Abstract

The term "Jewish Holocaust" relates to the murder of six million Jews by the Nazis in Europe during World War II. This paper presents significant results regarding the evolution of Israeli high-school students' attitudes towards post-Holocaust moral dilemmas faced by the Jewish people after the Holocaust. The aim of this research was to test whether a Holocaust Learning Program generated changes in the participant's moral attitudes. 102 participants – male and female students in three Israeli high-schools, answered a Moral Attitudes Questionnaire, administered at three points of time over a period of a one-year Holocaust Learning Program at school. The results revealed that the evolution of the participants' moral attitudes towards Post-Holocaust era moral dilemmas only demonstrated significant change for category 5a - "Consideration of revenge and compromise", where their agreement with the affective-intuitive moral solution decreased significantly, and for category 6a -"The perception of the Holocaust as a historical event", where their agreement with the Universal moral solution decreased significantly. One of the main conclusions is that continuous learning and deeper understanding of the Holocaust, through learning, led participants to become more emotionally involved but they also acquired more understanding of the complexity and difficulty involved in making moral decisions in the reality of the Holocaust. This combination of factors led to a greater understanding and acceptance of the way that Jewish people coped with the horror and moral challenges of the Holocaust.

Keywords: Moral dilemmasmoral attitudesjudgement and acceptance

Introduction

The Second World War (1939-1945) is considered one of the most important and influential historic events for humanity in the twentieth century and possibly the most terrible of all. One of the darkest episodes of this war and probably the most despicable of all is the genocide suffered by the Jews in Europe during War World II - the Holocaust: this involved the systematic murder of six million Jews by the Nazis under the leadership and vision of their leader, the Fuhrer, Adolph Hitler (Barley, 2007).

The Jewish Holocaust was an enormous national trauma and human tragedy that shook the very foundations of the Jewish people all over the world. The Holocaust ended on May 9th 1945 with the Nazi Germany’s surrender, but its results and implications are always present and without a shadow of doubt, will continue to influence and occupy Jews and Jewish Israelis for many generations to come (Greif, Weitz, & Machman, 1983). This explains why from the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, the Holocaust has been seen by the Jews in the diaspora and by Israelis as a fundamental event that has defined the nature of Israeli society, discourse and education at different levels. The Holocaust has also had a major influence on the Israeli education system, although its content and appearance in this system has altered over time (Machman, 1998).

Israelis experience the subject of the Holocaust in many ways from early childhood, especially in school, therefore the issue of Holocaust in Israel is an important unifying element, a part of the national ethos and held in consensus by all parts of Israeli Jewish society (Gottwein, 1998). An excellent explanation of these processes and above all the educational aspect was given by Barnea (2014):

The Holocaust can remind us that Israel is also the means to protect against any future attempt to obliterate the Jewish people in its entirety. The Holocaust can teach us that there are sane people and developed cultures who are liable to enlist to perform genocide and that allowing the slaughter of those distant from them will eventually allow the slaughter of their own relatives. The Holocaust can teach us the power of resistance that exists in a normal person's soul, a power that they themselves could not imagine. We must learn not only in order that others should know, we must learn despite the pain. That pain is less than the suffering that may be the fate of the Jewish people and humanity if we forget. (p. 27)

Over the years, systematic continuous and large scope efforts have been invested to broaden and improve Holocaust teaching in Israel’s school system. The goals of Holocaust teaching have become more complex and more sophisticated. If in earlier years the main goal was to commemorate the victims and to learn the history, today the goals have become broader and also include educational messages relating to Jewish and Israeli identity, democracy, values, and ideology (Lev, 2007; Lev, Shadmi, & Ben-Ezra, 2006).

However, public and academic discourse in Israel usually tends to ignore ethical issues and dilemmas relating to the Jews’ behavior, mostly during but also after the Holocaust (Weinrab, 1984; Aharonson, 1999). This is not surprising since dealing with issues such as these can be considered as picking at a very deep, still open wound (Efrat & Baban, 2016).

The main goal of this paper was to test whether a Holocaust Learning Program at school generated changes in the attitudes of Israeli high-school students towards post-Holocaust moral dilemmas faced by the Jewish people.

Problem Statement

Previous research regarding Holocaust implications has not related to the complex issue of the attitudes of Israeli high-school students towards moral dilemmas faced by the Jewish people in the post-Holocaust era and the potential effect that a Holocaust learning program may have on the evolution of these attitudes.

Research Questions

The research question was: Did the Holocaust Learning Program generate changes in the participants' moral attitudes towards post-Holocaust moral dilemmas?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether the Holocaust Learning Program generated changes in the participant's moral attitudes towards post-Holocaust moral dilemmas.

Research Methods

Participants

The research population included 102 male and female participants - Israeli high school students aged 17-18 from three different high schools in north Israel, who all volunteered to participate in the research. They were members of the third and fourth generation after the Holocaust, however, not all of them had relatives who were Holocaust victims or survivors.

Procedure

The research took place over a period of two academic years: from January 2015 (when the students were in the middle of Grade 11) until January 2016 (when they were in the middle of Grade 12). The research process included measurement of attitudes through the administration at three points in time during this period of a Moral Attitudes Questionnaire which included seven Holocaust moral dilemmas: Measurement 1 took place when the students were in the middle of Grade 11 in January 2015. At this time, they began their formal learning process for matriculation exams in Jewish Holocaust history and began their preparation for the journey to visit Holocaust memorial sites in Poland. Measurement 2 took place after the students returned from the journey to Poland in September 2015 at the beginning of Grade 12. Measurement 3 took place in January 2016 in the middle of Grade 12. At this time, the students completed their matriculation exams in Holocaust studies.

The research tool

The tool used in this study is a specially developed closed-ended questionnaire investigating the participant's moral attitudes towards post-Holocaust moral dilemmas. The questionnaire drew upon the pioneering work of Kohlberg (1973) and many of his followers for example: Foot (1967) and Graham et al. (2011). It presents seven main moral dilemmas that faced Jews after the Holocaust (1945-2016). These seven dilemmas were chosen because of the fact that they are especially noteworthy in a comprehensive review of the relevant literature regarding post-Holocaust era. Each dilemma is followed by two alternative moral solutions. All the dilemmas and all the solutions provided are historically authentic. Participants were requested to indicate their personal attitude concerning the two suggested different solutions, A or B, for each dilemma on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 = strongly disagree, and 5= strongly agree. They could choose to relate to one solution (A or B), or to both solutions, A+B. Alternatively, they could mark the response “I have no opinion” or write a solution of their own.

Data analysis

This included inferential statistics for the entire population of participants and was performed by "Repeated Measures", deductive statistical analysis using ANOVA tests and Bonferroni t-tests. This type of analysis was used in order to examine whether there was a significant statistical difference in the evolution of the participants' moral attitudes between one point of time and the next. The measurements were conducted at the three points in time for each participant’s attitudes towards each moral dilemma, so that a comparison could be performed between the measurements of each and every one of the participants. For further analysis the seven dilemmas were sorted into three categories according to similar characteristics.

Research limitations

This was an exploratory research, which as far as we could ascertain was the first study on the subject of Israeli high school students' perceptions over their moral attitudes towards Holocaust moral dilemmas. Therefore, there were no other results from similar research studies that we could compare with our results. This limitation could be overcome by further research on this issue.

Findings

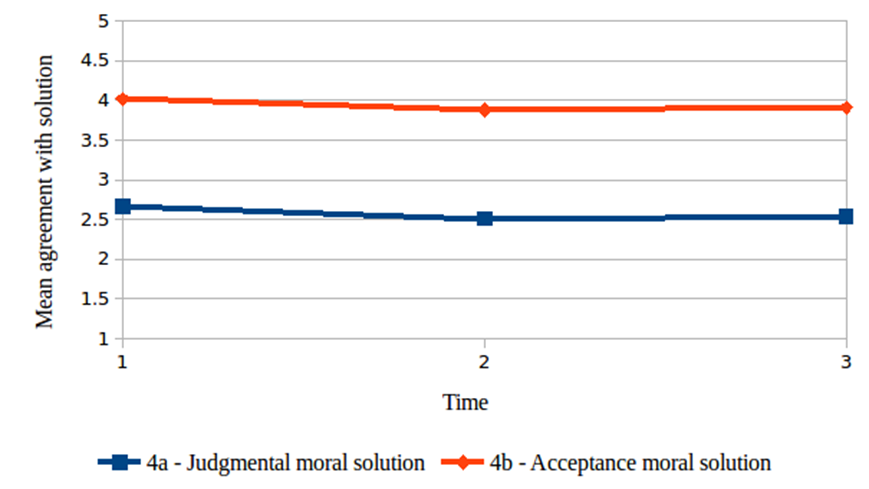

Category 4 - "The perception of Jewish behavior towards the Nazis": including the 'Like Lambs to the slaughter dilemma', the 'Kapo dilemma', the 'Kastner dilemma' and the 'Resistance dilemma'. The main common characteristic of this category is the attempt to understand and evaluate the way that Jews behaved towards the Nazis from different perspectives. Moral deliberation for this category exists between “judgmental” versus “acceptance” moral attitudes. Means and SDs for grades given by the respondents for this category at three time points appear in Table

The results shown in Figure

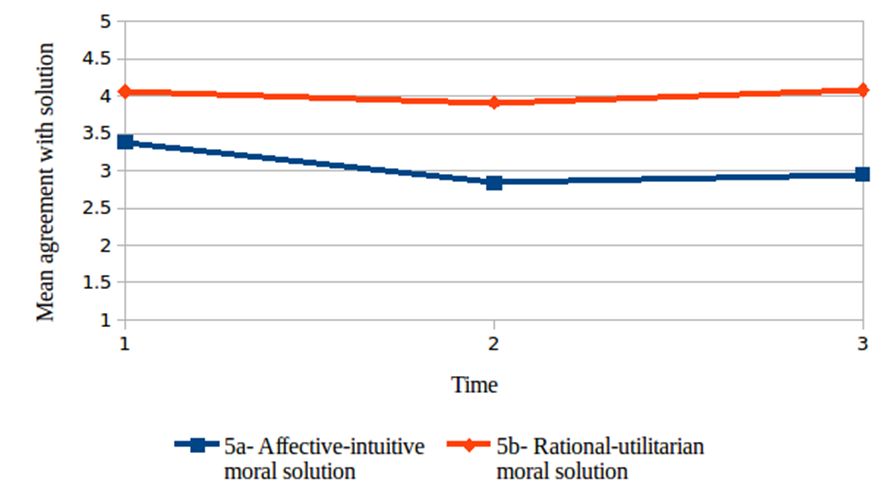

Category 5 – "Consideration of revenge and compromise": including the 'Revengers dilemma' and the 'Restitution Payments dilemma'. The main common characteristic of this category is Jewish thinking and decisions concerning the way in which to treat the crimes of former Nazis in the post-Holocaust era. Moral deliberation exists between "affective-intuitive” versus “rational-utilitarian” moral solutions. Means SDs for grades given by the respondents for this category at three time points appear in Table

Figure

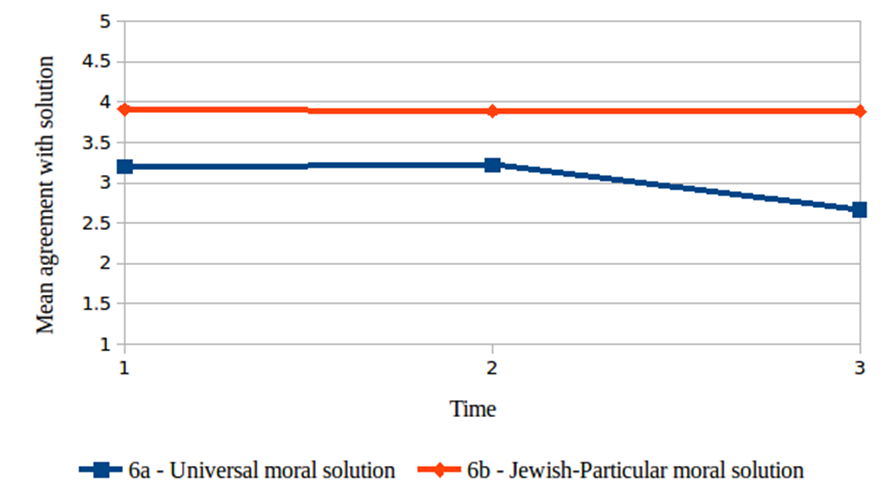

Category 6 – "The Perception of the Holocaust as a historical event": including the 'Comparison of the Holocaust dilemma'. The essence of the dilemma is whether or not to compare the Jewish Holocaust to other genocides in history. Moral deliberation exists between “universal” versus “Jewish-particular” moral solutions. Means and SDs for grades given by the respondents for this category at three time points appear in Table

The results shown in Figure

In order to address the question whether there were significant differences in the evolution of Holocaust-era moral attitudes between the different stages of learning, a comparison was drawn between the changes at the different stages. Table

It can be summarized that the evolution of the participants’ attitudes towards Post-Holocaust era moral dilemmas demonstrates significant change only for category 5a - "Consideration of revenge and compromise", where the participants' agreement with the affective-intuitive moral solution decreased significantly, and for Category 6a -"The perception of the Holocaust as a historical event", where the agreement with the Universal moral solution decreased significantly.

Conclusion

In Category 4 - "the perception of Jewish behavior towards the Nazis", the results revealed an increase in the level of agreement with the 'acceptance moral solution' regarding the way that Jews behaved towards the Nazis’ oppression and murderous actions during the Holocaust. Yet this trend was reduced by the strong deliberation that existed in this category. One explanation for this result is the complicated structure and components of the dilemmas in this category. This interpretation is supported by Moll and de Oliveira-Souza (2007) who claimed that insofar as the dilemma is more realistic and clearer, the examinee’s ability to make a decision will increase and vice versa. In relation to this research it seems that the learning process helped the participants to clarify the issues involved and make up their minds regarding the dilemmas. Another explanation relates to the emotional aspect. Guglielmo, Monroe, and Malle (2009) explained that emotions have a significant if not decisive influence on thinking and especially on moral decisions concerning moral dilemmas. This explanation fits our results since the participants demonstrated serious deliberation concerning the heavily emotional nature of the dilemmas to which they were asked to react. Nevertheless, the participants demonstrated that their learning helped them to define their attitudes more clearly and this is in line with the findings of Greene (2011), who claimed that when the examinees are more emotionally involved in the dilemma their ability to make clearer moral decisions will increase, although they are more influenced by the emotional aspect. The conclusion is that continuous learning and deeper understanding of the dilemmas led participants to become more emotionally involved but they also acquired more understanding of the complexity and difficulty involved in making moral decisions and especially regarding moral behavior in the reality of the Holocaust. This combination of factors led the participants to greater understanding and acceptance of the way that Jewish people coped with the horror and moral challenges of the Holocaust.

In Category 5- "consideration of revenge and compromise", the results indicate that there was an increase in the level of agreement with the 'rational-utilitarian moral solution' concerning the way to treat Nazi crimes after the Holocaust. This means that there was support for the normalization of relationships between the Jewish people, the State of Israel, Germany and the German people after the Holocaust, and this was accepted by the participants as the more correct moral attitude despite strong bitter feelings that still seem to exist. This attitude is of course affected by the financial and other benefits of normalization. Our results are supported by Greene and Haidt (2002), who noted that there may be a substantial difference between moral consideration and a moral decision. There are cases in which examinees will think in one direction, but make a decision in another direction. This is primarily influenced by the balance between personal utilitarian factors versus the principled moral factor. More reinforcement for this interpretation is given by the findings of Haidt and Joseph (2007). They claimed that intuition is an important factor in moral decision-making although it is possible that later, when explaining their cognitive considerations for the making of the decision, actors will not provide sufficient consideration for this element. The conclusion is that continuous learning and deeper understanding of the dilemmas will weaken or at least moderate the initial emotional response and then the individual will adopt more rational-utilitarian moral attitudes.

In Category 6- "the perception of the Holocaust as a historical event", the results revealed an increase in the level of agreement with the 'Jewish-particular moral solution' which apprehends the Holocaust as a unique "Jewish only" event which cannot be compared to other genocides. It seems that at the beginning of the learning, the first or perhaps the intuitive attitude of the participants was to also support the 'universal moral solution' which understands the Holocaust as one of many worldwide terrible phenomena – genocides. However later on, this approach was weakened by the effect of learning and educational emphases. This is no surprise in light of the strong tendency in Israeli society and education to think of the Holocaust as a unique "Jewish only" event that cannot be compared to anything else (Oron, 2006). This interpretation is strengthened by the claim of Haidt and Joseph (2007) that intuition is an important factor in moral decision-making, although it is possible that later, when explaining the cognitive considerations for the making of the decision, people will not provide sufficient consideration for this element. Reinforcement for this claim was presented by Aquino and Reed, (2002), who found that personal states and specific circumstances will have significant influence both on an individual’s moral judgment and also on their moral decision-making. The conclusion is that the participants in our research changed or at least moderated their earlier support for the 'universal moral solution' and subsequently gave more support for the 'Jewish-particular moral solution', as a result of educational direction and guidance during the learning process which emphasized this line of thinking.

References

- Aharonson, M. (1999). Memory as history and history as memory. Israel: Ramat Gan Museum.

- Aquino, K., & Reed, A. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1423-1440.

- Barley, M. (2007). The third Reich, a new history. Tel Aviv: Zemora-Bitan and Yavne Publisher.

- Barnea, A. (2014). Why remember? Mizkar. Journal for Holocaust Matters, Uprising, Memory and Memorial, 42, 27. [in Hebrew]

- Efrat, S., & Baban, A. (2016). Holocaust moral attitudes among Israeli high school students, In K. A. Moore, P. Buchwald, F. Nasser-Abu Alhija, & M. Israelashvili, (Eds), Stress and Anxiety, Strategies, Opportunities and Adaptation (pp. 93-100). Berlin: Logos, Verlag.

- Foot, P. (1967). The problem of abortion and the doctrine of double effect. Oxford Review, 5, 5–15.

- Gottwein, D. (1998). Privatization of the Holocaust: Politics, memory and historiography, Pages for the research of the Holocaust. Collection 15, Institute for the Research of the Holocaust Period. University of Haifa and Ghetto Fighters House Publications. [in Hebrew]

- Graham, J., Iyer, R., Nosek A. B., Haidt, J., Koleva S., & Ditto H. P. (2011), Mapping the moral domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 366–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021847

- Greene, J. D. (2011). Emotion and morality: A tasting menu. Emotion Review, 3(3), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1754073911409629

- Greene, J. D., & Haidt, J. (2002). How (and where) does moral judgment work? Trends in Cognitive Science, 6, 517-523.

- Greif, G., Weitz, Y., & Machman, D. (1983). In the days of the holocaust. Units 1-2. Jerusalem: Open University. [in Hebrew]

- Guglielmo, S., Monroe, A. E., & Malle, B. F. (2009). At the heart of morality lies folk psychology. Inquiry, 52, 449–466.

- Haidt, J., & Joseph, C. (2007). The moral mind: How 5 sets of innate intuitions guide the development of many culture-specific virtues, and perhaps even modules. The Innate Mind, 3, 367–391.

- Kohlberg, L. (1973). The claim to moral adequacy of a highest stage of moral judgment. Journal of Philosophy, 70(18), 630–646.

- Lev, M. (2007). Teenagers travel into memory. In M. Shmida & S. Romi (Eds.), Education in formal reality changes (pp. 219-239). Jerusalem: Magnes Press – Hebrew University.

- Lev, M., Shadmi, H., & Ben-Ezra, J. (2006). A journey of a man following people. Israel: Ministry of Education, Psychological-Counseling Services in cooperation with the Director of Social Education. [In Hebrew]

- Machman, D. (1998). The Holocaust and its research – Conceptualization, terminology and fundamental issues. Tel Aviv: The Mordechai Anilevitch House of Testimony. [in Hebrew]

- Moll, J., & de Oliveira-Souza, R. (2007). Moral judgments, emotions and the utilitarian brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 319–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2007.06.001

- Oron, Y. (2006). Genocide – Thoughts on the unimaginable, theoretical aspects of the study of genocide. Tel Aviv: The Open University. [Hebrew]

- Weinrab, A. (1984). Three days we walked. Tel Aviv: Ghetto Fighters House and Kibbutz Hameuhad. [in Hebrew]

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

17 June 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-084-6

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

85

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-814

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Efrat, S., Pintea, S., & Baban, A. (2020). The Evolution Of Moral Atitudes Towards Post Holocaust Moral Dilemmas. In V. Chis (Ed.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2019, vol 85. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 606-615). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.06.62