysing and reporting to their superiors a wide range of quantitative data, thus diminishing the attention that should be paid to qualitative sources.

Another aspect worthy of being taken into consideration is the inadequate way of assessing teachers in Romania (Blândul, 2011). The criteria focus exclusively on individual results without quantifying common results such as involvement in school life by providing expertise in the field, exchanges of experience, teachers’ role in implementing the school's operational plan. Employment cuts are also made on the basis of individual assessment which, in some cases, causes teachers to be selfish, individualized, to attend training courses without only to have a higher score. These practices cannot be found in a learning organization (Bradea, 2017).

When professional learning takes place within a system driven by common expectations and goals, in a collaborative atmosphere where each individual is valued, the result is a profound change not only for individuals, but also for the entire educational system. Under these circumstances, we believe that the first step towards beginners' becoming familiar with the culture and vision of a school can be through mentoring. The human relationships that are thus developed can build the foundation of a long-term collaboration at all levels within the institution. We hope decision makers understand the need of transforming schools into true learning organizations.

References

- Báez, D. (2019). El deber ser de las instituciones de educación media y superior sobresuresponsabilidaden la formación integral del ser humano [The duty of the institutions of secondary and higher education on their responsibility in the integral formation of the human being]. In M. El Homrani, S. M. Arias Romero, & I. Avaloz Ruiz (Eds.) La inclusión: una apuestaeducativa y social [Inclusion: an educational and social commitment] (pp. 27-39). Madrid: Wolters Kluwer.

- Blândul, V. (2011). Elements of Professor’s Teamwork in Scools. Practice and Theory in Systems of Education, 6(4), 353-360.

- Bradea, A. (2013). The school – from educational services distributor to learning community. Practiceand Theory in Systems of Education, 8(2), 185-191.http://epa.oszk.hu/01400/01428/00023/pdf/EPA01428_2013_02_185-191.pdf

- Bradea, A. (2016). Some aspects of school seen as a Professional Learning Community. Practice and Theory in Systems of Education, 11(4), 241-249. https://doi.org/10.1515/ptse-2016-0023

- Bradea, A. (2017). The role of Professional Learning Community in schools. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences, EpSBS, 468-475. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.57

- Bullough, R. V., & Draper, R. J. (2004). Mentoring and the emotions. Journal of Education for Teaching: International Research and Pedagogy, 30(3), 271–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260747042000309493

- DuFour, R. (2004). What is a Professional Learning Community?.Educational Leadership, 61(8), 6-11.

- Eller, L. S., Lev, E. L., & Feurer, A. (2014). Key components of an effective mentoring relationship: a qualitative study. Nurse Education Today, 34(5), 815–820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.07.020

- Feiman-Nemser, S., & Parker, M. B. (1992). Mentoring in context: A comparison of two U.S. programs for beginning teachers. Michigan, MI: Michigan State University, National Centre for Research on Teacher Learning (NCRTL).

- Feiman-Nemser, S., & Parker, M. B. (1992). Mentoring in context: A comparison of two U.S. programs for beginning teachers. Michigan, MI: Michigan State University, National Centre for Research on Teacher Learning (NCRTL). Retrieved from http://ncrtl.msu.edu/http/sreports/spring92.pdf

- Fullan, M. (2001). The New Meaning of Educational Change (Third Edition). Columbia University, New York and London: Teachers College Press.

- Garvin, A. D. (1993). Building a Learning Organization. Harvard Business Review, 71(4), 78-91. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/1993/07/building-a-learning-organization

- Garvin, D. A. (2003). Learning in Action: A Guide in Putting the Learning Organization to Work. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Harris, A., & Jones, M. (2010). Professional learning communities and system improvement. Improving Schools, 13(2), 172-181. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480210376487

- Kools, M., & Stoll, L. (2016). What makes a school a learning organization? Education Working Paper. Paris: OECD Publishing. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/education/school/school-learning-organisation.pdf

- Leidenfrost, B., Strassnig, B., Schütz, M., Carbon, C., & Schabmann, A. (2014). The Impact of Peer Mentoring on Mentee Academic Performance: Is Any Mentoring Style Better than No Mentoring at All. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 26(1), 102-111.

- Lieberman, A., & Miller, L. (Eds.) (2008). Teachers in professional communities: Improving teaching and learning. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Louis, K. S., & Kruse, S. D. (1995). Professionalism and community: Perspectives on reforming urban schools. Thousand Oaks, California: Corwin Press.

- Marsick, V. J., & Watkins, K. E. (1999). Facilitating learning organizations: Making learning count. Aldershot: Gower.

- Marsick, V. J., & Watkins, K. E. (2003a). Making Learning Count! Diagnosing the Learning Culture in Organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication.

- Marsick, V. J., & Watkins, K. E. (2003b). Demonstrating the Value of an Organization's Learning Culture: The Dimensions of the Learning Organization Questionnaire. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 5(2), 132-151.

- OECD (2018). Developing Schools as Learning Organisations in Wales. Paris: OECD Publishing. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/education/Developing-Schools-as-Learning-Organisations-in-Wales-Highlights.pdf

- Pedler, M. B. J., & Boydell, T. (1996). The Learning Company. A strategy for sustainable development. London: McGraw-Hill.

- Redding, J. (1997). Hardwiring the learning organization. Training and Development, 51(8), 61-67.

- Schlecty, P. C. (1997). Inventing Better Schools. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Schön, D. A. (1973) Beyond the Stable State. Public and private learning in a changing society, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Senge, P. (1990). The Fifth Discipline: the Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Doubleday.

- Senge, P. (1996). Leading Learning Organizations. Training & Development, 50(12), 36-44.

- Senge, P., Kleiner, A., Roberts, C., Ross, R. B., & Smith, B. (1994). The fifth discipline fieldbook. Strategies and tools for building a learning organization. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

- Senge, P., Kleiner, A., Roberts, C., Ross, R. D., & Smith, B. J. (2000). Schools that learn: The fifth discipline fieldbook for educators, parents, and everyone who cares about education. New York: Doubleday.

- Senge, P., Kleiner, A., Roberts, C., Roth, G., & Smith, B. (1999). The dance of change. The challenges of sustaining momentum in learning organizations. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

- Wang, J., & Odell, S. J. (2002). Mentored learning to teach according to standardsbased reform: a critical review. Review of Educational Research, 72(3), 481–546. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543072003481

- Watkins, K. E., & Marsick, V. J. (1997). Dimensions of the Learning Organization Questionnaire. Warwick: Partners for the Learning and Leadership.

- Williams, R. B., Brien, K., & LeBlanc, J. (2012). Transforming Schools Into Learning Organizations: Supports and Barriers to Educational Reform. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 134(13). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ996773.pdf

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

17 June 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-084-6

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

85

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-814

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Bradea, A., & Blândul, V. C. (2020). The Role Of Mentoring In The Context Of Learning Organizations. In V. Chis (Ed.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2019, vol 85. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 68-77). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.06.7