Perception Of Intergenerational Relationships By People With Different Types Of Generational Identification

Abstract

The article discusses an actual problem of intergenerational relationships. The authors analyze the subjective factors of intergenerational interaction, which include stereotypes of perception of generations. Based on theories of social identity and self-categorization, it is concluded that the relationship between representatives of different generations may depend on the peculiarities of perception of one’s own belonging to one of them and opposing oneself to other generations. The study is aimed at identifying the dependence of the perception of intergenerational relations on the type of generational identification. In the study, 146 people were surveyed (66 men and 80 women aged 17 to 72 years). Significant differences were obtained for the perception of the relations of the generation with representatives of the post-war (scales: proximity and mutual understanding), Soviet (scales: comfort, proximity, lack of conflict, mutual understanding), transitional (scales: comfort and tranquility) and post-Soviet (scales: comfort, proximity, tranquility) generations. On the basis of the data obtained, it was concluded that: the least favorable relationships develop between the Soviet and post-Soviet generations; the most controversial attitude in the society develops towards the representatives of the Soviet generation; the greatest degree of misunderstanding between generations is noted in relations with the post-Soviet generation; people who identify themselves with the transitional generation characterize a more negative relationships within the group versus outside the group; the most favorable relationships develop between the older (post-war and Soviet) and younger (transitional and post-Soviet) generations. The article discusses the limitations of the research and outlines its future prospects.

Keywords: Generational identitypost-war generationSoviettransitional

Introduction

The problem of intergenerational relationships is a sphere of social life that requires scientific study. Demographic changes in the society associated with an increase in the number of older people relative to other age groups noted throughout the world, lead to the fact that modern society is becoming multi-generational. In modern society, generations coexist that have a huge age gap (from 0 to 100 years) and are completely different, since each of them has its own social context, was formed during different cultural and historical events and has a different mindset. Multi-generational interaction is an important part of the lives of millions of modern people, even in societies where their cohabitation is not a norm (Easthope, Liu, Burnley, & Judd, 2017). These trends lead to the exacerbation of communication problems between the representatives of different generations. Foreign (Venter, 2017) and Russian researchers (Barsukov, 2018; Guseltseva, 2017) speak about the conflict or gap between the generations.

After analyzing the problems in intergenerational interaction, the authors learn that their causes lie in objective and subjective factors. For example, some researchers believe that the conflict between the generations may be based on the differences in the ways of communication with other people. First of all, it concerns the use of information and communication technologies (Kadylak et al., 2018; Venter, 2017). The subjective causes of intergenerational conflicts are the perception stereotypes of generations (Urick, Hollensbe, Masterson, & Lyons, 2017; Van Rossem, 2018).

In our study, we want to address the subjective factors of intergenerational interaction, since the perception of one’s own and other generations mediates the interaction between people (Van Rossem, 2018; Patel, Tinker, & Corna, 2018).

Problem Statement

While the academicians argue the existence of the generation effects (Urick, 2014; Cucina, Byle, Martin, Peyton, & Gast, 2018), researchers recognize the existence of stable stereotypes of generations (Patel et al., 2018; Manzi et al., 2018) and focus their efforts on their study.

Urick et al. (2017) and his colleagues studied the role of the perception of another person in the formation of intergenerational conflict. They concluded that the intergenerational conflict is caused by stereotypes of the perception of values and behaviors of other generations (Urick et al., 2017). A number of researchers believe that stereotypes related to age have an obvious influence on the perception of other people and themselves (because they are related to generational identity), and also open the way to understanding differences between generations (Parry & Urwin, 2017; Lyons & Schweitzer, 2017).

Kolarova, Bediova, and Rasticova (2016) note that communication problems between representatives of different generations are aggravated due to the lack of sympathy on both sides, lack of understanding of each other’s lifestyle. Kadylak et al. (2018) with colleagues found that the use of a mobile phone during face-to-face communication in the family was perceived by the elders as an insult and evidence of inattention.

It should be noted that most of the studies above rely on objective criteria for the differentiation of generations (year of birth/age). Such approach to research is criticized (Costanza & Finkelstein, 2015; Campbell, Campbell, Siedor, & Twenge, 2015) and requires a search for alternatives. Some studies have shown that age cohorts are distinguished by a variety of orientations to prototype generations (Lyons & Schweitzer, 2017), while the age stereotypes are associated with personal identity (Urick, 2014). This allows suggesting that the perception of intergenerational relations will depend on the generation with which the person identifies himself. Previously, it was found that generation-based identification can increase competitiveness in working relationships (Desmette & Gaillard, 2008) and affect the choice of behavior strategies in a conflict (Ho & Yeung, 2019).

Research Questions

The subject of the study were the differences in the perception of intergenerational relationships in people with different types of generational identification. The identity of generations is viewed as a person’s understanding of their membership in a group of generations (Joshi, Dencker, Franz, & Martocchio, 2010). The above-mentioned studies show that there are differences between people of different ages in the perception of generations and the relations between them. They suggest that the differences in the perception of intergenerational interaction will also be different in people who identify themselves with a certain generation based on common values and experience. Therefore, in a study of intergenerational relations, it is appropriate to use identity theories, such as social identity theory and self-classification.

The social identity is conceptualized as a membership in social groups, which is given emotional and axiological significance (Ho & Yeung, 2019). The theory of social identity suggests that if a person identifies himself with a group, he will behave on the basis of his own ideas about the behavior of this group and stereotypes about other groups singled out on similar grounds (Stockdale & Crosby, 2004). With regard to generations, it can be argued that people will consider themselves to be the generation that is significant to them and will oppose themselves to people belonging to other generations.

The theory of social identity is connected with the theory of self-classification, since both of them explain the mechanisms of intergroup interaction. In the theory of self-classification, it is stated that a person cognizes other people by classifying them into groups and comparing groups among themselves. At the same time, the estimates of groups are asymmetric: their group is rated positively, and the groups of others negatively (Hogg & Rinella, 2019). This explains the barriers that arise in intergenerational communication (Smola & Sutton, 2002).

Unfortunately, there is not enough research in science to assess how generational identification affects the perception of generations in modern Russia.

Purpose of the Study

To identify the dependence of perceptions of intergenerational relations on the type of generational identification.

Research Methods

The study involved 146 people, including 66 men and 80 women. The age of the respondents ranged from 17 to 72 years. The study involved employees of enterprises and organizations of Chelyabinsk (Russia) and students of state universities.

The type of generational identification of respondents was determined by the question of which generation they belong to. The research participants were offered 4 options to choose from: the post-war generation (whose values were formed during the period of the restoration of the USSR after the Second World War); the Soviet generation (whose values were formed in the era of the late USSR); the transitional generation (whose values were formed in the era of perestroika and the collapse of the USSR); the post-Soviet generation (whose values were formed in the era of stabilization of the socio-economic situation in Russia). The selection was limited to one option.

To assess the interaction between the representatives of different generations, semantic scales (comfort/discomfort; proximity/distance; conflict/conflict-free; respect/disrespect; misunderstanding/ understanding; peace of mind/tension) were offered to the participants of the study. For each of the scales, respondents rated the interaction between the representatives of the generations under study in pairs in points from 3 to -3.

For mathematical processing of the research results, the Kruskal-Wallis H-test was used. The calculations implemented IBM SPSS Statistics 23 software package.

Findings

Table

According to the data obtained, the people who identify themselves with the Soviet (35%) and post-Soviet (43%) generations prevail in the study. The share of people identifying themselves with the post-war generation was 12%, and 10% identified themselves with the transitional one.

In our study — as in foreign studies (Lyons & Schweitzer, 2017) — it was found that some people do not identify themselves with the generation to which they can be attributed according to their year of birth. Moreover, in this study, a larger number of them turned out to be in the older age group. This confirms that using the age as the criterion for dividing the pool of respondents is not enough to study generations (Lyons & Schweitzer, 2017; Sivrikova, 2014).

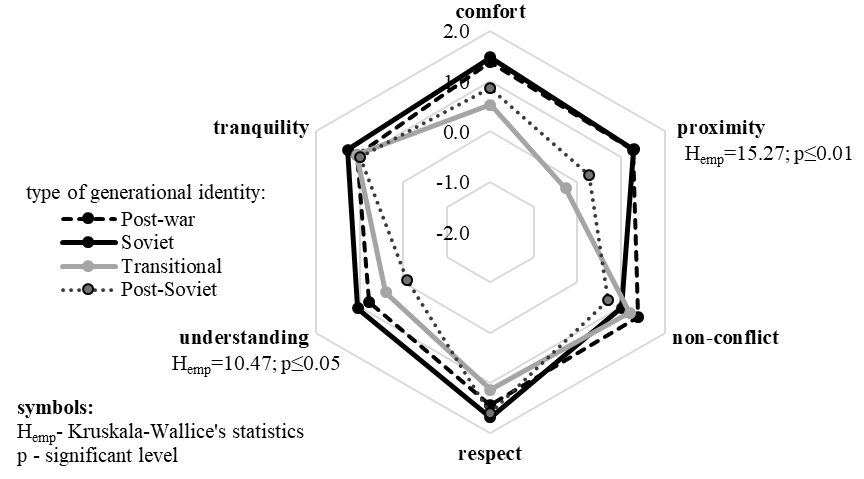

The treatise found that the perception of relationships with the post-war generation depends on the generational identification (Figure

Significant differences were found in the level of assessment of the degree of proximity (p≤0.01) and mutual understanding (p≤0.05) in relations between the representatives of the postwar generation and people identifying themselves with different generations. The most favorable relations with the post-war generation are formed by people who identify themselves with the same or with the Soviet generation.

Those who identify themselves with the post-Soviet generation feel the least degree of understanding with this generation, while those who identify themselves with the transition generation feel the greatest degree of interpersonal distance.

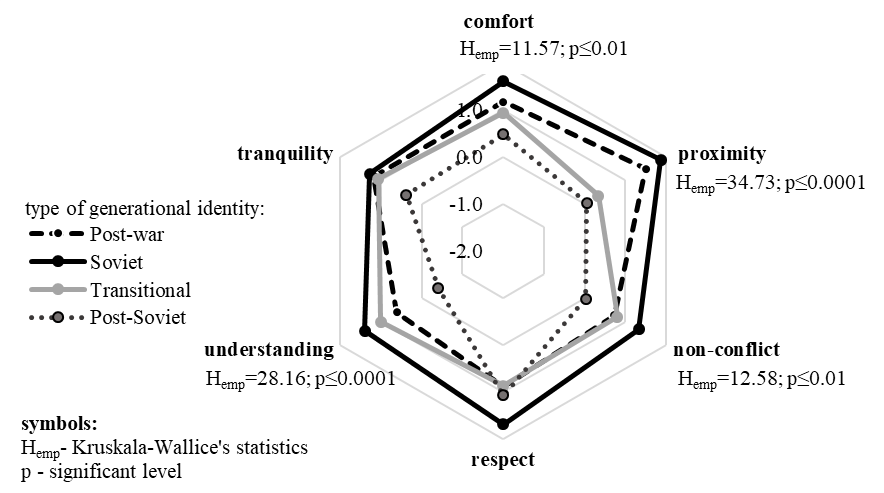

The largest number of significant differences was recorded in the assessment of relations with the Soviet generation in people with different types of generational identification (Figure

As follows from the theory of self-categorization, the most favorable relationships are formed among the representatives of this generation among themselves (within the group). Significant differences were found in the level of comfort (p≤0.01), degree of proximity (p≤0.0001), conflict absence (p≤0.05) and mutual understanding (p≤0.0001). For all these indicators, the smallest values characterize the relationship between the Soviet and post-Soviet generation. This indirectly indicates that the society maintains the stereotype of the opposition of these two generations.

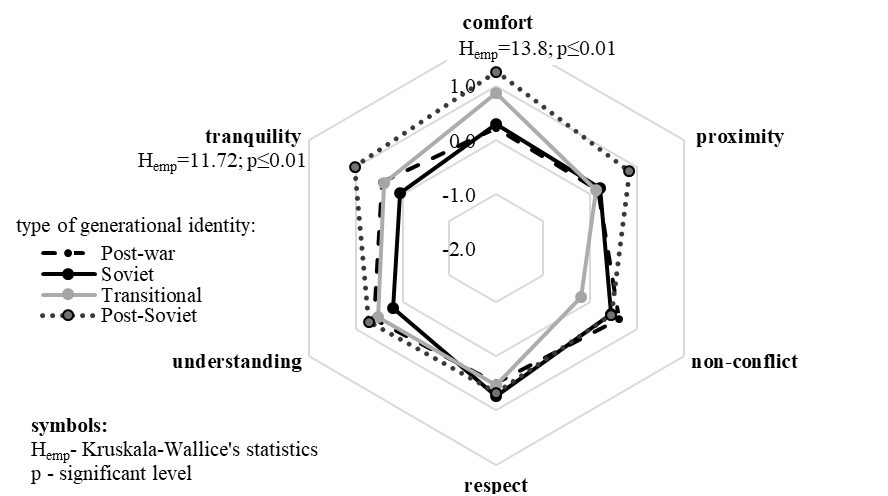

The transitional generation turned out to be the only generation in which relations within the group are less favorable than the relations with the representatives of another group (Figure

Significant were the differences in the assessment of the relationship between the transitional generation and the generation with which respondents identify themselves, according to the scales: comfort (p≤0.001) and tranquility (p≤0.001). The relations with the transitional generation seem to be the most comfortable and tranquility with people identifying themselves with the post-Soviet generation, and the least with the Soviet generation.

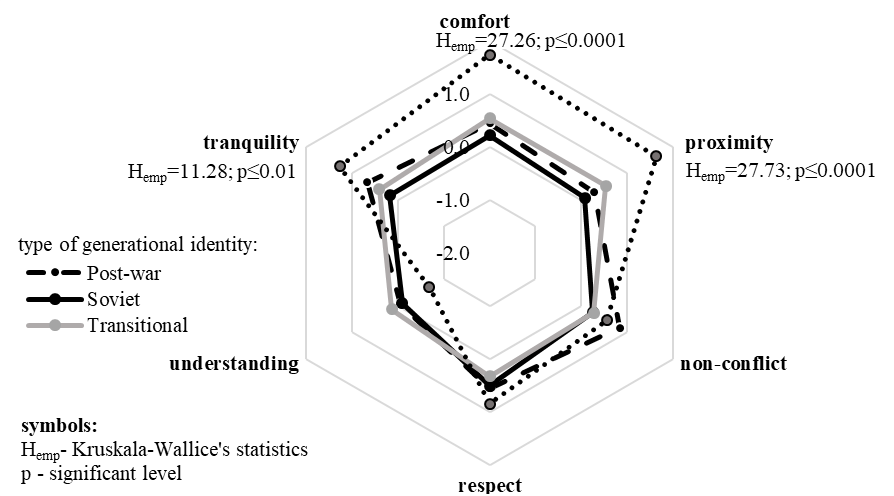

A striking feature of relationships with the post-Soviet generation in the entire sample is the relatively low degree of mutual understanding (Figure

Significant differences are found in the assessments of the relationship of his generation with the post-Soviet generation on such scales as comfort (p≤0.0001), proximity (p≤0,0001) and tranquility (p≤0.01). The most favorable relations with the post-Soviet generation are those who identify with it. The least favorable relationships with the post-Soviet generation are formed by people who identify themselves with the Soviet generation.

Conclusion

The results of the study confirm the hypothesis that the perception of other generations may pose a threat of conflicts between generations (Urick et al., 2017; Kolarova et al., 2016). These studies lead to the following conclusions: 1) the least prosperous relationships are formed between the Soviet and post-Soviet generations. The most controversial attitude in society is formed in assessments of the relationship with the Soviet generation; 2) the relations between the Soviet and post-Soviet generation lie in the zone of increased risk of conflicts arising from the lack of mutual understanding. Intergenerational relations with the post-Soviet generation are characterized by the least degree of mutual understanding; 3) people who identify themselves with the transitional generation characterize a more negative nature of relationships within the group than outside the group; 4) the most favorable relationships develop in the diads of generations “postwar–Soviet” and “transitional–post-Soviet”.

The results of the study can have important consequences, because they show the potential of tension between generations associated with the peculiarities of their perception in society.

The limitations of the findings are related to the research method used and selected pool of respondents. The strict limitation of choice in determining generational identification artificially excluded variants of diffuse identity from the analysis. The need to divide the sample into 4 groups, based on the type of generational identification, led to the disturbance of group equivalence on a variety of demographic characteristics (gender, education), which could lead to a distortion of the research results. At the same time, the conducted research expands the existing data on intergenerational relations in modern Russia.

Acknowledgments

The study was conducted with the financial support of the RFBR. Project No. 18-013-00910 "Dynamics of Generation Values as a Marker of the Transformation of Social Relations in the Russian Society”.

References

- Barsukov, V.N. (2018). Barriers to Social Integration of the Older Generation in the Context of Intergenerational Communication Issues. Economic and social changes-facts trends forecast, 11(5), 214–230.

- Campbell, W., Campbell, S., Siedor, L., & Twenge, J. (2015). Generational differences are real and useful. Industrial and organizational psychology, 8(3), 324–331.

- Costanza, D. P., & Finkelstein, L. M. (2015). Generationally based differences in the workplace: Is there a there there? Industrial and organizational psychology: perspectives on science and practice, 8(3), 308–323.

- Cucina, J. M., Byle, K. A., Martin, N. R., Peyton, S. T., & Gast, I. F. (2018). Generational differences in workplace attitudes and job satisfaction: Lack of sizable differences across cohorts. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 33(3), 246–264.

- Desmette, D., & Gaillard, M. (2008). When a “worker” becomes an “older worker”: The effects of age –related social identity on attitudes towards retirement and work. Career Development International, 13, 168–185.

- Easthope, H., Liu, E., Burnley, I., & Judd, B. (2017). Changing perceptions of family: A study of multigenerational households in Australia. Journal of Sociology, 53(1), 182–200.

- Guseltseva, M. C. (2017). Features of the inter-generational relations in the conditions of transitive society. World of psychology, 1(89), 38–51.

- Ho, H. C. Y., & Yeung, D. Y. (2019). Effects of social identity salience on motivational orientation and conflict strategies in intergenerational conflict. International journal of Psychology, 54(1), 108–116.

- Hogg, M. A., & Rinella, M. J. (2019). Social identities and shared realities. Current opinion in psychology, 23, 6–10.

- Joshi, A., Dencker, J. C., Franz, G., & Martocchio, J. J. (2010). Unpacking Generational Identities in Organizations. Academy of Management Review, 35, 392–414.

- Kadylak, T., Makki, T. W., Francis, J., Cotten, S. R., Rikard, R. V., & Sah, Y. J. (2018). Disrupted copresence: Older adults' views on mobile phone use during face-to-face interactions. Mobile media & communication, 6(3), 331–349

- Kolarova, I., Bediova, M., & Rasticova, M. (2016). Factors influencing motivation of communication between generation Y, generation X and Baby Boomers. In Proceedings of the 17th European conference on knowledge management (рр. 476–484). Kidmore End, Acad Conferences LTD.

- Lyons, S. T., & Schweitzer, L. (2017). A qualitative exploration of generational identity: making sense of young and old in the context of today’s workplace. Work, Aging and Retirement, 3(2), 209–224.

- Manzi, C., Coen, S., Regalia, C., Yevenes, A. M., Giuliani, C., & Vignoles, V. (2018). Being in the Social: a cross-cultural and cross-generational study on identity processes related to Facebook use. Computers in Human Behavior, 80, 81–87.

- Parry, E., & Urwin, P. (2017). The evidence base for generational differences: where do we go from here? Work, Aging and Retirement, 3(2), 140–148.

- Patel, J., Tinker, A., & Corna, L. (2018) Younger workers’ attitudes and perceptions towards older colleagues. Working with Older People, 22(3), 129–138

- Sivrikova, N. V. (2014). Features of social identification of inhabitants of South Ural. In the world of discoveries, 9(57), 322–337.

- Smola, K. W., & Sutton, C. D. (2002). Generational Differences: Revisiting Generational Work Values for the New Millennium. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 363–382.

- Stockdale, M. S., & Crosby, F. J. (2004). The Psychology and Management of Workplace Diversity. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Urick, M. (2014). The presentation of self: dramaturgical theory and generations in organizations. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 12(4), 398–412.

- Urick, M. J., Hollensbe, E. C., Masterson, S. S., & Lyons, S. T. (2017). Understanding and managing intergenerational conflict: An examination of influences and strategies. Work, Aging and Retirement, 3(2), 166–185.

- Van Rossem, A. H. D. (2018). Generations as social categories: An exploratory cognitive study of generational identity and generational stereotypes in a multigenerational workforce. Journal of Organizational Behavior. Retrieved from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/

- Venter, E. (2017). Bridging the communication gap between Generation y and the Baby Boomer generation. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 22(4), 497–507.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

28 December 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-075-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

76

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-3763

Subjects

Sociolinguistics, linguistics, semantics, discourse analysis, science, technology, society

Cite this article as:

Zolotova, I., Artemeva, N., Sokolova, N., Moiseeva, E., & Sivrikova*, N. (2019). Perception Of Intergenerational Relationships By People With Different Types Of Generational Identification. In D. Karim-Sultanovich Bataev, S. Aidievich Gapurov, A. Dogievich Osmaev, V. Khumaidovich Akaev, L. Musaevna Idigova, M. Rukmanovich Ovhadov, A. Ruslanovich Salgiriev, & M. Muslamovna Betilmerzaeva (Eds.), Social and Cultural Transformations in the Context of Modern Globalism, vol 76. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 2926-2934). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.12.04.394