Abstract

The dynamics of the field of social tension in the student environment is analyzed. The object are students of several Moscow universities: from Moscow and Moscow region - 19%, the North Caucasus - 10%, the European part of Russia - 54%, Siberia - 13%, the Far East - 3%, the Far North –1%. The monitoring was carried out since 2010 till February 2019. About 250 students studying at information technology, management, sociology, economics, environment studies, psychology, linguistics, and physical culture departments were surveyed. These students are representatives of Millennials / Y Generation and Centenals / Z Generation. Within the original model of the “

Keywords: Social tensionrelative deprivationfrustrationaggression

Introduction

The main productive factor of intensive socio-economic modernization of the modern state is human capital. One of the key socio-psychological characteristics of human capital is the state of mass consciousness. In the 2000s, Russia avoided radical political and economic reforms. The ongoing social changes are associated with “generational” shifts.

The most active part of the population, along with representatives of X generation (Howe & Strauss, 2000; Brosdahl & Carpenter, 2011) is Millennial / Y Generation born mostly in 1982-2000. This first “digital generation” (digital natives) is immersed in social networks (Bennett, Maton, & Kervin, 2008; Manheim, 2000). Z generation born in the 2000s behave in a similar way (Radaev, 2018). Human resources, a spiritual sphere, social tension in the youth environment during the most “impressionable period of life” have a fundamental formative effect on their lives (Krosnick & Alwin, 1989). It is important to study the social well-being of students who are most susceptible to social changes. If economic aspects of human resources are in the focus of attention of domestic researchers, the socio-psychological one remain on the periphery of public interest.

Problem Statement

Feelings of students are a powerful potential for social development (Simonyan, 2018). Inherent characteristics of modern Russian society are a high degree of politicization and social tension. The study of emotions and behavior of young people involves analysis of factors that transform their emotional states into behavioral acts, including destructive ones. In modern interpretations, emotional tension caused by frustration or relative deprivation and aggression are viewed as correlates (Anderson & Bushman, 2002; From, 2016; Schellenberg, 1996; Dollard, Miller, Doob, Mower, & Sears, 1998). There is no generally accepted view on differences in frustration and relative deprivation. Based on the analysis of aspirations and expectations carried out by J. Frank, K. Levin, and F. Robaier, attempts are made to distinguish these concepts (as cited in Urnov, 2008). Aggression operationalizes social tensions (Borodkin & Volodina, 1997). The field of social tension is a basis for studies on the social dynamics of modern societies (Sztompka, 2005; Grigas, 2004). The diagnosis of social tension is carried out at a qualitative level. Oopportunities for building an effective mechanism for managing risks of social excesses in the student environment requires quantitative assessments of social tension indicators.

Research Questions

The research subject is the dynamics of the field of social tension in the student environment. Despite the objective complexity of formalization, it is possible to monitor and predict probabilities of an increase in social tension in society using mathematical methods. This can be done within the “RDF-effect” model, including the hierarchy of life priorities, frustration and relative deprivation of actors (Orlik, 2008). Following Urnov (2008), frustration (

The research object is students of several Moscow universities from Moscow and Moscow region - 19%, the North Caucasus - 10%, the European part of Russia - 54%, Siberia - 13%, the Far East - 3%, and the High North –1%. The monitoring was carried out since 2010 till February 2019. About 300 students studying at various departments were surveyed. These are representatives of the millennials / Y generation Y and the centenials / Z generation.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the research is to analyze of the dynamics and predict transformation of the emotional state of students into social excesses induced by relative deprivation and frustration by priority life values.

Research Methods

The research methods will be described based on the classification by B.G. Ananyev (as cited in Borytko, 2006).

These are organizational methods (comparative and longitudinal). The annual ten-year mass survey involved work with the same student contingent throughout four years of their undergraduate studies which made it possible to trace the dynamics of the issue.

Respondents evaluated value priorities

Psychodiagnostic methods (surveys, interviews and conversations) were used.

Empirical processing of the results included automated express diagnostics of levels of social tension in two dimensions: value priorities

To identify value priorities, original modification of the algorithm for building a matrix of pairwise comparisons was used in the MPRIORITY 1.0.

Respondents were classified by four levels of social tension. The first level is formed using the peripheral triple of priorities in the hierarchy of value preferences and the low level of the average value of relative deprivation and frustration in the range from 1 to 4. These are

On the basis of fuzzy relation clustering algorithm, the levels of social tension in the student environment were clustered in the MS VBA environment.

Probabilities of aggressive responses to the

Findings

The monitoring of changes in the field of social tension identified several reference points in the minds of students. First of all, these are inter-ethnic clashes which transformed into riots in Moscow in December 2010. Second, these are mass protests which began after the falsification (according to the opinion of participants) of State Duma election results in December 2011. Two multi-thousand rallies were held in December 2011 and February 2012. After the March actions, there was a decline in protest activity. The May campaign was a final point. Third, the annexation of the Crimea generated a massive upsurge of enthusiasm. However, social optimism declined after the 2016 elections to the State Duma. Fourth, since October 2018, discontent has been growing. Intra-family concerns about the retirement age exacerbated by economic problems have been transmitted to the youth environment.

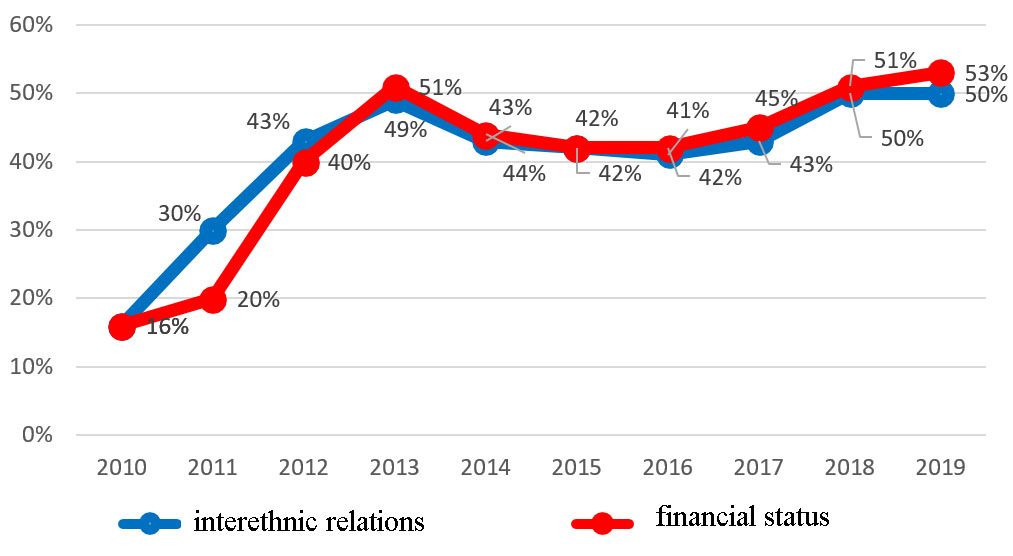

In the context of these events, the following mood dynamics was observed for the categories “interethnic relations” and “financial status”. The observation data are presented in Table

In January 2010, the probability of social excesses induced by relative deprivation and frustration in the category “interethnic relations” was at a low level of 0.16. In January 2011, the probability increased up to 0.3 due to resonant events in Moscow in December 2010. The local maximum of probability (0.49) was reached in October 2013. In October 2014, the probability decreased to 0.42. Tactor of the Crimea ceased to play its unifying role. In 2018, probability of social excesses increased up to 0.5 which is the level of October 2011.

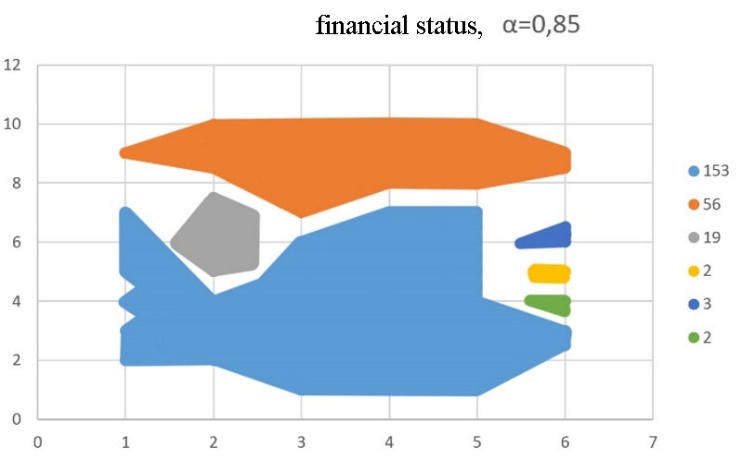

The response to financial changes was growing from the same probability index of 0.16 and in the same periods as the response to interethnic relations. It reached its first local maximum of 0.51 in 2013, equal to the second local maximum in December 2018. In January 2019, it increased up to 0.53 (Figure

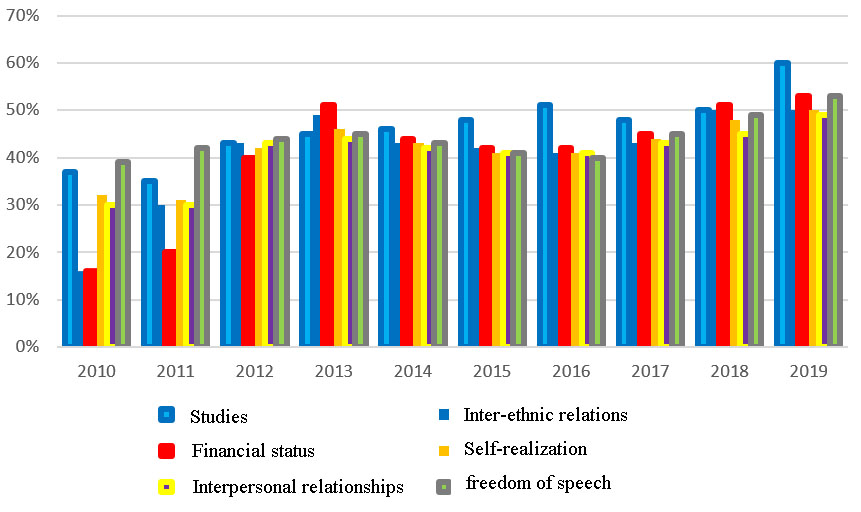

In 2010, probability of an aggressive response to

Similar trends were identified for the categories “self-realization, interpersonal relations and freedom of speech”.

Probability of an aggressive response to the average value of relative deprivation and frustration for all six categories of values is presented in Table

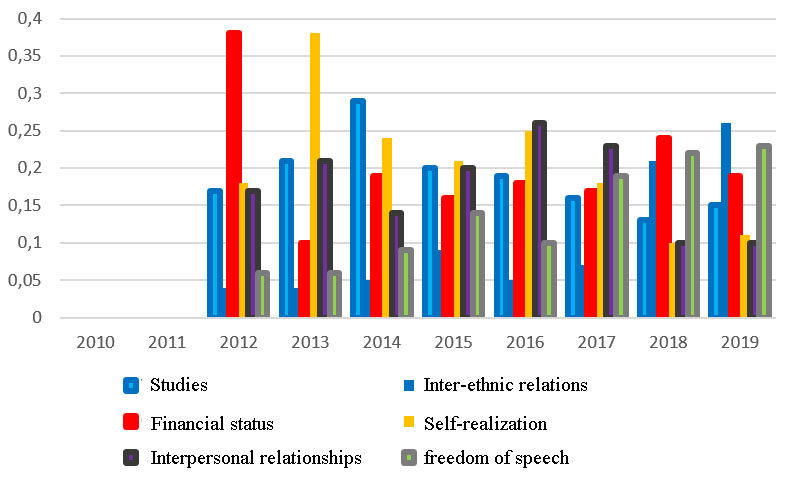

The dynamics of priorities in the hierarchy of values is presented in Figure

In 2012, for the largest number of students (38%), their financial status was the highest value priority, while freedom of speech was the least important value (5%). In December 2018, the financial status was a priority value for 24%. Interethnic relations were a priority value for 21%, freedom of speech – for 22.%. In January 2019, more than 25% of students argued that interethnic relations were a priority value. Freedom of speech was a priority value for 23%. The level of priority of freedom of speech began to grow in 2014 due to the growing number of criminal cases initiated against reposts and likes. Students are sensitive to information on Internet bans.

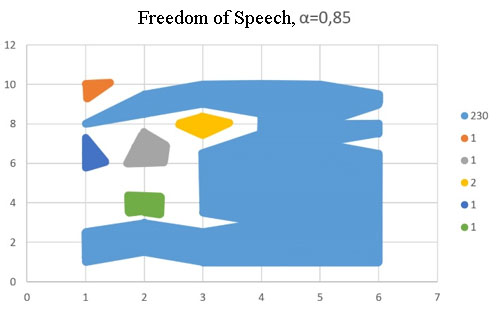

Quantitative data on the distribution of students by levels of social tension were obtained using the clustering methods. The examples of these clusters are presented in Figures

Conclusion

The work focused on software implementation and analysis of the field of social tension in the student environment induced by relative deprivation and frustration based on six categories of value priorities. Indicators of the field of social tension - intensity levels

References

- Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2002). Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 27–51.

- Bennett, S., Maton, K., & Kervin, L. (2008). The ‘digital natives’ debate: a critical review of the evidence. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39(5), 775–786.

- Borodkin, O. B., & Volodina, N. P. (1997). Social tensions and aggression. World of Russia, 4, 107–150.

- Borytko, N. M. (2006). Methodology and methods of psychological and pedagogical research: humanitarianholistic approach. Volgograd: Puplishing house of the All-Union State University of Arts.

- Brosdahl, D. J., & Carpenter, J. M. (2011). Shopping orientations of US males: a generational cohort comparison. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 18, 548–554.

- Dollard, J., Miller, N., Doob, L. W., Mower, O. H., & Sears, R. R. (1998). Frustration and Aggression. London: Routledge.

- From, E. (2016). Anatomy of human destructiveness. Moscow: AST Publishers.

- Grigas, R. (2004). The Outlines of Sociological Conception of the Fields of Social Tensions. Sociological Studies, 4, 29–34.

- Howe, N., & Strauss, W. (2000). Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation. New York: Vintage Books.

- Krosnick, J. A., & Alwin, D. F. (1989). Aging and Susceptibility to Attitude Change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 416–425.

- Manheim, K. (2000). The Problem of Generations. In: Manheim K. Essays on the sociology of knowledge. Moscow: INION of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

- Orlik, L. K. (2008). Probabilistic multiplicative model of an aggressive response to frustration and relative deprivation. Scientific notes of Russian State Social University, 6(62), 159–167.

- Orlik, L. K., Laptev, G. I., Lapteva, N. A., & Kramer, Ya. S. (2016). Social density in the student environment: diagnostics and trends. Social policy and sociology, 2(4-2), 146–155.

- Radaev, V. V. (2018). Millennials compared to previous generations: an empirical analysis. Sociological Studies, 3, 15–33.

- Schellenberg, J. A. (1996). Conflict Resolution. Theory, Research, and Practice. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Simonyan, R. Kh. (2018). Student youth of the border regions Russia Sociological Studies, 4, 82–89.

- Sztompka, P. (2005). Sociology. Analysis of modern society. Trans. C.M. Chervonnaya. Moscow: Logos.

- Urnov, M. Yu. (2008). Emotions in Political Behavior. Moscow: Aspect Press.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

28 December 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-075-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

76

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-3763

Subjects

Sociolinguistics, linguistics, semantics, discourse analysis, science, technology, society

Cite this article as:

Orlik*, L., Zhukova, G., & Kagirova, D. (2019). Social Tension Field In Student Environment In Terms Of Frustration And Deprivation. In D. Karim-Sultanovich Bataev, S. Aidievich Gapurov, A. Dogievich Osmaev, V. Khumaidovich Akaev, L. Musaevna Idigova, M. Rukmanovich Ovhadov, A. Ruslanovich Salgiriev, & M. Muslamovna Betilmerzaeva (Eds.), Social and Cultural Transformations in the Context of Modern Globalism, vol 76. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 2536-2543). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.12.04.340