Approaching Limits Of Participation? Trends In Demand For Non-Formal Education In The Czech Republic

Abstract

The paper deals with the long-term participation of adults in non-formal education (NFE). It is based on the thesis that although the average participation in the NFE has increased in the past two decades, this has not taken place across the board. In countries where participation in the NFE reached 45-60% of adults as early as in year 2000, participation tends to stagnate or decline rather than continue to grow. Based on these findings, we believe that the development of adult participation in the NFE suggests that the saturation threshold has been reached. The aim of the study is to discuss whether, in the case of available empirical data on the participation of adults in NFE in the Czech Republic, a tendency towards the saturation threshold reaching can be observed. For this purpose, the paper uses secondary data from the CZ 2005 and AES 2007, 2011 and 2016 surveys. Based on a descriptive analysis of data in the form of time series, we have found that with the increase in NFE participation, the adult demand for further participation in education and training has substantially decreased. It has fallen significantly in those who have not previously had experience with NFE, and especially in those who had participated before. As a result, the saturation of adult participation in NFE has increased significantly and demand for it has decreased.

Keywords: Adult education and learninglifelong learningsaturation thresholdeducation inequalitysupply and demand for education

Introduction

Non-formal education (NFE) of adults has long been at the heart of the European Union's (EU) educational and social policy (CEC, 2012, 2014). At the same time, its importance and usefulness have been mentioned in several important strategic documents of non-governmental and non-profit organizations such as UNESCO (GRALE, 2013, 2016) and OECD (EDG, 2015). In this paper, the NFE is understood to be in line with these documents, i.e. any organized adult learning activity that takes place outside the formal education system and through which adults develop their competencies, with or without the certification of the outcomes the activities.

The importance of the NFE as a social practice rests, according to a number of authors (see e.g. Antikainen, 2006; Blossfeld, Kilpi-Jakonen, Vono de Vilhena, & Buchholz, 2014; Field, 2006; Psacharopoulos, 2006; Regmi, 2015) in contributing to increasing the competitiveness of economies both at macro-regional and national levels as well as at cities or companies at micro social levels. In addition, it has positive functions for many areas of non-economic life, such as higher levels of civic engagement (Biesta, 2011), better quality of life, higher levels of innovation (Desjardins, 2017) or adults' ability to make use of their unique potential to change their life situations (Sen, 1997).

For these reasons, one of the central goals of national and transnational policies is the systematic increase in adult participation (which is most often defined by belonging to the age group of 25-64 years) in the NFE. This goes hand in hand with reducing inequalities in access to it, especially for those social groups that may be the most disadvantaged in this regard – for example, women on maternity leave, the elderly, the unemployed or young adults (Boeren, 2016, 2017; Riddell, Markowitsh, & Weedon, 2012).

However, there are significant national differences in participation in the NFE, as shown in Table

Not only does the overall rate of adult participation in the NFE vary from country to country, but it also dynamically develops in some countries, regardless of the structural frameworks of the welfare state or labor market in which the NFE was originally formed (Verdier, 2017, 2018). Given the evolution of participation in the NFE, two major global trends were observed in the last two decades (Desjardins, 2015, 2017; Rubenson, 2018). First and foremost, the growth in the overall participation rate of adults involved in lifelong learning has accelerated significantly in the context of the 'knowledge society' emergence since the 1980s and 1990s. Secondly, there is an increase in the proportion of NFE participants who are educated primarily because of the use of newly acquired skills in their working life (job-oriented-training).

However, both of these trends have very divergent trajectories at the level of individual countries, as documented in Table

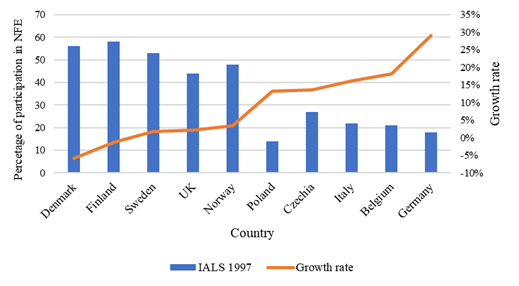

Based on data from these surveys, a pair of developmental patterns of adult participation in NFE can be identified:

The Early NFE Adopters pattern, which is typical of countries with a higher NFE participation rate (40-60%) already in the late 1990s and which, even in the longer term, monitored by international adult participation surveys (1997-2016), do not have high incremental dynamics. This development pattern is characterized by NFE participation stagnating or even showing signs of decline. None of the countries surveyed here in the long term dynamically grows above 69% (see Sweden in 2007), with the majority not exceeding 60% or more;

-

The Late NFE Adopters pattern, typical of the countries with a lower NFE participation rate (between 15-30%) at the beginning of the monitored period and in which the development of adult skills began to develop 'quantitatively' only later, especially between 2013 and 2016. On the contrary, it is characteristic for them that they tend to achieve larger increments of participants over time. E.g. in the twenty years since 1997, Italy and the Czech Republic have almost doubled the number of adults engaged in continuing education and training, while the proportion of adult learners in Scandinavian countries (e.g. Finland or Sweden) in 2016 was virtually comparable to the late 1990s.

The above-mentioned breakdown of the countries into 2 groups (Early NFE Adopters and Late NFE Adopters) is clearly shown in Figure

Problem Statement

Although there has been a significant increase in the average participation rate of adults in the NFE over the past 20 years (Desjardins, 2015, 2017; Rubenson, 2018), it should be noted that this increase is far from having affected all countries. On the contrary, it has been highly diversified. In the European Union, it is predominantly linked to an increase of participants in Late NFE Adopters countries. What is equally important is that this trend shows that there is a saturation threshold in the case of NFE.

It is typical of the saturation threshold that neither higher demand for nor higher supply of NFE leads to further involvement of adults in education and training. In the case of demand for NFE, this is due to the fact that, in line with the human resources theory, the share of actors in the population who are able and willing to educate themselves further or who have direct or indirect profits from this type of education is gradually decreasing (Becker, 1962, 1975; Psacharopoulos, 2006; Schultz, 1960, 1961). In the case of supply, this threshold is defined by the usability and return of the investment in education by institutions using the knowledge and skills coming from this education, which is most often employers (Brown, Green, & Lauder, 2001). In other words, despite its politically declared relevance as well as empirically documented benefits for both individual and collective actors, it is highly probable that the number of NFE participants has a certain growth threshold beyond which it cannot expand in the long term towards an imaginary utopian society of lifelong learning with all individuals being educated.

Based on these assumptions, this paper aims to focus on whether it is possible to empirically prove a trend towards the saturation of adult participation in one of the selected European Union countries - the Czech Republic, which is a typical country with the Late NFE Adopters development pattern (see Table

We believe that the focus of the paper is important for at least three reasons: first, from the point of view of knowledge of the developmental dynamics of NFE in the post-communist countries of Eastern Europe, or newly acceded states of the European Union; secondly, in terms of the formulation of a future effective education and social policy, since the existence of a saturation threshold has major implications for defining realistic objectives and indicators in the NFE policy. That policy cannot have more ambitious goals than the likely limits of adult participation. Thirdly, because of few analyses that focus on diachronic / developmental aspects of adult education systems (Milana, 2018).

With this focus in mind, we first specify our research objectives (Chapter 3), which we then supplement with refinement of the key mechanisms that affect NFE participation and interact with the saturation threshold (Chapter 4). In the following part of the text (Chapter 5) we will turn our attention to the description of the research file used and data analysis, while in the following chapter we present our main findings (Chapter 6). In the final part (Chapter 7) we discuss their theoretical and empirical implications, as well as the limits of the conducted survey and the possibilities of its further focus.

Research Aim

The main objective of the paper is to explore the development of saturation of adult participation in NFE in the Czech Republic in 2005-2016 and to discuss, using the available data, whether the NFE of adults in the current Czech Republic is approaching its growth limit or has the potential to further dynamically expand quantitatively.

Purpose of the Study

The key point of this paper is an application of a long-term approach to studying the development of NFE in the Czech Republic in an effort to identify its current trends and predict future ones. This can only be achieved if we are able to understand the threshold effects of adult participation in NFE and the factors that influence them further. Within this framework, we focus on a pair of very important and interrelated mechanisms that precondition long-term participation in NFE. They are partly the previous experience of adults with NFE and partly the intention of adults to participate in NFE. According to scientific literature (Keller, 2010; Crossan et al., 2003; Desjardins et al., 2006), both mechanisms operate as relevant predictors of further participation in NFE.

In the Czech Republic, the impact of previous NFE experience on adult participation in continuing education has been mentioned by a number of previous surveys (Kalenda, 2015a, 2015b; Rabušicová & Rabušic, 2008). The mechanism of its effect is based on the fact that experience with NFE reduces two types of highly frequented barriers to participation in NFE in the Czech Republic (Kalenda, 2016; Kalenda & Kočvarová, 2017). It is partly the weakening of the so-called personality barriers connected with the conviction of individuals that they would not manage further education, either due to lack of skills, education, age or other reasons, and partly it is information barriers. For them it is typical that potential participants in further education do not know where they could develop their skills, who could provide them with NFE, or what this activity will demand from them and what they can expect from it. If the NFE experience is lacking, they can easily develop various obstacles to the NFE which in turn reduce the NFE utility and the likelihood of their participation.

However, previous learning experience does not only make an important predisposition for NFE participation by reducing the perception of barriers. It also increases the predisposition to join NFE through the mechanism of 'chance accumulation' (Bask & Bask, 2015; DiPrete & Eirich, 2006). In other words, it affects the future intention of participating in NFE. The mechanism of the accumulation of chances is based on the argument that people who had previously participated in various forms of education and training and benefited from it in some way (e.g. by improving their skills, obtaining a compulsory certificate for the performance of their profession, etc.) are more likely to participate in this activity in the future. In this example, we can therefore see how the intent to participate in NFE and the previous experience of adult education are related. This empirical connection is also supported by some studies from the Czech Republic from 2005-2011 (AES, 2011; Rabušicová & Rabušic, 2008). At the same time, people who declare that they intend to participate in NFE in the future also participate in it more often (Kalenda, 2015a).

Both interrelated mechanisms also interact with the mechanism of saturation of participation in NFE - the saturation threshold. This is influenced precisely by the demand for NFE by adults (the intention to participate). Participation in NFE should therefore only increase, and to that extent, if there are a sufficient number of individuals in the population who have (1) participated in NFE in the past and are still interested in participating in the future; (2) have not participated in NFE recently, but are planning further participation in it in the future.

Research Methods

The paper is primarily based on secondary data on the participation of adults in NFE from four follow-up surveys conducted in 2005-2016. Firstly, it is the research “Adult Education in the Czech Republic” (CZ 2005), which was carried out within the research of the Rabusics (Rabušic & Rabušicová, 2006; Rabušicová & Rabušic, 2008). Secondly, it is the results of the AES surveys (2007, 2011, 2016) from 2007-2016 for the Czech Republic, which were carried out by the Czech Statistical Office. In all four cases, these are representative data for the Czech adult population. For the purposes of our analysis, we worked with a sample of the adult population aged 25-64 years, which corresponds to the major part of the adult population, which is already outside the formal education system and which is predominantly part of the economically active population.

The development of adult participation in NFE is mapped through the questionnaire item “I have participated in at least one NFE training activity in the last twelve months prior to the survey” (yes / no). The item also expresses the experience of the actor with NFE. In order to monitor future demand, we are working with a second important variable - the intention to participate in NFE (“I plan / do not plan to participate in education in the next twelve months”). In order to try to answer our research question, we use descriptive statistics that, in the context of the time series of percentage participation in NFE, allow us to monitor the key development trends in the chosen time period.

Findings

The development of adult participation in NFE in the Czech Republic is characterized by a slight increase from 1997 to 2005, from 27% to 35% (Kalenda, 2015b). Since that year, the involvement of adults in NFE has remained at the level of 35% for less than ten years to record a dynamic increase at the end of the monitored period. At that time, it achieved a record attendance of 45% (see Table

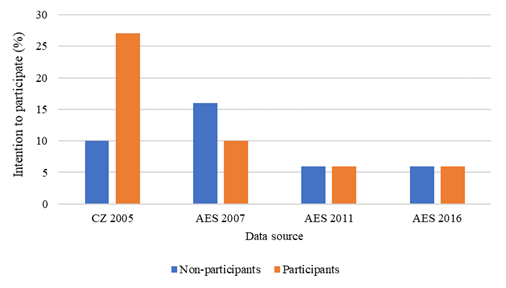

When comparing the two categories, we find that the number of people declaring an interest in continuing to participate in NFE declined by 24 percentage points in one decade, while the share of participants only increased by 20 percentage points. We can see quite well that the growth of adult participation in NFE was not sufficient to fully make up for the decline in the declared future demand for it.

Regarding the intention to participate in further education, a significant difference in the impact of previous experience with NFE can be identified from the beginning of the monitored period. In 2005, more than two thirds of adults planning to join NFE had direct experience with it. However, its influence disappears over time. It is clear from the results of the last two surveys, AES 2011 and AES 2016, that the gap between those who participated in the NFE and want to participate in the future and those without this experience has already completely disappeared, both groups being equal (see Table

Another important finding of our development-oriented analysis is an increase in the proportion of adults who have participated in NFE but who are no longer planning to participate in it. While in 2005 the share of these persons in the population was only 8% of adults, it continually increased to 39% over the next decade. In other words, the number of persons declaring their disinterest in participating in NFE nearly doubled in the given period, and today it is more than one in three adult Czechs. In contrast, the proportion of non-participants who do not plan to participate in the offered educational activities remained relatively constant throughout the period, ranging around half the adult population (49-59%).

Chart 2 shows a different view on the data, namely the decreasing percentage of respondents declaring their intention to continue to participate in NFE. The results are broken down into NFE participants and NFE non-participants. It is obvious that the greatest motivation for further participation in NFE was declared by participants in this type of education in 2005, and it has declined significantly since then. NFE non-participants declared the greatest intention to participate in the 2007 survey, but this also fell afterwards.

Conclusion

Theoretical implications

Please replace this text with context of your paper. Our results support the assumption of increasing saturation of demand for NFE in the Czech Republic, which is influenced by a dramatic increase in the number of individuals who do not intend to continue their education and training within NFE courses, these being not only from the group of adults who have never participated in NFE but also those who have already had experience with it and therefore should have fewer disposition and information barriers to participating in it (Felton-Busch, Solomon, McBain, & De La Rue, 2011; Flynn, Brown, Johnson, & Rodger, 2009).

In this respect, it can therefore be argued that with increasing saturation of the further education market, previous NFE experience ceases to have an impact on both planned adult participation and perception of barriers. In addition, it is entirely in line with the claims of Rubenson and Desjardins (2013) on the perception of barriers to education in countries with low and high adult participation in lifelong learning. In an international comparative analysis, the authors found that the degree of perceived barriers occurs with the same frequency in countries with high and low adult participation rates in lifelong learning. Therefore, previous experience with NFE does not necessarily lead to a reduction in disposition and information barriers, especially if the education in question was not beneficial for someone, overestimated his skills or did not show signs of sufficient quality.

Regarding an analysis of the future demand for NFE, it should be emphasized that in 2016 only about 13% of adults planned to participate. If we focus only on individuals who did not participate in this type of further education and whose participation could probably mean a higher future increase of participants, only 6% of adults planned to participate in NFE. Compared to the situation in 2005, this was a decline to almost one third of the original demand. In this respect, it is highly unlikely that adult participation in the Czech Republic could increase significantly.

In line with the central arguments of the classics of the theory of human resource development (Becker, 1962, 1975; Schultz, 1960, 1961), we believe that such a significant drop in NFE demand is associated with decreasing NFE utility attributable to four complementary factors. Firstly, NFE of adults in the Czech Republic does not have the same value as formal education outcomes in the Czech Republic, making some persons prefer to use an extensive publicly funded tertiary education system that expanded between 2004 and 2014 and that is widely available today (Prudký et al., 2010). In most cases, it is only within that system where one can obtain a recognized certificate of further vocational training which is recognized by employers. Secondly, adult skills are not an important tool in the Czech Republic either for gaining a job or for a higher remuneration provided by employers (Matějů & Anýžová, 2015). Therefore, participants in the labor market are more focused on other occupational strategies and career management than through systematic investment in developing their skills. Thirdly, the Czech labor market is currently very closed and has minimal unemployment as well as a high level of job protection. Thanks to this, as in the previous case, people are not very interested in joining NFE. Fourthly, where adults used NFE to develop their skills in the monitored period, they are likely to have done so at least once between 2005 and 2016 and therefore no longer have a need to use NFE and join it again. One of the reasons is that the Czech economy does not have as high requirements for the continuous development of work skills as the economies of the Western countries (Nölke & Vligenthart, 2009), where more persons are concentrated in the area of knowledge professions that require more systematic and permanent forms of workforce training (Brow et al., 2001).

Apart from the decrease of the NFE utility, we can identify a second important pattern in our results that, in our opinion, has an impact on the saturation of adult participation. It is the decreasing of the impact of NFE experience, or the weakening of the effects of the mechanism of cumulated chances (Bask & Bask, 2015; DiPrete & Eirich, 2006). As the number of participants increases, the impact of the previous involvement in NFE on the intention to participate in further education and training decreases. We believe that this phenomenon can be explained both by the structural (socio-economic) factors, described in detail in the previous paragraph, and by the fact that with the increasing number of individuals involved in NFE its exclusivity decreases in shaping the symbolically valued skills of an individual, as Pierre Bourdieu would say (1984), a specific form of cultural capital acquired through NFE, so there comes inflation of expected profits from it. Due to this inflation, therefore, fewer and fewer adults declare their willingness to engage in it, because it no longer constitutes a form of competitive advantage as at a time when far fewer participants are involved.

Practical implications

Our findings have important implications for the development of state policy in the field of adult education, which should not focus only on the overall level of participation in NFE as a primary indicator of equality / inequality in access to further education in the field, or as a prerequisite of an effective functioning of the whole system (PDV, 2010). The available data show that the Czech Republic is slowly approaching the maximum limits of participation in NFE and its further increase is unlikely. The priority should not be to increase the participation in NFE across the board, but to provide more targeted forms of assistance to social groups which have long been excluded from NFE and which could benefit significantly from it. These are mainly individuals who have not yet had direct experience with it and do not plan to participate in it, which continues to be more than half of adults. Most often they are low-skilled workers, seniors, persons on parental leave, and middle-aged working women, for whom NFE could be very suitable for improving their job status and financial income (Simonová & Hamplová, 2016), improving their quality of life, and reducing social inequality.

Limitations

The main limits of this study are several successive points. The first one is the very nature of the synthesis of data from several successive surveys on which our findings are based. Since we do not work with the results of longitudinal research on the same population, we are not able to trace variations in the change of individuals' experience with NFE and the intention to participate in further education in the context of their biographical paths. We describe only general patterns of participation and demand for NFE which are characteristic of representative groups of the Czech population between 2005 and 2016.

Another limitation of the time series analysis is the fact that we have a relatively short time series (five points), which is further distorted by the fact that it is not equidistant (the spacing of points in the time series is varied). It limits both the application of any time series analytical procedures (which we are aware of when applying the growth rate) and any prediction of future developments.

A secondary analysis allows to work only with variables based on questionnaires included in previous representative surveys at the national level (CZ 2005) or in international comparative surveys of adult participation in further education (AES 2007, 2011, 2016). In this context, our conclusions are therefore conditioned by the formulation and focus of the available items that we use to operationalize both the previous NFE experience and the perception of future demand for it. The time horizon of the used items, which deals with the period of 12 months before and after the survey, is particularly important. As a result, we are unable to trace the experience of participants with NFE that they may have had earlier (two or three years before) and that affected them, or the intention to engage in NFE beyond a period of one year.

Last but not least, our results are limited by focusing solely on the demand factor and not on the NFE supply. We have resorted to this focus because of the availability of more conclusive data from the available surveys and the possibility of their developmental comparison, as well as because of the overall scope of this study, which does not allow to address the issue in a sufficiently coherent manner.

Future directions

As part of further research, it would be appropriate to focus on the limits we have mentioned above, especially to explore in more detail the relationship between the intent to participate in NFE and the previous experience of individuals with NFE. With this in mind, such research should further address the previous biographical experience of adults in education, because if this experience is already negative in the early stages of the learning career, people later show less willingness to participate in further education (Crossan et al., 2003; Paldanius, 2007). Follow-up surveys should also deal with a greater number of variables that can affect NFE saturation, and not only those that interact with demand for NFE, but also those that interact more with adult NFE supply (e.g. unemployment rate, level of requirements for skills in the labor market, etc.). From a comparative perspective, the follow-up research should focus on two interrelated problems. First of all, on other countries that show the Late NFE Adopters formula, i.e. if they show the same dynamics of NFE demand reduction as in the Czech Republic, secondly, on comparing these countries with Early NFE Adopters that have a different developmental pattern and that have developed extensive NFE systems much earlier.

Acknowledgments

The paper was written with the kind support of the Czech Science Foundation through the project Blind Spots of Non-formal Education in the Czech Republic: Non-participants and their Social Worlds, GA_19-00987S.

References

- AES (2007). DV Monitor. Jak si stojíme v oblasti dalšího vzdělávání? Retrieved from http://www.dvmonitor.cz/iii-5-1-metodika/56-zdroje-dat/244-dalsi-vzdelavani-dospelych-adult-education-survey

- AES. (2011). Vzdělávání dospělých: specifické výstupy z šetření Adult Education Survey – 2011. Retrieved from https://www.czso.cz/csu/czso/vzdelavani-dospelych-specificke-vystupy-z-setreni-adult-education-survey-n-8d6jxtzxhj

- AES. (2016). Vzdělávání dospělých v České republice. Výstupy z šetření Adult Education Survey 2016. Retrieved from https://www.czso.cz/csu/czso/vzdelavani-dospelych-v-ceske-republice-2016

- Antikainen, A. (2006). In search of the Nordic model in education. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 50(3), 229-243.

- Bask, M., & Bask, M. (2015). Cumulative (dis)advantage and the Matthew effect in life-course analysis. PLOS ONE, 10(11). DOI:

- Becker, G. S. (1962). Investment in human capital: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 70(5), 9-49.

- Becker, G. S. (1975). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Biesta, G. J. (2011). Learning democracy in school and society: Education, lifelong learning, and the politics of citizenship. Rotterdam: Sense Publisher.

- Blossfeld, H. P., Kilpi-Jakonen, E., Vono de Vilhena, D., & Buchholz, S. (Eds.). (2014). Adult Learning in Modern Societies: Patterns and Consequences of Participation from a Life-course Perspective. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Boeren, E. (2016). Lifelong Learning Participation in a Changing Policy Context. An Interdisciplinary Theory. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Boeren, E. (2017). Researching lifelong learning participation through an interdisciplinary lens. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 40(3), 299-310.

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction. New York: Routledge.

- Brown, P., Green, A., & Lauder, H. (2001). High Skills: globalisation, competitiveness and skill formation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- CEC (Commission of the European Communities). (2012). Rethinking Education: Investing in Skills for Better Socio-Economic Outcomes. Brussels: European Commission.

- CEC (Commission of the European Communities). (2014). Promoting adult learning. Brussels: European Commission.

- Crossan, B., Field, J., Gallacher, J., & Merrill, B. (2003). Understanding participation in learning for non-traditional adult learners: Learning careers and the construction of learning identities. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 24, 55–67.

- Desjardins, R. (2015). Participation in adult education opportunities, Evidence from PIAAC and Policy trends in selected countries, background paper for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2015.

- Desjardins, R. (2017). Political Economy of Adult Learning Systems. Comparative Study of Strategies, Policies, and Constraints. London: Bloomsbury.

- Desjardins, R., & Rubenson, K. (2013). Participation Patterns in adult education: The role of institutions and public policy frameworks in resolving coordination problems. European Journal of Education, 48(2), 262–280.

- Desjardins, R., Rubenson, K., & Milana, M. (2006). Unequal Chances to Participate in Adult Learning: International Perspectives. Paris: UNESCO.

- DiPrete T. A., & Eirich, G. M. (2006). Cumulative Advantage as a mechanism for inequality: A review of theoretical and empirical developments. Annual Review of Sociology, 32(1), 271–297.

- EDG (2015). Education at a Glance. Paris: OECD.

- Felton-Busch, C. M., Solomon, S. D., McBain, K. E., & De La Rue, S. (2009). Barriers to advanced education for indigenous Australian health workers: An exploratory study of Education for Health Change., Learning and Practice, 22(2), 187.

- Field, J. (2006). Lifelong Learning and the New Educational Order. Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books

- Flynn, S., Brown, J., Johnson, A., & Rodger, S. (2011). Barriers to education for the marginalized adult learner. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 57(1), 43–58.

- GRALE (2013). Second Global Report on Adult Learning and Education. Retrieved from http://uil.unesco.org/adult-education

- GRALE (2016). Third Global Report on Adult Learning and Education. Retrieved from http://uil.unesco.org/adult-education

- Green, A. (2006). Models of lifelong learning and the knowledge society. Compare, 36(3), 307–325.

- Green, A. (2011). Lifelong learning, equality and social cohesion. European Journal of Education, 46(2), 228–243.

- IALS (2000). Literacy in the Information Age. Final Report of the International Literacy Survey. Paris: OECD.

- Kalenda, J. (2015a). The Issue of Non-formal Adult Education in the CZE. Asian Social Science, 11(3), 37-48.

- Kalenda, J. (2015b). Development of non-formal adult education in the Czech Republic. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174, 1077–1084.

- Kalenda, J. (2016). Education Barriers for Czech Adults. The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 10(4), 754–765.

- Kalenda, J., & Kočvarová, I. (2017). Proměny bariér ke vzdělávání dospělých v České republice: 2005-2015 [Transformation of Barriers towards Adult Education in the Czech Republic]. Studia Paedagogica, 22(3), 69–89.

- Keller, J. M. (2010). Motivational Design for Learning and Performance: The ARCS Model Approach. New York, NY: Springer.

- Matějů, P., & Anýžová, P. (2015). Role lidského kapitálu v úspěchu na trhu práce: srovnání šesti evropských zemí participujících na PIAAC [The Role of Human Capital in Success in Labour Market: Comparision of European Coutries Participated in PIAAC]. Sociológia, 47(1), 31–65.

- Milana, M. (2018). Research Patterns in Comparative and Global Policy Studies on Adult Education. In M. Milana et al. (Eds). The Palgrave International Handbook on Adult and Lifelong Education and Learning (pp. 421–441). London, UK: Palgrave.

- Nölke, A., & Vligenthart, A. (2009). Enlarging the Varieties of Capitalism. The Emergence of Dependent Market Economies in East Central Europe. World Politics, 61, 670–702.

- Paldanius, S. (2007). The rationality of reluctatnce and indifference toward adult educcation. Proceeding of the 48th Annual American Adult Education Research Conference, 48, 471-476.

- PIAAC. (2013). Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/

- Psacharopoulos, G. P. (2006). The value of investment in education: Theory, evidence and policy. Journal of Education Finance, 32, 113–126.

- PDV. (2010). Průvodce dalším vzděláváním [Guide to Further Education]. Praha: Ministerstvo školství mládeže a tělovýchovy.

- Rabušic, L., & Rabušicová, M. (2006). Adult Education in the Czech Republic – Who Participates and Why. Czech Sociological Review, 42(6), 1195–1218.

- Rabušicová, M., & Rabušic, L. (Eds.). (2008). Učíme se po celý život? O vzdělávání dospělých v České republice [Do We Learn a Whole Life? About Adult Education in the Czech Republic]. Brno: Masarykova univerzita.

- Rees, G. (2013). Comparing Adult Learning Systems: an emerging political economy. European Journal of Education, 48(2), 200–212.

- Regmi, K. D. (2015). Lifelong learning: Foundational models, underlying assumptions and critiques.International Review of Education, 61(1), 133–151.

- Riddell, E., Markowitsh, J., & Weedon, E. (Eds). (2012). Lifelong Learning in Europe. Equity and efficiency in the balance. Chicago, IL: The Policy Press.

- Roosmaa, E-L., & Saar, E. (2010). Participation in non-formal learning: Patterns of inequality in EU-15 and the new EU-8 member countries. Journal of Education and Work, 23(3), 179–206.

- Roosmaa, E-L., & Saar, E. (2017). Adults who do not want to participate in learning: a cross-national European analysis of their barriers. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 36(3), 254–277

- Rubenson, K. (2018). Conceptualizing Participation in Adult Learning and Education. Equity Issues. In M. Milana et al. (eds). The Palgrave International Handbook on Adult and Lifelong Education and Learning (pp. 337–357). London: Palgrave.

- Rubenson, K., & Desjardins, R. (2009). The impact of welfare state requirements on barriers to participation in adult education: A bounded agency model. Adult Education Quarterly, 59(3), 187–207.

- Prudký, L., Pabián, P., & Šíma, K. (2010). České vysoké školství na cestě od elitního k univerzálnímu vzdělávání: 1989-2009. [The Czech Higher Education on the Road from Elite to Universal Education: 1989 - 2009]. Praha: Grada Publishing

- Saar, E., & Räis, M. L. (2017). Participation in job-related training in European countries: the impact of skill supply and demand characteristics. Journal of Education and Work, 30(5), 531–551.

- Saar, E., Ure, O. B., & Desjardins, R. (2013). The Role of Diverse Institutions in Framing Adult Learning Systems. European Journal of Education, 48(2), 213–232.

- Sen, A. (1997). Editorial: Human capital and human capability. World Development, 25(12), 1955-1961.

- Schultz, T. W. (1960). Capital formation by education. Journal of Political Economy, 68(6), 571-583.

- Schultz, T. W. (1961). Investment in human capital. The American Economic Review, 51(1), 1-17.

- Simonová, N., & Hamplová, D. (2016). Další vzdělávání dospělých v České republice – kdo se ho účastní a s jakými výsledky? [Further Education of Adults in the Czech Republic - Who is participating and With What Results?]. Sociologický časopis, 52(1), 3–25.

- Verdier, E. (2017). How are European lifelong learning systems changing? An approach in terms of public policy regimes. In R. Normand, & J-L. Derouet (Eds.), A European Politics of Education. Perspectives form sociology, policy studies and politics (pp. 194-215). London: Routledge.

- Verdier, E. (2018). Europe: Comparing Lifelong Learning Systems. In M. Milana et al. (Eds.), The Palgrave International Handbook on Adult and Lifelong Education and Learning (pp. 461-483). London: Palgrave.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

07 November 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-071-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

72

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-794

Subjects

Psychology, educational psychology, counseling psychology

Cite this article as:

Kalenda, J., & Kočvarová, I. (2019). Approaching Limits Of Participation? Trends In Demand For Non-Formal Education In The Czech Republic. In P. Besedová, N. Heinrichová, & J. Ondráková (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2019: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 72. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 611-624). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.11.71