Abstract

The following paper tries to establish the main motivations for which adults choose to study foreign languages in non-formal education - through classes offered by private companies. It focuses on establishing the main age groups, education level, social status and interest in languages to see how that reflects upon the position of non-formal, linguistic, adult education in contemporary Romanian urban society and its role in the integration of immigrants. Adult education usually focused on more of a professional or technological training and language classes have not been a common choice until after Romania opened to a global capitalist market. Thus, the pedagogy of foreign languages for adults is a new field of study, that has not yet been explored thoroughly. The study is based on 100 adults, Romanians who chose to learn foreign languages and foreigners who are learning Romanian, in the city of Cluj-Napoca between 2018 and 2019. The study used questionnaires given to the subjects at the beginning of their classes, focusing on their identity and individual motivation. The results show that there are some clear trends in the category of people who enrol themselves for such classes, from an educational, professional and age wise perspective.

Keywords: Adult educationlanguage,non-formalimmigration

Introduction

Non-formal education exists in Romania in the form of evening classes aimed at the public who hadn’t gotten certain degrees at the right time and were looking to improve their situation. However, after joining the European Union and getting into a globalized market, demands for other types of classes appeared, especially of foreign languages. Companies with foreign capital are now present in larger cities in Romania and they serve as an international market, making communication very important for staying competitive and increasing their profits. They need skilled workers who not only are professionals in their fields but also speak at least two or three languages. Often the level of fluency required is not that of a proficient or academic speaker but enough to communicate politely and efficiently in a business environment. Thus, non-formal education has developed to cater to these needs, mostly in medium to large cities because they have the highest percentage of foreign investments. Also, seeing as Romania has the second fastest internet in the world makes online business and education much better than in other regions.

Due to opening to the global market and the European trading space, Romania has seen not only emigration but, in recent years, immigration. Immigration can be of two types: permanent and transitory. There are some people who come and settle in the country permanently and wish to be as integrated as possible and some who come to stay for a few years for their job or business and need to get along on a daily basis with the Romanian community. They have created a new requirement in non-formal education, for Romanian classes catered to foreigners and a new pedagogy of this language as foreign. This immigration is seen again mostly in larger cities, because there are more companies there and offer more temporary jobs for non-natives. The integration of adult immigrants, whether they are here to stay or just to visit for a while is realized linguistically through non-formal educational facilities, with the exception of university classes designed specifically for their incoming students, which are not open to a larger public. The first choice for most adults in learning Romanian is by attending a private class at a private company.

In Romania, formal education has been for a long time almost the only way of studying a new field and for languages private tutoring was also a choice. However, only after the fall of Communism did we see the emergence of private companies that deliver classes in various fields, making it a new and understudied phenomenon with special requirements that are often unmet. Traditional pedagogy is aimed entirely at children and often approaches adults in a similar way, which is not efficient. Especially when it comes to teaching languages, most workbook are designed for children and only in recent years books for adults have appeared on the market. The pedagogy of adult language teaching is at the beginning, especially for Romanian and there is a need for analysing their specific requirements and delivering better quality classes and working materials.

The paper will assess 100 individuals who chose language classes, through questionnaires about their identity and motivations in order to find the main trends they fit in. They are both Romanians and foreigners, men and women who have contacted private companies for language lessons. The questionnaire aims to establish their educational level, professional background, age, current occupation and individual motivations and see what they reflect about non-formal adult education in a medium sized city in Romania. The second and the third part of the article will establish the theoretical background and main research questions and the finding will be explained in detail in the fifth part of the article, followed by some conclusions.

Problem Statement

Communication and learning

If personality represents the internal representation of the psyche, then behaviours and verbal expressions are phenomena that show the desires, motivations and the declared or hidden needs. In motivational theories, motivations are realities inscribed somewhere in the psyche and the logical system guiding behaviours and expressions is only postulated. "Desires, motivations, values are actually grids of a world perception and determined profound attitudes, that is supositions about things" ( Mucchielli, 2015, p. 12).

The suppositions will determine someone’s acts, originating in their attitudes, then their opinions as verbalizations of their position in regard to something. As the above mentioned author sais in the quoted book: a small number of desires and values are the basis of a great number of attitudes, then an even greater number of opinions because they express evaluations of a great number of things from daily life. By studying opinions, we will also find the atitudines and values behind them ( Mucchielli, 2015).

Through communication, personal values and beliefs are automatically suggested in connected to the sent message, so very rarely is something communicated in a completely objective way. Values are called self-attributed motivations of which the person isn’t really aware.

Self-disclosure is not necessarily done consciously but often without the direct wish of the person, through the attitudes they cannot control or through non-verbal language. In some cases, the other people around see better what desires, needs and frustrations someone has because they can see from the outside the manifestation of the true self, while the person itself can feel that the mask they use is working. Implicit motivations cause spontaneous behaviours, self-attributed motivations create immediate specific answers or carefully chosen behaviours to particular situations. Individuals from different cultural groups are preoccupied to do something well but that something is defined by the motivations and purposes that they attribute to themselves, in part determined by what is considered important in the group they belong to.

In our communication we show ourselves, the social group that we belong to, our culture and the historical moment that we are living. Even if we are conscious about these things, they cannot be hidden from others and cannot be changed without the changing of the surrounding reality first, by gaining a new social status or through defining existential events like graduation, marriage, death, etc.

Paul Freire represents an important voice in adult education through his democratic visions and the literation methods he developed and successfully used in under-privileged areas in South America. He managed to synthetize in a philosophical way the essence of human communication and its highest purpose – to transcend personal limits by connecting to a universal existence. He also raised some controversies, in part due to his idealism and belief in the human capacity to develop oneself in harmony with others and the environment.

He presents a philosophical view on education and offers it to common people, regardless of their level, as an instrument for knowledge of the world and themselves. The success he had is not without risk, as his message is always open to personal interpretation and ca be used for manipulation. But it proves to be better fitted for today’s society, so individualistic and dynamic, where independent learning becomes more and more important. However, both in communication and in learning, the individual ca be its own enemy.

Interest is connected to affection, we have an interest in something if we like it, if it stimulates us or if it can help us get to our desired position – in this case, even though interest is based on external factors, it depends on an internal desire or need ( Martins, 1993).

No interest is completely void of emotion, whether it’s due to a personal or professional need and must be seen in relation to the individual personality. This doesn’t mean that motivation will forever be transparent as it is often vaguely known by the persons themselves or badly understood and attributed to external elements.

One must, however, make a distinction between interest based on pleasure, in which a certain activity or study gives pleasure and an interest based on the results of an activity or study. In the case of adult education, the main interest are the results of the instruction and rarely the activity of studying per se or simply interest in the field. Performance does not depend on the type of interest but on the complete lack of it. Initial interest or other knowledge of a certain filed determine the reactions towards new information. If there is already a preoccupation for the object of study, it will be considered interesting and more attractive and learning will be done almost automatically.

Multiculturality and globalization

Teaching foreign languages in an inter-cultural context means teaching about a culture, its customs, a tradition to people who also come with their own social and cultural identity. The knowledge they have of one another depends on the people themselves but also on their country of origin and the shared history of certain nations. Another aspect, of a political nature is the dominant culture in a historical moment in a particular space. If we consider the United States, for example, the people’s knowledge about this country will depend on the relations between their country of origin and the shared history. Some subjects or cultural aspects cane be sensitive, that’s why the teachers needs to be open to other cultures and overcome their own stereotypes to be able to remain as objective as possible towards their students, who are of all ages and come from all walks of life ( Byram, 1997).

The cultural awareness of each person interacting with another from a different culture can be of several kinds: historical, social, religious and often cantered around the national identity built by education. It comes from stories, personal experience, previous interactions and the international image, whether fictitious or realistic, that each nation has. Their impressions will be compared between themselves or to the present reality, creating either stronger convictions or a dissonant perception.

The problem of the English language is often debated because of this, as it is seen to represent western culture and values and can be rejected as such – in Saudi Arabia or other Arab states although rarely in Romania. A similar phenomenon happens here with Russian as a representant of the history and culture of the country and the recent relations between the two can turn cultural dialogue into a sensitive act.

The teaching of English or the teaching of a foreign language to Romanians raises linguistic problems. Firstly, it is often not taught by a native speaker and the accuracy of the information provided can vary. The language can also be taught with mistakes or outdated vocabulary.

Language is a living object, rapidly changing and non-natives who teach cannot keep up with what happens in another part of the world. However, one must ask how much such a thing is relevant to the teaching of international languages like English and French and how much their status as such opens them up to regional influence and change ( Prabhu, 1994) as once happened to spoken Latin. The benefits of knowing an international language overrun the deficiencies that appear from possible mistakes. The responsible usage of the language and awareness of the existing limitations can alleviate the passing of erroneous information. Given comparable learning conditions it is equally reasonable to look at the quality of the samples given as being more important than their quantity. Namely, that learning basic structures that can afterwards be developed and applied is more useful than a vocabulary of high complexity, taught by a native. Learning a foreign language through a non-native is more useful than not knowing it at all.

Other studies on adult language learning

The study of adult language learning is still at the beginning. There have been some more studies done on the English language in the United States or some European languages in Europe, but there are no studies of this kind done on Romanian. In

Then, in

A study on Italian - The motivation of adult foreign language learners on an Italian beginners’ course: An exploratory, longitudinal study - was done by Ferrari ( 2013). It focused on English speakers learning Italian during a beginner’s course. It is a qualitative, longitudinal investigation using semi-structured interviews undertaken at the beginning, middle and end of a 30-week Italian beginners’ course, using the. Process Model of L2 motivation. ( Ferrari, 2013) The findings focus on establishing the factors responsible for sustaining interest and participation in the course, even though they might not reflect the initial motivation and considers social participation and leisure participation motives. The thesis’ ambition is to propose a new conceptual model that represents second language learning motivation in general.

Research Questions

This study was designed to find out who chooses to study foreign languages in non-formal education and what are their motivations in order to identify some major trends about their social status, origin and requirements. It considers both natives and immigrants. The two categories are found together in this study because they are both formed of adults who choose to study foreign languages in a private non-formal education environment and the pedagogical requirements for the two are the same. The demand for Romanian as a foreign language has increased, making it one of the most in demand languages on the private market in the city of Cluj-Napoca after English and German.

The Romanian natives

Language classes are more and more requested by native Romanians who wish to learn a new language or improve one they’ve studied before. The major demands are for English – although it’s the most studied language in schools, German – in the region of Transylvania and Bucharest, French, Spanish, Italian – every so often. Although some of these languages are studied in schools it appears that students don’t graduate with a level that is advanced enough to serve their professional needs and seek private lessons as adults. The research wishes to see what are the main social groups that these people belong to, from an educational and professional perspective in order to better understand their needs, the faults in their formal education and develop more efficient study materials.

The Immigrants

The demand for Romanian classes has increased in recent years as Romania is seeing some forms of immigration. As it was mentioned before, this can be permanent or transitory but regardless of the condition of these people, language classes should be delivered in the same way. However, the pedagogy of Romanian as a foreign language is a very new development and hasn’t really been explored, resulting in workbooks that are inappropriate for adults, inefficient and incomplete. By analysing who are the foreigners who request private Romanian language classes and why, the pedagogy of the language can be developed to match the necessities of the market with better materials.

Purpose of the Study

As stated before, the purpose of this study is to discover the major social and economic categories of people who choose language classes in non-formal education and their main motivations and try to find the connections between them and the present job market in a globalized world. It also aims to identify the present trends in immigration in a large city in Romania and to some extent even of emigration of educated Romanians.

Research Methods

The research method is a small N survey, with questionnaires that I have developed myself as the instruments. The questionnaires are designed to discover the main motivations of the people who study languages, by identifying certain things about the social status of the people involved, like age, gender, ethnicity, education level, profession and then more personal motivations. The motivations range from professional obligations to social needs to personal interest to emigration. This study is exploratory and not confirmatory.

The choice of respondents was mostly influenced by feasibility issues as the study was done through a collaboration with a private language company in Cluj-Napoca, but they consist of both men and women, Romanians and foreigners, of all ages. They were given the questionnaire during their classes, so it had to be easy to fill in and not take too much of their time. I have chosen questionnaires instead of interviews because they allow a generalization of major trends and offer closed answer questions, with the benefits that the results are standardized easier and get a synthetic analysis. Interviews would have been difficult to do in a private setting as the respondents don’t want to waste too much of their time doing something unrelated to the studies that they are paying for, so very few would have agreed to more that filling out a questionnaire. This is more of a pilot study of a new area in education in Romania and the rather small sampling is supposed to identify the major trends that can be further explored in the future. The questionnaire has two main parts, the first one made up of eight choices, designed to assess the subjects social background, educational level, profession, age and gender and the second one, made up of five closed questions aiming to establish the more personal factors of motivation. The questions are why they chose a private language course, what they wish to gain from it, what opportunities they expect by learning said language, how involved in the learning they think they will be and how many hours of study are they willing to allocate per week. Each question is followed by a list of statements to which the subject can agree, partially agree or disagree. The questionnaire itself can be found at the end as an appendix.

Findings

The questionnaires were given to 100 people aged 20 to 55, who all attended private language classes, 57 men and 43 women, 60 Romanians and 40 non-Romanians of many nationalities. Of them 52 were between the ages 20 to 30, 43 were between the ages 31 to 45, 5 were between the ages 46 to 55.

Of all the subjects 85 had a university degree, 14 had a high school degree, 1 had a PhD; 50 worked in a technical field, 15 in an economical field, 15 in a corporate field, 10 in design, 3 in a medical field, 2 in Law, 5 in an executive field. 80 of them were currently employed, 10 owned their own business, 2 were homemakers, 3 were unemployed, 4 were students and 1 was retired. 73 had some knowledge of English, 36 of German and 15 of French.

Already from the more general questions, some clear trends appear, no matter what the ethnicity of the subjects. The biggest age group choosing to study foreign languages privately are between the ages 20 to 30, followed closely by the 31 to 45 age group. Few people above 45 seem interested in linguistic non-formal education. This can be linked to the necessity of the studies, which will be described further down. Most people have a university degree and are currently employed, either in a technical, economic, corporate or creative field. Most of them already had some prior knowledge of an international language as seen in Figure

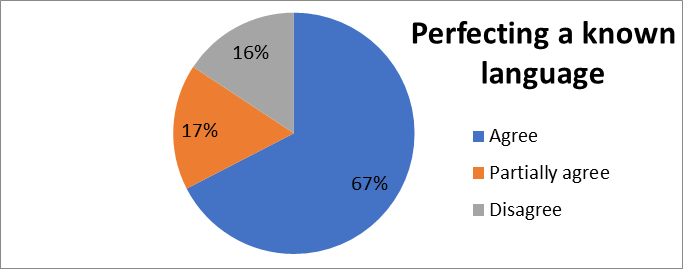

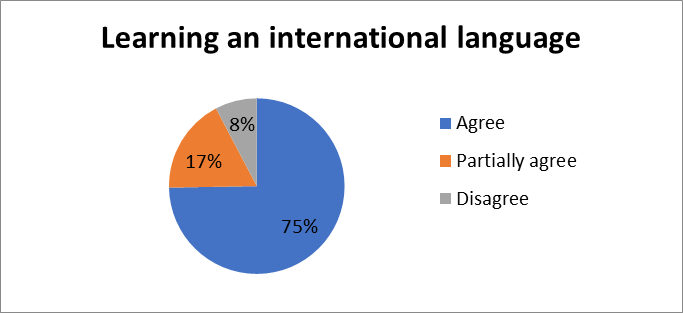

60 of them want to perfect an already known language, 68 want to learn an international language as seen in Figure

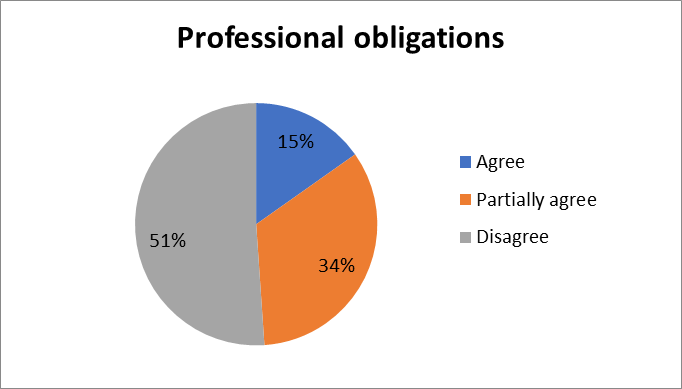

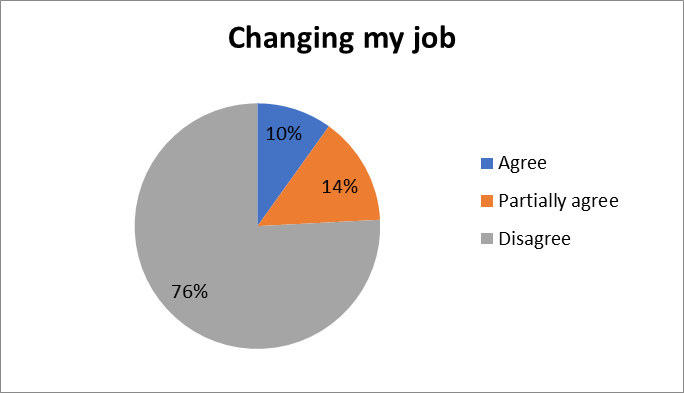

As it can be seen from the more personal questions, the main motivations of studying a foreign language seems to be related to the professional field, whether it is required for the job itself or it is a plus in the long term, followed by a desire to fit into the community, as seen in Figure

These are the main trends that can be found both with Romanians and foreigners studying language classes in Cluj-Napoca in the year 2018-2019. Further I have divided the two in order to see what is different between the groups.

Romanians

The assessment showed that the Romanians who chose to study foreign languages in non-formal education were almost equally split between men and women, with no overpassing the other. The main languages demanded were English and German, followed distantly by French and Spanish. The German need can be explained by the presence of many German companies in Transylvania and Cluj-Napoca, where the study is based. As for English, even though it is studied in schools for as much as twelve years, it appears that the level achieved by the students is not advanced enough for the demands of a global job market. This points to deficits in the formal education received at school, which, despite its lengthy duration, does not offer enough to cover for the real necessities of the job market, leaving graduates without proper training. The main age categories are 20 to 30 years, followed by 31 to 45 years, with few students over 45 years old. About 80 % have a university degree and were employed at the moment of the study. They work in technical fields, followed by corporate and economic.

As for motivation, the main trends are the study of an international language, perfecting an already studied language, professional obligations or changing the current job and personal interest in the language. As the first motivation is professional, it appears that people without a university degree work in fields that either don’t require much knowledge of foreign languages or that they are not interested in advancing their position, which would need them to continue their studies. Emigration was rejected as a motivation by 80%. However, those who emigrate could learn the language of their new country when they arrive there and not before or they could already have some knowledge of it prior to their departure, making them able to get by.

Immigrants

The non-Romanians who chose to study Romanian in a non-formal private setting came from many different national backgrounds, with no country being represented predominantly. However, the gender division is different to that of the natives, with a 65 % to 35 % ration of men to women, namely, a greater part of transitory of permanent immigrants were male. Most of them are between the ages 20-30 followed by 31-45 and have a university degree. Their main motivations are better social integration and language fluency, an interest for the language and personal/ family obligations. It doesn’t seem that knowing Romanian is very needed in the workplace as these people mostly work in international companies and speak English with their colleagues. This connects to the fact that Romanians of the same field tend to learn foreign languages in order to use them at work. However, depending on their work environment, they might need to use it in communicating with older colleagues, who are less fluent in English. Again, 80 % are employed and the rest have their own business. If they are interested in settling here, then Romanian is the language they use to communicate to their Romanian partners and their families and relatives. The decision to learn the language of their new country shows that they are interested in local culture, at least superficially and would like to be somewhat integrated. The presence of more men than women is interesting, and it can point to several things. First, due to the smaller sample of participants in the study, it could be that by chance more men were chosen to take part, however, it can also point to the fact that immigration to a new part of the world, in this case, Eastern Europe, can be viewed as a more dangerous and pioneering thing and women prefer to stay in a familiar community, perceived as a safer choice.

Conclusion

Through this study I set up to discover the main trends in adults who choose language classes in a non-formal setting in a medium city in Romania, taking Cluj-Napoca as an example. Cluj-Napoca is representative for an Eastern European middle to large city, that is in a stage of expansion and development and is opening to a global market. Cities of the same region and size can have a similar market and a study made here can be considered a sample for what is happening in other places.

The major trends in adult education focused on language learning reveal that the majority of people who choose private classes, regardless of their ethnicity, belong to the age category of 20 to 30 years old, followed by a 31 to 45 years old category, have a university degree, are already employed, tend to be more men than women, as they work in technical, economical and corporate fields, and are mostly motivated by professional needs and workplace demands. They are willing to pay for private lessons but hope to learn the new language mostly by attending the class and not so much through individual effort at home, because their main interest in continuous education is professional in nature. The foreigners who come to Romania for a period of time or to settle here see learning Romanian as a way to be better integrated in the local community but also as a tool for better communication with their colleagues at work.

The limitations of this study are due to the relatively small sample of subjects analysed so far, that reflect the bigger trends and the fact that the questionnaires used have set answers, whereas interviews would have yielded more detailed results. The study could benefit in the future by expanding the number of subjects in order to see how trends evolve and change. The same type of study could also be done in other cities in Romania and Eastern Europe in order to see how the situation there compares to that in Cluj-Napoca, in terms of similarities and possible differences.

Appendix

Questionnaire

Sex: M/ F

Nationality:

Mother tongue:

Studied language:

Other spoken languages:

Age:

20 – 30 years

31 – 45 years

46 – 55 years

Over 55 years

Last school graduated

Middle school

High school

Bachelor’s Degree / Master’s Degree

PHD

Current profession ...............

Status:

Employed

Owner

Home maker

Unemployed

Student

Retired

-

Mark with X in the following template according to your agreement to each statement. I choose to attend a language course for:

-

Mark with X in the following template according to your agreement to each statement. Through this class I wish:

-

What opportunities do you think learning the language will bring?

-

How do you think you will get involved in learning the language? Mark with X your choice in the following template:

-

I will allocate so many hours a week for studying:

-

Up to an hour

-

1 – 3 hours

-

3 -5 hours

-

Over 5 hours

-

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the company Linguastar, based in Cluj-Napoca that I collaborated with for allowing me to do this study and facilitating my work.

References

- Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural Communicative Competence. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Ferrari, L. (2013). The motivation of adult foreign language learners on an Italian beginners’ course: An exploratory, longitudinal study. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5736/68b097613-abc93af449df7014b204759ac9c.pdf

- Martins, D. (1993). Les facteurs affectifs dans la comprehension et la memorisation des textes. Paris, FR: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Mucchielli, A. (2015). Arta de a comunica. Metode, forme și psihologia situațiilor de comunicare. Iași, RO: Polirom.

- Oxford, R., & Ehrman, M. (1995). Adults' language learning strategies in an intensive foreign language program in the United States. System, 23(3). Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0346251X9500023D

- Prabhu, N.S. (1994). Second language pedagogy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Weger, H. (2013). RELC Journal on March 11. Examining English Language Learning Motivation of Adult International Learners Studying Abroad in the US. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0033688212473272

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

17 June 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-084-6

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

85

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-814

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Onutz, T. (2020). Foreign Languages In Non-Formal Adult Education - A New Trend. In V. Chis (Ed.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2019, vol 85. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 507-519). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.06.51