Abstract

Online learning is a synonym for 21st century learning. While about 20 years ago, online courses became part of academic institutions' curriculum in general and teacher education institutions in particular, integrating an online environment into teaching internship workshops is rare. Research knowledge about this integration of environments is scarce. Online teaching internship workshops constitute the 'younger sibling' to traditional workshops and derived from technological development. Initially the online workshops sought to respond to space and time difficulties and later, its pedagogic qualities were identified for interns, taking their first steps in the teaching world. This article proposes a model combing learning environment developed by the authors following exposure to the possibilities of online instruction through rich professional experience as a facilitator in face-to-face teaching internship workshops. The model was developed for interns to derive benefits from the advantages of both in online learning and face-to-face meetings. A short review of induction program principles around the world will continue with a description of internship workshops. Learning features in an online environment and research findings on this topic will be by details of the online workshop. Thereafter, the internship workshop model combining learning environments (face-to-face and online) will be presented and its advantages to interns training process will be emphasized. These advantages will be demonstrated through interns' voices, depicting their experiences using the model. Finally, conclusions and recommendations for follow up research will be presented.

Keywords: Online learning environmentsonline internship workshop

Introduction

The following notice was written by a new teacher in a mixed teaching environment internship model: "I will be honest and write that I have a ‘love-hate' relationship with the internship workshop. On the one hand I feel that this workshop instructs, empowers, deepens, requires internal insights and independent as well as teamwork…and on the other hand, I felt that it is bothersome, exhausting, burdensome. Sometimes I felt that it was a burden for me but this feeling dissipated the moment I read the meaningful and authentic issues raised by my fellow group members … I was genuinely immersed in the cases and events and felt a strong desire to assist and try to help to the best of my ability and experience…".

This post illustrates the benefits on the one hand and difficulties and disadvantages on the other. The intern’s ability to express her feelings openly points to the process she had experienced thanks to the possibilities of an online environment.

After about a decade of facilitating teaching internship workshops in a face-to-face environment, and considering the possibilities of online instruction, it was decided to make use of this environment in order to improve the internship process by developing a model combining those two learning environments. This article describes the model and gives voice to interns about their experiences on the presented model.

The article will open with a review of the features of induction programs around the world and continue to depict the internship workshop as a key component of these programs. Later features of online learning in general and the online internship workshop in particular will be detailed.

Literature Review

Induction programs

The induction program is the link between teacher training in academic institutions and teaching as an occupation in educational institutions. Understanding the need for support and guidance has given birth, over the past twenty years, to a range of induction to teaching programs. In a review carried out about programs (Hammer-Budnaro, 2018; Nasser-Abu Alhija, Fresko, & Richenberg, 2011), it was found that there were two key components in most programs: personal mentoring (Ingersoll & Strong, 2011) and group instruction (Zilbershtrom, 2013a).Whereas induction programs around the world emphasize hastening new teachers’ professional development, reduce teacher dropout rates and successful integration of new teachers into specific schools, the Israeli program mainly emphasizes empowering new teachers and their integration into the education system. This empowerment occurs on two levels: the one through mentor teachers accompanying new teachers and the other – participation in internship workshop facilitated by a professional.

Teaching Internship Workshops

A teaching internship workshop (also called ‘Staj’) is a learning framework for fellow interns. It is implemented in teacher education institutions in parallel to their working as teachers in their induction year (Director General's Circular, 2014). The workshop provides answers to dilemmas, helps consolidate professional work patterns and provides information about assessment during the induction year and absorption in the education system.

Internship workshops are adapted to and directed at interns' needs (Zilbershtrom, 2013a). As a fertile ground for nurturing a community of educators, they invite exposure to colleagues’ experiences and contribute to developing reflective ability and consolidating educational personality (Zilbershtrom, 2013b).

Many studies have examined the significance of internship workshops (Hammer-Budnaro, 2018; Lazovsky & Zeiger, 2004; Maskit & Dickman, 2006; Rotenberg-Tadmor, 2014; Zach, Talmor, & Stein, 2016). In Maskit and Yaffe’s study (2007), 50 diaries written by interns during their internship workshop were analysed and showed contribution to motivation and a sense of partnership. Fisherman (2011), who examined the components of the internship year, testified that most participants in the study, mentioned help from the workshop in one of four areas (workshop’s contribution to lesson planning, class management, social integration, consolidating professional identity) as particularly high.

Traditionally, internship workshops are conducted face-to-face, once in two weeks. In the last decade, online workshops have developed as part of a world trend of teaching and learning through the Internet.

Learning in an Online Environment

Historically, the online environment started to serve as a place of learning with the introduction of the Internet as a significant factor in our lives (Forkosh-Baruch, Mioduser, & Nachmias, 2012). The success of teaching in this new environment derives from its advantages, which can be catalogued as didactic, motivational and practical. Didactically, an online environment realizes the constructivist approach in education (Libman, 2013) as it places learners at the center of the educational process. An active and accessible Internet search develops learners' knowledge building skills (Aflalo, 2012) and invites establishing links with additional knowledge (Yaniv, 2017). Motivationally, it was found that the online environment creates interest and curiosity, as well as taking responsibility for the learning process. Thus, it predicts development of independent learning skills (Harper, 2018).

Practically, the online environment breaks the boundaries of time and space (Hershkowitz & Kaberman, 2009; Sela, 2010) and learners can adapt their learning obligations to personal timetables (Hussein-Farraj, Barak, & Dori, 2012). This flexibility enables collaboration and knowledge exchanges with a diverse population (Peechapol, Na-Songkhla, Sujiva, & Luangsodsai, 2018; Shonfeld, Hoter, Ganayem, & Walter, 2015). Hence, there is also an economic saving of classrooms and teaching hours (Wasserman & Migdal, 2019).

Alongside enumerated benefits, the disadvantages of the online environment will be examined. Abundant time-wasting stimuli are likely to increase attention to and concentration on deficit behaviours. Indeed, many prefer to look for learning materials among professional colleagues and not to enter the infinite sea of knowledge. Therefore, to cope with the abundant stimuli, learners have to use personal skills, such as motivation and self-discipline (Drange & Roarson, 2015; Hershkowitz & Kaberman, 2009). Those whose relevant skills tend to be low are likely to experience a decline in their self-esteem and to perform less well (Bandara & Wijekularathna, 2017).

Another disadvantage is expressed on the emotional level. An online environment lacks the component of unmediated personal contact and is therefore likely to create a sense of social alienation and lack of sharing the learning load (Wasserman & Migdal, 2019). It is recommended that teachers increase their availability and conduct designated forums to meet the emotional needs of learners (Freedman & Pritzker, 2018).

The fact that an online environment is mostly conducted in writing is another disadvantage. It thus lacks intonation, facial expressions and eye contact, which limits discourse participants with regard to accurate meaning of the message. Increased use of emotional expressions or emojis (Gilat, 2013) as well as proliferated message exchanges (Shonfeld et al., 2015) help bridge the non-verbal gap.

As the benefits of online learning outweigh its disadvantages, this environment is also used in the discipline of teacher education.

Online Learning Applications in Teacher Education

Online learning is implemented already induction to teaching stage. It was found that a virtual mentoring model for new teachers contributes both to teachers and mentors. Approximately 80% of new teacher reported that receiving timely feedback affecting the ability to make changes greatly benefitted the development of their teaching skills (Stapleton, Tschida, & Cuthrell, 2017).

Social media employed in teacher training has been proven in educational-learning aspects (Carpenter, Cook, Morrison, & Sams, 2017; Luo, Smith, & Cheng, 2016). For instance, it was found that using Twitter during studies for an undergraduate degree in teaching led to a high level of autonomous social learning (Luo & Franklin, 2012). Not only did learners show motivation in exploiting social media, they even developed a high level of independent learning and self-discipline by using this social tool for study.

One type of learning that an online environment both benefits and challenges, is experiential learning in a workshop framework.

Teaching Internship Workshop in an Online Environment

Online internship workshops were developed with technological advancement and a desire to respond to objective problems of distance and availability (Peled & Pieterse, 2013; Sela, 2010). The assumption is that profound and intelligent writing about personal and professional experiences, their processing both personally and in a group and anchoring them in theory, is considered to be equal to face-to-face learning.

The literature acknowledges the therapeutic value of writing as inviting introspection, expression of feelings and generating insights (Boniel-Nissim, 2010; Gilat, 2013) as well as leading to a decreased sense of distress (Barak & Boniel-Nissim, 2011; Kupferberg, 2013). Writing on a forum resembles an intra-personal discourse through which a person's inner voice is exposed to both writer and reader (Dickman, 2005). Hence its contribution to all participants. Furthermore, writers do not need to provide rapid, spontaneous responses (Gilat, 2013), and he/she is free to phrase responses clearly and coherently.

Contrary to classroom discussions, where only some participants lead and actively participate, in online workshops, participation is active. All participants express themselves personally, their reactions are written saved. From an emotional point of view, every reaction of a learning colleague that encourages, enlightens or reinforces, is likely to increase motivation to participate in the common learning voyage (Sela, 2010), share the burden and experience a climate of acceptance and partnership.

From an intellectual point of view, when learners are asked to explain their motives, to examine their conduct during an event through colleagues, multi-dimensional learning occurs - interns see things from other perspectives and at the same time have an opportunity to examine their views, meanings and implications. Hence, they develop problem-solving skills as well as reflective abilities (Lotan & Shimoni, 2005; Sela, 2010).

Pieterse and Peled (2014) examined the use of Twitter as a tool for supporting and achieving the goals of online internship workshops and found that a social interface creates an atmosphere of sharing. The participants were asked to send two short twits every day using a designated hashtag. Analysis of the twits and a feedback questionnaire revealed a process of creating a group that supports its members on a professional and social level. Thus, the assumption that daily writing of short messages in a workshop with only a few face-to-ace meetings strengthens participants' professional resilience was reaffirmed.

Nevertheless, the online environment also has disadvantages. Emotional difficulties expressed in the absence of immediate face-to-face communication may cause inconvenience (Gilat, 2013). Questions arising at the beginning of and during the process pertain to the extent of exposure and whether an understanding will be achieved. Motivational difficulties refer to self-discipline and self-management. Interns need to manage their learning consistently and independently. This may result in a sense of burden, whereas postponing writing may harm their and their friends' chances of success. Hence, the workshop may be unsuitable for individualized learners who may feel frustrated by the demands for sharing (Freedman & Pritzker, 2018). An online workshop requires technological literacy (Mioduser, Nachmias, & Forkosh-Baruch, 2008) which may be burdensome for new teachers.

Cognitively, participants who are less accustomed to written communication my experience difficulties and communication blocks.

Despite the differences between the environments, there is still no broad basis of knowledge about the question of the effectiveness of one type of workshop over the other. In a comparative study between face-to-face and online workshops (Rotenberg-Tadmor, 2014), no difference was found in their effectiveness with regard to achieving expected outcomes (sense of interns’ self-efficacy, using helping strategies to solve behaviour problems, educational-democratic attitudes). Hammer-Budnaro (2018) also examined the differences between the two and found that in the online workshop, evaluation of the pedagogical contribution was more prominent, whereas in the face-to-face workshop, the emotional contribution was greater.

Therefore, the online environment does not replace the traditional one, but rather extends and complements its possibilities. Research shows that satisfaction with learning in mixed environments is ranked higher than learning in programs that are fully online (Cole, Shelley, & Swartz, 2014), and that learners experience a greater sense of community than in traditional programs (Chen & Chiou, 2014). Indeed, most teaching internship programs combine the two environments at varying doses.

The following section presents a combined internship workshop which was developed owing to awareness of the advantages of each environment.

Research Method

The article is based on literature review, key theories and previous research.

Conclusion

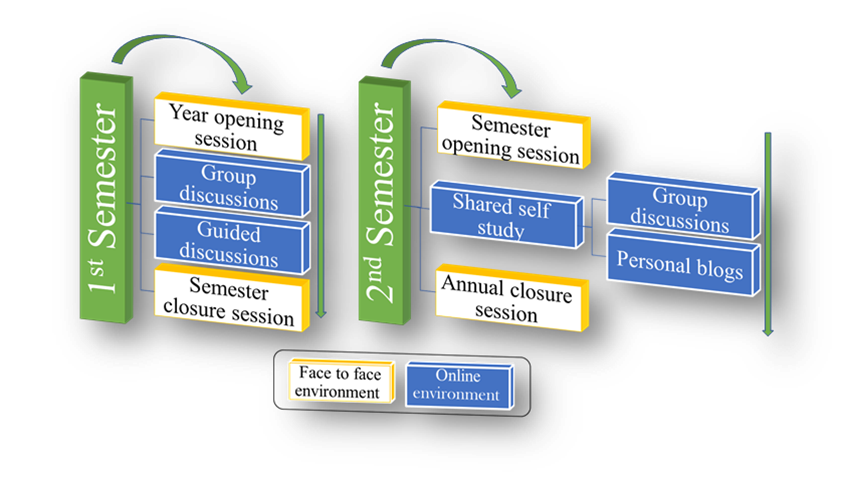

In the course of the work as a workshop facilitator and with awareness of the advantages and limitations of diverse learning environments, a model of an online internship workshop that includes components of a face-to-face environment was developed. Figure

Figure

The purpose of face-to-face sessions is meeting participants, emphasizing work procedures, sharing and feedback. During sessions, which are models of class lessons, the following are presented: optimal means of communication between teachers and students, coping with discipline and creative tools for active lessons. Participants testify to the importance of these sessions both socially-emotionally and cognitively-pedagogically: “I was anxious when I started the workshop. I must point out that the sessions calmed me. I could put faces to names. It appears that at the end of the day, we are still people who need to look others in the eyes”. It is noticeable that the very fact that face-to-face sessions exist, allows participants to sense their development as individuals and as a group, to be convinced by the presence of the instructor and to toe the line with online assignments.

Group discussions refers to activity in an online environment is mostly conducted in a group of up to five participants from the same subject area in the professional field. Interns choose content, theoretical anchors, summarize their colleagues' attitudes and report about future applications. Hence shared self-study takes place (Pritzker, 2018), whereby it is up to the group to show responsibility for contents and participation. The principle of choice in contents allows discussion of any issue, without which, it is possible it would remain their own and prevent availability to invest in educational tasks “A small corner, on a group computer blog, allowed me to complain about things I would never dare to say aloud to anyone at school, to show a lack of confidence, and then to come out stronger, more knowing and confident to my work”.

Content choice considered together serves as an impetus to optimal learning: “I think shared learning is so important… the main thing is mutual reinforcement and tips given on the basis of personal and professional life experience”. The group is a space for close social ties that contribute to a sense of togetherness and emotional confidence, by which it is easier to traverse the year’s complexities: “My group colleagues were my tail wind, and even when I felt that I wasn’t necessarily advancing along the right route, they expressed their opinions ethically, respectfully and collegiately and also knew how to direct me to other areas”. Empathic and accepting discourse, as well as being non-judgmental in reactions are mentioned as key factors in the workshops contribution: “Honest sharing with the group, without considering what they will think of me and what they will say about me, contributed to me personally and I learned that it was worthwhile to unload and share, because we are all in the same boat and are coping with the same difficulties…”.

During the first semester, there are guided discussions, initiated by the facilitator and obligatory for all participants. Their contents are taken from the induction stage, such as: acclimatization and absorption into the education system, assessment and feedback as well as one of the most frequent topics, for example: coping with children with challenging behaviours or communication with people who share the same role. Most discussions included questions to address, guidelines for reading diverse theoretical and practical sources, describing experience, consolidating insights and finding new ways of coping. Hence it is guaranteed, in spite of the constructivist view on which the workshop is structured, these core issues are addressed. It should be noted that participants respect the discourse in discussions: “There are your (facilitator’s) reactions that escape the confines of the screen and accompany me. Reactions making me reconsider a question”.

In addition, online discussions are likely to benefit participants because they are models of conducting online debates, which they could apply in their teaching. This benefit is important in light of the demand on teachers to exploit the online environment for shared and meaningful study.

In the second part of the workshop, each intern chooses a topic for in-depth examination which they research personally, with the help of their group. Similar to action research (Reason & Bradbury, 2001), they have to explain the rationale for their choice, phrase a research question, build an action plan and document their progress. Research stages are discussed on the group blog and at the same time, on a personal blog where each intern engages in a dialogue with the facilitator.

The benefit of an online environment in research derives mainly from the advantages of written documentation of the process. Hence it is possible to make use of information accumulated. Detailing their factual and experiential experiences contributes to rich and beneficial learning: “I was pleased to scroll back to the start of the blog and see there were issues in which I had already succeeded and I feel less ‘new’”.

A cognitive advantage of writing is expressed by it helping organized and creative thought: “With the help of writing, understandings I already had, but had never said in words were clarified. In fact, until I put my thoughts on paper, I had never considered them important. In hindsight, in writing, I slowly found that I expose my beliefs, my preferences, the red lines I am not prepared to cross, and thus without paying attention, reflected to myself, like a mirror, the route I choose”.

Choosing an authentic issue present in an intern’s daily professional life, constitutes a source of change and learning outside workshop boundaries. Interns testified to an expansion of inter-professional links at school by considering, planning and executing the content they had chosen. Even if the research did not accomplish its goal, did not diminish the learning experience. The sense of ability to ignite processes and formulate initiatives increases: “Over and above helping me resolve a particular situation, research processes led me to recognize that sometimes one has to stop to see the way ahead. I am of the opinion that my greatest insight was that over and above actions and operational steps, the intention and even how words are verbalized acquires meaning”.

Alongside the advantages of the model detailed above, it is important to present its main limitation expressed in the gap between learners' expectations and reality. Many of the learners believe that learning in an online environment requires fewer efforts. Perhaps they project the practical convenience of learning (at the learner's place and pace) to the efforts involved in the actual learning. In practice, investment in online learning is greater, and thus learners may be disappointed.

This article examined the rationale for a teaching internship workshop. It discussed the changes that have occurred in the different learning environments and their implications on the workshop. The main conclusion arising, is the notion of combining the two learning environments in response to developmental, personal and professional needs of teachers in the first stage of their educational journey.

The literature review and accumulated experience reveal that personal adjustment is essential to online learning, and hence the optimal model ought to consist of both learning environments, exploit the advantages of each and increase the workshop's contribution to teaching interns.

Currently, the Ministry of Education formal position towards the combined internship workshop is reserved. The Ministry allows every educational institution a rate of 20% online internship workshops to be online. This position may reflect fear of shallowness of interpersonal processes that take place in online communication. It is likely that these concerns rely on intuitive perceptions rather than empiric information with regard to processes that actually take place. It is important to examine the proposed model empirically and hear the voices of partners in the process – interns and facilitators – with regard to the learning experience and its contribution the interns' professional development as teachers.

References

- Aflalo, E. (2012). Contradictions in teachers' perceptions: The invisible barrier to integrating computer technology in education. Dapim, 54, 139-166. (In Hebrew).

- Bandara, D., & Wijekularathna, D. K. (2017), Comparison of student performance under two teaching methods: Face to face and online. International Journal of Education Research, 12(1), 69-79.

- Barak, A., & Boniel -Nissim, M. (2011). The internet for the help of adolescents: Therapeutic value of blog writing. Mifgash, 34, 9-30. (In Hebrew).

- Boniel-Nissim, M. (2010). The therapeutic value of adolescents’ blogging about social–emotional difficulties (Doctoral Dissertation). Israel: University of Haifa. (In Hebrew).

- Carpenter, J. P., Cook, M. P., Morrison, S. A., & Sams, B. L. (2017). “Why haven’t I tried twitter until now?”: Using twitter in teacher education. Learning Landscapes, 11(1), 51-64.

- Cassidy, J., & Shaver, P. R. (2016). Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Chen, B. H., & Chiou, H. (2014). Learning style, sense of community and learning effectiveness in hybrid learning environment. Interactive Learning Environments, 22(4), 485-496.

- Cole, M. T., Shelley, D. J., & Swartz, L. B. (2014). Online instruction, E-Learning and student satisfaction: A three-year study. International Review of Research in Open & Distance Learning, 15(6), 111-131.

- Dickman, N. (2005). Writing as a vehicle for reflecting and enhancing learning process of mathematics teachers in the course of becoming mathematics teachers educators (Doctoral Dissertation). Israel: Technion, Haifa. (In Hebrew)

- Director General's Circular (2014). Implementation circular towards the 2005 school year – Teaching internship. Jerusalem: Ministry of Education. (In Hebrew)

- Drange, T., & Roarson, F. (2015). Reflecting on e-learning: A different challenge. E-Learning & Software for Education, 2, 442-446.

- Fisherman, S. (2011). The novice's organizational literacy: school in the novice teachers' perception and as presented to them by the principal. In A. Shatz-Oppenheimer, D. Maskit, & S. Zilbershtrom (Eds.), To be a teacher: On the path to teaching (pp. 151-180). Israel: Mofet. (In Hebrew)

- Forkosh-Baruch, A., Mioduser, D., & Nachmias, R. (2012). ICT innovation in the international research. Journal of Theory and Research Ma'of u Ma'ase: Teaching and Learning in the Internet Era, 14, 49- 22. (in Hebrew)

- Freedman, V., & Pritzker, D., (2018). On the Journey from ‘There Is Someone to Talk to’ to ‘There is Someone to Learn with’ – Collaborative Learning Experience in an Online Group. In D. Pritzker (Ed.), To Experience and Feel – Collaborative Independent Learning in Academia (pp. 139-160). Tel Aviv: Mofet. (In Hebrew)

- Gilat, I. (2013). Only on the internet can I share what I am going through. Mental help in an online environment. Tel Aviv: Mofet. (In Hebrew)

- Hammer-Budnaro, D. (2018). Online workshop versus "face-to-face" workshop during the induction phase. Dapim, 67, 161-183. (In Hebrew)

- Harper, B. (2018). Technology and teacher-student interactions: A review of empirical research. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 50(3), 214-225.

- Hershkowitz, A., & Kaberman, T. (2009). Training and professional development of teachers via distance learning as a way of coping with the shortage of teachers: Initiative for applied research in education. Haifa: Israel Institute of Technology Department of Education in Technology and Science.

- Hussein-Farraj, R., Barak, M., & Dori, Y. J. (2012). Lifelong learning at the Technion: Graduate Students’ Perceptions of and Experiences in Distance Learning. Interdisciplinary Journal of E-Learning and Learning Objects, 8(1), 116-135.

- Ingersoll, R. M., & Strong, M. (2011). The Impact of Induction and Mentoring workshops for Beginning Teachers: A Critical Review of the Research. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 201–233.

- Kupferberg, I. (2013). Constructing online interpersonal communication through discourse resources. In I. Gilat (Ed.), Only on the internet can I share what I am going through. Mental help in an online environment (pp. 100-114). Tel Aviv: Mofet. (In Hebrew)

- Lazovsky, R., & Zeiger, T. (2004). Teaching internship: evaluating interns in different training tracks. The contribution of the mentor, the internship, and the program as a whole. Dapim, 37, 65-95. (In Hebrew)

- Libman, Z. (2013). Learning, understanding, knowing: Exploring pathways to constructivist teaching. Tel Aviv: Mofet. (In Hebrew)

- Lotan, T., & Shimoni, S. (2005). The development of professional thinking of teachers in the first year of their work during an online discourse of difficulties. In A. Kupferberg & E. Olshtain (Eds.), Discourse in education: researching educational events (pp.75-111). Tel Aviv: Mofet. (In Hebrew)

- Luo, T., & Franklin, T. (2012). “You got to be follow-worthy or I will unfollow you!” Students’ voices on twitter integration into classroom settings. In P. Resta (Ed.), Proceedings of SITE 2012—Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 3685-3688). Austin, Texas, USA: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

- Luo, T., Smith, J., & Cheng, L. (2016). Preservice teachers’ participation and perceptions of Twitter live chats as personal learning networks. Tech Trends, 61(3), 226-235.

- Maskit, D., & Yaffe, A. (2007). Voices from novice teachers’ inner homes: Interns write about themselves and about teaching. Iyun umehkar behachsharat morim, 11, 40-70. (In Hebrew)

- Maskit, D., & Dickman, N. (2006). From “student-teacher” to “becoming a teacher”-Story of a beginning. In A. Kupferberg & O. Olshtain (Eds.), Discourse in education: researching educational events (pp. 21-48). Tel Aviv: Mofet. (In Hebrew)

- Mioduser D., Nachmias R., & Forkosh-Baruch A. (2008). New Literacies for the Knowledge Society. In J. Voogt & G. Knezek (Eds.), International Handbook of Information Technology in Primary and Secondary Education (pp. 23–42). New York, NY: Springer.

- Nasser-Abu Alhija, P., Fresko, B., & Richenberg, R. (2011). The process of teaching specialization: Overview. In A. Shatz-Oppenheimer, D. Maskit & S. Zilbershtrom (Eds.), To be a teacher: On the Path to Teaching (pp. 55-87). Israel: Mofet. (In Hebrew)

- Peechapol, C., Na-Songkhla, J., Sujiva, S., & Luangsodsai, A. (2018). An exploration of factors influencing self-efficacy in online learning: A systematic review. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 13(9), 64-86.

- Peled, Y., & Pieterse, E. (2013). “Is there anybody out there”: Twitter as a support environment for first year teachers’ online induction workshop. Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference, 2013(1),1405-1410.

- Pieterse, E., & Peled, Y. (2014). A chaperone: Using Twitter for professional guidance, social support and personal empowerment of novice teachers in online workshops. Interdisciplinary Journal of E-Learning and Learning Objects, 10, 177-194. https://doi. org/10.28945/2068

- Pritzker, D. (2018). To experience and feel: shared independent learning in Academia. Tel Aviv: Mofet.

- Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (2001) Handbook of Action Research. London: Sage.

- Rotenberg-Tadmor, Y. (2014). Enhancing Outcomes in Teacher Internship workshops: Comparing Face-to-Face with Online Groups (Doctoral Dissertation). Haifa: University of Haifa. (In Hebrew)

- Sela, A. (2010). The great fun I have with you: an asynchronous forum as means of communication in an internship workshop. In Mechkar, Iyun Veyechira Beoranim. Oranim, Israel.

- Shonfeld, M., Hoter, E., Ganayem, A., & Walter, J. (2015). Online teams, trust and prejudice. Issues in Israeli society, 19, 7-40.

- Stapleton, J., Tschida, C., & Cuthrell, K. (2017). Partnering principal and teacher candidates: Exploring a virtual coaching model in teacher education. Technology and Teacher Education, 25(4), 495-519.

- Wasserman, E., & Migdal, R. (2019). Professional development: Teachers’ attitudes in online and traditional training courses. Online Learning Journal, 23(1), 132-143.

- Yaniv, H. (2017). What does the digital world do to our children and to us? In R. Wadamany (Ed.), Digital pedagogy: From theory to practice. Tel Aviv: Mofet. (In Hebrew)

- Zach, S., Talmor, R., & Stein, H. (2016). Internship in teaching: The perspective of interns in physical education. Batnua, 2, 228-253. (In Hebrew)

- Zilbershtrom, S. (2013a). Policies of the Department for Internship and Teacher Induction. In S. Shimoni & O. Avidav-Unger (Eds.), On the continuum: Training, induction, and teachers’ professional development – Policy, teory, and practice (pp. 95–100). Tel-Aviv, Israel: Ministry of Education and the Mofet Institute. (In Hebrew)

- Zilbershtrom, S. (2013b). The induction stage into the teaching profession. In S. Shimoni & O. Avidav Unger (Eds.), On the continuum: Training, induction, and teachers’ professional development – Policy, theory, and practice (pp. 101–131). Tel-Aviv, Israel: Ministry of Education and the Mofet Institute. (In Hebrew)

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

17 June 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-084-6

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

85

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-814

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Freedman, V., & Cucos, C. (2020). Model Combining Learning Environments In Teaching Internship Workshops. In V. Chis (Ed.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2019, vol 85. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 57-67). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.06.6