Abstract

The current research is devoted to finding out what lifestyle and self-esteem levels dominate among east Latvian financial institution managers for solving work and life problems. 23 respondents aged 25 to 33 participated in the study. This age is characterised by dynamics in the perception of the world and the ability to adapt to new life situations, as well as the ability and desire to act in accordance with the modern requirements. Kern “Lifestyle Scale” (KLS) and S.A. Budassi test “Quantitative Expression of Self-esteem” were used. It was found that two lifestyle and self-esteem level combinations prevail: the Victim lifestyle related to low self-esteem and the Perfectionist lifestyle related to high self-esteem. As a result of the study, the authors state that determining a lifestyle type helps understanding the individual traits of the managers, their principles of organising communication and cooperation with colleagues. Adequate self-esteem provides the opportunity to promote employees’ personal growth and quality of life, and improve the participation of managers in professional work. The authors also describe personality type features and suggest taking into account behavioural features in problem situations to mitigate possible confrontations in workplace relationships.

Keywords: Financial institution managerlifestyleself-esteem

Introduction

Variation is observed in determining the factors for improving company employee work performance. Let us review the most popular ones in the latest years. Today, an important direction in the study of work organisation is balance and flexibility in the use of working time, wellbeing in private life, stress at work (Fan & Smith, 2018; Shagvaliyeva & Yazdanifard, 2014). Research into the quality of life and satisfaction levels in people of the pre-retirement age and those aged 65 is gaining popularity, focusing on the feeling of life satisfaction (González-Celis, Chávez-Becerra, Maldonado-Saucedo, Vidaña-Gaytán, & Magallanes-Rodríguez, 2016; Wong, 2019). Studying the lifestyle of representatives of different professions is also popular, taking into account their individual activity style (Fan & Smith, 2017), as well as the peculiarities of the inclusion of migrants in the working and social environment (Shamionov, Grigoryeva, & Usova, 2013; Vallejo Martin & Moreno-Jimenez, 2012). Learning style peculiarities and youth identity is also interesting, as well as mental health in relation to success later in life and at work (Alavi & Toozandehjani, 2017; Chang, Hsiao, & Chen, 2019; Zhang, Quan, Huang, & Kuo, 2017). A specialist’s success depends not only on “successful personality”, but also in part on finding the best niche (Denissen et al., 2018; Guseva, Dombrovskis, & Capulis, 2014). Personality traits in combination with job requirements predict important life outcomes (Judge & Zapata, 2015). To improve job satisfaction of employees and managers and minimise their work-related stress, there is an approach which involves authentic leadership and psychological capital (Dombrovskis, Guseva, & Capulis, 2017; Sultana, Darun, Yao, & Andalib, 2019).

Whereas U.Orth and R.Robins (2014) state that such personality trait as self-esteem can prospectively predict success in such domains of life as health and relationships, as well as success at work.

We believe that determining the lifestyle and self-esteem of managers can help to understand a person’s individual traits, principles of organising cooperation with colleagues, provide an opportunity to determine what ways and approaches employees can use in solving professional and life problems.

Problem Statement

Self-esteem and life-style features mediate the understanding of the individual perception of challenges by financial institution managers and have an important role in solving cooperation problem situations and making decisions. The employer can use their knowledge about employees’ lifestyle and level of self-esteem to analyse confrontations that may arise between company employees, which provides an opportunity to harmonise relationships. Having this resource of an individual’s internal plan at their disposal, the employer can build a company development strategy where employees demonstrate loyalty and are ready to achieve company aims.

Research Questions

Is there a correlation between a particular lifestyle and self-esteem level for financial institution managers in east Latvia and how does it affect their professional growth and quality of life?

Purpose of the Study

Study self-esteem and lifestyle as prognostic factors for the professional growth of east Latvian financial institution managers.

Research Methods

Budassi (2007) test “Quantitative Expression of Self-esteem” and Kern “Lifestyle Scale” (KLS) (Kern & Cummins, 1996; Kerns & Kummins, 2000) were used in the study.

S.A. Budassi test “Quantitative Expression of Self-esteem”

A participant is offered a list of 48 personality traits, from which they have to choose 20 that in their opinion describe the perfect personality “my ideal”. Of course, negative traits can also be present.

From the 20 personality traits selected, the participant creates a set of ideals d1 in the research protocol, beginning with the most important positive personality traits, in their opinion, and finishing with the least desirable, i.e. negative ones (1st rank — the most attractive trait, 2nd — a trait less attractive than the first one, and so on until the 20th rank).

Using the previously selected personality traits, the participant creates a subjective set d2, which includes 20 traits sorted in the descending order of their expression in their own personality (1st rank — the most characteristic trait, 2nd — a less characteristic trait than the first one, etc.). The result is recorded in the research protocol.

The aim of the result processing is to determine the correlation between personality trait ranks included in the percepts “Ideal self” and “Real self”. The correlation strength is determined using the rank correlation coefficient. The coefficient is calculated by first finding the rank difference

Interpretation of self-esteem:

r approaching +1 means high self-esteem;

r approaching –1 means low self-esteem;

r value –0.5 < r< +0.5 means adequate self-esteem.

Kern “Lifestyle Scale” (KLS)

The KLS was used in the Latvian adaptation (Kerns & Kummins, 2000). The test has a 35-item self-scoring assessment to “measure” lifestyle. The test consists of 5 scales: Control, Perfection, Need to please, Self-esteem, and Expectations.

5.3. Participants

The participants of the study were 23 financial institution managers in east Latvia aged 25 to 33.

Findings

Let us review the respondents’ self-esteem and lifestyle scale test results.

Result analysis according to Budassi test “Quantitative Expression of Self-esteem”

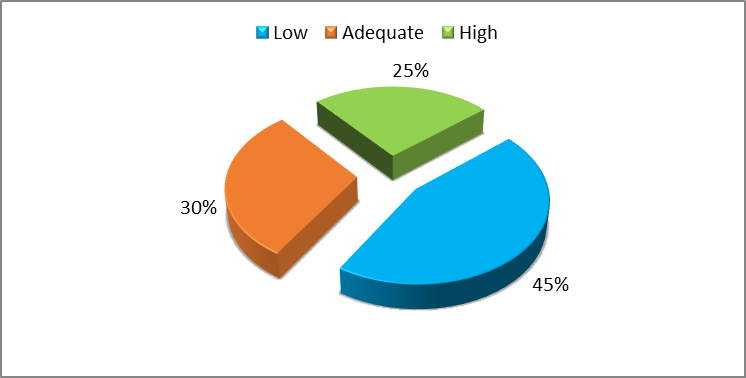

Distribution of self-esteem levels of financial institution managers is shown in Figure

As can be seen from the figure, low self-esteem is characteristic of the majority of participants – 45%. A relatively small proportion have high self-esteem – 25%, and 30% of respondents demonstrate adequate self-esteem. Thus we can state that two levels of self-esteem prevail in the group.

People with low self-esteem often still lack stable beliefs, and in different situations they go by the opinions and beliefs of others. A person with low self-esteem lacks confidence in themselves, often does not believe in their abilities, which is related to a negative evaluation of oneself. Thus initiative and activity level decreases; the person is unable to improve their quality of life and become aware of their value; in life and work they choose aims that are easy to achieve.

In case of low self-esteem, an employee at the beginning of their career typically experiences the feeling of anxiety, fear of negative evaluation, increased sensitivity and tendency to narrow down their communication circle.

Respondents with low self-esteem do not hope for success or good attitude to themselves, whereas real success is erroneously perceived as a chance occurrence.

Low level of self-esteem means dissatisfaction with one’s social status or social adaptation problems, or lack of support from others.

Adequate self-esteem was found in 30% of respondents. The respondents are aware of their strengths and weaknesses, even though they experience difficulty in communication with others. Their social adaptation process is gradual; they have a tendency for self-exploration, want to perceive themselves holistically, to avoid conflict between the internal and external level of pretensions.

High self-esteem was found in 25% of respondents. This situation can be considered inadequate because a person can have a feeling of inferiority in their professional field. People with inadequately high self-esteem are self-confident, cannot understand their negative action or activity, believe that they react “correctly” to their environment. If success is low in the activity process, they do not take it seriously, demonstrate expressed bragging and shameless behaviour. They can change jobs frequently because they feel unappreciated by others.

Result analysis according to Kern Lifestyle Scale

The respondents, when answering test questions, could choose one of 5 options, which determined the number of points on each scale.

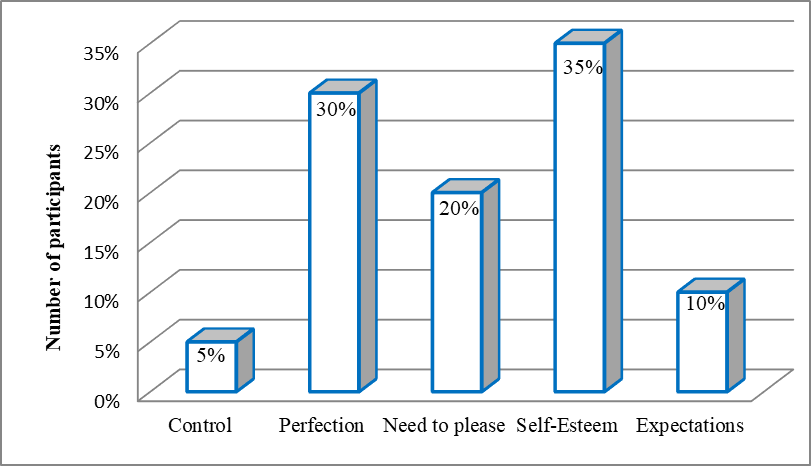

Description of the respondents’ lifestyle analysis results. The results are shown in Figure

As can be seen in the figure, the largest number of responses among the participants is found on the Self-esteem scale (according to lifestyle: Victim 35%) – these people have a tendency to criticise themselves and take things personally; they can also have low self-esteem.

They can pay attention to communicative interactions or information that confirms their feelings of inferiority. However, they can be deeply aware of others’ feelings. Management could have both physical and psychological difficulties because they take the energy they need from the surrounding social environment. With group members they can have difficulty clearly perceiving the true meaning of the group communication as well as the communicational needs of the group members. This is why there is a lack of organisational skill in solving strategic problems.

Overall, people with a high result on the self-esteem scale have effective communication. Still, when solving a problem, it can seem that they have low self-esteem and high emotional tension concerning the advancement of their career.

The second dominating lifestyle is Perfectionist (30%) on the Perfection scale. These are conscientious, careful and sensitive people; they are pedantic and follow all the rules; they do not like to make mistakes. They are best at performing individual tasks.

In relationships with others, representatives of this type feel more comfortable in situations where communication is direct and the rules are clear. As managers, they show more understanding towards others than towards themselves. In a group environment, there is better learning and desire to use working hours as effectively as possible for the performance of a task. Attention needs to be given to the use of clear communication, whereas lack of clear information about the rules and expected results may lead to functional difficulties within the workgroup.

Overall, the result on the Perfection scale shows that they are careful and specific in formulating tasks, demanding and diligent.

The third dominating lifestyle scale is Satisfaction. These are people who can be grouped into the category “A person who wants to please” (20%). Pleasing is manifested in two ways – it can be active or passive. The representatives of this scale seek validation from others, follow instructions, are diplomatic in relationships, mediators, good at avoiding conflict situations, but can often be in conflict with themselves. It can be difficult for them to be purposeful. The representatives of the Satisfaction style have a high socialisation level: they are friendly, social, sincere, reliable and sympathetic.

Since the respondents often have to work in groups, they express sensitivity towards others and avoid conflicts with colleagues. The can be excellent listeners but can experience difficulties if there is no opportunity to satisfy their own needs among colleagues. For the representatives of this type it is important to receive validation from others; however, they are unable to take necessary decisions due to some disappointment. It needs to be taken into account that they could work better with colleagues who need minimum management at work.

The Martyr lifestyle belongs to the Expectations lifestyle scale (10%). Representatives of this style often feel unwarranted dissatisfaction; they typically have a set of unmet expectations. They typically feel like a “second child” in the family because they always try to “outperform” the elder sibling. Basically, this lifestyle type tries to compete with others; however, they may be unaware of it. If dissatisfaction and unrealistic expectations are not properly controlled, the representatives of this type can demonstrate a very critical attitude to themselves and others.

Since the respondents were up to 33 years old, the Martyr may be able to compete on the job market and in a workgroup because professional growth is important at this age. The Martyr has a tendency to show-off in a team.

It can be stated that the representatives with this lifestyle with a high result on the Expectations scale can often find themselves in confrontation with colleagues because in situations of dissatisfaction they can project pressure. The need to control their dissatisfaction has a negative effect on working capacity and the needs of the organisation. The Martyr as a group manager is able to purposefully organise the working routine of the team, and as a group member as well, if their expectations are met; they can be a productive professional member of a team. Still, as group members, the representatives of this style tend to be pessimistic, critical to themselves and others.

The Control scale is less represented among the respondents. The Controller is confronting, tries to manage others, controls their emotions, fights for their truth, has a high productivity potential but no clarity about their capabilities. One of the positive features is the ability to manage, organise and implement the tasks set.

Whereas working with such people can involve difficulty having a say due to their demonstrative nature and petty quarrels.

Most important statistical processing results of self-esteem and lifestyle data

The data obtained were subjected to statistical processing using SPPS 21.0 software. The results are shown in Table

Table

Table

Table

Conclusion

A correlation tendency has been proven between a particular lifestyle and self-esteem in east Latvian financial institution managers:

•The lifestyle scale results show that for 35% of respondents the prevailing lifestyle is the Victim. The second prevailing style is Perfectionist (30%).

•Low self-esteem is characteristic of 45% of respondents. The person lacks confidence in themselves, often does not believe in their abilities, evaluates themselves negatively, is inactive and lacks initiative.

•For 30% of respondents, high self-esteem was found. The person has an expressly exalted attitude and the feeling of dissatisfaction from cooperation with others.

•A statistically significant correlation was found between low self-esteem and the Victim lifestyle. These people tend to be self-critical, have a subjective approach to solving problem situations, do not believe in their abilities and are not disposed to professional growth.

•A statistically significant correlation exists between high self-esteem and the Perfectionist lifestyle. The person can find themselves in confrontation with colleagues; they tend to be critical to others. Criticism and self-confidence impede social adaptation and professional growth. The activity process does not meet the status needs of the professional.

References

- Alavi, S., & Toozandehjani, H. (2017). The relationship between learning styles and students’ identity styles. Open Journal of Psychiatry, 7(2), 90-102.

- Budassi, S. A. (2007). Test “Nahozhdenie kolichestvennogo vyrazhenia urovnya samootsenki“ (test “Quantitative expression of self-esteem”). In L.D. Stolyarenko (Ed.), Osnovy psichologii/praktikum (Basics of psychology/praxes), pp.479-480. Rostov-on-Don: “Phoenix”.

- Chang, W.-H., Hsiao, H.-J., & Chen, I.-J. (2019). Learning style preferences of EFL College students and their causes. Open Journal of Modern Linguistics, 9(2), 59-66.

- Denissen, J. J. A., Bleidorn, W., Hennecke, M., Luhmann, M., Orth, U., Specht, J., … & Zimmermann, J. (2018). Uncovering the power of personality to shape income. Psychological Science, 29(1), 3-13.

- Dombrovskis, V., Guseva, S., & Capulis, S. (2017). General and professional stress of mobile and operational staff of private security companies. SGEM2017 Conference Proceedings “Science & Society”: 4th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Social Sciences and Arts SGEM 2017, 24-30 August, 2017, book 3, Vol. 2, pp.153-160.

- Fan, J. L., & Smith, A. P. (2017). Positive well-being and work-life balance among UK railway staff. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 5(6), 1-6.

- Fan, J. L., & Smith, A. P. (2018). The mediating effect of fatigue on work-life balance and positive well-being in railway staff. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 6(6), 1-10.

- González-Celis, A. L., Chávez-Becerra, M., Maldonado-Saucedo, M., Vidaña-Gaytán, M. E., & Magallanes-Rodríguez, A. G. (2016). Purpose in life and personal growth: Predictors of quality of life in Mexican elders. Psychology, 7(5), 714-720. DOI:

- Guseva, S., Dombrovskis, V., & Capulis, S. (2014). Personality Type and Peculiarities of Teacher's Professional Motivation in the Context of Sustainable Education. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 112, 133-140. DOI:

- Judge, T. A., & Zapata, C. P. (2015). The person–situation debate revisited: Effect of situation strength and trait activation on the validity of the Big Five personality traits in predicting job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 58(4), 1149–1179. DOI:

- Kern, R. M., & Cummins, C. C. (1996). Kern Life Style Scale interpretation manual. Bangalore, India: CMTI Press.

- Kerns, R. M., & Kummins, Č. K. (2000). Kerna dzīves skalas interpretācijas rokasgrāmata. Rīga: Rīgas pilsētas Skolu valdes Skolu psiholoģiskās palīdzības centrs.

- Orth, U., & Robins, R. W. (2014). The development of self-esteem. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(5), 381-387.

- Shagvaliyeva, S., & Yazdanifard, R. (2014). Impact of flexible working hours on work-life balance. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 4(1), 20-23. DOI:

- Shamionov, R. M., Grigoryeva, M. V., & Usova, N. V. (2013). The Subjective Well-being of Russian Migrants in Spain and of Foreigners in Russia. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 86, 498-504.

- Sultana, U. S., Darun, M. R., Yao, L., & Andalib, T. W. (2019). Enhancing authentic leadership, psycap, job stress and job satisfaction: Innovation combined effect. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences, LXV, 80-88.

- Vallejo Martin, M., & Moreno-Jimenez, M. P. (2012). An evaluation of life satisfaction within migratory experience according to psychological variables. Psychology, 3(12a), 1248-1253. DOI:

- Wong, F. M. F. (2019). Life satisfaction and quality of life enjoyment among retired people aged 65 or older. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 7(5), 119-127.

- Zhang, M., Quan, Y., Huang, L., & Kuo, Y. L. (2017). The impact of learning styles on academic achievement. International Journal of Intelligent Technologies and Applied Statistics, 10(3), 173-185. ttps://doi.org/ 10.6148/IJITAS.2017.1003.04

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

12 December 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-073-0

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

74

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-419

Subjects

Society, culture, education

Cite this article as:

Guseva, S., Dombrovskis, V., Capulis, S., & Korniseva, A. (2019). Self-esteem and Lifestyle of Financial Institution Managers in East Latvia. In S. Ivanova, & I. Elkina (Eds.), Cognitive - Social, and Behavioural Sciences - icCSBs 2019, vol 74. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 312-320). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.12.02.37