Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to review about the influence of crisis management on customer purchase intention towards cosmetic and healthcare products. We develop model based on a review of previous research on the elements of crisis management, such as time, responsible recall, opportunistic recall, blame attributes, perceived responsibility of organization in crisis and customer purchase intention after crisis. The model can be used to understand customer purchase intention after each crisis that occurred after the organization. A product-harm crisis can raid an organization whenever, wherever which could genuinely deliver harms and claims to the organization, affect its feasibility, losses to the shareholders, turning devastating event into a catastrophe to the general public, and even the environment. The number of product-harm crisis in Malaysia in the present market is rising due to factors like the increasingly complex products, the evolvement of product-safety legislation. An organization should prepare with operative and effective crisis management and crisis communication plans that can support their execution of crisis management. The significant of this study lies on the fact that it will provide vital insights on how time, responsible recall, opportunistic recall, blame attributes, perceived responsibility of organization affect the purchasing intention of customer.

Keywords: Timeresponsible recallopportunistic recallblame attributionperceived crisis responsibilitycrisis communication

Introduction

Products becoming increasingly complex, the evolvement of product-safety legislation, and the changing customer demands and preferences are among the major contributors to the rising number of product-harm crises in the present market place (Cleeren, 2015). This trend is in line with the statements by Dawar and Pillutla (2000) and Dawar and Lei (2009) that there was a significant increase of the number of defective, unsafe, or harmful products recalled from the market in the last few years. In the European Union market alone, the total number of non- food dangerous product notifications was 2,125 in 2015, an increase of 1,278 in a span of ten years (RAPEX, 2016).

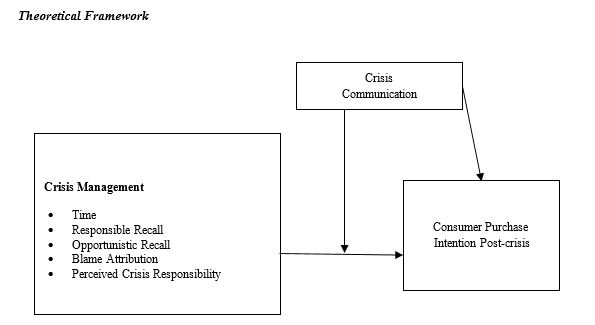

Interestingly, majority of previous studies were concentrating on the factors influencing customer response in a product-harm crisis (Vassilikopoulou et al., 2009; Magno, 2012). Nevertheless, there is no clear indication on the moderating role of crisis communication on the relationship between crisis management and customer purchase intention post-crisis in previous studies. Therefore, this research is conducted to contribute to stream of researches on crisis communication and crisis management, consisting of the moderating role of crisis communication on the relationship between crisis management and customer purchase intention post-crisis.

Problem Statement

A crisis can attack a company at any moment, and no matter when. When crises arise, it will affect not just to its feasibility, but also people involve in that organization like investors, public whom keeping eyes on them, and even to the surrounding. Briefly explain, a crisis is described as an important threat to any operations. As mentioned by Coombs (2007) if the crisis is not handled correctly, it can lead to many negative consequences. Crises can attack company regardless the size of the organization. Avlon, a famous brand is one of the good example of product tampering cases that has impact their customers trust and confidence. This happen when their product found to be contaminated with the bacteria Enterobacter cloacae. Next is famous teenagers’ brand, Claire, who has claimed to possess asbestos in its product, and Oral essentials, who had to recall their merchandises as it has potential Pseudumonas aeruginosa contamination. Apart from these, there’s numerous crises that hit companies around the world but never get public’s and media’s attention.

If the crisis happened and the management did not handle them properly, a business may face a huge loss (Arpan & Pompper, 2003). Coomb (2007) also shared that every crisis arise can cause in three related threats. They are consumer safety, few losses like financial and reputation loss. Accidents and fatal are some of the consequences from product-harm that happened in the industry. When crisis happen, any businesses may suffer from problematic operations, or even lost their market share. It might also affect consumer purchase intentions and leads consumer to filing a lawsuit which might threatening the organization with financial loss. Dilenschneider (2000) cited that all crises are threatening to forfeiture every business reputation.

Mitroff and Alpaslan (2014) remarked that uncontrollable reactions could also strike together with the crisis and thus, organization need to come out with a good preparation to control and solve crises at the same time. This preparation to tackle crises is refer as crisis management. Crisis management is an organization’s advance preparation and strategies in preparing themselves to respond to crisis and incidents cases like severe storms, fires, earthquakes, acts of terrorism, workplace violence, flop threats, contamination in products, kidnappings, and in an unharmed and constructive means (Lockwood, 2005).

Interestingly, majority of previous studies were concentrating on the factors influencing customer response in a product-harm crisis (Vassilikopoulou et al., 2009; Magno, 2012). Nevertheless, there is no clear indication on the moderating role of crisis communication on the relationship between crisis management and customer purchase intention post-crisis in previous studies. Therefore, this research is conducted to contribute to stream of researches on crisis communication and crisis management, consisting of the moderating role of crisis communication on the relationship between crisis management and customer purchase intention post-crisis.

Research Questions

The main objective of this thesis is to investigate and determine how perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, perceived risks, trust, price, informational social influence and e-WOM (electronic word of mouth) affects the purchasing intentions of online customers towards online-group purchasing websites.

Purpose of the Study

The aim of this research is to assess the customers’ views on the elements of crisis management, such as time, responsible recall, opportunistic recall, blame attribution, and perceived responsibility of organization in crisis on customer purchase intention after crisis, moderated by crisis communication.

4.1. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Following the framework from previous studies (Klein & Dawar, 2004; Laufer et al., 2005; Vassilikopoulou et al., 2009), consumers’ perception about crisis management will have an impact on consumers’ purchase intention post-crisis. Therefore, this study will include crisis communication in the theoretical model. It will act as an independent variable and a moderator to evaluate its significance on consumer purchase intention post-crisis and the relationship between crisis management and consumer purchase intention post-crisis. Consumers will be able to make informed judgment after observing the overall crisis management and crisis communication carried out by a company as the crisis takes place and possess more crisis information. On top of it, past studies also evaluated consumer response post-crisis in their theoretical models (Figure

4.1.1. Crisis Management

Crisis management is separated into three phases, which are (1) pre-crisis, (2) crisis response, and (3) post-crisis (Coombs, 2007). The beginning part is before or also known as pre-crisis that more focusing on how to prevent and what to prepare to handle crisis. Next part is crisis response, which focusing during the crisis, is unquestionably will replace organization’s management in dealing with the crisis. The last part, which is after or also known as post-crisis. This is where the management will take action to evaluate their crisis management, preparation for the next incident. At the same time, the company needs to ensure they are fulfilling their commitments or any promises done during the crisis. Follow up on crisis should be shared with related parties, like public and its consumers. By using constructive crisis management in handling crisis, it helps to protect company’s reputation and control bad publicity, which is damaging for the organization (Stafford et al., 2002). As mentioned by Regester (1989), fundamentals for crisis management includes anticipation, expectation, preparation, and trainings. A useful crisis management needs active communication with related parties. For instance, shareholders, politicians, the financial teams, pressure groups, agencies related to government, and shareholders or anyone who has interest in the achievement and catastrophe of respective company.

Purchase intention is define as customer willingness to buy a service or a certain product. It is also described as the possibility that a customer will buy a specific product; where the higher the purchase intention, the greater the purchase probability will be (Dodds et al. 1991; Schiffman & Kanuk, 2000). Therefore, customer purchase intention post-crisis is well-described as the customer willingness to buy affected company’s products once the crisis is over. Therefore, the development of the following hypothesis:

H1: Crisis management has significant influence on customer purchase intention post-crisis.

4.1.2. Time

The meaning of time in this study is the difference between the first signals of product dangerousness and the withdrawal from the market, time taken to react promptly to the crisis issues and quick response to inquiries is most vital. It is an integral element of crisis management of an organization during a product-harm crisis which fall to be the main focus of this study and aims to validate the results of previous studies that make use of similar definition of time (Mowen, 1980, Magno et al., 2010 and Magno, 2012). They discovered that time has important influence on post-recall vein of consumers, consumer perceptions towards the organization, as well as customer purchase intentions after crisis.

There are many definitions used by scholars like the time period without the crisis, the year of the sale of the product and the utterance of its recall. Time is described as the difference between the first signals of product dangerousness and the time it’s been pulling out from the market, time taken to respond quickly to the crisis issues and fast response to consumer inquiries (Mowen, 1980; Standop, 2006; Roth et al., 2008; Hora et al., 2011 & Magno, 2012) and as the time period without the crisis (Vassilikopoulou et al., 2009), the year of the deal of the product and the statement of its recall (Roth et al., 2008 & Hora et al., 2011). Conversely, Johnson-hall (2012) termed and classified time into three stages which are Stage 1: end of production to time of defect detection, Stage 2: time of defect detection to public announcement, and Stage 3: public notification to the closure of recall activities which comprises reverse logistic processes by the recalling firm and recall monitoring by the regulatory and used the term time to recall by combining the first two stages. Therefore, the following hypothesis was formed:

H1a: Time has significant influence on customer purchase intention post-crisis.

4.1.3. Responsible Recall

Responsible recall or crisis response is one of the key factors, instrumental in defining the success of an organization in dealing with a crisis situation. A responsible recall is pinpoint as a product recall made by an organization before governmental intervention or also known as voluntary recall and super-effort. Product recall is described as the process provided in law that which is adopted by suppliers in recalling consumers. This is due to faults or defects found in either products or services in the market (Consumer Defence Protection Foundation – PROCON, 2014). For instance, ease of recall process, wide recall advertisement and offering compensation (Jolly & Mowen, 1985; Siomkos, 1989; Shrivastava & Siomkos, 1989; Siomkos & Kurzbard, 1994; Magno, 2012).

Products that have quality failure findings has been released for distribution and consumption and are well publicized will result in product recall (Johnson-hall, 2012). A usual product recall process normally involves repairing or withdrawing defective product. It comes with the objective to resolve reduce impact public safety issues (Carrol, 2016). Therefore, the hypothesis below was developed:

H1b: Responsible recall has significant influence on customer purchase intention post- crisis.

4.1.4. Opportunistic Recall

Opportunistic recall is also defined as product recall, which meant to be done with opportunistic attitude. By conducting product recall due to external pressures such as governmental intervention, it should be categorised as involuntary recall and falls under opportunistic recall. This includes the company trying to take advantage from the crisis happen by making their customers used one of its other products, increase brand awareness not just to other products but also on affected products, hiding the actual product issues, and doing the recall only because of external pressures besides after being found out by external parties (Magno, 2012).

Whenever a company involuntarily recalls their defective product next after being required to do so by the government in order to protect consumer, the “forced” characteristic of the recall is considered by customers as the company is actually have no concerns on their safety and just following direction by government. By recalling involuntary, an organization’s reputation will be further damage (Laufer & Coombs, 2006). Moreover, earlier studies presented that involuntary recall (opportunistic recall) has important negative impact on the producer’s image, consumer loyalty, consumers’ post-recall brand attitude as well as consumer purchase intention (e.g., Souiden & Pons, 2009; Magno et al., 2010). Therefore, this research aims to validate the findings in prior studies, which point out that opportunistic recall has important influence on consumer response. Apart from that, this research also will look at the consumers’ perceptions on what they see as an opportunistic product recall. Therefore, the following hypothesis was formed:

H1c: Opportunistic recall has significant influence on customer purchase intention post-crisis.

4.1.5. Blame Attribution

Blame attribution is described as the process where evaluations are completed by individuals regarding the causality in response to observed, affect-based negative outcomes perceived by themselves or others (including social transgressions) as failures (Meier & Robinson, 2004; Harvey & Dasborough, 2006; Fast & Tiedens, 2010). In the context of consumer behavior, blame attribution is described as the process through which consumers spontaneously construct attributions of responsibility to harmful brand (Gupta, 2009; Regan et al., 2015).

In a product-harm crisis, when products are found to be hazardous and defective, the public interest and attention are suddenly creating destructive consequences for the business. For instance, financial losses, reduced consumer trust, legal issues, brand equity, decreases consumers’ willingness to buy recalled product alongside other future products marketed by the company, purchase the recalled product along with other products marketed by the organization in the future. Moreover, an organization in crisis that is found to be blameworthy in addition suffers from negative word of mouth, complain, anger, and reduced support by its customers. Furthermore, a corporation in crisis found to be guilty also grieves from destructive complaints, anger, and less support by their consumers. Shaver (1985) stated that the blame attribution will only occurs when one of the causal fundamentals that points to the circumstances that demands for the assessment of accountability is “human action” and that an thing is only assigned to blame when the thing is found to be accountable by the observer. Once the entity is found to accountable for ethically objectionable manners, the entity will be expected to held responsible and then punished. In other words, if the customers blame the organization in crisis, the customers are more likely to penalize it (Gupta, 2009). Therefore, the hypothesis below was developed:

H1d: Blame attribution has significant influence on customer purchase intention post-crisis

4.1.6. Perceived Responsibility of Organization in Crisis

Based on Coombs (1998), crisis responsibility can be defined as “the stratum to which the stakeholders attack the organization during the crisis”. The stakeholders tend to identify a responsible party to shoulder the blame and at the same time reducing the harm caused during a crisis. Generally, , the significance of crisis responsibility related with an organization is grounded on the price of criticism set to the business which shows that customers search for something to assign their criticism of the crisis. The reputational threat level faced by a company in crisis can be assessed through the level of crisis accountability engaged by the interested party, which can furthermore be interpreted as the fault value, placed on the company (Brown & Ki, 2013).

Bickerstaff et al. (2006) indicated that the opinion of accountability is grounded on whether the players or things are recognized as the contributors to the incidence. Consumers deem a business that takes its failure as causally accountable to the crisis events. Busby (2008) noted that business is seeming accountable by customers if it is supposed to be ‘complicit’ by things tangled in risks generation whose responsibility in some way that may contributes to the risks. Therefore, the following hypothesis was formed:

H1e: Perceived crisis responsibility has significant influence on customer purchase intention post-crisis.

4.1.7. Crisis Communication

Crisis communication is specified as the gathering, handling, and distribution of required information in order to write a situation of the crisis (Coombs, 2010). Fearn-Banks (2007) stated that crisis communication is the communication between the business and its public before, during, and after the destructive incidence whereby the conversation specifics plans and strategies which are intended to reduce punishment to the organization image. The meaning of crisis communication throughout a crisis can furthermore be pointed and identified as the distribution of info to the public by the affected business to transcribe the crisis situation during the incident (Coombs, 2010).

Coombs (2010) pointed out that communication is the principle of crisis management and that it is trigger through entire crisis management process. Public opinions of the business during and without the crisis is swayed by communication conclusions made by the business (Sapriel, 2003; Hale et al., 2005). Crisis communication is extremely vital particularly throughout the crisis as it has important effect on the crisis consequences. For instance, the value of reputational punishment of the company, number of injuries (Coombs, 2010). The under structure of crisis communication who include the interested party response management (Coombs, 2009) deals with the effort the crisis management squad does to produce replies to the public during crisis. In precise, it includes the message efforts through words and manner to effect the opinions of interested party of the crisis, the business in crisis as well as the business’s crisis response. If communicating on time to reply to a crisis or remaining silent, other parties will take the chance to arrange for the crisis facts and therefore own how the crisis will be seen by stakeholders (Coombs, 2010). One of the most used theories in crisis communication Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) developed by Coombs and Holladay (2002) is unique theories used in crisis communication and is broadly used. SCCT is not only concentrating on the result aimed at crisis communication, but also imbricate the surprise and behavioral intentions for instance, purchase intention and negative opinion from stakeholders. The vital rule for SCCT is crisis responsibility, which will in turn affect their behavioral and affective responses to that organization following a crisis.

Crisis communication and crisis management go hand in hand during a crisis as it was pointed out by Coombs (2010) that communication is the essence of crisis management and that it is critical throughout the entire crisis management process. Public perceptions of the organization during and after the crisis is influenced by communication decisions made by the organization (Sapriel, 2003; Hale et al., 2005). Crisis communication is highly essential especially during the crisis as it has significant influence on the crisis outcomes. For instance, the amount of reputational damage of the organization and number of injuries (Coombs, 2010). The basis of crisis communication is the stakeholder reaction management (Coombs, 2009) deals with the work the crisis management team does in responding to the public during a crisis. In specific, it involves the communication efforts through words and actions to influence the perceptions of stakeholder, the organizations actions, as well as the organization’s crisis response. Therefore, the hypothesis below was developed:

H2: Crisis communication has significant influence on customer purchase intention post-crisis.

In order to study the moderating effect of crisis communication on the relationship between the elements of crisis management and customer purchase intention post-crisis, the following hypotheses were developed:

H3a: Crisis management has significant influence on customer purchase intention post-crisis, moderated by crisis communication.

H3b: Time has significant influence on customer purchase intention post-crisis, moderated by crisis communication.

H3c: Responsible recall has significant influence on customer purchase intention post-crisis, moderated by crisis communication.

H3d: Opportunistic recall has significant influence on customer purchase intention post-crisis, moderated by crisis communication.

H3e: Blame attribution has significant influence on customer purchase intention post-crisis, moderated by crisis communication.

H3f: Perceived crisis responsibility has significant influence on customer purchase intention post-crisis, moderated by crisis communication;

Research Methods

A quantitative research will be conducted through online survey by gathering individual responses in Malaysia.Data collection will be carried out by asking the respondents to fill in the online structured questionnaire which was created in Google Forms. Convenience sampling method will be adopted. E-mails as well as social media platforms such as WhatsApp containing the link to the structured questionnaire were in addition utilized. The self-administrated structured questionnaire will beadapted from previous studies as the survey instrument. The structured questionnaire used in this research will consist of two main parts of which Part 1 collected the respondents’ demographic information though Part 2 will be subdivided into three sections. In Section A, the respondents’ views on the elements of crisis management (time, responsible product recall, opportunistic product recall, blame attribution, and perceived crisis responsibility). In Sections B and C, the respondents’ views on crisis communication and purchase intention post-crisis which will be collected respectively. The data of respondents who will be participated in this study will be analyzed using the structural equation model (PLS-SEM).

Findings

The crisis management plan and the communication strategies that have been developed should be tried and tested through simulations in numerous scenarios. The minute the crisis management and crisis communication strategies have been executed to deal with a crisis, business firms through their crisis management team should monitor the implementation of their crisis management and crisis communication strategies, and evaluate their effectiveness and improvise them to deal with future crises more effectively with well preparation strategies and implementation. These evaluations on crisis management and communication effectiveness can be taken action by analysing customer’s response for instance customer purchase intention, customer brand attitude and the business firms’ financial position on recall activities, stakeholders reaction to the recall, and positive communication to the public on action taken when the news break lose. Strategic decisions to avoid legal implications on health and safety issues and related consumer damages claims are crucial during and after the post crisis.

Conclusion

Empirical research should be conducted to apply the theoretical model developed in this paper. A suggestion for future research is to explore how elements of crisis management (time, responsible recall, opportunistic recall, blame attribution, and perceived responsibility) could influence consumer purchase intention towards cosmetic and healthcare products. This study will provide useful information for future research that it should focus on how a crisis can be prevented or redirected by recognizing signals or trends that may lead to a crisis such as studied variables in this research.Since the concept of crisis management and crisis communication is very important for organization, there is need to examine factors that affect consumer purchase intention after each crisis occured.An organization should prepare with operative and effective crisis management and crisis communication plans that can support their execution of crisis management.

References

- Arpan, L. M., & Pompper, D. (2003). Stormy weather: Testing “stealing thunder” as a crisis communication strategy to improve communication flow between organizations and journalists. Public Relations Review, 29(3), 291-308.

- Bickerstaff, K., Simmons, P., & Pidgeon, N. (2006). Situating local experience of risk: Peripherality, marginality and place identity in the UK foot and mouth disease crisis. Geoforum, 37(5), 844-858.

- Brown, K. A., & Ki, E. J. (2013). Developing a valid and reliable measure of organizational crisis responsibility. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 90(2), 363-384.

- Busby, J. (2008). Analysing complicity in risk. Risk Analysis, 28(6), 1571-1582.

- Carroll, C. E. (2016). The SAGE encyclopedia of corporate reputation. SAGE Publications.

- Cleeren, K. (2015). Using advertising and price to mitigate losses in a product-harm crisis. Business Horizons, 58(2), 157-162.

- Coombs, W. T. (1998). An analytic framework for crisis situations: Better responses from a better understanding of the situation. Journal of public relations research, 10(3), 177-191.

- Coombs, W. T. (2007). Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(3), 163-177.

- Coombs, W. T. (2009). Ctheminuteptualizing crisis communication. Handbook of risk and crisis communication, 99-118.

- Coombs, W. T. (2010). Parameters for crisis communication. The handbook of crisis communication, 17-53.

- Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (2002). Helping crisis managers protect reputational assets: Initial tests of the situational crisis communication theory. Management Communication Quarterly, 16(2), 165-186.

- Dawar, N., & Lei, J. (2009). Brand crises: The roles of brand familiarity and crisis relevance in determining the impact on brand evaluations. Journal of Business Research, 62(4), 509-516.

- Dawar, N., & Pillutla, M. M. (2000). Impact of product-harm crises on brand equity: The moderating role of customer expectations. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(2), 215–226.

- Dilenschneider, R. L. (2000). The corporate communications bible: Everything you need to know to become a public relations expert. Beverly Hills: New Millennium.

- Dodds, W. B., Monroe, K. B., & Grewal, D. (1991). Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers' product evaluations. Journal of Marketing Research, 307-319.

- Fast, N. J., & Tiedens, L. Z. (2010). Blame contagion: The automatic transmission of selfserving attributions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(1), 97-106.

- Fearn-Banks, K. (2007). Crisis communications: A casebook approach (3rd ed.). New York, New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Gupta, S. (2009). How do customers judge celebrities' irresponsible behavior? An attribution theory perspective. The Journal of Applied Business and Economics, 10(3), 1.

- Hale, J. E., Dulek, R. E., & Hale, D. P. (2005). Crisis response communication challenges: Building theory from qualitative data. The Journal of Business Communication, 42(2), 112-134.

- Harvey, P., & Dasborough, M. T. (2006). Consequences of employee attributions in the workplace: The role of emotional intelligence. Psicothema, 18, 145-151.

- Hora M., Bapuji, H., & Roth, A.V. (2011). Safety hazard and time to recall: the role of recall strategy, product defect type, and supply chain player in the U.S. toy industry. Journal of Operations Management, 29, 766-777.

- Johnson-hall, T. (2012). Essays on product recall strategies and effectiveness in the FDA-regulated food sector (All dissertations). Retrieved from http://tigerprints.clemson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi? article=1996&context=all_dissertations

- Jolly, D. W., & Mowen, J. C. (1985). Product recall communications: The effects of source, media, and social responsibility information. Advances in Customer Research, 12, 471-475.

- Klein, J., & Dawar, N. (2004). Corporate social responsibility and customers’ attributions and brand evaluations in a product-harm crisis. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 21, 203–217.

- Laufer, D., Silver, D.H., & Meyer, T. (2005). Exploring differences between older and younger customers in attributions of blame for product harm crises. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 1.

- Laufer, D., & Coombs, W. T. (2006). How should an organization respond to a product harm crisis? The role of corporate reputation and customer-based cues. Business Horizons, 49(5), 379-385.

- Lockwood, N. R. (2005). Crisis Management in Today's Business Environment. USA: Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM).

- Magno, F., Cassia, F., & Marino, A. (2010). Exploring customers’ reaction to product recall messages: the role of responsibility, opportunism and brand reputation. In Proceedings of the 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics (pp. 15-16).

- Magno, F. (2012). Managing product recalls: The effects of time, responsible vs. opportunistic recall management and blame on customers’ attitudes. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 58, 1309–1315.

- Meier, B. P., & Robinson, M. D. (2004). Does quick to blame mean quick to anger? the role of agreeableness in dissociating blame and anger. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(7), 856-867. doi:

- Mitroff, I. I., & Alpaslan, C. M. (2014). Why people and organizations break down. The crisis-prone society: A brief guide to managing the beliefs that drive risk in business. New York: Palgrave Pivot.

- Mowen, J. C. (1980). Further information on customer perceptions of product recalls. Advances in Customer Research, 7(1), 519-523.

- PROCON. (2014) Recall Calling. Retrieved from https://sistemas.procon.sp.gov.br/recall.

- RAPEX (2016). Keeping European customers safe. 2015 annual report on the operation of the rapid alert system for non-food dangerous products. Luxembourg: European Commission. Directorate-General for Health & Customers.

- Regan, Á. Marcu, A., Shan, L. C., Wall, P., Barnett, J., & McConnon, Á. (2015). Ctheminuteptualising responsibility in the aftermath of the horsemeat adulteration incident: an online research with Irish and UK customers. Health, Risk & Society, 17(2), 149-167.

- Regester, M. (1989). Crisis Management. Random House Business Books.

- Roth, A. V., Tsay, A. A., Pullman, M. E., & Gray, J. V. (2008). Unraveling the food supply chain: strategic insights from China and 2007 recalls. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 44(1), 22-39.

- Sapriel, C. (2003). Effective crisis management: Tools and best practice for the new millennium. Journal of Communication Management, 7(4), 348-355.

- Schiffman, L. G., & Kanuk, L. L. (2000). Customer behavior, 7th. NY: Prentice Hall.

- Shaver, K. G. (1985). The attribution of blame: Causality, responsibility, and blameworthiness. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

- Shrivastava, P., & Siomkos, G. (1989). Disaster containment strategies. Journal of Business Strategy, 10(5), 26-30.

- Siomkos, G. (1989). Managing product-harm crises. Industrial Crisis Quarterly, 3(1), 41-60.

- Siomkos, G. J., & Kurzbard, G. (1994). Product harm crisis at the crossroads: monitoring recovery of replacement products. Industrial Crisis Quarterly, 6, 279–294.

- Souiden, N., & Pons, F. (2009). Product recall crisis management: the impact on manufacturer's image, customer loyalty and purchase intention. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 18(2), 106-114.

- Standop, D. (2006) Product recall versus business as usual: A preliminary analysis of decision-making in potential product-related crises. Paper presented at the 99th EAAE Seminar ‘Trust and Risk in Business Networks’, 8 – 10 February. Bonn, Germany.

- Stafford, G., Yu, L., & Armoo, A. K. (2002). Crisis management and recovery. How Washington, D.C., hotels responded to terrorism. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 43(5), 27-40. DOI:

- Vassilikopoulou, A., Lepetsos, A., Siomkos, G., & Chatzipanagiotou, K. (2009). The importance of factors influencing product-harm crisis management across different crisis extent levels: A conjoint analysis. Journal of Targeting, Measurement & Analysis for Marketing, 17(1), 65–74.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

02 August 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-064-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

65

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-749

Subjects

Business, innovation, sustainability, environment, green business, environmental issues

Cite this article as:

Ariffin, S. K., Ali, N. N. K., & Kamsan, S. N. A. (2019). The Influence of Crisis Management on Customer Purchase Intention. In C. Tze Haw, C. Richardson, & F. Johara (Eds.), Business Sustainability and Innovation, vol 65. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 216-226). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.08.22