Abstract

This study is aimed at studying the specifics of perceptions of “good life” in teenagers at risk of forming deviant behaviour. The pilot study involved 40 teenagers aged 12-16 who systematically violate social norms and rules and are under intra-school control as a group at risk of forming various forms of deviant behaviour. The control group, performing a representative sample (sex, age, family composition, material wealth, neighbourhood of residence) included 40 teenagers with social and normative behaviour studying at the same comprehensive school. The results of this study show that meaningful ideas about “good life” in teenagers at risk of forming deviant behaviour and teenagers of the conditional norm have significant differences. There found statistically reliable differences according to following criteria “friends”, “family”, “freedom”, “entertainment”, “power”, “health”, “love”, “education”. The studies of teenager assumptions about “good life” allow defining the attributes of wellbeing of teenagers with deviant behaviour. As the main attribute of “good life” for teenagers with deviant behaviour, material prosperity (financial success) is found. The differences in assumptions of “good life” between teenagers with positive socialization and teenagers with deviant behaviour consist of basic believes about subjective welfare that is a purpose for different methods of upbringing. The results of studies can be applied in practical work with children of “risk groups” having socialization problems.

Keywords: Teenagersdeviant behaviorgroup at-risk

Introduction

The problem of forming deviating behaviour in adolescence is extremely significant for teaching practice. Without understanding the risk factors of deviation formation, it is virtually impossible to organize effective psychological and pedagogical support of a growing person in complicated conditions of social development. Adolescence is a sensitive period for testing pro-social or asocial behaviours ( Belobrykina & Limonchenko, 2017; Bayanova & Minyaev, 2018; Koshenova, 2019). In the research of Rezazadeh and Bayanova it is shown that “stable behavioural reactions of a person to norms act by way of normativity as property of his personality” ( Rezazadeh & Bayanova, 2017, p. 11), and a teenager due to age tasks, chooses a “system of coordinate” of his further development, chooses vital reference points, determining and personal concept of the norm. The results of this study revealed that teenagers inclined to deviant behaviour have a specific view of “good life”, the differentiating sign of which in their view is entertainment; Material wealth giving an opportunity to feel superiority over others; Freedom, understood as a lack of obligations. Along with the devaluation of the emotional component of life, they are characterized by a conscious rejection of cultural congruence and the choice of a criminal system of coordinate for self-realization. The revealed peculiarities of perceptions of “good life” in teenagers group at risk provide an opportunity to individualize and optimize the psycho-correction work of the school psychologist and social teacher in regard to deviant teenagers.

Problem Statement

The key questions of deviantology are the dilemma of choosing sense-life reference points, the ability to design and represent future, including the formation of a way of a good and happy life.

The term “good life” in scientific thesaurus still lacks an exact definition. An analysis of the works of Inglehart ( 1997), Ryan and Deci ( 2000), Easterlin ( 2006), Diener and Ryan ( 2009), Seligman ( 2011), and other researchers, shows that the issue of perceptions of “good life” in American psychology is mostly viewed not as independent, but only in terms of the concepts of “happiness” and “subjective well-being”. In Russian psychology, Djidaryan ( 2013), Karapetyan ( 2014) and a number of other researchers propose to distinguish between activity, demand, value and normative approaches to determine the phenomenon of subjective quality of life. Shamionov ( 2008) considers subjective well-being as a concept expressing his own attitude to his personality, life and processes, which are important to him in terms of learned normative ideas about the internal context, and characterized by a sense of satisfaction.

Nevertheless, despite the sufficient development in psychology of the category “subjective well-being”, the concept of “good life” up to present time remains content-free and often occurs in a formally generalized interpretation, without clear operationalization of its components. At the same time, the importance of social and psychological research in the field of understanding the phenomenology of good life and its moral, ethical, economic and other components is extremely important in determining both the life perspectives of the younger generation and in designing various spheres of social development.

Research Questions

Psychological science presents a sufficient number of studies of the categories “happiness”, “subjective well-being”, most often presented by the subject in social reality in the concept of “good life”. At the same time, empirical studies of perceptions of “good life” determining the vector of destructive self-realization in teenagers at-risk are not actually presented.

Teenagers at-risk are teenagers whose development features can create an increased risk of deviating behaviour ( Belobrykina & Limonchenko, 2019; Bordovsky, Kazakova, & Gorokhovatskaya, 2001). The results of this study revealed that teenagers inclined to deviant behaviour have a specific view of “good life”, the differentiating sign of which in their view is entertainment; Material wealth giving an opportunity to feel superiority over others; Freedom, understood as a lack of obligations. Along with the devaluation of the emotional component of life, they are characterized by a conscious rejection of cultural congruence and the choice of a criminal system of coordinate for self-realization. The revealed peculiarities of perceptions of “good life” in teenagers group at risk provide an opportunity to individualize and optimize the psycho-correction work of the school psychologist and social teacher in regard to deviant teenagers.

Purpose of the Study

We find it extremely important to study the idea of good life in teenagers at risk of forming deviant behavior, as it is these ideas, in our view, that play a key role in choosing the option of self-realization of the individual during the period of becoming an attractive life strategy.

Research Methods

The value orientations and life perspectives of teenagers at-risk also have their own specifics ( Feldstein, 2008; Koshenova, 2016; Schneider, 2015; Belobrykina & Limonchenko, 2017), but even if in form they are identical to the values and probabilistic plans characteristic of teenagers with socially acceptable behaviour, in meaningful content they will probably be fundamentally different, which will naturally affect the system of their perceptions of good life. This determined the direction of our empirical research, which has a pilot nature, involving 80 students of comprehensive school. Of these, 40 respondents are teenagers of under control group at risk of forming deviant behaviour and 40 are teenagers of the conditional norm of behaviour. The range of age limits of the subjects was 12-16 years old.

Due to the lack of diagnostic tools on the subject under study, research procedures developed by us in the framework of the ideographic approach and modified from among the available techniques were used:

The author’s modification of the “Unfinished Sentences” technique, including 9 unfinished sentences (e.g. Good life is...; I want to live well because...; For life to be good, it’s necessary...; etc.).

The analysis of empirical data was carried out in two directions: quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative analysis allows determining the proportion of individual values in the understanding of the category “good life” and the average for each group of subjects. Qualitative analysis allows determining the content of the concept by indicators differentiated based on the application of a content-analytical approach.

The author’s technique “Arranging” aimed at identifying and arranging the valuable components of “good life”.

Respondents are invited to choose from the general list the important, in their opinion, components of “good life” and then arrange them according to the degree of subjective significance. The starting “valuable components” are 26 reference words-concepts (for example, Freedom, Power, Money, Family, Work, Happiness, etc.). It is allowed to include in the given list your own variants of answers, the number of which is not limited.

Mini-essay on “A good life for me is....”. The technique is aimed at identifying meaningful components of the category “good life”.

Findings

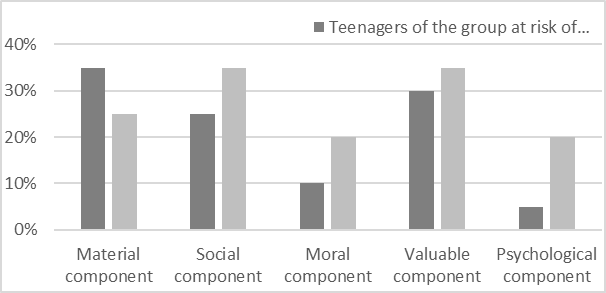

The accuracy of the differences was assessed using the Mann-Whitney’s U-criterion. The results, the significance of which did not exceed the level of 0.05%, were recognized as reliable. The graphical representation of the data obtained in the research is shown in Fig.

According to the data of the technique “Unfinished sentences” (Figure

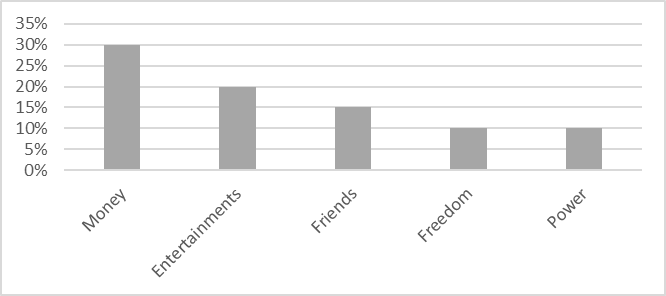

The results obtained according to the technique “Arranging” (Fig.

Fig.

Statistically significant differences in the comparison of subject according to the “Arranging” technique are recorded by such value components of good life as “friends” (Uemp = 311,000 at p = 0.000), “family” (Uemp = 162,000 at p = 0.000), “freedom” (Uemp = 342,000 at p = 0.000), “entertainment” (Uemp = 298,000 at p = 0.000), “power” (Uemp = 401,000 at p = 0.000), “health” (Uemp = 251,000 at p = 0.000), “love” (Uemp = 273,000 at p = 0.000) and “education” (Uemp = 149,000 at p = 0.000). The indicator “money” is equally significant for teenagers of both groups (statistically significant differences are not revealed).

A rather disturbing indicator which shows serious gaps in the modern system of education implemented by the institutions of primary socialization (family, kindergarten, school), in our opinion, is the fact that the categories “culture”, “morality” were not included in the list of value orientations of good life in both groups of subjects. It is also noteworthy that the lack of choice of categories “well-being of surrounding people”, “work”, “favourite business” by teenagers with normative behaviour, is not consistent with the data on the method “Unfinished sentences”. It can be assumed that due to the reposting of the technique in the Internet and its frequent usage in educational institutions, subjects with social and normative behaviour could demonstrate a tendency to position socially desirable answers.

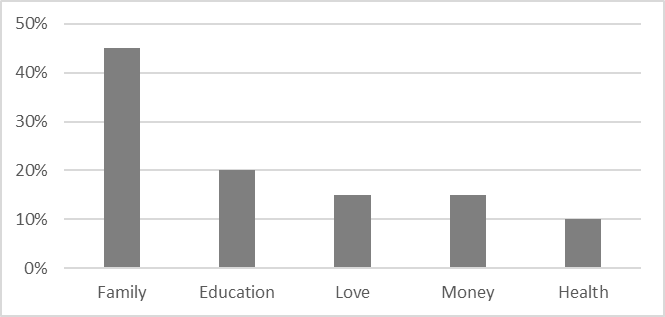

The analysis of the data obtained from the mini-essay “A good life for me is...” (Fig.

The analysis of the obtained data revealed the specificity of perceptions of good life among teenagers of the group at risk of deviant behaviour formation. On the one hand, the assessment of the validity of the differences in the technique “Unfinished sentences” suggests that the material component, including financial independence, success and power, is equally significant in the structure of the category “good life” for teenagers of our empirical sample, regardless of the presence of the risk of deviant behaviour. On the other hand, qualitative analysis of the data has shown that although both groups of teenagers indicate the material component for granted, the teenagers of the group at risk do not indicate how this goal can be achieved in detail (except in illegal ways, for example, “it must be stolen”). The semantic load of the answers of teenagers with social and normative behaviour, on the contrary, differs by the designation of specific conditions - good work, which would contribute to obtaining good wages; the need to work conscientiously to achieve the goal of a good life.

It is important to note that among teenagers of the group at risk the “value” component, unlike among teenagers with socially acceptable behaviour, dominates material values (“when there is a lot of money”, “to have a cool car”, “it is money and power”), hedonistic orientation (“to enjoy”, “this life is better and cooler than others have”) and self-centric setting (“nothing can be denied to yourself”, for the sake of your own wishes you can go too far”). Despite the fact that teenagers with social and normative behaviour have the value of their own well-being (“I want to live better than others”, “I aspire to a good life”), the qualitative difference is that they note the importance and well-being of the people around them, thus demonstrating not only the focus on themselves, but also the orientation on others (“...my well-being, happiness of relatives”, “good life cannot be without happiness of myself and people around me”), indicating the importance of working life for achieving good life.

Analysis of the content by the criterion “social component of good life” in teenagers at risk group showed the importance of “having loyal friends” able to provide all kinds of support, as well as the prevalence of the importance of respect and recognition by others (“…When everyone respects me…”, “to be known, respected, to be known”), which, however, do not imply reciprocity - identical on the part of a teenager to others, and are positioned without indicating the means and ways of achievement.

For teenagers with social and normative behaviour, the content of the social determinant of good life is expressed, first of all, in the importance of mutual respect with others, with peers (“…when you are respected and you respect”), good relations in the family (“…when you do not fight with your mother”, “relations in the family and with parents are important”), the presence of true friends and comrades.

Qualitative differences are also recorded by the indicator of the moral component of good life. It has been found that most responses of teenagers of the group at risk do not imply the significance of moral principles and do not reflect the true moral content (“it is necessary to be persistent, brazen in achieving the goals”, “it is necessary to receive everything by any means”). Teenagers with socially acceptable behaviour are characterized by reliance on moral norms in perceptions of a good life (“…cannot be without adequate behaviour in society”; “cannot be without freedom within the frames”, “…pure conscience”).

The analysis of the expression of the psychological component of good life showed insufficient relevance of this component for teenagers of the group at risk of deviant behaviour. For teenagers with socially normative behaviour prevails positive emotional states, experiences (“…when nothing worries”, “… it suggests a positive mood”, “…good fortune”, “… it cannot be without love”) - both their own and other people’s.

Qualitative analysis of empirical data obtained by the “Arranging” technique has revealed very informative facts. It has been established that the category of freedom is understood by teenagers of a group at risk to be predominantly permissive, the absence of a regulatory framework that may in any way limit the activities, behaviour or means of realizing their current and potential needs. Teenagers with a conditional norm of behaviour understand that freedom has certain limits in permissiveness and implies a measure of responsibility for any “free” choice.

It has been revealed that for teenagers of both groups the most important components for good life were “money, success”. However, teenagers with socially acceptable behaviour noted more often the importance of financial wealth as the result of work (“to be able to provide for themselves and their loved ones”, “to find a good job and to afford a lot”). Teenagers of a group at risk by advantage indicated money simply as a component, without indicating the ways of achieving them (for example, “money, friends are near...”, “…a lot of money”). These results are generally consistent with the “Unfinished sentences” technique.

No less important component of good life in two groups of subjects “family” was marked and for teenagers with social and normative behaviour it is significant not just the presence of a family, but the well-being of it and all relatives (“…when I am happy and my family is too”, “…the well-being of my family”, “…my family and friends are in a good condition”).

The importance of the component “true friends” is also recorded in both groups of teenagers, but in the group at risk of deviant behaviour this category is more often marked by criminal argo words (“…my bros are near”, “to spend time with my bros”).

An important component of “good life” for teenagers are “education, study, self-development”, moreover among teenagers with social and normative behaviour this component (“…good education and then good work”, “have finished studying to get prestigious work”) is more than twice as high as among teenagers of a group at risk, whose position was also stable (“…to finish school well”).

“Life is better than others” was also considered important by teenagers of both groups, but in different volume and with different sense emphasis. For example, teenagers at-risk are more characterized by the formal designation that they want to live better than most (“when everything is good for me”, “life is better than those around me”). Teenagers with social and standard behaviour noted that for good life it is necessary to work, work much (“good work and the status”, “…what it is necessary to aspire to not to live as many”).

“Free time, hobby” also entered the category of significant components of good life, but proved to be more significant for the group at risk. The meaning context of this component for teenagers with social and normative behaviour is characterized by the description of their favourite activities (“reading books”, “programming”, “modelling”, “playing sports”, “doing their favourite business”), while teenagers of the group at risk more designated their free time as freedom from duties, tasks, norms and rules.

“Love” was treated more significant for good life by teenagers with pro-social behaviour whereas a component “freedom, independence” meets twice more often at teenagers of group at risk who treat it as independence in actions, deeds, freedom from parents’ “moralizing”. For teenagers of social norm, freedom and independence mean, first of all, something necessary for the development and realization of the right of choice, having the limits of permissiveness.

In general, the analysis of data of mini-assays showed that for teenagers at risk of deviant behaviour, “money”, “success”, “true friends”, “free time” and “independence” are the highest priorities for good life. Teenagers with normative behaviour consider “family”, “education”, “self-development” and “love” as the most important ones.

Conclusion

Thus, it is possible to note that at the level of a pilot research qualitative and statistical differences in structure and content of ideas of “good life” at teenagers at risk in comparison with the teenagers who are characterized by social and normative behaviour are revealed.

Understanding by teenagers at risk of forming of deviant behaviour of category «good life» is characterized by dominance of the material and hedonistic components, orientation to the power and superiority over people around, to freedom and independence which are expressed in denial of norms and rules.

The received results have theoretical and applied relevance as they allow planning perspectives of further researches.

The revealed features of ideas of good life at teenagers at risk give the chance to individualize and optimize psycho-correctional work of the school psychologist and social teacher concerning deviant teenagers.

Acknowledgments

The work is carried out according to the Russian Government Program of Competitive Growth of Kazan Federal University.

References

- Bayanova, L. F., & Minyaev, O. G. (2018). Vliyanie kul'turnoj kongruentnosti na lichnostnye svojstva podrostkov [Cultural congruence influence on the personal properties of adolescents]. Kazanskij pedagogicheskij zhurnal [Каzan Pedagogical Journal], 6(131), 192-195.

- Belobrykina, O. A., & Limonchenko, R. A. (2017). Osobennosti perezhivaniya psihologicheskih problem deviantnymi podrostkami [Features of experiencing psychological problems in deviant adolescents]. Nacional'nyj psihologicheskij zhurnal [National Psychological Journal], 4(28), 129-138. Retrieved from http://npsyj.ru/articles/detail.php?article=7315

- Belobrykina, O. A., & Limonchenko, R. A. (2019). Social'no-psihologicheskij profil' podrostka s povedencheskimi narusheniyami [A social and psychological profile of the teenager with violations in behaviour]. In O.A. Belobrykina (Eds.), Sovremennaya social'naya real'nost': vyzovy, riski, perspektivy: monografiya [In Modern social reality: challenges, risks, prospects] (pp. 100 – 116). Novosibirsk: Izd-vo NGPU.

- Bordovsky, G. A., Kazakova, E. I., & Gorokhovatskaya, N. V. (Eds.). (2001). Deti “gruppy riska”: Materialy mezhdunarodnoj konferencii [Children at risk: Proceedings of the international conference]. St. Petersburg: Russian GPU of A.I. Herzen.

- Diener, E., & Ryan, K. (2009). Subjective well-being: A general overview. South African Journal of Psychology, 39(4), 391-406. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/008124630903900402

- Djidaryan, I. A. (2013). Psihologiya schast'ya i optimizma [Psychology of happiness and optimism]. Moscow: Izd-vo IP RAN.

- Easterlin, R. (2006). Life Cycle Happiness and its Sources: Intersections of Psychology, Economics and Demography. Journal of Economic Psychology, 27(4), 463-482.

- Feldstein, D. I. (2008). Trudnyj podrostok: nekotorye psihologicheskie voprosy formirovaniya lichnosti detej podrostkovogo vozrasta [A Difficult Teenager: Some Psychological Issues of Personality Formation of Adolescent Children]. Moscow: Moskovskij Psihologo-social'nyj Institut.

- Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Karapetyan, L. V. (2014). Teoreticheskie podhody k ponimaniyu sub"ektivnogo blagopoluchiya [Theoretical approaches to understanding of subjective well-being]. Izvestiya Ural'skogo federal'nogo universiteta. Ser. 1. Problemy obrazovaniya, nauki i kul'tury [Izvestia Ural Federal University. Journal. Series 1. Issues in Education, Science and Culture], 1(123), 171-182.

- Koshenova, M. I. (2019). Neskromnoe obayanie nasiliya: v zhanre nauchnogo esse [The immodest charm of violence: In the genre of scientific essay]. PEM: Psychology. Educology. Medicine, 1, 119-127. Retrieved from pem.esrae.ru/24-252

- Koshenova, M. I. (2016). “Problemnye zony” sohraneniya psihologicheskogo i social'nogo zdorov'ya shkol'nikov v period podrostnichestva [“Problem zones” of preservation of psychological and social health of school students in the period of a podrostnichestvo]. In M.G. Chuhrova & O.A. Belobrykina (Eds.), Innovacii v medicine, psihologii i pedagogike: Materialy VII Mezhdunarodnoj nauchno-prakticheskoj konferencii (V'etnam, Muj Ne) [Innovations in Psychology, Pedagogy & Medicine: Proceedings of the VII International Academic Conference (Vietnam, Mui Ne)] (pp. 229-234). Novosibirsk: Nemo Press.

- Rezazadeh, Z., & Bayanova, L. F. (2017) Obuslovlennost' psihicheskih sostoyanij moral'noj normativnost'yu [Conditionality of mental states with moral normativity]. Psihologicheskie issledovaniya: elektronnyj nauchnyj zhurnal [Psikhologicheskie Issledovaniya], 10(53), 10-22. Retrieved from http://psystudy.ru

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Schneider, L. B. (2015). Psihologiya podrostkovoj deviantnosti i addiktivnosti [Psychology of adolescent deviancy and addictivity]. Moscow: Moskovskij Psihologo-social'nyj Universitet.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: a visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Free Press, Simon & Schuster.

- Shamionov, R. M. (2008). Sub"ektivnoe blagopoluchie lichnosti: psihologicheskaya kartina i faktory: monografiya [Subjective well-being of personality: a psychological pattern and factors]. Saratov: Nauchnaya kniga.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

23 January 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-077-8

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

78

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-838

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques

Cite this article as:

Bayanova*, L. F., Belobrykina, O. A., & Koshenova, M. I. (2020). Perceptions Of “Good Life” Of Teenagers Inclined To Deviant Behavior. In R. Valeeva (Ed.), Teacher Education- IFTE 2019, vol 78. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 587-596). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.01.64