Abstract

Six million Jews were systematically murdered by the Nazis during World War II. This is known as the Jewish Holocaust. The Israeli Ministry of Education began to teach the issue of Holocaust in the early 1950s and continues to do so until today. This paper presents significant results regarding the evolution of Israeli high-school students' moral attitudes towards different strategies employed by Jews to cope with moral dilemmas that occurred during the Holocaust. The aim of this research was to test whether a Holocaust Learning Program generated changes in the participant's moral attitudes. 102 male and female students in three Israeli high-schools, responded to a Moral Attitudes Questionnaire over three research stages at three points of time during their studies in the Holocaust Learning Program at school. The results revealed that in the evolution of participants' moral attitudes towards Holocaust era dilemmas there was a non-significant increase in the level of participants’ agreement with survival moral solutions and a significant decrease in the level of their agreement with deontological moral solutions in all three dilemmas categories. These results lead to two initial conclusions: the first conclusion is that the learning process is the main cause for these developments. The second conclusion is that it is easier to decrease the level of agreement with deontological moral solutions than to increase the level of agreement with survival moral solutions.

Keywords: Moral dilemmasmoral attitudesmoral solutions

Introduction

Since the destruction of Jerusalem and the deportation of most of the Jewish people from ancient Israel by the Roman Empire in 73AD, there have been two further events that are seen by scholars as exceptional historical events in the history of the Jewish people. These events, or perhaps historical processes are the Jewish Holocaust that occurred from 1939-1945 during the Second World War and the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 (Gutman, 1983). The proximity of these two events is not random and there is a close affinity between them, although each holds a significant status of its own. From a chronological viewpoint, the establishment of the State of Israel occurred after the Holocaust and the Holocaust served as an important catalyst in the establishment of the new state. Therefore, it is not surprising that the Israeli Ministry of Education relates to this connection in its learning program and introduces the chapter on the establishment of the state immediately after the chapter on the Holocaust in its history textbooks (Guterman, Yablonka, & Shalev, 2008).

Although the Holocaust ended with the surrender of Nazi Germany on 9th May 1945, it continues to influence and occupy the Jewish people and the State of Israel in various educational, social, and cultural dimensions until today (Weitz, 1997). Thus too, the official establishment of the State of Israel on 14th May 1948, just three years after the end of the Holocaust, is a process that in a way has not ended until today. This is at least true in geo-political terms since the young state is under constant existential threat from some of its neighbor states (Klausner, 1975; Goren, 1997).

In order to discuss the issues raised by the Holocaust in the context of the State of Israel, it is necessary to understand how these issues are seen in Jewish and Israeli perceptions. In a broad national-historical conceptualization, the predominant Jewish view sees the Holocaust as an additional event along the sequence of continuous attempts by different empires, peoples and dictators to harm and destroy the Jewish people and now also the State of Israel. This orientation traces the persecution of the Jews from the times of the Assyrians and Babylonians, through the Persians and Greeks and the Romans, to the Spanish Inquisition, the "pogroms" that massacred Jews in Eastern Europe and of course the Holocaust perpetrated by German Nazis and their collaborators among the European nations. The modern-day aspirations of some states and terror organizations to destroy the State of Israel is seen by most Jews and Israelis as simply a current stage in this continuous process (Machman, 1996b).

The difficult events of the Holocaust, which were experienced to a different extent and at different strengths by the survivors` children through the medium of their parents, never disappeared and is continually influential (Bar-On, 1994). These influences continue to resonate over their children and grandchildren.

From the early days of the State of Israel, the Holocaust was seen as a fundamental event that defined Israeli society at different levels and consequently influenced the Israeli education system, although its appearance and content altered over the years (Machman, 1998). Machman (1998) notes:

“It is impossible for the subject of the Holocaust not to be mentioned at one stage or another of the education process” (p. 687).

For this reason, Israeli schools and the Ministry of Education began to deal with the teaching of the issue of the Holocaust in the early 1950s and continue to do so until today.

The main aim of this paper was to test whether a Holocaust Learning Program at school generated changes in the attitudes of Israeli high-school students towards Holocaust moral dilemmas faced by the Jewish people during the Holocaust.

Problem Statement

Previous research has not considered the complex issue of Israeli high-school students' attitudes towards moral dilemmas faced by the Jewish people in the Holocaust and the potential effect that a Holocaust learning program may have on the evolution of these attitudes.

Research Questions

The research question: Did the Holocaust Learning Program generate changes in the participants' moral attitudes towards the moral dilemmas of Jews in the Holocaust?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to test whether the Holocaust Learning Program could generate changes in the participant's moral attitudes towards the Jews' moral dilemmas during the Holocaust.

Research Methods

Participants. One hundred and two male and female high school students participated in the study. Their ages ranged from 17-18 and they were studying in three different high schools in Israel. All of them volunteered to participate in the research. They all belong to the third and fourth generation after the Holocaust, but not all of them have relatives who are Holocaust survivors or victims.

Procedure. The research was conducted over two academic years from January 2015, when the students were in the middle of Grade 11 and until January 2016 when they were in the middle of Grade 12. The research instrument was a Moral Attitudes Questionnaire which contained statements describing seven Holocaust moral dilemmas. The questionnaire was administered at three points in time during the research period: Measurement 1 took place when the students were in the middle of Grade 11 in January 2015, at the beginning of the formal learning process for matriculation exams in Jewish Holocaust history and when they were preparing for a journey to visit Holocaust memorial sites in Poland. Measurement 2 took place after the students returned from the journey to Poland in September 2015, at the beginning of Grade 12. Measurement 3 took place in January 2016 in the middle of Grade 12, when the students completed their matriculation exams in Holocaust studies.

The research tool used in this study is a specially developed closed-ended questionnaire investigating the participant's moral attitudes towards Holocaust era moral dilemmas. The questionnaire was developed on the basis of pioneering work by Kohlberg (1973) and his followers for example: Foot (1967) and Graham et al. (2011). The questionnaire presents seven main moral dilemmas that faced Jews during the Holocaust (1939-1945). These dilemmas were chosen because they stand out after comprehensive review of the relevant literature regarding the Holocaust era. Two alternative solutions are given for each dilemma – a deontological moral based solution as opposed to a survival moral based solution. All the dilemmas and solutions are historically authentic. Participants were requested to indicate their personal attitude concerning the two different suggested solutions, A or B, for each dilemma on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 = strongly disagree, and 5= strongly agree. They could choose to relate to one solution (A or B), or to both solutions, A+B. Alternatively, they could mark the response “I have no opinion” or write a solution of their own

Data analysis including inferential statistics for the data from all participants was performed by "Repeated Measures" deductive statistical analysis using ANOVA tests and Bonferroni t-tests. This type of analysis was used to examine whether there was a significant statistical difference in the evolution of the moral attitudes between one point of time and the next. The measurements were conducted at the three points in time for each participant’s attitudes towards each moral dilemma, so that a comparison could be performed between the measurements of each and every one of the participants. For further analysis, the seven dilemmas were classified into three categories according to similar characteristics.

Research limitations. This was an exploratory research, which as far as we could ascertain was the first study on the subject of Israeli high school students' moral attitudes towards Holocaust moral dilemmas. Therefore, there were no other results from similar research studies that could be compared with our results. This limitation could be overcome by further research on this issue.

Findings

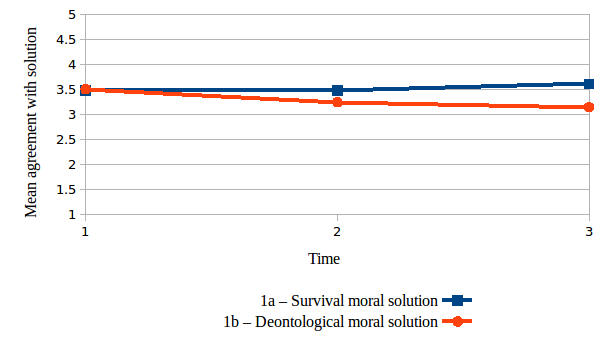

Category 1 - "The collaboration dilemmas": including the 'Judenratt dilemma', the 'Sonderkommando dilemma' and the 'Rebels dilemma'. Moral deliberation exists between deontological and survival moral solutions. The main common characteristic of this category is the influence of the individual’s decision on the wide circle of his community. These are "Collaboration" dilemmas" because the question, whether to collaborate with the Nazis or not, is the core of the different dilemmas in this category. Means and SDs for grades given by the respondents for this category at three time points appear in Table

The results shown in Figure

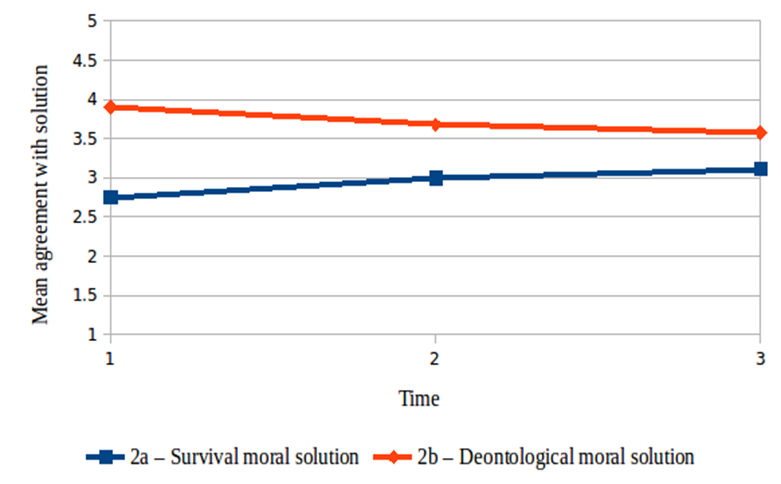

Category 2 - "The acute dilemmas": including the 'Crying baby dilemma' and the 'Thief’s dilemma'. Moral deliberation exists between deontological morality and survival morality. The main common characteristic of this category is the direct influence of the individual’s decision on a specific other individual within a very close social circle - his family or a small group of Jews in hiding in the 'crying baby dilemma' and the group of prisoners in the extermination camp in the 'thief's dilemma'. These dilemmas are defined as "acute dilemmas" because the individual needs to make a fast decision with no way back. Means and SDs for grades given by the respondents for this category at three time points appear in Table

The results shown in Figure

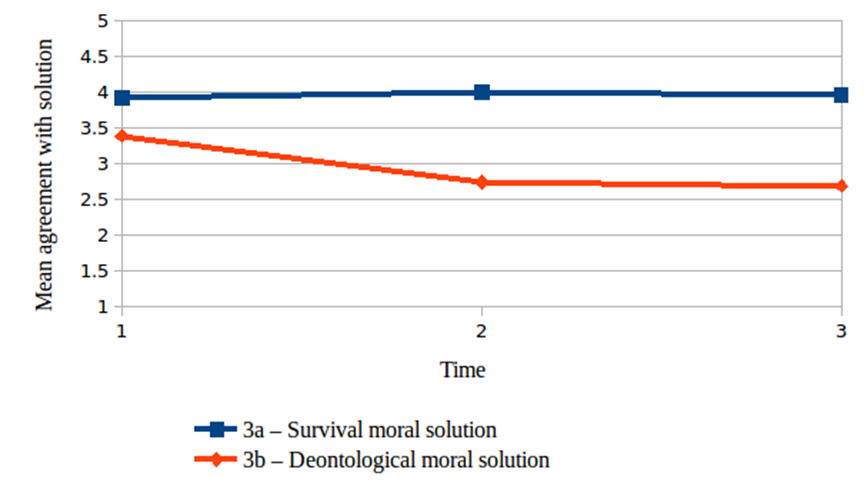

Category 3 - "The parental dilemmas": including the 'Little Smuggler dilemma' and the 'Giving children away dilemma'. Moral deliberation exists between deontological morality and survival morality. The main common characteristic of this category is the direct influence of the individual – the parent’s decision on the fate of his child or children. Means and SDs for grades given by the respondents for this category at three time points appear in Table

The results as shown in Figure

In order to address the question whether there are significant differences in the evolution of Holocaust-era moral attitudes between the different stages of learning, a comparison was drawn between the changes at the different stages. Table

In conclusion, it seems overall that the learning process regarding Holocaust era dilemmas led to insignificant increase in the level of the participants’ agreement with survival moral solutions and a significant decrease in the level of their agreement with deontological moral solutions.

Conclusion

The research aimed to test whether the Holocaust Learning Program generated changes in the participant's moral attitudes. General observation of the results indicates that the evolution of moral attitudes concerning Holocaust-era dilemmas demonstrates a non-significant increase in the level of participants’ agreement with survival moral solutions and a significant decrease in the level of their agreement with deontological moral solutions in all three categories. This result leads to the two initial conclusions: the first conclusion is that the learning process is the main cause for this evolution. The second conclusion is that it is easier to decrease the level of agreement with deontological moral solutions than to increase the level of agreement with survival moral solutions. However, when we look closely at the different dilemmas’ categories, we find differences. The described trend of increasing agreement with survival moral solutions and decreasing agreement with deontological solutions forms a hierarchy which is maintained throughout the whole learning process: it was most difficult to agree with the survival moral solution and easiest to agree with the deontological moral solutions primarily in Category 2 - the 'acute dilemmas' in which an individual decides to take personal direct action, killing another person in order to save his own life. This was less true in Category 1 –the 'collaboration dilemmas' where an individual’s moral decision influences the fate of many people but less directly, and least true in Category 3 –the 'parental dilemmas' where the individual’s moral decision involves the consideration of a chance to rescue his children, although this involved high risk of harm to the child.

The difference between the three categories can be explained by the nature of the dilemmas. As mentioned before all Holocaust era dilemmas are “harm to save” (H2S) dilemmas, where one must decide whether to hurt another person in order to save more or other lives (Koenigs et al., 2007). In this context, the dilemmas of Category 2 and especially the 'Crying baby' dilemma are the most extreme and hard to cope with. The reasons are mainly the direct and immediate connection between the action and the outcome and the personal connection between the killer and the victim. This interpretation is supported by the findings of Gillath, McCall, Shaver, and Blascovich (2008), which indicated that dilemmas relating to physical injury and especially killing of humans are more meaningful and arouse stronger emotional reactions. Furthermore, an interesting process was also observed with regard to the gap or the difference between the contradicting moral solutions in the three categories: insofar as the level of agreement with the survival solution is at its lowest at the beginning of the learning, then the increase in level of agreement with this solution is highest over time. Simultaneously insofar as the agreement with the deontological solution is highest at the beginning of the learning, then the decrease in the level of agreement with this solution is lowest over time.

The third conclusion is that we can arrange the three Holocaust era dilemmas’ categories (1, 2 and 3), which have the same kind of moral decision mechanism (deontological versus survival) according to level of difficulty and the extent of the change in the level of agreement.

The fourth conclusion is that the acquisition of knowledge through learning gradually changes the participant's moral attitudes. It increases the level of agreement with survival moral solutions and decreases the level of agreement with deontological solutions. The reason for this evolution is that participants acquire greater cognitive understanding and emotional acceptance of the unique reality of the Holocaust era moral dilemmas through the learning process.

At the end of this discussion we are now able to compare the findings regarding attitudes towards the dilemmas from the Holocaust era to previous research concerning moral dilemmas. As observed, traditional theories of moral development emphasize the role of controlled cognition in mature moral judgment, while a more recent trend emphasizes intuitive and emotional processes. In the course of time a dual-process theory synthesizing these perspectives has also developed. This theory associates utilitarian moral judgment (approving harmful actions that maximize good consequences) with controlled cognitive processes and associated non-utilitarian moral judgment. The theory suggests that cognitive load manipulation selectively interferes with utilitarian judgment. This interference provides direct evidence for the influence of controlled cognitive processes in moral judgment and more specifically in utilitarian moral judgment (Greene, Morelli, Lowenberg, Nystrom, & Cohen, 2007). As has been observed in reliance on this theory, in this research the initial attitudes of the participants towards Holocaust era dilemmas tended toward deontological moral solutions, which have much emotional impact (but also involve much deliberation). Then, over the learning process, their attitudes tended to move more towards the survival (utilitarian), solutions that are influenced more by cognitive processes.

The fifth conclusion therefore is that the process of learning about Holocaust moral dilemmas reinforced and strengthened the cognitive adoption of moral attitudes which justify harmful actions that maximize good in an extreme situation involving a threat to life. Based on the understanding that a moral attitude involves both emotional and cognitive components we can draw another conclusion from a wider perspective.

The sixth conclusion is that the participants’ initial intuitive reaction to moral dilemmas (especially Holocaust like moral dilemmas) is mostly emotional and this reaction leads to more agreement with deontological moral solutions. However, later during the learning process, a combination of acquired knowledge on the Holocaust dilemmas, understanding of the moral conflicts involved and development of moral thinking about different solutions over a significant period of time, moderated the participants’ initial emotional reactions. This process also balances and deepens moral thinking and eventually leads to more agreement with survival (utilitarian) moral attitudes.

References

- Bar-On, D. (1994). From fear to hope. Israel: The Ghetto Fighters House and the Kibbutz Hameuhad. [in Hebrew]

- Foot, P. (1967). The problem of abortion and the doctrine of double effect. Oxford Review, 5, 5–15.

- Gillath, O., McCall, C., Shaver, P., & Blascovich, J. (2008). What can virtual reality teach us about prosocial tendencies in real and virtual environments? Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260801906489

- Goren, Y. (1997). War of independence. Tel Aviv: Ilan Publishers. [in Hebrew]

- Graham, J., Iyer, R., Nosek, A. B., Haidt, J., Koleva, S., & Ditto, H. P. (2011). Mapping the moral domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 366–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021847

- Greene, D. J., Morelli, A. S., Lowenberg, K., Nystrom, E. L., & Cohen, D. J. (2007), Cognitive load selectively interferes with utilitarian moral judgment. Cognition, 107, 1144–1154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2007.11.004

- Guterman, B., Yablonka, H., & Shalev, A. (Eds.) (2008). We are here – Holocaust survivors in the State of Israel. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem Publications. [in Hebrew]

- Gutman, I. (1983). The Holocaust and its meaning. Jerusalem: Zalman Shazar Centre Publications. [in Hebrew]

- Klausner, I. (1975). The history of Zionism. Tel Aviv: The Zalman Shazar Centre for Israeli History. [in Hebrew]

- Koenigs, M., Young, L., Adolphs, R., Tranel, D., Cushman, F., Hauser, M., & Damasio, A. (2007). Damage to the prefrontal cortex increases utilitarian moral judgments. Nature, 446, 908–911. https://doi.org/10.10 38/nature05631

- Kohlberg, L. (1973). The claim to moral adequacy of a highest stage of moral judgment. Journal of Philosophy, 70(18), 630–646.

- Machman, D. (1996b). The Holocaust in Jewish history, awareness and interpretation. Tel Aviv: Moreshet Publications. [in Hebrew]

- Machman, D. (1998). The Holocaust and its research – Conceptualization, terminology and fundamental issues. Tel Aviv: The Mordechai Anilevitch House of Testimony. [in Hebrew]

- Weitz, Y. (1997). From vision to revision. Tel Aviv: Zalman Shazar Centre for Israel History. [in Hebrew]

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

17 June 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-084-6

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

85

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-814

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Efrat, S., Pintea, S., & Baban, A. (2020). The Evolution Of Moral Atiitudes Towards Holocaust Moral Dilemmas. In V. Chis (Ed.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2019, vol 85. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 596-605). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.06.61