Abstract

Since 2010, ethical education has been a part of the Czech Framework Educational Program for Primary Education as a supplementary educational field (FEP PE). The resulting concept of ethical education is based on the theory of Professor Roberto Roche Olivar and Ladislav Lencz. The aim of the paper is to describe the first part of the research, which verified and validated the methodological procedures in connection with the research hypothesis. In our pre-research, we tried to verify in the context of Czech primary school, whether the ethical education has a major impact on raising the level of moral competence and whether there are differences in the level of moral competence of pupils who have or do not have ethical education. Methodologically, we applied the Moral Competence Test (MCT) of the German psychologist Georg Lind.

Keywords: Ethical educationmoral competenceprimary school

Introduction

The end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century significantly revived the interest in ethical and moral education. The evidence can be found not only in the form of the establishment of various professional associations, but also in the national curriculum change. These statements are based on an analysis of the situation in the Czech Republic and in the countries of Central Europe. We can assume that this increased intensity of interest in ethics and morality is caused by a certain crisis (L. Muchová in this context explicitly writes about the crisis of the family, the social state, peace and justice and the crisis in ecology and economics (Muchová, 2015, p. 8-22).) in society, or in human relations. There are undoubtedly many causes of the current situation, but in general, we can say that the dynamics of the changes is so intensive that it might cause problems for more people than in the past. There is thus a value, opinion and argument discrepancy, which in turn has a negative effect on all members of the society.

The need for a coherent conception of ethical and moral education, as part of the national curriculum of individual EU countries, appears as very urgent. For example, if we want to build understanding and cooperation between states and their citizens by pointing out common values, then we must guarantee that everyone understands the true nature of this value (and not only its superficial meaning). Ethical education at primary schools should therefore also lead to this aim.

There are several researches that verify the “effectiveness” of ethical education among individual actors of the educational process. E.g. Motyčka (2014) examined the level of prosocial behaviour of pupils having the ethical education; Kunstová (2015) focused on the ethical education teachers and their problems in teaching. Psychological aspects of pupils' moral reasoning have long been addressed by Vacek (eg. 2000, 2008, 2013).

Historical parallels

The requirement on theory and philosophy of education to systematically deal with ethics and moral education has a long tradition. The first notes can be found in the works of ancient philosophers. Aristotle addressed the issue of the ethical dimension of man in the most complex way. In his Ethics Nikomachos he writes that all human action should be directed to the good, and the greatest good is blessedness. Ethical behaviour is then in accordance with reason (see Aristotelés, 1996, p. 25-66).

In the 17th and 18th century, a significant progress was made towards the educational application of ethics, when the works of Comenius and Rousseau were published. J. A. Comenius described his idea in the book Didactica magna (1948), J. J. Rousseau in the publication Emil, or On Education. The first of the authors comes in the chapter "Method of Morals" with 16 rules for youth education to morals, based on the four original ancient virtues of wisdom, moderation, bravery and justice, but defines them differently than e. g. Aristotle (see Comenius, 1948, p. 177-182). Rousseau, on the other hand, who disputes Locke with regard to the moral education attitude, gives a typical example of a child questioning an adult. According to the author, this discussion, in which the child asks for the cause and meaning of virtuous behaviour, inevitably ends in a vicious circle that he: “cannot avoid”. The worst end he sees in a moment when the child acquires the act of pretense and lie for reward, or avoidance of punishment (see Rousseau, 1926, p. 105-107).

The turn of 19th and 20th century is marked by serious theories, researches and conclusions in the field of ethical and moral education. The educational dimension is enriched with ideas from psychology, medicine or social sciences. We can mention in particular the work on cognitive theories of moral development by J. Piaget, L. Kohlberg, J. Rest, L. Selman, or G. Lind. Based on their research, these authors presented their own view of the moral development of man and also tried to suggest a way of its measurement. In our paper we focused on George Lind's theory and his method of determining a moral competence.

Problem Statement

The aim of the paper is to describe the first part of the research, which verified and validated the methodological procedures in connection with the research hypothesis. In our pre-research, we tried to verify in the context of Czech primary school, whether the ethical education has a major impact on raising the level of moral competence and whether there are differences in the level of moral competence of pupils who have or do not have ethical education. Methodologically, we applied the Moral Competence Test (MCT) of the German psychologist Georg Lind.

Research Questions

Since 2010 has been ethical education as a part of the Framework Educational Program for Primary Education. Therefore, we have formulated the main research question as follows: Are there differences in the level of moral competence of pupils who have and do not have ethical education?

Purpose of the Study

One of the purposes of the study is to find out how ethical education has influenced the level of moral competence of pupils on the primary school.

In this study we will characterize the pilot study, which took place within the project of the internal grant competition of the Faculty of Education, Palacký University in Olomouc (IGA) entitled Paradigm of Ethical Education and Ethical Literacy. The aim of the pilot study was to verify the suitability of using the Moral Competence Test (MCT) method for achieving the project aims. The following research part expects about three times higher number of respondents in each of the monitored groups.

Research Methods

Moral Competence Test (MCT)

German psychologist Georg Lind has long been involved in measuring moral competence. He developed the Moral Competence Test (MCT), which is based on the dual aspect theory of moral behaviour. Methodologically, it is based on the theory of cognitive algebra, developed by American psychologist Norman H. Anderson, which through a mathematical formula records the overall impression of the other person. Furthermore, this method is based on the theory of personal constructs, created in 2001 by American psychologist Georg A. Kelly. This theory deals with how a person recognizes, plans and acts in everyday situations, what hypotheses he/she makes and how he/she tests and validates them. This hypothesis, which Kelly names as personality constructs, has a significant influence on individual behaviour and his/her actions. Furthermore, the method is influenced by the theory and methodology of scaling, developed by psychologist Warrene S. Torgerson in 1958. The theory summarizes, streamlines and simplifies a large amount of information into a simple and unified record. The latest methodology on which MCT is based is a method that helps to organize the questions in a questionnaire to achieve the highest possible coherence and validity. This method was compiled by the prominent American and Israeli psychologist Louis Guttman in 1955 (LIND, G. (2019) How to Teach Morality. Promoting Deliberation and Discussion, Reducing Violence and Deceit. With Discussion. [online].) .

The structure of MCT consists of two moral dilemmas that are based on the story of a worker and a doctor. The first story describes a dilemma in which workers suspect their management to eavesdrop them. Some of the workers, therefore, decide to break into the manager's office and get the recordings. The second story is about a seriously ill patient who no longer has a chance of recovery, suffering great pain and begging her doctor to end her life because she no longer manages to endure the pain. After reading the story, the respondent evaluates on a scale of -3 to + 3 how much they agree or disagree with the indicated behaviour of the workers or the doctor. Subsequently, there are six arguments in the questionnaires to support workers' actions and a doctor and six arguments against these actions. The respondents evaluate these arguments on a scale of -4 to +4, depending on how strongly they agree or disagree. A value of -4 means that the respondent absolutely disagrees with the argument and a value of +4 indicates absolute consent (LIND, G. (2011). Measuring Moral Judgment Competence With the Moral Judgment Test (MJT). [online].

) . If respondents answered individual questions and marked their answers in a questionnaire, the result is a C-score that determines the moral competence of the group. This C-score is calculated according to a table compiled by Professor Georg Lind.

This method is intended only for group diagnosis and not for individuals. The author of the method states that the respondents may be tired when completing the questionnaire, may not feel well, may also be emotionally disturbed, stressed or may be influenced by other circumstances that have a negative effect on the resulting value. For this reason, this method is intended for a group of 15 or more people, since the adverse effects are minimized and thus not essential to the group results (LIND, G. (2019) How to Teach Morality. Promoting Deliberation and Discussion, Reducing Violence and Deceit. With Discussion. [online].) .

Findings

The MCT questionnaire was distributed in the school year 2018/2019 at three primary schools in the Czech Republic, two primary schools were selected from the South Moravian Region and one primary school from the Olomouc Region. As part of this pre-research, we set the following criteria: at least 40 respondents who have ethical education in their school educational program (hereinafter referred to as SEP) and 40 respondents who do not have ethical education in their SEP would participate in fulfilling the questionnaire. Schools participating in this study are the Church Primary School in Veselí nad Moravou (40 respondents), the Primary School and the Kindergarten of Jan Ámos Komenský in Žeravice (7 respondents) and the Primary School in Troublice (33 respondents). The Church Primary School in Veselí nad Moravou has ethical education included in its SEP, the other two schools do not have ethical education.

The questionnaires were distributed only to pupils of the 9th grade (14-15 years old), because this age group in primary school seemed to be most relevant in assessing and evaluating individual moral dilemmas. The questionnaire was anonymous, pupils filled in only their gender and age as personal data. They then evaluated the answers or arguments in the test according to the mechanism described above.

The Church Primary School in Veselí nad Moravou has included the ethical education in its School Educational Program since 1st September, 2008. Ethical education is realized in a form of one lecture per week for all years. In 2016, the school succeeded in the Program of Support of Ethical Education of the Foundation of Josef Lux and won 1st place in this competition. Teaching of the subject of ethical education is realized in cooperation with the parish Veselí nad Moravou. The main aim is to educate an active citizens of our country who are willing to engage in the social activities.

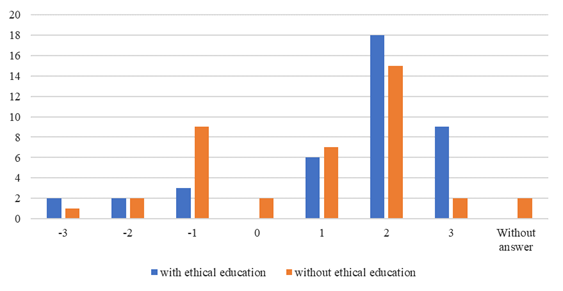

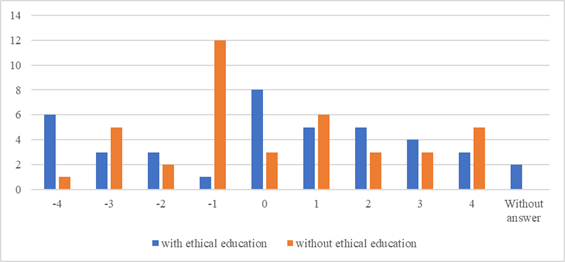

We further processed the respondents' answers and set their frequencies. Subsequently, we entered the frequencies into graphs for better visualization. The results show that the moral dilemma of the workers who chose to procure the evidence was rated by the majority of all respondents as positive and the respondents rather agree with this behaviour. Positive values are very similar for both groups of respondents, 34 respondents having ethical education in SEP agree with this behaviour as well as 24 respondents who do not have ethical education. The highest number of all respondents (33) rated this behaviour by +2 - rather agree. The lowest number of answers was 0 (I do not know), which the group of respondents from the Church Primary School in Veselí nad Moravou did not choose and the respondents from the second group chose this option twice. Out of the 80 respondents, only 2 did not answer this question (see figure

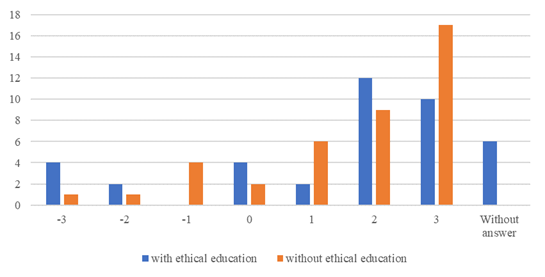

Other results were related to the second moral dilemma - a doctor who met the wish of his patient who wanted to end her life because she no longer had a chance of recovery and suffered from very severe pain. The results reaffirmed that both groups of the respondents had a very similar opinion on the doctor’s behaviour. Out of a total of 80 respondents, 57 pupils answered positively and agreed with the doctor’s behaviour; only 6 respondents did not answer the question. The highest number of answers was +3 (fully agree) and the lowest number was -2 (rather disagree) on the negative part of the scale. Of the total number, 6 respondents were unable to decide on this question and chose an answer with a value of 0. Respondents who do not have ethical education, answered 32 positively and 24 respondents not having the ethical education answered also positively. The value -1 was not represented in the answers of pupils having the ethical education (as shown in Figure

Differences in views on arguments in MCT

Furthermore, individual arguments for and against the behaviour of the workers and doctor were processed and evaluated on a scale of -4 to +4. Only five arguments were selected for this study, with statistically significant differences in response rates among respondents who did and who did not attend the ethical education.

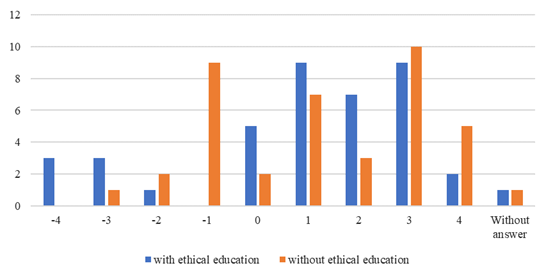

Most of the different responses were related to the argument supporting workers' behaviour, which viewed their behaviour as a minor offense in comparison to that one committed by the management of the company. Respondents who do not have an ethical education chose the value of -1 nine times and respondents who have an ethical education did not choose this value at all. Compared to 12 respondents not having the ethical education, respondents having the ethical education had 6 responses on the negative scale of this argumentation. It can therefore be stated that pupils who have completed ethical education are more tolerant in the case of wrongful behaviour of workers than pupils who have not attended the ethical education program (see Figure

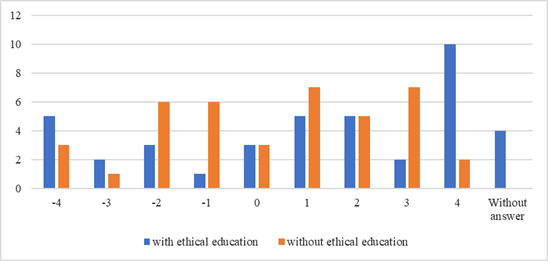

In the part, which consists of 6 opinions condemning the behaviour of workers, there was the greatest difference in the number of responses to the idea that insisted on absolute respect for private property. Negative values (from -4 to -1) were more frequently chosen by respondents who do not have ethical education. Altogether, 17 respondents from the group not having ethical education chose these negative values and only 5 respondents of group having the ethical education chose these negative values. Specifically, the highest difference was in the negative value of -1, which was chosen nine times by a group of respondents who do not have ethical education and only twice by the respondents from the second group (see Figure

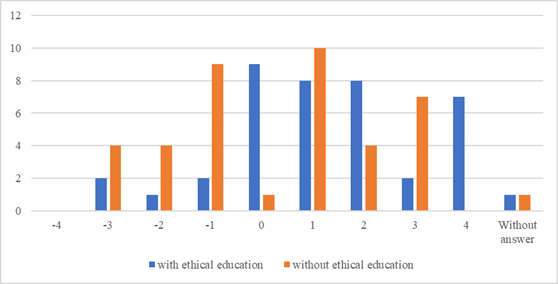

Another significant difference was noted in the part concerning the behaviour of the doctor. The argument supporting his behaviour corresponded to the probability of similar behaviour of his colleagues. Here, the biggest difference regarded the value -1. Respondents who do not have an ethical education answered 12 times in this way, the respondents from the second group answered only once. Overall, pupils who do not have an ethical education were more negative than respondents from the second group. The difference was 7 negative answers (as shown in Figure

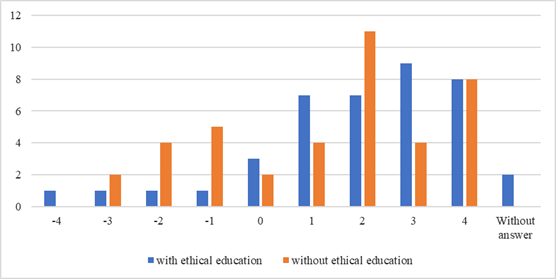

Even more significant difference in the evaluation of the doctor's behaviour was in the appeal to the highest moral mission of the doctor - saving human life. Absolutely agreed (+4) 10 respondents from the group having ethical education and only two respondents from the second group agreed with this statement. Overall, the number of respondents who evaluate positively this statement is very similar, 22 respondents having ethical education and 21 respondents not having the ethical education (see figure

In the case of negative responses, the greatest difference between the follow-up and the control groups regarded the moral dilemma of the doctor who wanted to help the patient to die. 11 respondents who do not have an ethical education disagreed with this attitude as well as 4 respondents from the second group (see Figure

Conclusion

In our research we focused on the level of solving moral dilemmas according to the MCT method of G. Lind. The sample of respondents were pupils who had completed ethical education and a control group who did not have ethical education at primary school. Based on our findings, we can say that only 5 out of the 24 statements that are part of the MCT have significantly higher differences in responses between groups of pupils. The remaining arguments which G. Lind submits for consideration are evaluated by both groups in a similar way. This leads us to the conclusion that the level of moral competence is not fully dependent on completing the ethics program at primary school. Nevertheless, it can be said that the moral feeling of pupils who have completed ethical education is generally higher than that of other pupils.

In the next phases we want to present the results of the whole research (including comparison of the C-index in the follow up and control groups) in a significantly higher sample of respondents. Above all, we want to formulate the concept of ethical literacy, which is currently being developed at the Department of Social Sciences of the Faculty of Education, Palacký University in Olomouc.

Acknowledgments

The paper has been funded by IGA project of Palacký University in Olomouc named: Paradigm of the Ethical Education and Ethical Literacy; IGA_PdF_2019_014.

References

- Aristotelés (1996). Etika Níkomachova. [Nicomachean Ethics]. Praha: Petr Rezek.

- Komenský, J. A. (1948). Didactica magna. [Didactica magna]. Retrieved from https://monoskop.org/images/3/3e/Komensky_Jan_Amos_Didaktika_velka_3_vydani_1948.pdf

- Kunstová, J. (2015). Etická výchova a její realizace v podmínkách českých a slovenských základních škol na úrovni nižšího sekundárního vzdělávání (ISCED 2). [Ethical Education and its Attainment under the Conditions of Czech and Slovak Primary Schools on the Level of Lower Secondary Education (ISCED 2)] (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://theses.cz/id/cy35h5/KUNSTOVA_JAROSLAVA_-_disertacni_prace_-_autoreferat.pdf .

- Lind, G. (2011). Measuring Moral Judgment Competence with the Moral Judgment Test (MJT). Retrieved from: http://www.uni-konstanz.de/ag-moral/material/dias-english/3_MJT.pdf

- Lind, G. (2019). How to Teach Morality. Promoting Deliberation and Discussion, Reducing Violence and Deceit. With Discussion Theater. Berlin: Logos. Retrieved from http://www.uni-konstanz.de/ag-moral/buch-lind/target35.html.

- Motyčka, P. (2014) Implementace doplňujícího vzdělávacího oboru Etická výchova v České republice. [Implementation of Ethic Education as a Supplementary Educational Subject in the Czech Republic] (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://is.cuni.cz/webapps/zzp/detail/93244/

- Muchová, L. (2015) Morální výchova v nemorální společnosti? [Moral education in immoral society?] Brno: Centrum pro studium demokracie a kultury.

- Rousseau, J. J. (1926). Emil čili o vychování. [Emile, treatise on Education]. Olomouc.

- Vacek, P. (2000). Morální vývoj v psychologických a pedagogických souvislostech. [Moral development in psychological and pedagogical context]. Hradec Králové: Gaudeamus.

- Vacek, P. (2008). Rozvoj morálního vědomí žáků. [Development of moral consciousness of pupils]. Praha: Portál.

- Vacek, P. (2013). Psychologie morálky a výchova charakteru žáků. [Psychology of morality and education of pupils character]. Hradec Králové: Gaudeamus.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

07 November 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-071-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

72

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-794

Subjects

Psychology, educational psychology, counseling psychology

Cite this article as:

Hubálek, T., & Rajsiglová, A. (2019). Moral Competence As Part Of Ethical Literacy. In P. Besedová, N. Heinrichová, & J. Ondráková (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2019: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 72. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 592-601). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.11.69