Abstract

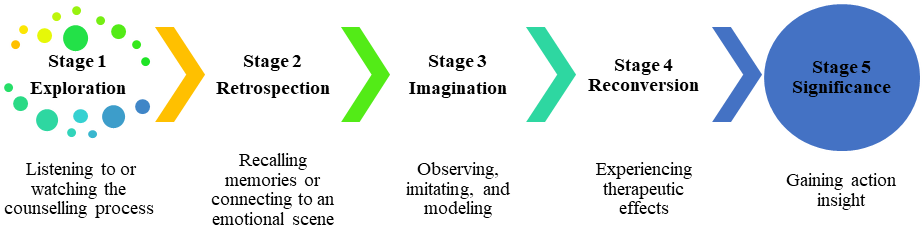

Everyone encounters challenges and hardships. Some problems are easily handled, while others may never be resolved, causing serious issues later in life. Therapeutic healing in psychology refers to achieving relief or cure through specific psychological processes. Some therapies used to deal with unresolved issues and managing setbacks centre around experience-sharing in group settings. Therapeutic healing does not happen randomly. There are recognizable stages in the process of integrating experiences and gaining insights from group therapy. This study explored the stages in the therapeutic process of the mirror effect as experienced by students who observed group therapy in a group counselling class. Thirty registered social workers, each of whom had taken the counselling course, voluntarily participated in a semi-structured interview. Thematic analysis was used to identify and analyse themes within the qualitative data. Results showed that students who observed group therapy experienced the therapeutic impacts of the mirror effect, helping them understand how the effect works. Students reported undergoing five-stages in the process: exploration, retrospection, imagination, reconversion, and significance. The research confirmed that mirror effects take place during counselling education, and students may experience self-healing through the witnessing of the counselling process, giving them direct experience with a technique they can use for others. The implications are that observers of group therapy experience mutuality in the healing experience. This phenomenon has never been thoroughly examined, and our work suggests future studies involving student observers may provide insights into healing processes and benefits of experience-based education for counsellors.

Keywords: Group counsellingmirror effecthealing processexperiential learningeducationqualitative study

Introduction

Group counselling differs from passive talking in that each person can observe the interactions among members. Verbal and non-verbal expressions between people, counselling skills, the changes, and the consequences, as well as the reflection on those dynamics, make the group counselling process more meaningful, memorable, and motivating. This action-centred approach has proven especially successful for engaging students (Jaison, 2018). When students are involved in empathic and action understanding while merely listening to or watching a counselling process, such as in familiar situations, in which matching between observation and learned knowledge is automatically executed (Ho, 2019a), this phenomenon is defined as a mirror effect. Employing the mirror effect in a group setting uses action to heal people (Jacobs, Schimmel, Masson, & Harvill, 2016). Members of the group share in each other’s emotional experiences. It is similar to observational learning, modelling, or vicarious learning (Bandura, 2017; Jacobs et al., 2016). However, with group counselling, the learned behaviours are more advanced and are accompanied by a deep thought process.

Based on an action-oriented and experiential modality, some students portray the therapist and client, and other members demonstrate the client’s story during the therapeutic activity in a course of group counselling (Corey, 2016). Students do not talk about the client’s problems; they act them out. Students are provided with an opportunity to demonstrate their skills in action and achieve experiential satisfaction, transforming intellectual knowledge into overt behaviour.

Through experiential learning, students acquire not only cognitive explanations, but direct experiences, enabling them to access a myriad of thoughts and feelings (Chen & Rybak, 2018). A student’s internal experience is externalized and experienced from a new perspective. As a result, ‘the impact on a client’s life of overwhelming responsibilities is immeasurably more powerful experienced in a visual and physical way than it is merely discussed verbally and known cognitively’ (Zimberoff & Hartman, 1999, p. 78, para. 3). This phenomenon is called ‘action insight’, which is comparatively more powerful and enduring than verbal insight (Corey, 2016). Along with the students, the teacher and other participants benefit from the effects of group counselling.

Mirror effects occur as people develop an action insight from witnessing the process of group counselling (Ho, 2019a). This study aims to investigate the psychological process in the generation of the mirror effect by examining how it occurs in the experiential teaching method in group counselling education.

Mirroring as a Counselling Technique

J. L. Moreno was among the first to recognize the healing power of a group through observing group interactions and relationships (Baim, 2017), and pioneered psychodrama and the techniques of mirroring in group therapy. In this technique, members in the counselling group assist in handling a client’s situational problem. They may be coached by the therapist or use their own experiences in helping the client. Anybody can participate in mirroring, including the therapist, group members, or the audience (i.e. an observer who is merely observing the counselling process). Clients watch the counselling process as if they are viewing themselves in a psychological mirror (Moreno, 1946, 1977).

The client is portrayed by someone who imitates him/her verbally and nonverbally, and this auxiliary member, is the group member who is ‘playing’ or acting out the role of other significant people experiencing the client’s story as if it happened to them. They may advise the client how and why to express him/herself and behave in this way. The auxiliary member mirrors what the client is doing, using verbal and non-verbal language (e.g. posture and voice tone) and action (Telias, 2019). The client finds him/herself empathizing with a particular character when watching a dramatic enactment (Lanzoni, 2018). While mirroring the action, the auxiliary member’s body language can create certain bonds or connections with the client, thereby assisting with the establishment of rapport (Kuhnke, 2016). He/she will then realize that he/she are portrayed in the scene, and identify with the character. Each member becomes the healing agent for the others.

Mirror Mechanisms in Group Counselling

In mirroring, the clients can observe, imitate, and model the responses of others. The group members, observers, or even the therapist may retrieve memories and recognize similarities to their own lives in the situation. Everyone in the counselling sessions may experience healing along with the clients (Fung & Zhu, 2018). All present in the counselling room can verbalize their inner feelings and experiences through the mechanism of mirroring, consequently creating the mirror effect.

Observation

Mirroring creates a setting whereby members in a group can place themselves in a separate space to observe others’ speech and actions as if it were them. This psychological distance allows people to develop a more realistic appraisal of their own selves (McDonald, Chai, & Newell, 2015). This way the client can view their own beauty, charm, flaws, awkwardness, and clumsiness, and perceive how others see them, maybe seeing the gap between what they are and what they want to express. Having another point of view with which to interpret and recognize the behaviour as being his/her own, the client develops a new reflection on his/her behaviour (Clarke, Binkley, & Andrews, 2017).

Imitation

Mirroring is facilitated by our innate ability to imitate. We can observe and replicate others’ behaviours. It can take the form of an imagined scene in one’s minds (Modell, 2006) as when reading a novel. Further, it can be an unconscious process, generating fantasies as vivid as the reality. Imitation can be performed mentally. Because of deferred imitation, humans can replicate any actions later to deal with problematic situations (Gilmore & Meersand, 2015).

Modelling

Humans can replicate any of their own actions, actions of others that they have observed, or actions that they have imagined. In more advanced situations, individuals recognize their limitations and learn from someone more knowledgeable and experienced who demonstrates new behaviours in ‘‘a continuous and reciprocal interplay between cognition, behaviour, and the environment’’ (Merrotsy, 2017, p.96, para. 2). By modelling, they may also develop new critical thinking skills to employ in the future (Merrotsy, 2017).

Action Insight

Action insight integrates emotional, cognitive, imaginary, behavioural, and interpersonal learning experiences into various kinds of action learning by communicating with action-language (Kellermann, 1992). Action insight cannot be attained through introspective analysis, only via action. It may come as a sudden flash or as a gradual discovery. The ‘in-sight’ refers to the process of looking ‘in’, ‘the searching for inner truth and awareness of self, in contrast to grasping the outer world of the senses, the so called reality’ (Kellermann, 1992, p. 87, para. 2). This protective environment of group therapy allows clients to freely express their feelings, thoughts, emotions, and words through action.

The therapeutic process transfers ‘talking’ into ‘action’, providing an opportunity ‘to heal the past, clarify the present, and imagine the future’ (Chimera, 2015). Action insight develops largely as a result of three types of learning: 1) experiential learning; 2) learning through doing; and 3) non-cognitive learning (Kellermann, 1992, p. 90, para. 4). In a dramatic situation, a person is given the opportunity to creatively re-enact specific experiences to try to obtain an answer to uncertainties in their life with the assistance of concrete therapeutic processes. The person acts out him/herself to gain insight through action.

Created knowledge acts to cognitively coordinate a participant’s behaviour in relation to how their experiences from the past match with the present reality. This kind of cognitive and reflective knowledge can be implemented to assist people in resolving life situations or enable them to gain insight.

Generation of Mirror Effect

The inner life of the students and observers is widely stimulated by the process of witnessing counselling. The adaption of an action-oriented and experiential approach in learning and teaching, across the whole curriculum in group counselling education, allows students to cultivate analytical, critical, and scientific attitudes and to nurture professional counselling skills in a holistic, experiential learning environment.

Because of the ripple effect, some participants will be influenced by the process. For some, a degree of positive or negative change will occur unconsciously as they begin to experience mirror effects. Mirror effects have three defined sub-types which, looked at together, is a psychological process in itself that has been generated from mirroring (Ho, 2019b). These sub-type effects are:

Problem Statement

This study examined a group counselling course. To enhance the capability of the therapists, experiential learning has been adopted as an approach to teach the course. The atmosphere and ambience construct a psychological mirror for students who, while witnessing the counselling process, can see themselves in the ‘mirror’ and experience the therapeutic effect of the counselling. Students may then develop empathic understanding toward the characters in the scene. The healing process of the observed counselling may trigger emotions and some of the students may recall emotional memories connected to an associated event.

In a group counselling session, the client is placed in a safe experimental situation (Lefebvre, Sears, & Ossege, 2019), but mirroring has a significant effect on the audience too. The actions of the client, the group members, and the counsellor appear to create a psychological mirror, similar to the mirroring technique being done for the clients benefit, whereby students participating in the class simply as witnesses of the process of counselling will generate a mirror effect. However, the literature on the subject of group counselling and education has rarely mentioned the mirror effect in regard the observers, making it difficult to examine or prove through review of the texts.

Most studies have consisted of the commentaries of counsellors based on the clients’ experiences with the therapy (e.g. Kim, 2003), and very few studies have examined the counsellor, group members, or audiences directly. Therefore, it has not been shown how the therapeutic effects of the group counselling process affect each person in the group.

Research Questions

Against this background, this study was conducted in a university that provides group counselling education using experiential learning as a method of instruction. The study proposed to answer the following questions:

3.1.How do mirror effects take place in experiential group counselling education?

3.2.In what ways does the mirror effect influence the psychological process and generate healing effects?

Research Methods

The qualitative analysis blends empirical data and abstract concepts into the form of words, offering an in-depth understanding of group counselling education, and to explore the psychological process of the mirror effect.

Sample

The participants were part-time students registered in the Bachelor of Arts in Social Work Program. Thirty students were successfully invited from the group counselling course using experiential learning. All invitees were registered social workers who were working at the social service centre or had previously been employed at the social service centre. Table

Teaching Techniques

The course developer’s primary objective is to facilitate the professional growth of students through the use of action in the learning and teaching of counselling, therefore deliberately keeping the lectures short and promoting experiential learning. Table

Procedure

An ethical review was approved by the College Research Ethics Sub-Committee at the University before commencing this research. All students were invited via in-class promotion from the group counselling course. Subsequently, students signed up and returned a consent form with personal contact information to indicate their interest and agreement to participate in the interview. Invitees were asked to review and agree to a declaration proclaiming that participation in this research would not and will not affect their academic results and would have no consequences. All students participated voluntarily in an individual semi-structured interview immediately after completing the course. Student identities were kept confidential by assigning a number to each interview and tape recording.

Data Analysis

This study adopted an interpretivist perspective and thematic analyses was carried out for each respondent. The researcher and the research assistants checked the accuracy of the students’ views, read and re-read the transcripts, and noted down initial ideas about mirror effects. Considering inter-rater reliability, the research team first engaged in coding the transcripts independently and then met to discuss group coding, to engage in constant comparisons of commonalities and divergences in themes, which served to uncover the theory. This is a triangulation process, which produces convergence and, consequently, supports validity.

The data were identified by ‘theme’, ‘pattern’, and ‘category’. In general, themes are related to central meanings that organize student’s experiences and which are identified in repeated ideas, sentences, and words that students use to describe their experiences. A thematic map of the mirror effects was then generated. To refine the specifics of each theme, it was necessary to engage in an analysis of the overall process and experiences of mirror effects and the experiential learning approach, and then to generate clear definitions and names for each theme inductively. Further analysis recorded the frequencies across responses.

To increase the internal validity, the related data were extracted, a final analysis undertaken, and findings related back to the research questions and literature. After discussion, and with the consensus of the researcher and the raters, the final report was written and reviewed by all the team members. The patterns and themes were verified again until a final consensus was reached. The refined report only showed the consolidated result, without any information that could identify any person individually. To protect and maximize the benefit to the students, the data were kept confidential and were not disclosed to any of the teaching staff. Table

Findings

The therapeutic mirror technique allows the client to reflect upon his/her overwhelming and too-familiar actions by observing a scene from a critical distance (Casson, 2014). This physical detachment provides the clients with an increased sense of control over their actions. At that moment, the client may emotionally detach from the situation. The episode may allow students who are witnessing the counselling process to recall their own emotional memories connected to the incident, enabling them to imitate others’ actions through observation, imitation, and modelling. Figure

Stage 1: Exploration

The first stage, exploration, consists of exploring a familiar or unfamiliar episode, gathering information, and embarking upon initial conscious work on the situation. Students might collect information from multiple levels and various forms of stimuli.

Exploration sometimes includes participation in or through the situation to help students learn about or familiarize themselves with it. As Student 01 stated,

In some cases, they are related to my daily life. There are sections which make me uncomfortable, or which remind me of some of the unhappy pictures in life, but these are not frequent. … I am not very excited, or impulsive, or feeling hurt. I just slightly remember this, then it is done. (Student 05)

If the clients’ stories allow the students to think about similar past experiences, those students tend to bond closely with the stories.

Students were not influenced by every case. Some cases were more closely related to their own situation and would have greater power over them than others.

The video recordings illustrated the problems faced by the clients and this is/was quite similar to what I encountered now, or in the past; for example, family problems, work frustrations... These were quite related to my problems, or some psychological emotional problems, or troubles. (Student 30)

Students were merely listening or watching a person (i.e. the client) but they experienced the counselling session as a mirror of themselves. It seemed to the students that they were looking at their own image in a mirror. Each student witnessed the counselling process as their subjective, observing self.

Stage 2: Retrospection

The second stage may involve active cognitive processing, the automatic spreading of memory retrieval, the passive forgetting of superficial details of previous attempts at the situation, increasing emotional awareness, or empathic understanding.

For students who had analogous experiences with the client, memories of the episode were evoked. Students with no such experiences might develop empathic understanding. Past experience may imprint in our mind, either consciously or unconsciously, and these are the fragments of our memory. Despite this, each incident in our memory has its particular content, time, space, and character, which act to organize the structure of our lives and influence future experience. Human thoughts, feelings, and emotions are all tied together and influenced by physical sensations and memories (TenDam, 2014).

Students who had experienced and remembered analogous incidents could feel and touch the client’s heart.

While the client was sharing his/her experiences and feelings, I was reminded of my own memories and emotions. Although I do not share the same experiences and have not had the same encounters as the client, I could share the same feeling and could feel exactly what he/she feels. (Student 18)

The retrieval of historical memories triggered students’ feelings and emotions.

I can listen to the client sobbing or crying, and when his/her stories are similar to my experiences, it touches my heart deep and I feel indebted as if I were the client. Though we do not have the same experiences, whenever I hear a sentence, whether I had thought of it before or if it is very similar to my thoughts, I have a very special feeling. (Student 02)

The counselling process was not only associated with individuated life events, but also with some of the social workers ‘clients or others’ stories.

Sometimes I do think of the clients that I have encountered before, or of stories I have heard in church, and all of these recalled my past experiences and situations of being a counsellor. (Student 25)

Some scenarios were quite similar to those experienced by colleagues or by me and even the background was very similar to that of the service users. (Student 11)

Students conjured up memories. As a result of empathy, the aroused feelings and emotions generated thoughts associated with client stories. The students were able to develop ‘tele’ (i.e. two-way empathy) with the client (Gehart, 2016).

To understand how humans are able to empathize with each other’s experiences, the concept of intersubjectivity, which is defined as ‘the sharing of subjective states by two or more individuals’, is often used (Scheff, Bernard, & Kincaid, 2016, p. 41, para. 2).

Stage 3: Imagination

The third stage involves observation, stimulation, imagination, and role repertoire. Whilst a person was speaking and/or enacting scenes in the audio or video case recording, he/she was a role model for other people. Roles, in turn, imply the use of a script, which is a sequence of actions that define those roles (Erskine & Moursund, 2018). A script is a story that is intended to achieve some form of narrative sense, and therefore it is necessary that the story occurs in a certain sequence. Each person is a role player (Honderich & Heyward, 2019). Generally, ‘the greater the number of roles in our repertoire, the better able we are to meet our needs and function successfully, as long as we are able to utilize the roles effectively’ (Baim, Brookes, & Mountfors, 2002, p. 20, para. 2).

Through watching and listening to the case recordings, students might split into different ‘selves’ and exercise another role. Also, they might dissociate themselves ‘from their feelings when need be and go into a visual mode’ (Nicholas, 1984, p. 20, para.4) and ‘come in split off from their feelings and … seeing pictures in their head’ (Nicholas, 1984, p. 21, para.1). They might imagine that they are one of the characters, such as clients, counsellors, group members, or an audience member (i.e. the role of student, observer, or assessor), who presented in the counselling group. In this world of imagery, students might imitate, visualize or mentally ‘try out’ the character’s speech and behaviours, or act out different attitudes and complexities that they are unable to present in the real world, such as fears, regrets, or yearnings.

If the scenes were similar to students’ experiences, students might glimpse themselves in others’ stories. Students might try to feel and take on the role of the client.

The scene allows me to fall into the client's scenario. It seems I have taken up the client's role too. These things do touch me; some of the things did happen in my work life and they also touched me. (Student 29)

Students felt as if the clients were being counselled by the professor.

Blatner (1985) pointed out that, during ventilation, people can expand the concept of ‘self’ and explore viewpoints and feelings they had previously buried and disowned.

At that time, they were connecting with the professor and demonstrating their professional roles mentally. Students were undertaking counselling together with the professor.

Inside the classroom, I should be an observer... I would say I am even the professor’s companion. We are doing counselling together. (Student 25)

This mental process generates an interpersonal competence, which enhances students’ knowledge of how to solve daily life problems. Those experiences facilitate students becoming an effective helping professional.

Members in a group educate each other, and group members touch each other literally and emotionally (Forsyth, 2019). To a certain extent, the students, as group members, made efforts and contributions to the group.

When I was listening to the audio recordings, … I was devoted, imagining I was the group member, listening with the group members to what the professor was saying. When the group members were doing some sharing among ourselves, I would relate myself to it and try to feel their emotions. Both I, and the members, felt relieved. (Student 17)

This atmosphere dispersed into every corner of the classroom. Students learned not only to perform a group member role, but also to actively participate in a group to support others.

With a psychological distance, students as an audience could step outside to perform their role of learners, observers, or assessors mentally. Student 25 stated, ‘

Stage 4: Reconversion

The fourth stage is important for achieving a therapeutic effect when the client’s healing experience is imbibed by the students introspectively. Looking at the psychological mirror, students can see their shadow or other people struggling in similar circumstances, to express their blocked thoughts when their suffering is voiced by others or to teach a new coping strategy. In addition, it aided the achievement of emotional expressiveness, interpersonal competencies, and professional counselling skills.

The episodes of the clients’ stories aroused very meaningful conscious experiences, such as thinking, wishing, and hoping.

Within the process, I could feel that the client was in pain. When it came to the end of the counselling session, the client revealed the effects of the treatment by the professor; the treatment was positive and constructive, and I felt liberated. … if I were the client, it was a difficult decision. (Student 07)

The successful experiences of the clients influenced the students’ experiences and their attitudes and judgments towards counselling.

Students might imagine that, had they received supportive feedback from people such as the professor, it would have resulted in their past experiences toward counselling being corrected.

Every time, the professor's intervention in helping the clients to solve their problems was very smooth and successful. At last, when the clients gave some feedback, they usually said ‘what the professor said gave me a deep feeling’. This does not only apply to the clients; it applies to me too. There was also positive encouragement towards the clients, once feedback was heard. In some scenarios, there were similarities between myself and the clients; when the professor psychologically touched the clients' feelings, it also did the same to me. (Student 20)

Students might be positively inspired through realizing that other people’s problems have been solved through a release of emotions, by learning new skills and trying new approaches to life situations that could be much more effective.

Stage 5: Significance

The fifth stage involves gathering conscious experience that is given significance through one’s own interpretation, so as to understand why the particular things that happened in this course may have effects beyond the classroom and which may be adapted in relation to other life events. By discovering, evaluating, planning, organizing, implementing, and refining, students might fully experience action insight in order to achieve a positive mirror effect.

Student 15 used some of the learned skills in his/work workplace. His/her counselling skills were enhanced.

I focused more on cognitive thinking when I spent time with teenagers in the past. If I was asked about the teenager's feelings, I was not very good at them, and would even try to escape. …If I were involved, I would just do it at a superficial level and not drill too deep. At work, I once encountered a person who was very emotionally unstable. I tried to use the FBI [Feeling, Best, and Insight] skill that I saw from the professor, but I did not know much about how it worked. When I observed his responses, it seemed the skill adopted was all right but still I did not know what I needed to do further… Now, I have learned it and I am more confident in using the FBI skill learned in lessons. (Student 15)

Student 25 gained more confidence in applying counselling skills.

In the past, I did not have much confidence and doubted whether I was doing the right things… I used to have an inflexible target in providing therapy but now it seems I am able to manipulate it. I can develop tele with my clients. Put it this way, I have more flexibility now… When I adjust my mindset or make any decisions, I am clearer on how to do it. (Student 25)

Students discovered ways of implementing the counselling skills. By visualizing and interpreting a person’s action in a counselling process, students gained meaningful experience which will shed new light on how to gain control over their own lives. Finally, the students gained action insight and achieved positive mirror effect.

Conclusion

The results of this study support the use of experiential learning while also confirming that the experiential method of teaching group therapy techniques has some healing influence on the positive mirror effect (Ho, 2019a). The experiences described by the student observers verifies the effectiveness of group therapy in helping people understand their own patterns of behaviour and gain insights as to why people say they behave as they do and what their behaviour means to them. This study explored the process involved in the therapeutic healing of mirror effects from the perspective of those who experienced that process. The theoretical justification for mirror effects through action insight is grounded in group counselling (Bakalım & Karçkay, 2017), whereas the theoretical justification for the application of action and experiential learning in the context of counselling education is based on adopting the philosophy, concept, and skills of group counselling therapies. This very combination can make theory building endlessly fascinating.

The results also validated the use of students as study candidates in this context. Students participate as witnesses, and so are not intentionally chosen as one of the target clients. Thus, there is no limitation placed on the number of people who can participate in counselling education. In the process, it is not necessary for students to disclose their own stories or relinquish any privacy. Hence, students who participate in the group may be influenced by the mirror effects. Some students may be treated automatically through witnessing a counselling process.

However, if students have analogous problems, their emotions are triggered but they gain neither treatment effects nor action-understanding; in such a case, they may need to seek follow up therapy after attending group counselling education. It is clear that the counsellor and other helpers must pay serious attention to caring for all participants, even passive participants

Mirroring may have delayed effects, which may be either general, positive, or negative (Ho, 2019a). To test the long-term efficacy of mirror effect therapy, researchers may consider a longitudinal design to run through the entire counselling course, including follow-up qualitative interviews and quantitative measurement questionnaires. This method can provide information to make comparisons between participants’ initial response at the beginning of the course and the experiences that they record after each lecture.

References

- Baim, C. (2017). Psychodrama. In C. Feltham, T. Hanley, L. A. Winter, The SAGE handbook of counselling and psychotherapy (4th ed.). (pp.285-290). Los Angeles, CA: SGAE.

- Baim, C., Brookes, S., & Mountfors, A. (Eds.) (2002). Geese theatre handbook: Drama with offenders and people at risk. England: Waterside Press.

- Bakalım, O., & Karçkay, A. T. (2017). Effect of group counseling on happiness, life satisfaction and positive-negative affect: A mixed method study. Journal of Human Sciences, 14(1), 624-632.

- Bandura, A. (Ed.) (2017). Psychological modeling: Conflicting theories. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Blatner, A. (1985). The dynamics of catharsis. Journal of Group Psychotherapy, Psychodrama & Sociometry, 37(4), 157-166.

- Casson, J. (2014). Scenes from a distance: Psychodrama and dramatherapy. In P. Holmes, M. Farrall & K. Kirk (Eds.), Empowering therapeutic practice: Integrating psychodrama into other therapies (pp.181-202). Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley.

- Chen, M. W., & Rybak, C. (2018). Group leadership skills: Interpersonal process in group counselling and therapy (2nd ed). Singapore: SAGE.

- Chimera, C. (2015). Emerging practices of action in systemic therapy: How and why family therapists use action methods in their work. (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Bedfordshire, UK. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10547/565810

- Clarke, P. B., Binkley, E. E., & Andrews, S. M. (2017). Actors in the classroom: The dramatic pedagogy model of counselor education. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 12(1), 129-145.

- Corey, G. (2016). Theory and practice of group counseling (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

- Erskine, R. G., & Moursund, J. P. (2018). Integrative psychotherapy in action. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Forsyth, D. (2019). Group Dynamics (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

- Fung, K., & Zhu, Z. H. (2018). Acceptance and commitment therapy and Asian thought. In R. Moodley, T. Lo & N. Zhu (Eds.), Asian healing traditions in counselling and psychotherapy (pp. 143-158). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Gehart, D. R. (2016). Theory and treatment planning in counseling and psychotherapy. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

- Gilmore, K. J., & Meersand, P. (2015). The little book of child and adolescent development. New York, NY: Oxford.

- Ho, W. Y. (2019a). Mirror effects: Curative factors of group counseling in tertiary education. International Journal of Research in Teaching, Learning, Creativity & Technology, 2(1), 95-120.

- Ho, W. Y. (2019b). Starting literature review in qualitative research: An illustration using the mirror effect. In K. K. Tsang, D. Liu, & Y. B. Hong (Eds.), Challenges and opportunities in qualitative research: Sharing young scholars’ experiences (pp.7-18). Singapore: Springer.

- Honderich, E. M., & Heyward, K. (2019). The counselor’s role in fostering emotional and cognitive development across the life span. In M. O. Adekson (Ed.), Handbook of counseling and counselor education (pp. 238-254). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Jacobs, E. E., Schimmel, C. J., Masson, R. L., & Harvill, R. L. (2016). Group counselling: Strategies and skills (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

- Jaison, J. (2018). Qualitative research and transformative results: A primer for students and mentors in theological education. India: SAIACS.

- Kellermann, P. F. (1992). Focus on psychodrama: The therapeutic aspects of psychodrama. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Kim, K. W. (2003). The effects of being the protagonist in psychodrama. Journal of Group Psychotherapy, Psychodrama & Sociometry, 55(4), 115-127.

- Kuhnke, E. (2016). Body language: Learn how to read others and communicate with confidence. UK: Wiley.

- Lanzoni, S. (2018). Empathy: A history. New Haven, London: Yale University Press.

- Lefebvre, A. D., Sears, R. W., & Ossege, J. M. (2019). Group therapy for voice hearers: Insights and perspectives. New York, NY: Routledge

- Lo, T. W. (2012). Teaching group counseling in Hong Kong: The experience of a Teaching Excellence Award winner. In B. C. Eng, (Ed.). A Chinese perspective on teaching and learning (pp.77-91). New York, NY: Routledge.

- McDonald, R. I., Chai, H. Y., & Newell, B. R. (2015). Personal experience and the ‘psychological distance’ of climate change: An integrative review. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 44, 109-118.

- Merrotsy, P. (2017). Pedagogy for creative problem solving. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Modell, A. H. (2006). Imagination and the meaningful brain. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Moreno, J. L. (1946, 1977). Psychodrama, First volume. Beacon, NY: Beacon House.

- Nicholas, M. W. (1984). Change in the context of group therapy. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel.

- Scheff, T. J., Bernard, P., & Kincaid, H. (2016). Goffman unbound!: A new paradigm for social science (The Sociological Imagination). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Telias, R. (2019). Moreno’s personality theory and its relationship to psychodrama: A philosophical, development and therapeutic perspective. New York, NY: Routledge.

- TenDam, H. (2014). Deep healing and transformation: A manual of transpersonal regression therapy. Netherlands: Tasso Publishing.

- Zimberoff, D., & Hartman, D. (1999). Heart-centered energetic psychodrama. Journal of Heart-Centered Therapies, 2(1), 77-98.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

07 November 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-071-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

72

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-794

Subjects

Psychology, educational psychology, counseling psychology

Cite this article as:

Ho, W. W. Y. (2019). Students’ Experiences Of The Mirror Effect While Studying Group Counselling. In P. Besedová, N. Heinrichová, & J. Ondráková (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2019: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 72. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 110-125). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.11.9